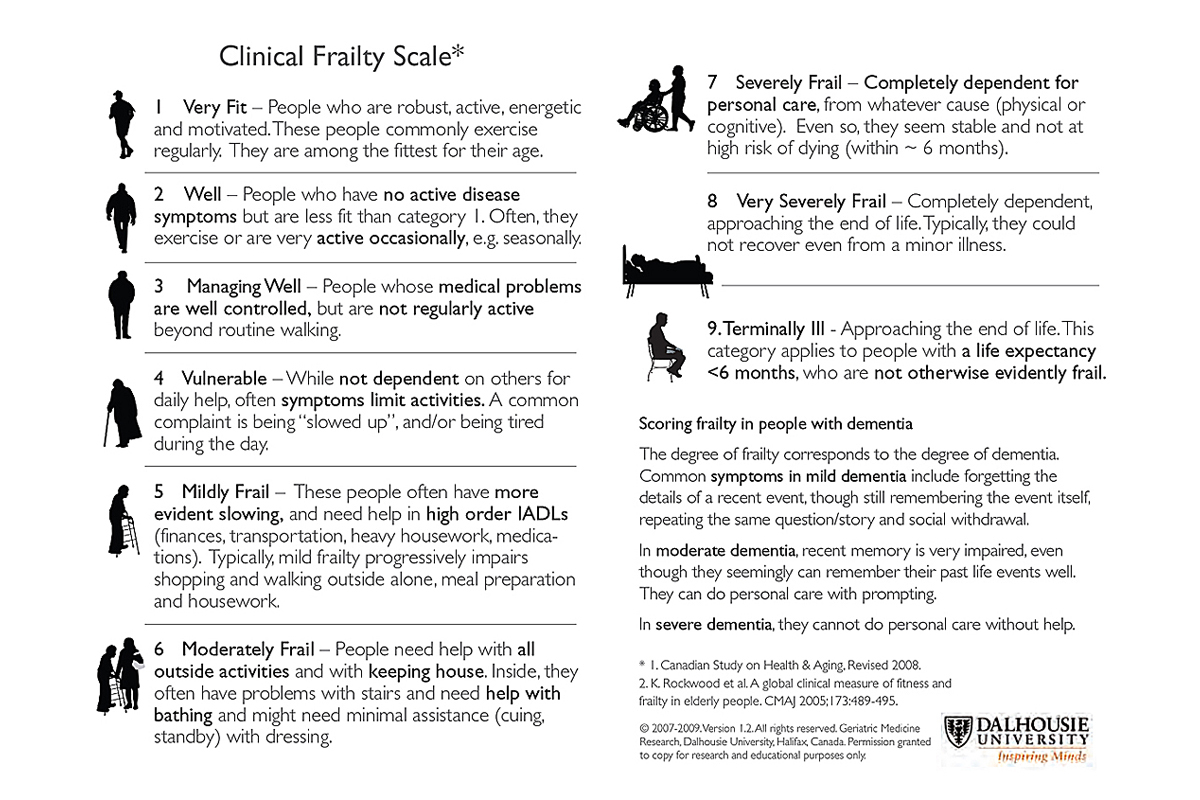

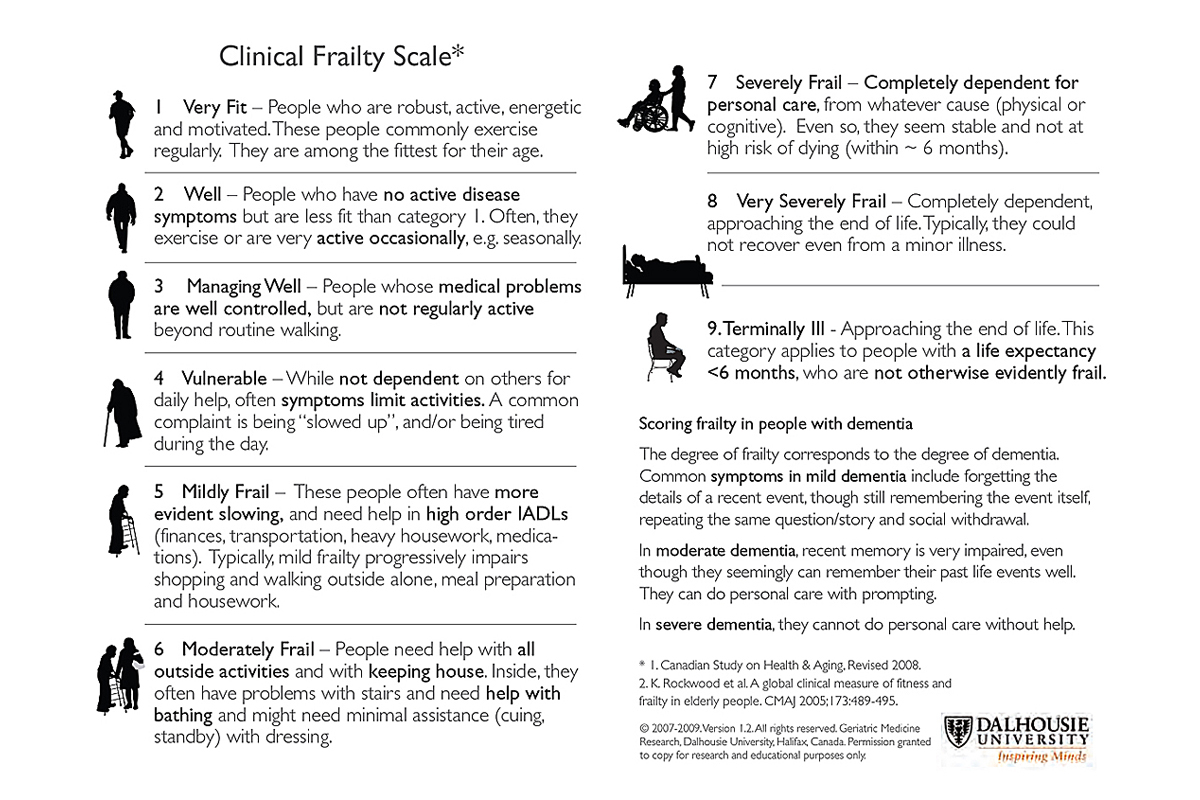

Figure S1 Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2021.20458

Guidance on the application of Section 9.3 of the SAMS Guidelines “ Intensive-care interventions ” (2013)

This document is available in English, French, German and Italian, cf. sams.ch/en/coronavirus. The German text is the authentic version.

Updated version of 17 December 2020. Former versions were published in the Swiss Medical Weekly in March 2020 (Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20229, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20229 ) and November 2020 (Swiss Med Wkly. 2020;150:w20401, DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20401 )

In March 2020, owing to the rapid spread of the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2), an extraordinary situation1 was declared, and, as a result of high case numbers, acute hospitals experienced a massive influx of patients over a period of several weeks. In view of this situation, the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) and the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SSICM) issued guidelines on triage for intensive-care treatment under resource scarcity. In this first wave of COVID-19, the restriction of elective procedures2 and an increase in intensive care unit (ICU) capacity (particularly ventilator-equipped beds), together with public health (behavioural) measures ordered by the federal government, were enough to prevent a situation of resource scarcity from arising at the national level. It was therefore not necessary for the SAMS guidelines to be applied.

Given the development of the pandemic in October, it was necessary for the guidelines to be revised in the light of the experience accumulated since March, and an updated version was issued (version 3). There has been no change in the guiding principle that uniform criteria for ICU admission and continued occupancy should be applied throughout Switzerland. The present version (3.1) differs from the preceding versions in that it clarifies and explains the ethical principles which have been applied since March. In addition, it includes an assessment and further consideration of legal aspects. The recommendations for the work and decision-making of ICU professionals are essentially unchanged.

In accordance with the statement issued by the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SSICM) on 17 November 20203, it is to be noted from an ethical perspective that responsibility for ensuring the availability of ICU capacity does not lie solely with the hospitals that offer such facilities; these efforts rely on the participation and shared responsibility of society and policymakers. This means it is essential for control measures to be ordered, implemented and complied with, that support the health system as effectively as possible and relieve pressure on capacity.

In collaboration with various health system actors, the Coordinated Medical Services of the Swiss Armed Forces has established a system for national coordination of ICUs. A central coordination body is to ensure that optimum use is made of all ICU treatment capacity available across Switzerland.4

As specified in the document “National coordination in the event of a massive influx of patients to ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic”5, responsibility for patient triage lies with the individual hospital/ICU. At the same time, the obligation of hospitals and ICUs to admit patients is limited by the capacity available. The SAMS and the SSICM hereby propose that the national coordination body should be responsible for determining at what point the situation in Switzerland is such that triage decisions – in accordance with the criteria set out here – are unavoidable. This would ensure that the best possible use is made of resources across Switzerland before triage decisions are required at individual hospitals.

The coordination body should also be responsible for deciding on the threshold at which the application of these guidelines is to be triggered at the national level. If this threshold has not been reached nationally, but an acute scarcity of ICU capacity exists at the local or regional level and neither transport nor admission to another ICU is possible – despite an increase in ICU beds, the suspension of elective procedures and the involvement of the national coordination body for patient transfers – then these guidelines are to be applied mutatis mutandis at the local or regional level. The SAMS and the SSICM recommend that hospitals should inform the national coordination body about the application of the guidelines.

The guidelines will be adapted by the SAMS and the SSICM if experience in practice and new scientific findings so require. The latest version is available at: sams.ch/en/coronavirus

These guidelines concerning the criteria for ICU triage are applicable for the point in time at which resource scarcity arises and rationing decisions have to be made. They are applicable to all patient categories. Patients with COVID-19 and other patients requiring intensive care are treated according to the same criteria.

The guidelines supplement the SAMS Guidelines “Intensive-care interventions” (2013). Accordingly, in the event of resource scarcity, they will apply only to a small proportion of patients, namely the group of severely ill patients requiring intensive care. The guidelines are to be applied by intensive care professionals, in consultation – depending on the context – with specialists in other disciplines such as emergency medicine, internal medicine or palliative care.

The four widely recognised principles of medical ethics (beneficence, non-maleficence, respect for autonomy and equity) are also crucial under conditions of resource scarcity. It is important that the patient’s wishes with regard to emergency treatment and intensive care are ascertained at an early stage, especially for individuals belonging to a risk group. Scarce resources must never be employed for treatments that a patient does not wish to receive.

If the resources available are insufficient to enable all patients to receive the ideally required treatment, then these fundamental principles are to be applied in accordance with the following rules of precedence:7

Equity: Available resources are to be allocated without discrimination – that is, without unjustified unequal treatment on grounds of age, sex, residence8, nationality, religious affiliation, social or insurance status, or disability. The allocation procedure must be fair, objectively justified and transparent. In a situation of acute scarcity of ICU beds, equal dignity is still to be accorded to each individual. If intensive care cannot be provided, alternative treatment and care options – in particular, palliative care – are to be made available.

Preserving as many lives as possible: In the event of acute scarcity of ICU beds, all measures are guided by the aim of minimising the number of deaths. Decisions should be made in such a way as to ensure that as few people die as possible.

Protection of the professionals involved: These individuals9 are at particular risk of infection with the coronavirus. If they are unable to work owing to infection, more deaths will occur under conditions of acute resource scarcity. They are therefore to be protected as far as possible against infection, but also against excessive physical and psychological stress. Professionals whose health is at greater risk in the event of infection with the coronavirus are to be especially protected and should not be deployed in the care of patients with COVID-19.

These guidelines are intended to support decision-making by professional treatment teams. Triage ultimately involves case-by-case decisions, in which the experience of the team plays a crucial role. In individual cases, in order to elaborate the primary criterion of short-term prognosis, additional medical prognostic criteria may need to be taken into account.

As long as sufficient resources are available, patients requiring intensive care are to be admitted and treated in accordance with established criteria. Particularly resource-intensive interventions should be undertaken only in cases in which the benefits thereof have been unequivocally demonstrated. In a situation of acute resource scarcity, they run counter to the goal of saving the maximum possible number of lives. In such a context, therefore, ECMO10, for example, should only be used in particular situations, as specified in the SSICM guidelines11, after careful assessment of the resources required.12

It is necessary to discuss in advance – with all patients capable of doing so – the patient’s wishes in the event of possible complications (resuscitation status and extent of intensive care). In the case of patients who lack capacity, this involves consideration of their presumed wishes in consultation with their authorised representatives. If intensive-care interventions are withheld, comprehensive palliative care must be provided.13 To avoid ICU resource scarcity, it is also crucial that departments and institutions providing care for patients discharged from an ICU (or instead of intensive-care treatment) fulfil their obligations in a spirit of solidarity.

If ICU capacity is exhausted and not all patients who require intensive care can be admitted, the short-term survival prognosis is decisive for purposes of triage. For ICU admission, highest priority is to be accorded to those patients whose prognosis14 with regard to hospital discharge is good with intensive care, but poor without it – that is, the patients who will benefit most from intensive care. The aim is to make decisions in such a way as to save the largest possible number of lives.

Age, disability or dementia in themselves are not to be applied as criteria. This would infringe the constitutional prohibition on discrimination, since people who are older, disabled or suffer from dementia would thereby be accorded less value than others. In general, for patients requiring intensive care, a poor short-term prognosis is not be automatically inferred from age, disability or dementia alone. If a patient is to be accorded lower priority for intensive care, there must always be specific risk factors for increased mortality and hence a poor short-term prognosis.

A specific risk factor for increased mortality is, for example, age-related frailty. In older people, this is correlated with a poor short-term prognosis, and it is therefore a relevant criterion to be taken into account in a situation of resource scarcity. Of the various tools proposed for the evaluation of frailty, the best validated15 is the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS, cf. fig. S1 in appendix 1).

A disability is not in itself a factor of prognostic relevance; in persons with disabilities, there may, however, be comorbidities that are directly associated with the disability (e.g., respiratory insufficiency in a person with multiple disabilities) or not directly associated (e.g., cancer in a person with quadriplegia). However, in persons with disabilities, dependence on assistance for activities of daily living is not correlated with the short-term prognosis. The CFS is not validated for the assessment of frailty in persons with disabilities and is thus not relevant here. Health status is to be determined in the same way for all persons, irrespective of any disabilities. Any other approach would be discriminatory and is thus to be rejected.

Consideration of additional criteria. In the literature,16 additional criteria are discussed, such as allocation by lottery, the “first come, first served” principle, and prioritisation of persons expected to have more quality-adjusted life years or deemed socially useful. These criteria are not to be applied.

The competent federal and cantonal authorities, as well as hospitals with ICUs, are essentially obliged to take all reasonable measures to prevent an acute shortage of ICU capacity. Apart from an increase in the number of ICU beds across Switzerland, the coordination of ICUs (cf. “Background” section I above) and the suspension of elective procedures, this also involves efforts to assess the availability of ICU capacity in collaboration with authorities and hospitals abroad. Conversely, if sufficient resources are available, Swiss ICUs should admit patients from neighbouring countries facing triage situations.

If, in spite of such measures, ICU capacity – including additional external beds – is no longer sufficient, only patients who require mechanical ventilation (or another specific intensive-care intervention, such as haemodynamic support with vasoactive agents or continuous renal replacement therapy) are to be admitted. In such situations, the utmost restraint is to be exercised in the application of cardiopulmonary resuscitation following cardiac arrest – with the exception of situations where an excellent outcome is to be expected.17

If not all patients requiring intensive care according to the above-mentioned criteria can be admitted to an ICU, decisions need to be made concerning patient admission to, or transfer from, the ICU. These are to be made according to the criteria of short-term survival prognosis, as explained in detail below. The criteria are linked to two stages (A and B), becoming more stringent as capacity pressures increase. All less intensive treatments should be carried out in intermediate (IMCUs) or standard care units.

Stage A: ICU beds available, but national capacity is limited, and there is reason to believe that, within a few days, ICU beds may become unavailable in Switzerland and transfers to ICUs abroad may not be possible to a sufficient extent.

Stage B: No ICU beds available.

Step 1:

Does the patient have any of the following inclusion criteria?

If one of these inclusion criteria is fulfilled → Step 2

Step 2:

Does the patient have any of the following exclusion criteria?

Stage A (cf. 4.2.)

In patients with COVID-19, the 4C Mortality Score may additionally be employed. A score of >15 indicates high mortality.19

Stage B (cf. 4.2)

Here, the following additional exclusion criteria are applied:

In Stage B, no cardiopulmonary resuscitation is to be performed in the ICU.

The following criteria are relevant for the continuation of ICU treatment:

The health status of patients in the ICU is to be assessed daily and interprofessionally.

Here, the medical utility of intensive care is be evaluated on the basis of the clinical course – partly to allow decisions to be taken regarding a possible transition from curative treatment to palliative care. This applies to all (i.e. both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19) patients receiving ICU treatment when resources are exhausted. The more acute resource scarcity becomes, the more stringently the following criteria are to be applied.

Step 1:

Presence of a criterion for transfer from the ICU:

Step 2:

Following a period of stabilisation in accordance with the particular condition:

Presence of the following three criteria:

All three criteria must be met for ICU treatment to be continued.

Step 3:

Applicable in Stages A and B:

In Stage A (cf. 4.2), ICU treatment should be discontinued if one of the following criteria applies, even if all three criteria specified in Step 2 were met.

In Stage B (cf. 4.2), ICU treatment should be discontinued if one of the following criteria applies, even if all three criteria specified in Step 2 were initially met:

The presence of one these criteria and the discontinuation of ICU treatment leads to the initiation of palliative care for the patient.

NB: From a legal perspective, there is some uncertainty as to whether deaths occurring as a result of non-admission to, or transfer from, an ICU, in accordance with the criteria specified in these guidelines, are to be recorded as an “unnatural death” (i.e., an unusual death) on the medical death certificate. This uncertainty relates in particular to cases where individuals have to be transferred from an ICU as a result of resource scarcity. In a situation of resource scarcity, in order to achieve the goal of saving as many lives as possible and applying the criterion of short-term survival prognosis, triage decisions have to be taken both for ICU admission and during the ICU stay.

In this regard, the SAMS and the SSICM would welcome legal clarification in the interests of legal certainty for the medical profession. The SAMS and the SSICM currently recommend that the specific circumstances of these deaths should be documented, but that they should not be classified as unusual deaths. This remains subject to orders or decisions made by competent authorities or courts, requiring such cases to be reported as unusual deaths.

In triage decisions, confidence must be maintained under the most difficult conditions. For this reason, fair prioritisation criteria and fair processes must be transparently applied at all times. Clear reasons for according (or failing to accord) priority must be documented and updated as the situation develops. The same applies to the processes whereby such decisions are made. Individual decisions must be amenable to examination: they must be documented in writing and include a statement of reasons and the name of the person responsible. Any deviation from the specified criteria must be similarly documented. In addition, mechanisms should be in place for subsequent review of conflicts.

The decision-making process must be managed by experienced professionals. Whenever possible, decisions must be made within an interprofessional team, rather than by individuals. Ultimately, however, responsibility is borne by the most senior intensive care specialist present. Bodies providing support for treatment teams (e.g., ethics support, multiprofessional team) may be helpful. However, the ICU must be able to make rapid, independent decisions at any time on patient admissions and transfers. The legal requirements22 concerning the duty to provide regular reports on the total number and occupancy of ICU beds are to be complied with.

If, owing to a triage situation, ICU treatment is not offered or is discontinued, this must be communicated in a transparent manner. It is not permissible to justify the treatment decision to the patient on the grounds that such treatment is not indicated, if a different decision would have been taken had sufficient resources been available. The patient with capacity, or the relatives authorised to represent a patient lacking capacity, are to be openly informed about the decision-making process and, if possible, opportunities for further discussion should be offered, possibly supplemented by, for example, hospital pastoral care or psychological support.

1 The Ordinance 2 of 13 March 2020 on Measures to Combat the Coronavirus (COVID-19) (COVID-19 Ordinance 2) (status as of 17 March 2020; since revoked) was based on Article 7 of the Epidemics Act (SR 818.101), which regulates the “extraordinary situation”.

2 “Healthcare facilities such as hospitals and clinics, medical practices and dental practices must discontinue all non-urgent medical procedures and therapies” (Art. 10a para. 2 of the Ordinance cited in Footnote 1).

3 COVID-19: Vollständige Auslastung zertifizierter und anerkannter Intensivbettenkapazitäten (COVID-19: Certified and recognised ICU capacity fully utilised), dated 17 November 2020.

4 Further information and contact details can be found at: https://www.vtg.admin.ch/de/organisation/astab/san/ksd/nki.html (accessed on 14 December 2020).

5 Only available in German; accessed on 14 December 2020.

6 For a more detailed discussion of the ethical principles, see Section 2 of the SAMS Guidelines “Intensive-care interventions” (2013).

7 Cf. also Swiss Influenza Pandemic Plan, 2018, Part II, Section 6.1, and especially Part III, Section 6 “Ethical issues”.

8 Available hospital beds in intensive care must be reported; cf. Art. 12 of the Ordinance of 19 June 2020 on Measures during the Special Situation to Combat the COVID-19 Epidemic (status as of 12 December 2020).

9 Naturally, the same applies for all persons exposed to a higher risk of infection as a result of their work (e.g., retail and pharmacy staff, as well as relatives caring for patients).

10 Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.

11 Cf. SSICM, ECMO in COVID-19 related severe ARDS. ECMO Guidelines for non-ECMO Centers, 2020.

12 Cf. Bartlett et al. 2020.

13 Cf. the palliative.ch guidelines: Therapeutische Massnahmen bei Patienten mit Covid-19 mit zu erwartender ungünstiger Prognose (www.palliative.ch).

14 For a more detailed discussion of prognosis, see Section 5.1 of the SAMS Guidelines “Intensive-care interventions” (2013).

15 Cf. Hewitt et al. 2020.

16 Cf., for example, Persad et al. 2009.

17 Cf. the recommendations of the Swiss Society of Emergency and Rescue Medicine (SSERM): Prehospital triage and care under resource scarcity in the hospital sector (particularly in intensive care) during the COVID-19 pandemic, see www.sgnor.ch/home/covid-19

18 Cf. Christian et al. 2006.

19 Knight et al. 2020.

20 The justification for this criterion is the highly resource-intensive treatment required by patients with severe burns. In decision-making, the individual patient’s short-term survival prognosis is to be carefully considered and an assessment is to be made in accordance with capacity at the two Burn Units (USZ and CHUV).

21 Cf. Li et al. 2020.

22 Cf. the Ordinance of 19 June 2020 on Measures during the Special Situation to Combat the COVID-19 Epidemic (status as of 12 December 2020).

23 Cf. Flaatten et al. 2017; Muscedere et al. 2017; Rockwood et al. 2020; Surkan et al 2020.

Professor Samia Hurst, Université de Genève, Ethics (lead)

Professor Thierry Fumeaux, SSICM Past President, Nyon, Intensive Care Medicine

Dr Antje Heise, SSICM Medical President, Thun, Intensive Care Medicine

Bianca Schaffert, MSN, SAMS Central Ethics Committee Vice President, Schlieren, Nursing Sciences

Professor Arnaud Perrier, HUG Chief Medical Officer, Genève, General and Internal Medicine

Professor Bernhard Rütsche, Chair of Public Law and Philosophy of Law, Luzern, Law

Professor Tanja Krones, Head of Clinical Ethics USZ, Zürich, Ethics

Dr Thomas Gruberski, SAMS Ethics Department, Bern

lic. theol., Dipl. Biol. Sibylle Ackermann, SAMS Ethics Department, Bern

lic. iur. Michelle Salathé, SAMS Ethics Department, Bern (until September 2020)

Daniel Scheidegger, SAMS Vice President, Arlesheim (until November 2020)

Professor Eva Maria Belser, Fribourg

Professor Olivier Guillod, Neuchâtel

Professor Ralf Jox, Lausanne

Professor Brigitte Tag, Zürich

Professor Markus Zimmermann, Fribourg

Federal Bureau for the Equality of People with Disabilities

Inclusion Handicap – umbrella association of disability organisations in Switzerland

The SAMS and the SSICM thank the numerous other experts who commented on these guidelines and provided valuable input.

The guidelines – approved by the Central Ethics Committee (CEC), the Executive Board of the SAMS and the Board of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SSICM) – came into effect on 20 March 2020. The revised version 3.1 was approved by the CEC, the Executive Board of the SAMS and the Board of the SSICM on 11 December 2020.

Figure S1 Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS).

The Clinical Frailty Scale assists health professionals in assessing short-term survival prognosis in elderly patients. Its prognostic value is confirmed by numerous publications.23 At the same time, limited evidence is available concerning the most appropriate thresholds, which means that the scale needs to be used carefully, in combination with good clinical judgement on the part of the professionals concerned. The scale is to be employed by appropriately trained health professionals; training materials are available online at www.dal.ca/sites/gmr/our-tools/clinical-frailty-scale.html.

Please note: The latest literature on SARS-CoV-2 is made available on the website of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (SSICM) at https://www.sgi-ssmi.ch/de/.

Bartlett RH , Ogino MT , Brodie D , McMullan DM , Lorusso R , MacLaren G , et al. Initial ELSO Guidance Document: ECMO for COVID-19 Patients with Severe Cardiopulmonary Failure. ASAIO J. 2020;66(5):472–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/MAT.0000000000001173

Bouadma L , Lescure FX , Lucet JC , Yazdanpanah Y , Timsit JF . Severe SARS-CoV-2 infections: practical considerations and management strategy for intensivists. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(4):579–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05967-x

Bundesamt für Gesundheit (BAG). Influenza-Pandemieplan Schweiz. Strategien und Massnahmen zur Vorbereitung auf eine Influenza-Pandemie, 5. Auflage 2018, Kap. 6.1. sowie insb. Teil II.I «Ethische Fragen des Influenza-Pandemieplan Schweiz 2006», Stellungnahme der Nationalen Ethikkommission NEK-CNE Nr. 12/2006. www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/k-und-i/hygiene-pandemiefall/influenza-pandemieplan-ch.pdf.download.pdf/bag-pandemieplan-influenza-ch.pdf

Cheung WK , Myburgh J , Seppelt IM , Parr MJ , Blackwell N , Demonte S , et al.; Influenza Pandemic ICU Triage Study Investigators. A multicentre evaluation of two intensive care unit triage protocols for use in an influenza pandemic. Med J Aust. 2012;197(3):178–81. doi:.https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.10926

Christian MD , Hawryluck L , Wax RS , Cook T , Lazar NM , Herridge MS , et al. Development of a triage protocol for critical care during an influenza pandemic. CMAJ. 2006;175(11):1377–81. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060911

Flaatten H , De Lange DW , Morandi A , Andersen FH , Artigas A , Bertolini G , et al.; VIP1 study group. The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years). Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(12):1820–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4940-8

The Hastings Center. Ethical Framework for Health Care Institutions Responding to Novel Coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). Guidelines for Institutional Ethics Services Responding to COVID-19. Managing Uncertainty, Safeguarding Communities, Guiding Practice. 2020 March 16. www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/HastingsCenterCovidFramework2020.pdf

Hewitt J , Carter B , Vilches-Moraga A , Quinn TJ , Braude P , Verduri A , et al.; COPE Study Collaborators. The effect of frailty on survival in patients with COVID-19 (COPE): a multicentre, European, observational cohort study. Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(8):e444–51. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30146-8

Jöbges S , Vinay R , Luyckx VA , Biller-Andorno N . Recommendations on COVID-19 triage: international comparison and ethical analysis. Bioethics. 2020;34(9):948–59. Published online 2020 September 25. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12805

Knight SR , Ho A , Pius R , Buchan I , Carson G , Drake TM , et al.; ISARIC4C investigators. Risk stratification of patients admitted to hospital with covid-19 using the ISARIC WHO Clinical Characterisation Protocol: development and validation of the 4C Mortality Score. BMJ. 2020;370:m3339. Published online 2020 September 9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3339

Li QX , Zhao XJ , Fan HY , Li XN , Wang DL , Wang XJ , et al. Application Values of Six Scoring Systems in the Prognosis of Stroke Patients. Front Neurol. 2020;10:1416. Published online 2020 January 30. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.01416

Liao X , Wang B , Kang Y . Novel coronavirus infection during the 2019-2020 epidemic: preparing intensive care units-the experience in Sichuan Province, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(2):357–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-05954-2

MacLaren G , Fisher D , Brodie D . Preparing for the Most Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19: The Potential Role of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. JAMA. 2020;323(13):1245–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2342

Murthy S , Gomersall CD , Fowler RA . Care for Critically Ill Patients With COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(15):1499–500. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2762996. Published online 2020 March 11. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.3633

Muscedere J , Waters B , Varambally A , Bagshaw SM , Boyd JG , Maslove D , et al. The impact of frailty on intensive care unit outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2017;43(8):1105–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4867-0

Ñamendys-Silva SA . Respiratory support for patients with COVID-19 infection. Lancet. 2020;8(4):e18. Published online 2020 March 5. doi:. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30110-7

Österreichische Gesellschaft für Anaesthesiologie. Reanimation und Intensivmedizin (ÖGARI). Allokation intensivmedizinischer Ressourcen aus Anlass der Covid-19-Pandemie. Klinisch-ethische Empfehlungen für Beginn, Durchführung und Beendigung von Intensivtherapie bei Covid-19-PatientInnen. Statement der Arbeitsgruppe Ethik der ÖGARI vom 2020 March 17. www.oegari.at/web_files/cms_daten/covid-19_ressourcenallokation_gari-statement_v1.7_final_2020-03-17.pdf

Persad G , Wertheimer A , Emanuel EJ . Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet. 2009;373(9661):423–31. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60137-9

Rockwood K , Theou O . Using the Clinical Frailty Scale in Allocating Scarce Health Care Resources. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(3):254–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.23.463

Surkan M , Rajabali N , Bagshaw SM , Wang X , Rolfson D . Interrater Reliability of the Clinical Frailty Scale by Geriatrician and Intensivist in Patients Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit. Can Geriatr J. 2020;23(3):223–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.5770/cgj.23.398

Wu C , Chen X , Cai Y , Xia J , Zhou X , Xu S , et al. Risk Factors Associated With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and Death in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–43. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2763184. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994

Yang X , Yu Y , Xu J , Shu H , Xia J , Liu H , et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475–81. Published online 2020 February 24. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5

Zhou F , Yu T , Du R , Fan G , Liu Y , Liu Z , et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–62. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3