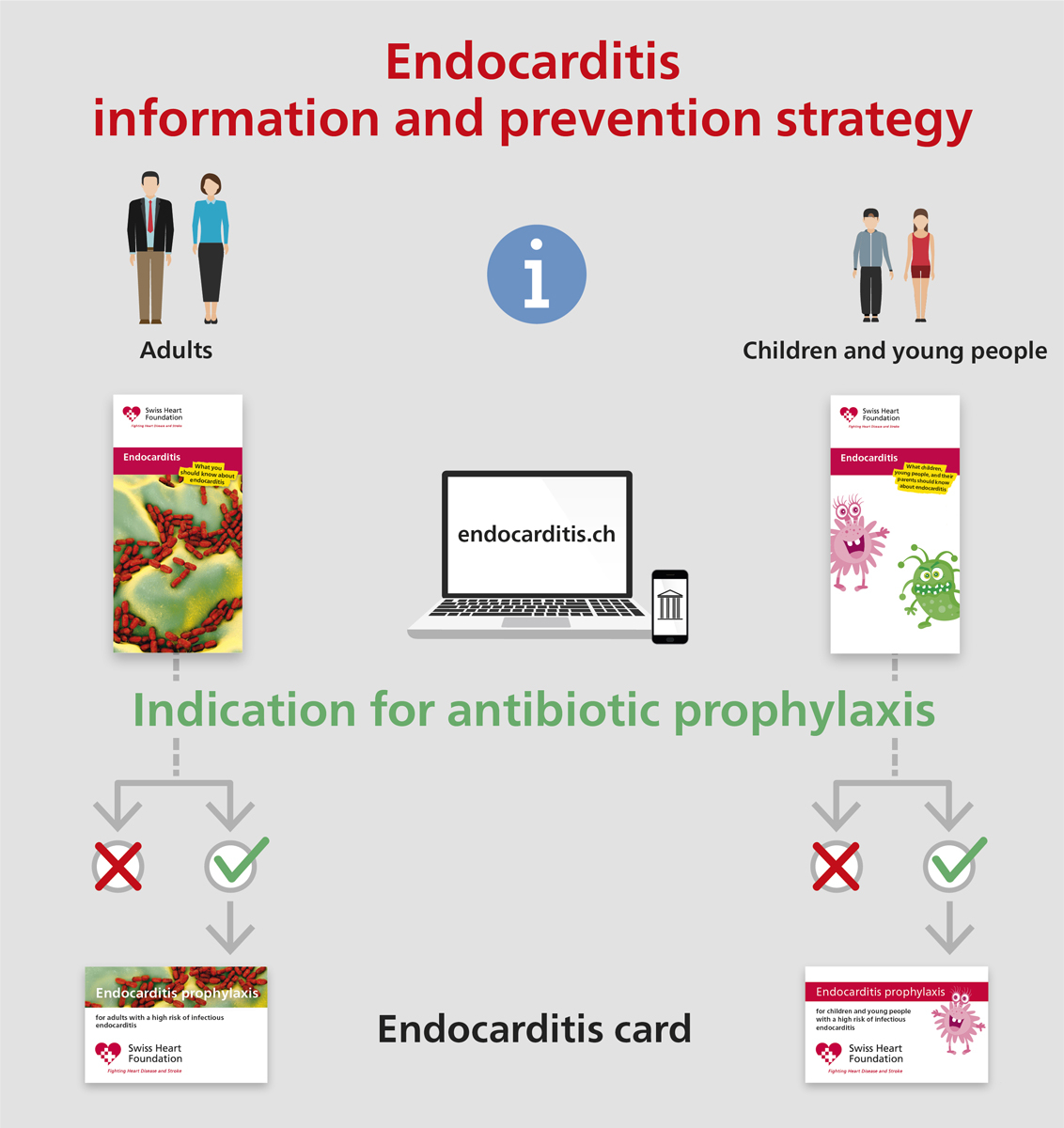

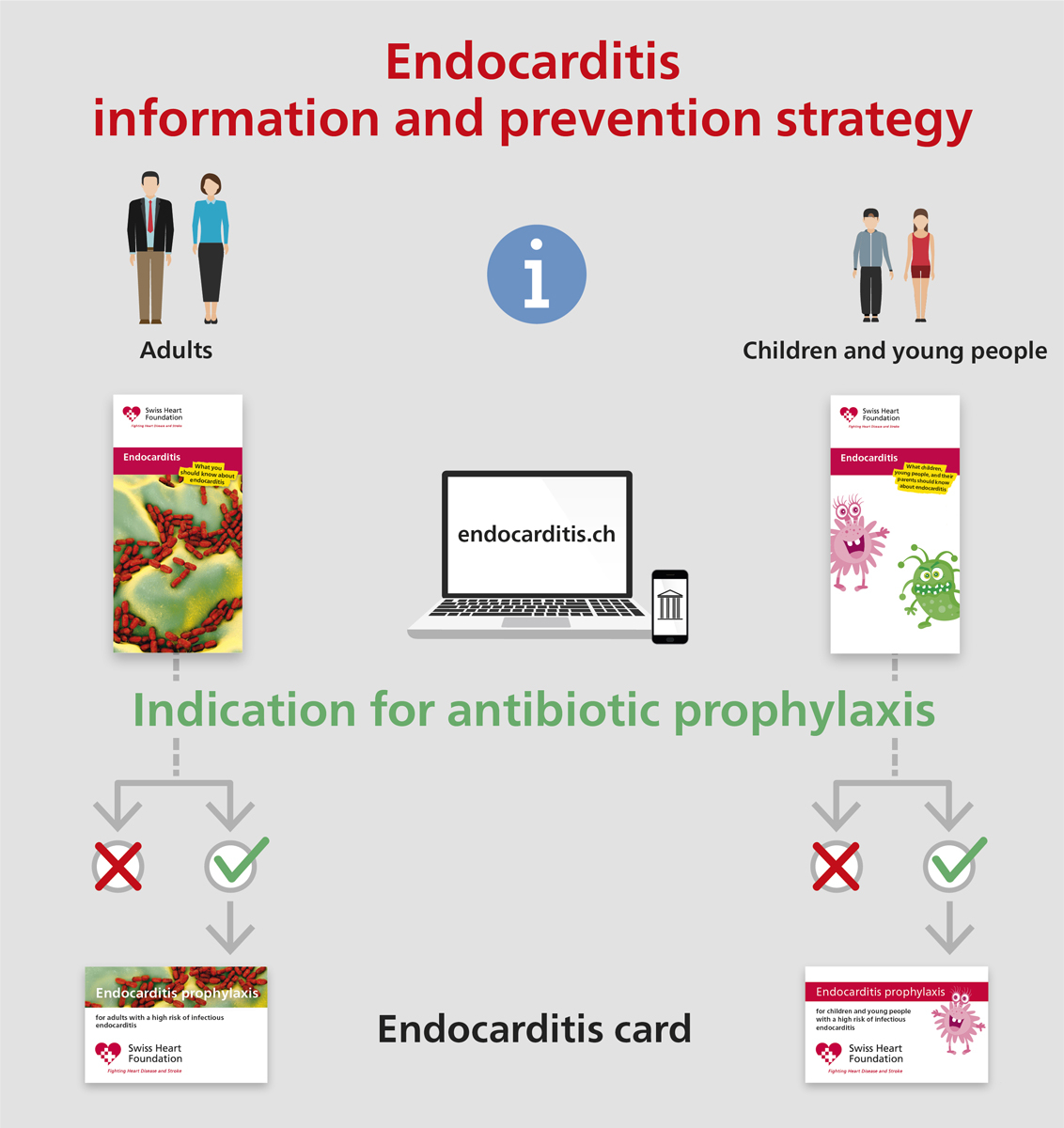

Figure 1 Information and prevention strategy: prevention campaign for all patients at risk for infective endocarditis.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20473

The Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases (SSI), with the support of the Federal Office of Public Health, initiated a platform for clinical practice guidelines in 2017. The goal of these guidelines is to optimise and possibly reduce antibiotic use in Switzerland [1]. After considerable revision of the previous guidelines on infective endocarditis prophylaxis by the American Heart Association in 2007, the Swiss recommendations were revised and published in 2008 [2]. The SSI and the Swiss Society of Cardiology together with the Swiss Society for Paediatric Cardiology and the Paediatric Infectious Disease Group of Switzerland are presenting the current update as a joint initiative. Following the standard procedure of establishing SSI guidelines, the expert group reviewed existing and published international guidelines and selected one of them as the designated reference guidelines. For the subject “Prevention of Infective Endocarditis”, the recommendations of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) 2015 were selected [3]. Deviations in the wording of the text and adaptation of the recommendations in accordance with the Swiss health care system were formulated by the expert group and concisely presented as the “Swiss Guideline Digest”. This summary is freely available on the web (https://ssi.guidelines.ch/ → Infective Endocarditis/Prevention).

Traditionally, either the term “antibiotic prophylaxis” or “endocarditis prophylaxis” is used to mean the administration of an antimicrobial agent prior to an intervention (e.g., in dental medicine). The goal of antibiotic prophylaxis is the rapid elimination of a transitory bacteraemia that can occur during an intervention. Hence, the aim is to reduce the risk of developing infective endocarditis. Several studies have indicated, however, that only a small proportion of cases of infective endocarditis are associated with a previous dental intervention and that the association of infective endocarditis with skin or mucosal injuries through daily activities appears to have a much higher impact on the total number of infective endocarditis cases. This observation prompted the providers of national and international guidelines to focus on general prevention strategies, including comprehensive patient education about the potential risks of developing an infective endocarditis and recommendations for skin and dental hygiene precautions. Thus, the terminology “prevention and prophylaxis” is important and should be used in future.

Depending on the severity of the heart disease and valvulopathy, the risk for infective endocarditis is categorised as moderate (or intermediate) or high [4]. After the indication for antibiotic prophylaxis was restricted to only one risk group (i.e., those at high risk for infective endocarditis), studies from England reported a reduction in antibiotic prescriptions and an increase in the incidence of infective endocarditis [5, 6]. Consequently, the results of these studies were discussed again, and broadening the indication for antibiotic prophylaxis was also considered [7, 8]. Conversely, other studies during the same period did not observe an increase in the incidence of infective endocarditis [9, 10]. Moreover, recent large epidemiological studies in the United States [11] and Europe [12] demonstrated that – despite changes in antibiotic prophylaxis guidelines – the incidence of infective endocarditis remained stable from 1998 to 2013 and 1990 to 2014, respectively. In agreement with the ESC 2015 guidelines, the Swiss expert group recommends antibiotic prophylaxis only for individuals at high risk and hence, for only one risk group. This recommendation has been valid in Switzerland since 2008 and continues to be so.

Among those in the high-risk group, patients with a history of infective endocarditis and with a prosthetic heart valve, or with a history of heart valve reconstruction and use of foreign body material, have the highest risk of infection [4]. Therefore, the indications for antibiotic prophylaxis in the high-risk group are presented in a specific ranked order. A few indications for antibiotic prophylaxis, previously listed in the 2008 recommendations, were removed because of lack of evidence. These indications include ventricle septum defect or open ductus arteriosus without surgery.

Antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for interventions related to ear-nose-throat surgery, the skin, the respiratory tract, the gastrointestinal tract and the urogenital tract are not part of the specific antibiotic endocarditis prophylaxis recommendations for two reasons. First, most abdominal and gynaecological surgical interventions are performed in a hospital setting, and Swissnoso has published recommendations for perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis [13] that apply to all patients, including those with an elevated risk for infective endocarditis. A few exceptions for high-risk patients are published on the SSI website (https://ssi.guidelines.ch/ → Infective Endocarditis/Prevention, Box 3), such as antibiotic treatment for incision of a skin abscess, or antimicrobial agent options for abdominal surgery (i.e., amoxicillin/clavulanic acid instead of cefuroxime or cefazolin to cover activity against Enterococcus spp.). Second, the Swiss Society for Gastroenterology published specific antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for endoscopic interventions [14]. For these reasons, recommendations for an endocarditis card (similar to an allergy passport carried by patients) is limited to dental interventions. For non-dental interventions, we refer to published recommendations of various societies [13, 14] and those of the SSI (list below and https://ssi.guidelines.ch/ → Infective Endocarditis/Prevention).

Antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for local anaesthetic injections in non-infected tissues, treatment of superficial caries, removal of sutures, dental X-rays, placement or adjustment of removable prosthodontic or orthodontic appliances or braces, the period following the shedding of deciduous teeth, or superficial trauma to the lips and oral mucosa.

Antibiotic prophylaxis should only be administered for dental procedures with a tendency to bleed:

The antibiotic prophylaxis should be taken 1 hour prior to the intervention.

Amoxicillin

Alternatives in the case of penicillin allergy

In the case of inability to swallow the antibiotic pill

Alternatives in the case of penicillin allergy and inability to swallow the antibiotic pill

* There will be a separate antibiotic card for adults and children.

While developing the Swiss Digest recommendations, the members of the expert group discussed the following areas of uncertainty thoroughly.

Antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac transplant recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy is not supported by evidence and is not recommended by the ESC [3]. Conversely, the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT, 2010) recommends prophylaxis in cardiac transplant recipients who develop cardiac valvulopathy [15]. Transplant patients have a high risk of developing tricuspid regurgitation [16]; nonetheless, only a few (heterogeneous) publications are available on tricuspid regurgitation and the risk of developing infective endocarditis [17, 18]. The rationale for the ISHLT recommendations (expert opinions and consensus statement) relies on the observation of severe clinical courses with a high mortality rate in transplant patients with infective endocarditis [19]. The expert group confirms that there is no scientific evidence to support a recommendation for or against antibiotic prophylaxis in cardiac transplant patients who develop valvulopathy. The majority of the expert group members follow the recommendations of the ESC 2015 [3]. At the same time, the expert group states that it is not meaningful to express a generalisable recommendation in Switzerland for a relatively small patient population with (different) complex disease histories. Because all heart transplant patients are followed up in specialised institutions, it is the responsibility of the treating transplant physician to prescribe antibiotic prophylaxis prior to the intervention, as evaluated on a case-by-case basis.

Bacteraemia occurs frequently during tonsillectomy [20–23]. However, perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for tonsillectomy in patients without risk for developing infective endocarditis [13, 24]. Because of the lack of evidence, the ESC has not published any recommendations for patients with risk factors for developing infective endocarditis. The majority of the expert group favour the administration of antimicrobial prophylaxis in high-risk patients who are undergoing tonsillectomy [2, 23, 25]. The antimicrobial agent must have activity against organisms belonging to the oral microbiome (e.g., amoxicillin 2 g or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 2.2 g in adults, and 50 mg/kg [maximum dose 2.2 g] in children intravenously 30 minutes prior to incision). However, because of lack of evidence, the expert group clearly categorises this statement as expert opinion and not as guideline recommendations.

The endocarditis prophylaxis recommendations presented herein differ in only minor points in comparison to those published in 2008. The revised recommendations mainly relied on a comprehensive prevention campaign for all patients at risk for infective endocarditis (fig. 1).

Figure 1 Information and prevention strategy: prevention campaign for all patients at risk for infective endocarditis.

The information strategy includes the following key elements:

Considering that the rapid diagnosis and correct treatment of infective endocarditis can be life-saving, patient education is a central element in the prevention strategy. For this reason, the Swiss expert group is collaborating with the Swiss Heart Foundation. An information flyer that illustrates the most important issues about infective endocarditis has been generated and is being distributed to all patients at risk for infective endocarditis (fig. 1). The purpose of this flyer is patient education and as a supportive instrument for caregivers and providers in the field of heart disease. Patients at highest risk for infective endocarditis require antibiotic prophylaxis prior to certain dental interventions, and only these patients will receive an antibiotic card (fig. 1). Different versions of flyers and cards are available for adults and children. For non-dental interventions, specific recommendations can be found on the corresponding websites (fig. 2). Additional patient information can also be found on the following websites: https://www.endocarditis.ch [German] and https://www.endocardite.ch [French]. Development of an educational movie is in progress.

Figure 2 Patients with the highest risk for infective endocarditis require antibiotic prophylaxis prior to dental interventions. Only these patients will also receive a separate antibiotic card. For non-dental interventions, specific recommendations can be found on the corresponding websites.

We are indebted to the Swiss Heart Foundation for the excellent collaboration and generous support regarding public information. We thank Prof. Dr. med. dent. Michael Bornstein, Department of Oral Health and Medicine, University Centre for Dental Medicine Basel UZB, University of Basel, Basel, Switzerland, for his support on aspects of dental medicine.

A German and French version of this article has been published in the journal Swiss Medical Forum (https://doi.org/10.4414/smf.2021.08717 and https://doi.org/10.4414/fms.2021.08717).

No financial support and no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

1 Vernazza P , Tschudin Sutter S , Kronenberg A , Hauser C, Huttner B, Manuel O, et al. Entwicklung infektiologischer Guidelines – ein kontinuierlicher Prozess. Swiss Med Forum. 2018;18(46):963–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smf.2018.03382

2 Jaussi A , Flückiger U . Revidierte schweizerische Richtlinien für die Endokarditis-Prophylaxe. Kardiovaskuläre Medizin. 2008;11(12):392–400. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/cvm.2008.01375

3 Habib G , Lancellotti P , Antunes MJ , Bongiorni MG , Casalta JP , Del Zotti F , et al.; ESC Scientific Document Group. 2015 ESC Guidelines for the management of infective endocarditis: The Task Force for the Management of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by: European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS), the European Association of Nuclear Medicine (EANM). Eur Heart J. 2015;36(44):3075–128. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehv319

4 Thornhill MH , Jones S , Prendergast B , Baddour LM , Chambers JB , Lockhart PB , et al. Quantifying infective endocarditis risk in patients with predisposing cardiac conditions. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(7):586–95. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehx655

5 Dayer MJ , Jones S , Prendergast B , Baddour LM , Lockhart PB , Thornhill MH . Incidence of infective endocarditis in England, 2000-13: a secular trend, interrupted time-series analysis. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1219–28. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62007-9

6 Thornhill MH , Gibson TB , Cutler E , Dayer MJ , Chu VH , Lockhart PB , et al. Antibiotic Prophylaxis and Incidence of Endocarditis Before and After the 2007 AHA Recommendations. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(20):2443–54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.08.2178

7 Geach T . Infective endocarditis rises as prophylactic antibiotic use falls. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12(1):5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2014.200

8 Duval X , Hoen B . Prophylaxis for infective endocarditis: let’s end the debate. Lancet. 2015;385(9974):1164–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62121-8

9 Bikdeli B , Wang Y , Krumholz HM . Infective endocarditis and antibiotic prophylaxis. Lancet. 2015;386(9993):528–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61467-2

10 Bikdeli B , Wang Y , Kim N , Desai MM , Quagliarello V , Krumholz HM . Trends in hospitalization rates and outcomes of endocarditis among Medicare beneficiaries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(23):2217–26. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.07.071

11 Toyoda N , Chikwe J , Itagaki S , Gelijns AC , Adams DH , Egorova NN . Trends in Infective Endocarditis in California and New York State, 1998-2013. JAMA. 2017;317(16):1652–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.4287

12 Shah ASV , McAllister DA , Gallacher P , Astengo F , Rodríguez Pérez JA , Hall J , et al. Incidence, Microbiology, and Outcomes in Patients Hospitalized With Infective Endocarditis. Circulation. 2020;141(25):2067–77. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.044913

13Swissnoso. Nationales Zentrum für Infektionsprävention. Sample-Guideline: perioperative Antibiotikaprophylaxe. Available at: https://www.swissnoso.ch/fileadmin/module/ssi_intervention/Dokumente_D/4_Sample_Guidelines/180816_Sample-Guideline_AMP_de.pdf.

14Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie; Société Suisse de Gastroentérologie; Societa Svizzera di Gastroenterologia. Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Available at: https://sggssg.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/Antibiotikaprophylaxe_in_der_Gastroenterologie_2018.pdf.

15 Costanzo MR , Dipchand A , Starling R , Anderson A , Chan M , Desai S , et al., International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines. The International Society of Heart and Lung Transplantation Guidelines for the care of heart transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2010;29(8):914–56. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2010.05.034

16 Wong RC , Abrahams Z , Hanna M , Pangrace J , Gonzalez-Stawinski G , Starling R , et al. Tricuspid regurgitation after cardiac transplantation: an old problem revisited. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2008;27(3):247–52. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2007.12.011

17 Büchi A , Hoffmann M , Zbinden S , Atkinson A , Sendi P . The Duke minor criterion “predisposing heart condition” in native valve infective endocarditis - a systematic review. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14675. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14675

18Buechi AE, Hoffmann M. Infective endocarditis [Dr. med.]. Bern: University of Bern, 2017.

19 Sherman-Weber S , Axelrod P , Suh B , Rubin S , Beltramo D , Manacchio J , et al. Infective endocarditis following orthotopic heart transplantation: 10 cases and a review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2004;6(4):165–70. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3062.2004.00074.x

20 François M , Bingen EH , Lambert-Zechovsky NY , Mariani-Kurkdjian P , Nottet JB , Narcy P . Bacteremia during tonsillectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118(11):1229–31. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.1992.01880110097017

21 Kaygusuz I , Gök U , Yalçin S , Keleş E , Kizirgil A , Demirbağ E . Bacteremia during tonsillectomy. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2001;58(1):69–73. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-5876(00)00471-7

22 Yildirim I , Okur E , Ciragil P , Aral M , Kilic MA , Gul M . Bacteraemia during tonsillectomy. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(8):619–23. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1258/002221503768199951

23 Klug TE , Henriksen JJ , Rusan M , Fuursted K , Ovesen T . Bacteremia during quinsy and elective tonsillectomy: an evaluation of antibiotic prophylaxis recommendations for patients undergoing tonsillectomy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17(3):298–302. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248411423023

24 Milder EA , Rizzi MD , Morales KH , Ross RK , Lautenbach E , Gerber JS . Impact of a new practice guideline on antibiotic use with pediatric tonsillectomy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(5):410–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2015.95

25 Wilson W , Taubert KA , Gewitz M , Lockhart PB , Baddour LM , Levison M , et al.; American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young; American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology; American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736–54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.183095

No financial support and no other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.