Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis – a stepwise therapeutic approach

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20465

Nils C.

Nuessle, Esther

Vögelin, Stefanie

Hirsiger

Department of Hand and Peripheral Nerve Surgery, Inselspital University Hospital Bern, Switzerland

Summary

Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometarcarpal joint, also called rhizarthrosis, is a common finding in the second half of life. It has a higher prevalence in females and is of growing importance in ageing societies. A variety of conservative and surgical treatment options are known, including conservative treatment up to joint replacement. Without treatment, rhizarthrosis can lead to disabling pain and loss of hand function. The goal of this overview of treatment options is to present a stepwise approach that can be initiated by any physician.

Treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis should be started early with conservative measures such as splinting and physical therapy, which can be supplemented by oral and topical analgesics and local infiltrations subsequently. If all of these interventions do not provide sufficient relief, referral to a hand surgeon should be considered.

Surgical strategies vary from arthroscopic debridement over trapeziectomy, with or without tendon interposition and ligament reconstruction, to interposition implants and total joint replacements. The planned intervention should be based on clinical and subjective functional limitations and associated degenerative changes, as well as the patient’s expectations and needs.

The goal of this paper is to develop a treatment algorithm, leading to higher levels of patient functionality and satisfaction. Below we discuss the current literature and point out key treatment options used in our department.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis of the trapeziometarcarpal joint (TMO) is a common disease, especially in postmenopausal women [1, 2]. Radiological prevalence ranges from 13.4% above 70 years of age up to 35.8% above 55 years [3]. However, radiographic findings do not always correlate with clinical symptoms [4]. The prevalence of symptomatic TMO is notably lower than radiological changes, which are often incidental [5]. Symptomatic TMO has been found to peak at 5.3% in women aged 70–74 and at 1.7% in men aged 80–84 [6]. On the other hand, there is often no or little evidence of TMO on conventional radiographs in early stages, whereas functional limitations and pain can be very prominent [5]. Symptoms of TMO usually include pain in the trapeziometarcarpal (TMC) joint, reduced hand strength and decreased mobility of the thumb [7]. Pain can vary from episodic to pain related to a specific activity, sometimes accompanied by a background ache [7, 8]. Grasping and pinching is often limited [9]. As the thumb is needed for countless daily activities and represents approximately 40% of overall hand function, limitation of its function can be very disabling [9–11]. Known risk factors include obesity [5], heavy manual labour [12], female gender and hormonal changes, such as menopause [1]. Trauma, rheumatoid arthritis and hyperlaxity diseases (Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos) are risk factors for secondary osteoarthritis of the TMC joint [13, 14]. Because of our ageing societies, TMO is a growing medical challenge and economic burden [15]. Patients who are referred to our hand surgical consultation are mostly aware of their diagnosis, but have not yet received the full array of conservative treatments and often hesitate to consider surgical treatment. This review aims to give an overview of current and evidence-based treatment options and to formulate a stepwise approach for optimal patient care.

Imaging and classification

Conventional radiographs

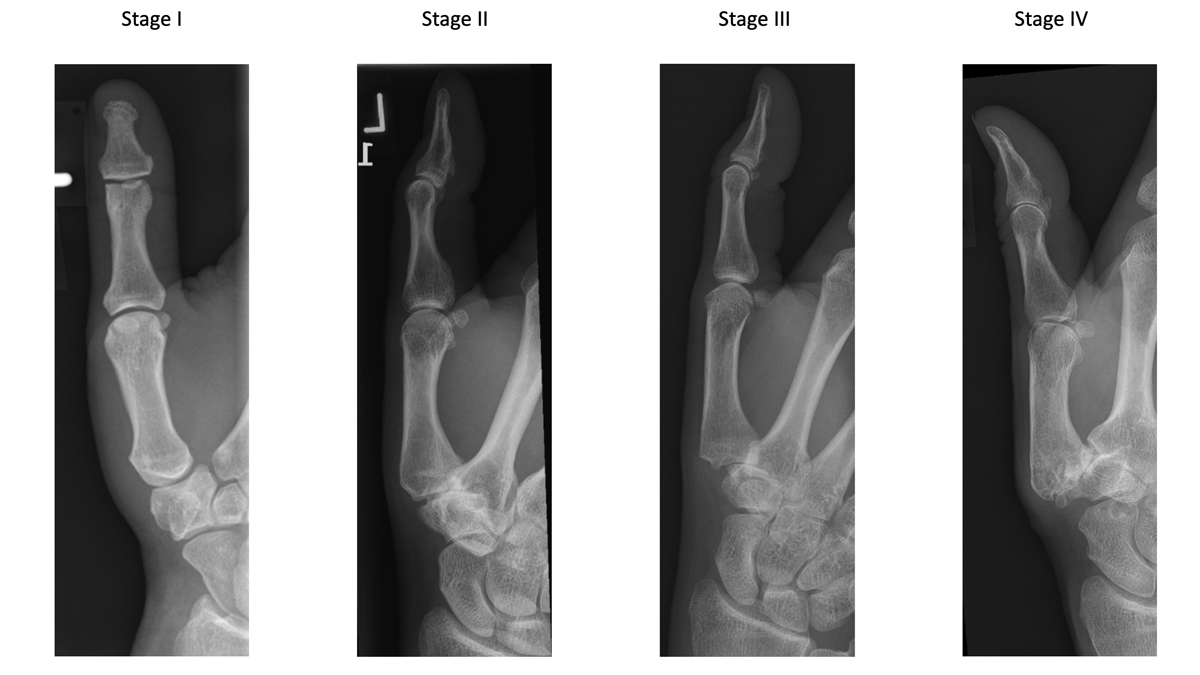

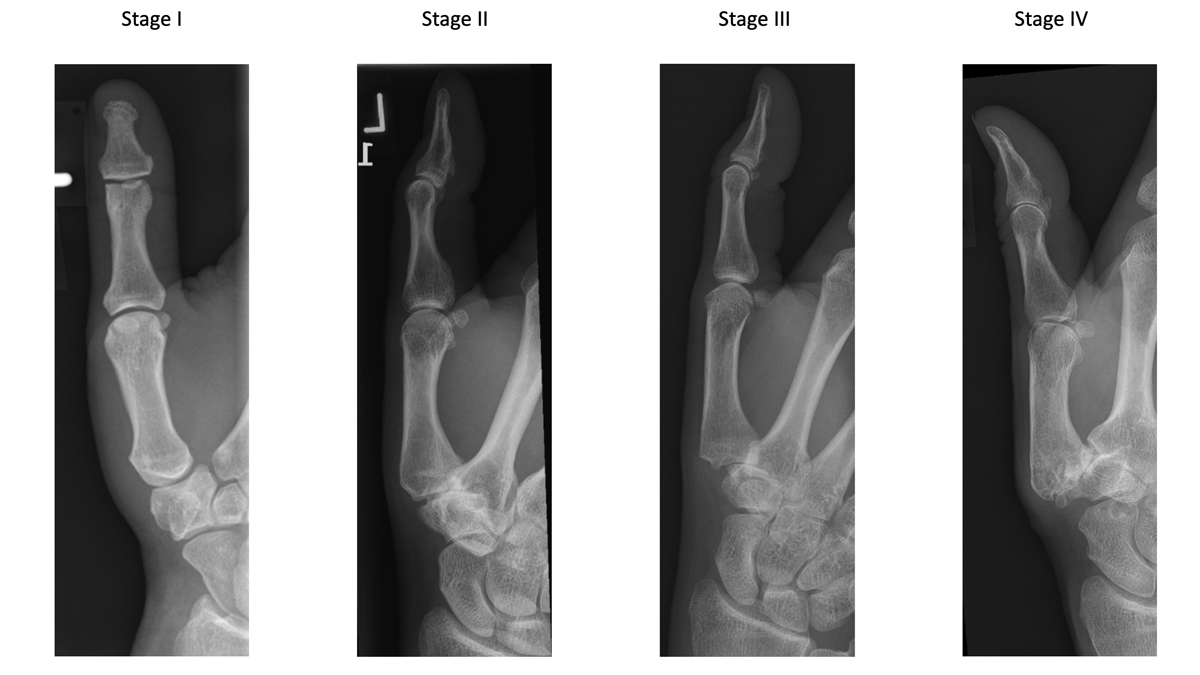

In 1987, Eaton and Littler proposed a radiological classification of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis, which is still the most widely used for staging. This classification system consists of four different stages (fig. 1) [16, 17]. Even though other imaging techniques and classification systems exist, X-rays of the thumb in two planes remain the gold standard and should be ordered early in suspected TMO [16, 17]. It is, however, important to evaluate the neighbouring joints such as the scaphotrapezial and scaphotrapezoidal (STT) joints for treatment.

Figure 1 Eaton/Littler classification of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis.

Stage I: slight widening of the joint space and normal contours.

Stage II: slight narrowing of the TMC and sclerosis, osteophytes <2mm, up to 1/3 subluxation of the joint

Stage III: marked joint space narrowing, osteophytes >2mm, >1/3 subluxation

Stage IV: Pantrapezial arthritis, major subluxation, cystic and sclerotic subchondral bone changes, significant erosion of the scaphotrapezial joint.

Additional imaging

Multilayer imaging can help to evaluate the trapeziometacarpal joint and the neighbouring joints in more detail. To evaluate bone stock and cartilage surfaces, and especially if planning prosthetic implants, computed tomography (CT) enhanced by intra-articular contrast injection can be useful [18]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows ligament and soft tissue evaluation. Recent developments of specific sequences can quantitatively analyse cartilage or define alterations in its composition [19]. Single-photon emission computed tomography combined with conventional CT (SPECT/CT) can be used to discriminate between pain arising from the TMC or the STT joint [20]. In patients with persistent postoperative pain SPECT is a good adjunct, as other forms of imaging can be difficult to evaluate owing to residual changes from the intervention [21]. Arthroscopic evaluation may allow earlier and more detailed evaluation of degenerative changes [22].

The treatment ladder

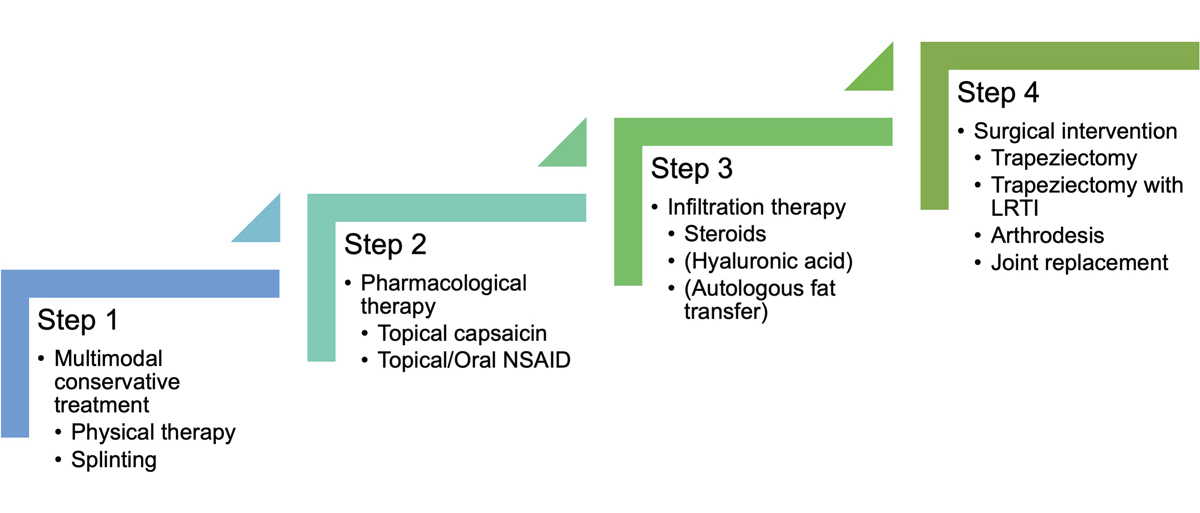

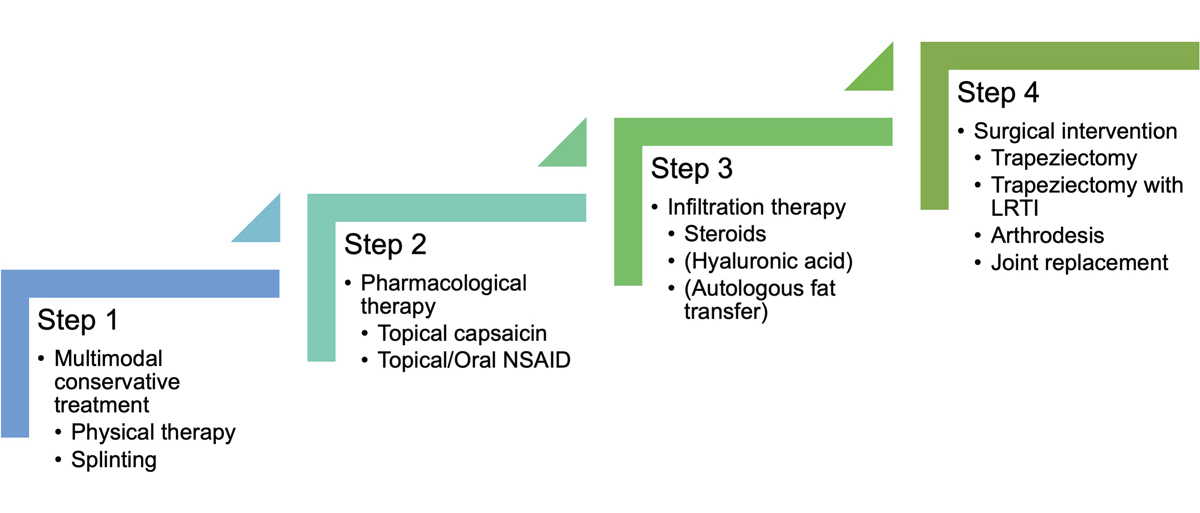

Treatment of TMO should not only be based on the radiological classification, but also focus on the patient’s symptoms, subjective loss of function and the evolution over time. Conservative options are at the bottom and ultimately surgery is the last step of the treatment ladder (fig. 2). The treatment ladder is based on current literature, as well as experience in our centre.

Figure 2 Treatment ladder for basal thumb osteoarthritis. A structured approach for all caregivers recommended by the department of hand surgery at Inselspital Bern, Switzerland. Different steps should be combined to ensure optimal treatment. If results are unsatisfactory for the patient, the treatment can be escalated to the next step.

Step I: Multimodal conservative treatment

In every stage of TMO, conservative treatment is the first step of the treatment ladder. All therapeutic modalities described below should be used in combination to optimise the treatment effect.

Splinting

In a recent meta-analysis, splinting caused a moderate to large reduction in pain in the medium term (3–12 months) and an improvement of function, and can avoid surgical treatment in some patients [23, 24]

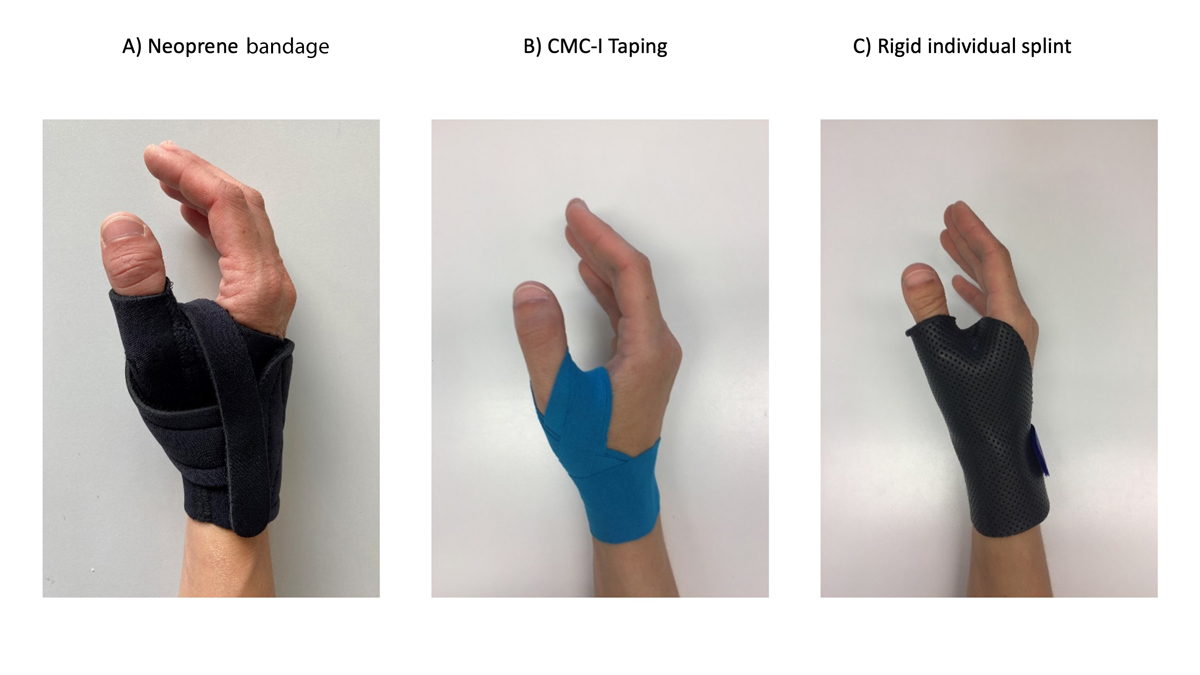

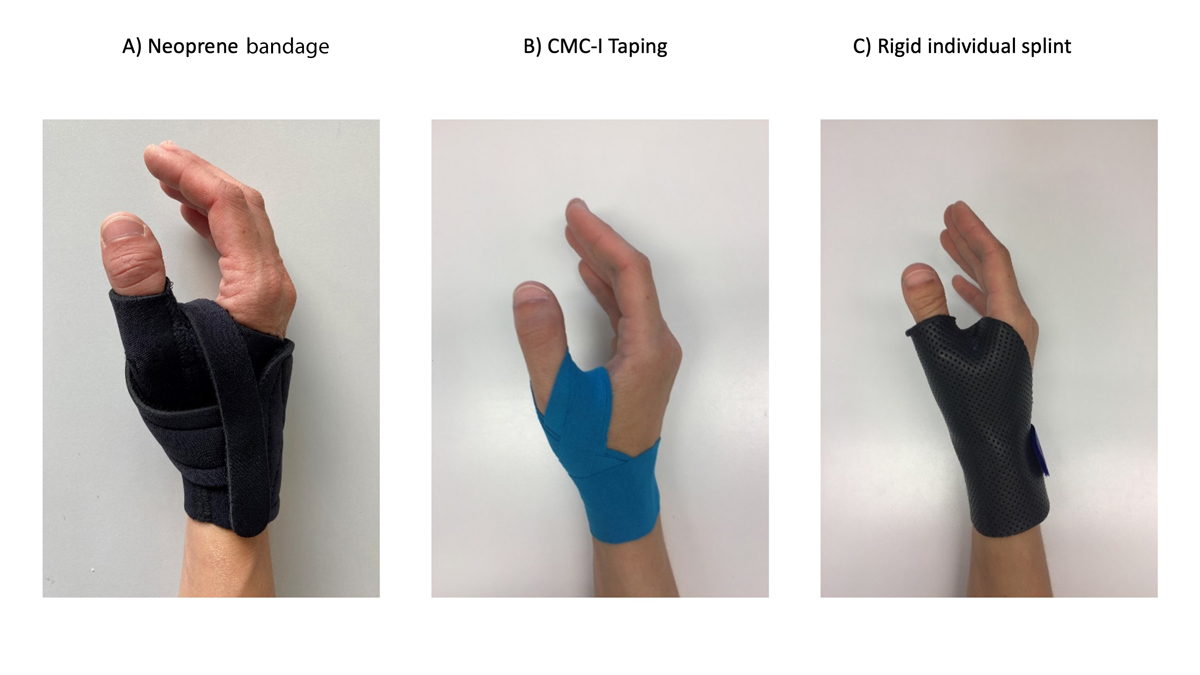

In our experience, neoprene bandages provide a high level of comfort for the patients with low risk of developing pressure points, at low cost. Additionally, they serve as an insulation layer, which may help to reduce cold-related worsening of symptoms (fig. 3a). For some patients, taping may present a good alternative (fig. 3b) [25]. For those more comfortable with a rigid support, a thermomoulded splint can be an option (fig. 3c).

Figure 3 Different splints of the TMC joint. The right splint has to be chosen according to the patient’s needs and demands. Neoprene bandages (a) provide a high level of comfort and serve as insulation layer. Taping (b) presents a good alternative, especially for those needing to wear gloves at work (e.g., healthcare professionals). Rigid individual splints (c) provide the highest level of stability.

Physical therapy

Physical therapy by specialised hand therapists leads to a significant improvement in pain and hand function [26]. Specific hand exercises help to increase grip strength and function, reduce pain and improve the range of movement of the thumb [27]. Some investigators focus primarily on increasing the range of movement and strengthening intrinsic and extrinsic muscles by providing a set of exercises that are based on biomechanical findings in cadaver studies [28]. Others prefer the so-called dynamic stability modelled approach, including a variety of hand exercises that focus on restoration of the thumb web space, re-education of thumb muscles, joint mobilisation and muscle strengthening, which has been able to show significant reduction in pain and disability [29].

We therefore recommend initiating physical therapy, together with splinting, as one of the first steps in treating TMO [30].

Step 2: Pharmacological therapy

The American College of Rheumatology in 2012 and the European League against Rheumatism recommended the use of one or more of the following drugs for patients suffering from hand osteoarthritis [31, 32]:

- Topical capsaicin

- Topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Oral NSAIDs, including cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX2)-selective inhibitors

- Oral chondroitin sulphate

In patients older than 75 years, topical use of NSAIDs is preferred, as side effects might outweigh the benefits of systemic application, especially when used over a longer period of time [31–33]. There is no evidence on superiority of one specific anti-inflammatory treatment over another in TMO [31, 32]. In addition, topical capsaicin has been described as an option to reduce tenderness and pain [34, 35].

Oral chondroitin sulphate has shown effectiveness in relieving symptoms of hand osteoarthritis [36]. As side effects are rare and benign, we recommend its use.

Paracetamol is regularly prescribed for patients suffering from hand osteoarthritis with contraindications for NSAID use [31]. However, in three small trials, paracetamol showed no superiority over placebo or an active comparator [31, 37–39].

Therefore, as an add-on therapy to step 1, we recommend analgesics for short-term use, if applied orally. If all conservative treatments fail, treatment can be escalated to more invasive approaches.

Step 3: Infiltration therapy

Corticosteroid injections into the TMC joint can provide short-term benefits, with pain relief and improved function [40]. Unfortunately, the effect usually does not last longer than 1–3 months [40–42]. Nevertheless, in early stages of TMO or when inflammation is predominant corticosteroids infiltration, in combination with splinting, can provide long-term pain relief [43]. It remains unclear whether the volume injected into the joint or specific anti-inflammatory effects are responsible for pain reduction, as some studies have revealed that saline injections can provide similar results [9, 42].

Hyaluronic acid or dextrose injections present alternatives for injection therapy [44] and autologous fat transfer (stem cells) was suggested as an interesting alternative [45]. Nevertheless, only steroid injections are reimbursed by insurance companies in Switzerland. Complications and morbidity of injections are generally low. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, no adverse effects, such as intra-articular infections, were found in the studies included [44]. On the other hand, the evidence for long-term benefits was considered low, so that injections remain a topic of discussion [44].

If pain relief is provided effectively by the first steroid injection, we recommend up to three injections with a delay of 3 months before escalating to a surgical intervention.

Step 4: Surgical interventions

Several surgical interventions exist for the treatment of TMO, but none has been shown to be ultimately superior [46]. We will shortly describe the different options and their indications hereafter.

Trapeziectomy with or without ligament reconstruction and interposition

Resection arthroplasty consists of surgical removal of the trapezium bone and can be combined with ligament reconstruction and interposition (LRTI).

The latter adds suspension with a tendon strip in order to support the first metacarpal bone, as well as filling the trapezial space with the partially resected local tendon (fig. 4) [47]. Both interventions show equal long-term outcomes, nevertheless simple trapeziectomy is a shorter procedure with slightly lower complication rates [48–51]. Nevertheless, most hand surgeons prefer LRTI to simple trapeziectomy [52] and it thus represents the most common surgical therapy for patients suffering from advanced stages of TMO [6]. A possible explanation could be that the ligament reconstruction allows initial suspension and early functional rehabilitation. Ligament reconstruction and interposition using artificial material or allografts have fallen out of favour due to significantly higher complication rates [53].

Shortcomings of both techniques are the risk of subsidence of the first ray and decreased strength and mobility [54]. Although studies show no correlation between success of LRTI and radiologic subsidence [55–57], a conflict between the scaphoid and the base of the metacarpal I can be a reason for persistence or recurrent pain. Especially in advanced TMO, when the scaphotrapeziotrapezoidal (STT) joint is involved, partial trapezial excision has been shown to exacerbate pre-existing positional abnormalities and degenerative changes of the carpus [52, 58]. Other options should be considered in these situations.

Joint replacement surgery

Alternatives consist of a wide variety of interpositional prosthetic implants, whose use has been increasing in the last decades [59]. In the early days, loosening presented the main complication of the different subtypes, with rates ranging from 3% up to 53% [60–62]. Most prosthetic implants changed continuously over time, so that long-term outcomes mainly exist for models not being used anymore because of high complication rates. On the other hand, some studies report better postoperative pinch strength, greater reduction in metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint hyperextension and faster recovery for patients treated with a prosthesis [63–65]. Non-cemented prostheses provide better results in mid-term follow-up [66, 67], high rates of patient satisfaction and 71–92% survival rates in a 10-year follow-up [68, 69]. There is a lack of prospective studies directly comparing trapeziectomy with the different prostheses [59], but at present overall prosthetic implants seem to have a higher complication rate and inferior long-term outcomes compared with resection arthroplasty [69, 70]. There are several other treatment options, but for an overview we focus on the procedures and techniques used in the department of hand surgery at Inselspital (Bern, Switzerland). Thus, one model representative of a total joint replacement prosthesis (Touch®), one surface replacement implant (Pyrocardan®) and the surgical technique of arthrodesis are described below.

Total joint replacement prosthesis

The Touch® prosthesis (KeriMedical, Geneva, Switzerland) has been introduced onto the market as a dual mobility trapeziometarcarpal prosthesis. A first case series of 132 patients showed a reduction of luxations and a longer lifespan compared with older prosthesis [71]. Because of faster rehabilitation and preservation of length in the first ray, this possibility can be considered especially for younger patients and if fine motor skills are needed. However, as long-term data for this prosthesis are not yet available, the pros and cons should be discussed in detail with the patient. At this point, there is a need for high-quality randomised studies to investigate whether it is able to deliver superior long-term results [72].

Spacer

Pyrocarbon has a module of elasticity similar to that of cortical bone and is therefore well suited for interposition arthroplasties [73]. There are several implant models for different joints. The Pyrocardan® spacer is a hyperbolic paraboloid disk, which is inserted into the joint after partial resection of the first metacarpal and the trapezium bone (fig. 5). Five-year survival rates of 90% were reported [74]. In several studies, the Pyrocardan® spacer had similar outcomes to conventional arthroplasties, but shorter postoperative rehabilitation until relief of symptoms [75, 76]. Revision rates in several studies vary from 3.2% after 60 months of follow up to 25% after 26 months [75, 77].

The main benefit of using an interposition arthroplasty is the maintenance of length of the first ray. Furthermore, it can easily be revised by a trapeziectomy with or without LRTI in the case of failure [78, 79]. Pyrocardan® implants can also be used as a double arthroplasty in the TMC and STT joints in patients with stage IV osteoarthritis, or as an interposition spacer after failed trapeziectomy with subsidence [80]. As for the other prosthetic implants, no prospective long-term data proving its superiority to simple trapeziectomy are available and thus the potential advantages have to be outweighed with the complication rate and higher cost.

Arthrodesis

Lastly, arthrodesis may be a primary or a salvage option for TMO [81]. Arthrodesis as a treatment option for TMO is reserved for a limited subgroup of patients, as it fixes the position of the thumb in physiological antepulsion. However, the length of the first ray is better preserved with more force due to the proximal stability on the cost of motion. Arthrodesis has been shown to have relatively high rates of non-union, especially with earlier bone fixation techniques and it may lead to further progression of STT arthrosis [82–84]. In one study, an increased grip strength following arthrodesis as compared with trapeziectomy with LRTI has been described [50]. In our opinion, arthrodesis is therefore only indicated in exceptional cases such as young manual workers or complex revision cases.

Overview

In our ageing society, osteoarthrosis of the trapeziometacarpal joint represents a common disease of growing importance. The challenge to enable good access to optimised treatment options requires a stepwise approach. The growing number of patients suffering from TMO demands standardised treatment schemes applicable not only by hand surgeons.

Following clinical examination and conventional x-rays, to ensure the right diagnosis, we therefore recommend the subsequent stepwise approach for all caregivers involved in the patient’s care:

Step 1: Multimodal conservative treatment, including education, physical therapy and splinting. Specific hand therapy may apply physical anti-inflammatory and analgesic treatments, as well as instruct correct use of the weakened thumb.

Step 2: Pharmacological therapy, which involves chondroitin sulphate, topical capsaicin, short-term treatment with oral NSAIDs. For all pharmacological treatments, the individual patient’s risk factors need to be respected to ensure the right risk-benefit-ratio. In addition, oral chondroitin sulphate has been investigated and might present an alternative in the future.

Step 3: Infiltration therapy of the TMC joint, using steroids, hyaluronic acid, dextrose or saline showed contradictory results in the latest studies. They might offer a treatment option, as the rate of adverse effects is very low. Also, infiltration therapy showed a potential to postpone surgery. We recommend only cortisone infiltration, as it is the only product accepted by insurance companies.

Step 4: Surgical interventions are indicated, if all conservative treatment options fail and symptoms lead to unacceptably diminished function for the patient.

Many different surgical options exist. Currently, simple trapeziectomy or trapeziectomy with LRTI present comparable options with no significant differences in long-term results. Newer therapies, such as total joint or surface replacement using implants were able to show faster rehabilitation time, but often less convincing long-term results. For many newer types of prosthesis, long-term follow-up data are still lacking. Therefore, they should only be discussed with caution in young patients with high demands. In the case of an unfavourable outcome, secondary trapeziectomy presents a surgical option.

Steps 1–3 can easily be taken by general practitioners, rheumatologists, orthopaedic surgeons and other colleagues caring for TMO patients and do not require immediate consultation of a hand surgeon. These steps have been shown to avoid or postpone more invasive treatments, while reducing the patient’s symptoms.

If these measures fail over a period of at least 3 months, we recommend discussing referral to a hand surgeon to evaluate the patient’s needs and will for surgery.

This review of current state-of-the-art therapies aims to emphasise that coordinated and combined use of different treatment options has a higher chance to lead to long-term patient satisfaction and might postpone or prevent surgery.

References

1

Armstrong

AL

,

Hunter

JB

,

Davis

TR

. The prevalence of degenerative arthritis of the base of the thumb in post-menopausal women. J Hand Surg [Br]. 1994;19(3):340–1. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/0266-7681(94)90085-X

2

Swigart

CR

,

Eaton

RG

,

Glickel

SZ

,

Johnson

C

. Splinting in the treatment of arthritis of the first carpometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(1):86–91. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1053/jhsu.1999.jhsu24a0086

3National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance. Osteoarthritis: Care and Management in Adults. London: NICE; 2014.

4

Botha-Scheepers

S

,

Riyazi

N

,

Watt

I

,

Rosendaal

FR

,

Slagboom

E

,

Bellamy

N

, et al.

Progression of hand osteoarthritis over 2 years: a clinical and radiological follow-up study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68(8):1260–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2008.087981

5

Dahaghin

S

,

Bierma-Zeinstra

SM

,

Ginai

AZ

,

Pols

HA

,

Hazes

JM

,

Koes

BW

. Prevalence and pattern of radiographic hand osteoarthritis and association with pain and disability (the Rotterdam study). Ann Rheum Dis. 2005;64(5):682–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.2004.023564

6

Wolf

JM

,

Delaronde

S

. Current trends in nonoperative and operative treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a survey of US hand surgeons. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(1):77–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.10.010

7

Wilkens

SC

,

Meghpara

MM

,

Ring

D

,

Coert

JH

,

Jupiter

JB

,

Chen

NC

. Trapeziometacarpal Arthrosis. JBJS Rev. 2019;7(1):e8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.RVW.18.00020

8

McQuillan

TJ

,

Kenney

D

,

Crisco

JJ

,

Weiss

AP

,

Ladd

AL

. Weaker Functional Pinch Strength Is Associated With Early Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(2):557–61. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-015-4599-9

9

Hamasaki

T

,

Laprise

S

,

Harris

PG

,

Bureau

NJ

,

Gaudreault

N

,

Ziegler

D

, et al.

Efficacy of non-surgical interventions for trapeziometacarpal (thumb base) osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(12):1719–35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.24084

10

Ladd

AL

,

Weiss

AP

,

Crisco

JJ

,

Hagert

E

,

Wolf

JM

,

Glickel

SZ

, et al.

The thumb carpometacarpal joint: anatomy, hormones, and biomechanics. Instr Course Lect. 2013;62:165–79.

11

Berger

AJ

,

Meals

RA

. Management of osteoarthrosis of the thumb joints. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(4):843–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.11.026

12

Jensen

JC

,

Sherson

D

. Work-related bilateral osteoarthritis of the first carpometacarpal joints. Occup Med (Lond). 2007;57(6):456–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqm029

13

Wolf

JM

,

Schreier

S

,

Tomsick

S

,

Williams

A

,

Petersen

B

. Radiographic laxity of the trapeziometacarpal joint is correlated with generalized joint hypermobility. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(7):1165–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.03.017

14

Jónsson

H

,

Valtýsdóttir

ST

,

Kjartansson

O

,

Brekkan

A

. Hypermobility associated with osteoarthritis of the thumb base: a clinical and radiological subset of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996;55(8):540–3. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/ard.55.8.540

15

Hamasaki

T

,

Lalonde

L

,

Harris

P

,

Bureau

NJ

,

Gaudreault

N

,

Ziegler

D

, et al.

Efficacy of treatments and pain management for trapeziometacarpal (thumb base) osteoarthritis: protocol for a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2015;5(10):e008904. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008904

16

Eaton

RG

,

Glickel

SZ

. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Staging as a rationale for treatment. Hand Clin. 1987;3(4):455–71.

17

Kennedy

CD

,

Manske

MC

,

Huang

JI

. Classifications in Brief: The Eaton-Littler Classification of Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint Arthrosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(12):2729–33. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4864-6

18

Cernohorsky

P

,

Strackee

SD

,

Streekstra

GJ

,

van den Wijngaard

JP

,

Spaan

JAE

,

Siebes

M

, et al.

Computed Tomography-Mediated Registration of Trapeziometacarpal Articular Cartilage Using Intraarticular Optical Coherence Tomography and Cryomicrotome Imaging: A Cadaver Study. Cartilage. 2019:1947603519860247. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1947603519860247

19

Hayashi

D

,

Roemer

FW

,

Guermazi

A

. Imaging of osteoarthritis-recent research developments and future perspective. Br J Radiol. 2018;91(1085):20170349. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1259/bjr.20170349

20

van Rijn

SF

,

de Vries

MR

,

Kraan

GA

. The use of single photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography to differentiate between pain arising from trapeziometacarpal joint and scaphotrapeziotrapezoid joint osteoarthritis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2016;41(7):776–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193415606070

21

Strobel

K

,

van der Bruggen

W

,

Hug

U

,

Gnanasegaran

G

,

Kampen

WU

,

Kuwert

T

, et al.

SPECT/CT in Postoperative Hand and Wrist Pain. Semin Nucl Med. 2018;48(5):396–409. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.semnuclmed.2018.05.001

22

Badia

A

. Trapeziometacarpal arthroscopy: a classification and treatment algorithm. Hand Clin. 2006;22(2):153–63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hcl.2006.02.006

23

Buhler

M

,

Chapple

CM

,

Stebbings

S

,

Sangelaji

B

,

Baxter

GD

. Effectiveness of splinting for pain and function in people with thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2019;27(4):547–59. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2018.09.012

24

Valdes

K

,

Marik

T

. A systematic review of conservative interventions for osteoarthritis of the hand. J Hand Ther. 2010;23(4):334–50, quiz 351. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2010.05.001

25

Villafañe

JH

,

Langford

D

,

Alguacil-Diego

IM

,

Fernández-Carnero

J

. Management of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis pain and dysfunction using mobilization with movement technique in combination with kinesiology tape: a case report. J Chiropr Med. 2013;12(2):79–86. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2013.06.001

26

Ahern

M

,

Skyllas

J

,

Wajon

A

,

Hush

J

. The effectiveness of physical therapies for patients with base of thumb osteoarthritis: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2018;35:46–54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2018.02.005

27

Spaans

AJ

,

van Minnen

LP

,

Kon

M

,

Schuurman

AH

,

Schreuders

AR

,

Vermeulen

GM

. Conservative treatment of thumb base osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(1):16–21.e6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.08.047

28

Valdes

K

,

von der Heyde

R

. An exercise program for carpometacarpal osteoarthritis based on biomechanical principles. J Hand Ther. 2012;25(3):251–62, quiz 263. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2012.03.008

29

O’Brien

VH

,

Giveans

MR

. Effects of a dynamic stability approach in conservative intervention of the carpometacarpal joint of the thumb: a retrospective study. J Hand Ther. 2013;26(1):44–51, quiz 52. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jht.2012.10.005

30

Østerås

N

,

Kjeken

I

,

Smedslund

G

,

Moe

RH

,

Slatkowsky-Christensen

B

,

Uhlig

T

, et al.

Exercise for Hand Osteoarthritis: A Cochrane Systematic Review. J Rheumatol. 2017;44(12):1850–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3899/jrheum.170424

31

Kloppenburg

M

,

Kroon

FP

,

Blanco

FJ

,

Doherty

M

,

Dziedzic

KS

,

Greibrokk

E

, et al.

2018 update of the EULAR recommendations for the management of hand osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2019;78(1):16–24. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/annrheumdis-2018-213826

32

Hochberg

MC

,

Altman

RD

,

April

KT

,

Benkhalti

M

,

Guyatt

G

,

McGowan

J

, et al.; American College of Rheumatology. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012;64(4):465–74. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/acr.21596

33

Pelletier

JP

,

Martel-Pelletier

J

,

Rannou

F

,

Cooper

C

. Efficacy and safety of oral NSAIDs and analgesics in the management of osteoarthritis: Evidence from real-life setting trials and surveys. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4, Suppl):S22–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.11.009

34

McCarthy

GM

,

McCarty

DJ

. Effect of topical capsaicin in the therapy of painful osteoarthritis of the hands. J Rheumatol. 1992;19(4):604–7.

35

Laslett

LL

,

Jones

G

. Capsaicin for osteoarthritis pain. Prog Drug Res. 2014;68:277–91.

36

Gabay

C

,

Medinger-Sadowski

C

,

Gascon

D

,

Kolo

F

,

Finckh

A

. Symptomatic effects of chondroitin 4 and chondroitin 6 sulfate on hand osteoarthritis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial at a single center. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(11):3383–91. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/art.30574

37

Reginster

JY

,

Neuprez

A

,

Lecart

MP

,

Sarlet

N

,

Bruyere

O

. Role of glucosamine in the treatment for osteoarthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2012;32(10):2959–67. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-012-2416-2

38

Rovetta

GMP

. Dexketoprofen-trometamol in patients with osteoarthritis of the hands. Minerva Ortop Traumatol. 2001;52(1):27–30.

39

McKendry

RTC

,

Weisman

M

. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) versus acetaminophen (ACM) versus placebo (PL) in the treatment of nodal osteoarthritis (NOA) of the hands. J Rheumatol. 2001;28:1421.

40

Fowler

A

,

Swindells

MG

,

Burke

FD

. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections to manage trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis-a systematic review. Hand (N Y). 2015;10(4):583–92. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-015-9778-3

41

Swindells

MG

,

Logan

AJ

,

Armstrong

DJ

,

Chan

P

,

Burke

FD

,

Lindau

TR

. The benefit of radiologically-guided steroid injections for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2010;92(8):680–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1308/003588410X12699663905078

42

Rocchi

L

,

Merolli

A

,

Giordani

L

,

Albensi

C

,

Foti

C

. Trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: a prospective trial on two widespread conservative therapies. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2018;7(4):603–10. doi:.https://doi.org/10.32098/mltj.04.2017.16

43

Day

CS

,

Gelberman

R

,

Patel

AA

,

Vogt

MT

,

Ditsios

K

,

Boyer

MI

. Basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb: a prospective trial of steroid injection and splinting. J Hand Surg Am. 2004;29(2):247–51. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2003.12.002

44

Riley

N

,

Vella-Baldacchino

M

,

Thurley

N

,

Hopewell

S

,

Carr

AJ

,

Dean

BJF

. Injection therapy for base of thumb osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e027507. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027507

45

Herold

C

,

Rennekampff

HO

,

Groddeck

R

,

Allert

S

. Autologous Fat Transfer for Thumb Carpometacarpal Joint Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(2):327–35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000003510

46

Baker

RHJ

,

Al-Shukri

J

,

Davis

TRC

. Evidence-Based Medicine: Thumb Basal Joint Arthritis. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139(1):256e–66e. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000002858

47

Klionsky

DJ

,

Abdelmohsen

K

,

Abe

A

,

Abedin

MJ

,

Abeliovich

H

,

Acevedo Arozena

A

, et al.

Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy. 2016;12(1):1–222. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356

48

Zafonte

B

,

Szabo

RM

. Evidence-based medicine in hand surgery: clinical applications and future direction. Hand Clin. 2014;30(3):269–83, v. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hcl.2014.04.005

49

Vermeulen

GM

,

Slijper

H

,

Feitz

R

,

Hovius

SE

,

Moojen

TM

,

Selles

RW

. Surgical management of primary thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):157–69. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2010.10.028

50

Raven

EE

,

Kerkhoffs

GM

,

Rutten

S

,

Marsman

AJ

,

Marti

RK

,

Albers

GH

. Long term results of surgical intervention for osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint : comparison of resection arthroplasty, trapeziectomy with tendon interposition and trapezio-metacarpal arthrodesis. Int Orthop. 2007;31(4):547–54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-006-0217-5

51

Huang

K

,

Hollevoet

N

,

Giddins

G

. Thumb carpometacarpal joint total arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2015;40(4):338–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193414563243

52

Yuan

BJ

,

Moran

SL

,

Tay

SC

,

Berger

RA

. Trapeziectomy and carpal collapse. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(2):219–27. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.11.007

53

Marks

M

,

Hensler

S

,

Wehrli

M

,

Scheibler

AG

,

Schindele

S

,

Herren

DB

. Trapeziectomy With Suspension-Interposition Arthroplasty for Thumb Carpometacarpal Osteoarthritis: A Randomized Controlled Trial Comparing the Use of Allograft Versus Flexor Carpi Radialis Tendon. J Hand Surg Am. 2017;42(12):978–86. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2017.07.023

54

Wajon

A

,

Vinycomb

T

,

Carr

E

,

Edmunds

I

,

Ada

L

. Surgery for thumb (trapeziometacarpal joint) osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(2):CD004631.

55

Yang

Y

,

Tien

HY

,

Kumar

KK

,

Chen

S

,

Li

Z

,

Tian

W

, et al.

Ligament reconstruction with tendon interposition arthroplasty for first carpometacarpal joint osteoarthritis. Chin Med J (Engl). 2014;127(22):3921–5.

56

Yang

SS

,

Weiland

AJ

. First metacarpal subsidence during pinch after ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition basal joint arthroplasty of the thumb. J Hand Surg Am. 1998;23(5):879–83. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0363-5023(98)80167-6

57

Gangopadhyay

S

,

McKenna

H

,

Burke

FD

,

Davis

TR

. Five- to 18-year follow-up for treatment of trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a prospective comparison of excision, tendon interposition, and ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(3):411–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.11.027

58

Tay

SC

,

Moran

SL

,

Shin

AY

,

Linscheid

RL

. The clinical implications of scaphotrapezium-trapezoidal arthritis with associated carpal instability. J Hand Surg Am. 2007;32(1):47–54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2006.10.021

59Ceruso M, Munz G, Carulli C, Virgili G, Viviani A, Hollevoet N, et al. Thumb TMC Joint Osteo-Arthritis. In: Giddins G, Leblebicioğlu G (eds). Evidence Based Data In Hand Surgery And Therapy. St Gallen: FESSH; 2017. pp 368–428

60

Wachtl

SW

,

Guggenheim

PR

,

Sennwald

GR

. Cemented and non-cemented replacements of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80-B(1):121–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.80B1.0800121

61

van Cappelle

HG

,

Elzenga

P

,

van Horn

JR

. Long-term results and loosening analysis of de la Caffinière replacements of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(3):476–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1053/jhsu.1999.0476

62

Giddins

G

. Thumb arthroplasties. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2012;37(7):603–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193412455988

63

Degeorge

B

,

Dagneaux

L

,

Andrin

J

,

Lazerges

C

,

Coulet

B

,

Chammas

M

. Do trapeziometacarpal prosthesis provide better metacarpophalangeal stability than trapeziectomy and ligamentoplasty?

Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2018;104(7):1095–100. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2018.07.008

64

Jager

T

,

Barbary

S

,

Dap

F

,

Dautel

G

. Analyse de la douleur postopératoire et des résultats fonctionnels précoces dans le traitement de la rhizarthrose. Étude prospective comparative de 74 patientes trapézectomie-interposition vs prothèse MAIA® [Evaluation of postoperative pain and early functional results in the treatment of carpometacarpal joint arthritis. Comparative prospective study of trapeziectomy vs. MAIA(®) prosthesis in 74 female patients]. Chir Main. 2013;32(2):55–62. Article in French. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.main.2013.02.004

65

Jurča

J

,

Němejc

M

,

Havlas

V

. [Surgical Treatment for Advanced Rhizarthrosis. Comparison of Results of the Burton-Pellegrini Technique and Trapeziometacarpal Joint Arthroplasty]. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2016;83(1):27–31. Article in Czech.

66

Vandenberghe

L

,

Degreef

I

,

Didden

K

,

Fiews

S

,

De Smet

L

. Long term outcome of trapeziectomy with ligament reconstruction/tendon interposition versus thumb basal joint prosthesis. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(8):839–43. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193412469010

67

Cebrian-Gomez

R

,

Lizaur-Utrilla

A

,

Sebastia-Forcada

E

,

Lopez-Prats

FA

. Outcomes of cementless joint prosthesis versus tendon interposition for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: a prospective study. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2019;44(2):151–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193418787151

68

Tchurukdichian

A

,

Guillier

D

,

Moris

V

,

See

LA

,

Macheboeuf

Y

. Results of 110 IVORY® prostheses for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45(5):458–64. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193419899843

69

Froschauer

SM

,

Holzbauer

M

,

Hager

D

,

Schnelzer

R

,

Kwasny

O

,

Duscher

D

. Elektra prosthesis versus resection-suspension arthroplasty for thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: a long-term cohort study. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2020;45(5):452–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1753193419873230

70

Froschauer

SM

,

Holzbauer

M

,

Schnelzer

RF

,

Behawy

M

,

Kwasny

O

,

Aitzetmüller

MM

, et al.

Total arthroplasty with Ivory® prosthesis versus resection-suspension arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study on 82 carpometacarpal-I osteoarthritis patients over 4 years. Eur J Med Res. 2020;25(1):13. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s40001-020-00411-8

71

Lussiez

B

,

Ledoux

P

,

Falaise

C

. Prothèse trapèze-métacarpienne à double mobilité: revue d’une série de 132 cas à plus de 1 an de recul [Dual-mobility trapezio-metacarpal prosthesis: Report of 132 first cases with a minimum follow-up of 1 year]. Revue de Chirurgie Orthopédique et Traumatologique.

2017;103(7):S61. Article in French. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcot.2017.09.092

72

Remy

S

,

Detrembleur

C

,

Libouton

X

,

Bonnelance

M

,

Barbier

O

. Trapeziometacarpal prosthesis: an updated systematic review. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2020;39(6):492–501. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hansur.2020.08.005

73

Russo

S

,

Bernasconi

A

,

Busco

G

,

Sadile

F

. Treatment of the trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis by arthroplasty with a pyrocarbon implant. Int Orthop. 2016;40(7):1465–71. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-015-3016-z

74

Barrera-Ochoa

S

,

Vidal-Tarrason

N

,

Correa-Vázquez

E

,

Reverte-Vinaixa

MM

,

Font-Segura

J

,

Mir-Bullo

X

. Pyrocarbon interposition (PyroDisk) implant for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: minimum 5-year follow-up. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2150–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2014.07.011

75

Erne

HC

,

Schmauß

D

,

Cerny

M

,

Schmauss

V

,

Ehrl

D

,

Löw

S

, et al.

Resektionsarthroplastik nach Lundborg vs. Pyrocarbon-Spacer (Pyrocardan®) bei fortgeschrittener Rhizarthrose – Eine Zwei-Center-Studie [Lundborg’s resection arthroplasty vs. Pyrocarbon spacer (Pyrocardan®) for the treatment of trapeziometacarpal joint osteoarthritis: a two-centre study]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2017;49(3):175–80. Article in German. dio:.https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-115220

76

Oh

WT

,

Chun

YM

,

Koh

IH

,

Shin

JK

,

Choi

YR

,

Kang

HJ

. Tendon versus Pyrocarbon Interpositional Arthroplasty in the Treatment of Trapeziometacarpal Osteoarthritis. BioMed Res Int. 2019;2019:7961507. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/7961507

77

Gerace

E

,

Royaux

D

,

Gaisne

E

,

Ardouin

L

,

Bellemère

P

. Pyrocardan® implant arthroplasty for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2020;39(6):528–38. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hansur.2020.09.003

78

Odella

S

,

Querenghi

AM

,

Sartore

R

,

DE Felice

A

,

Dacatra

U

. Trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis: pyrocarbon interposition implants. Joints. 2015;2(4):154–8.

79

Lauwers

TM

,

Brouwers

K

,

Staal

H

,

Hoekstra

LT

,

van der Hulst

RR

. Early outcomes of Pyrocardan® implants for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2016;35(6):407–12. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hansur.2016.09.004

80

Gauthier

E

,

Truffandier

MV

,

Gaisne

E

,

Bellemère

P

. Treatment of scaphotrapeziotrapezoid osteoarthritis with the Pyrocardan® implant: Results with a minimum follow-up of 2 years. Hand Surg Rehabil. 2017;36(2):113–21. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hansur.2017.01.003

81

De Smet

L

,

Van Meir

N

,

Verhoeven

N

,

Degreef

I

. Is there still a place for arthrodesis in the surgical treatment of basal joint osteoarthritis of the thumb?

Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76(6):719–24.

82

Rizzo

M

,

Moran

SL

,

Shin

AY

. Long-term outcomes of trapeziometacarpal arthrodesis in the management of trapeziometacarpal arthritis. J Hand Surg Am. 2009;34(1):20–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2008.09.022

83

Hartigan

BJ

,

Stern

PJ

,

Kiefhaber

TR

. Thumb carpometacarpal osteoarthritis: arthrodesis compared with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83(10):1470–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2106/00004623-200110000-00002

84

Taylor

EJ

,

Desari

K

,

D’Arcy

JC

,

Bonnici

AV

. A comparison of fusion, trapeziectomy and silastic replacement for the treatment of osteoarthritis of the trapeziometacarpal joint. J Hand Surg [Br]. 2005;30(1):45–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JHSB.2004.08.006