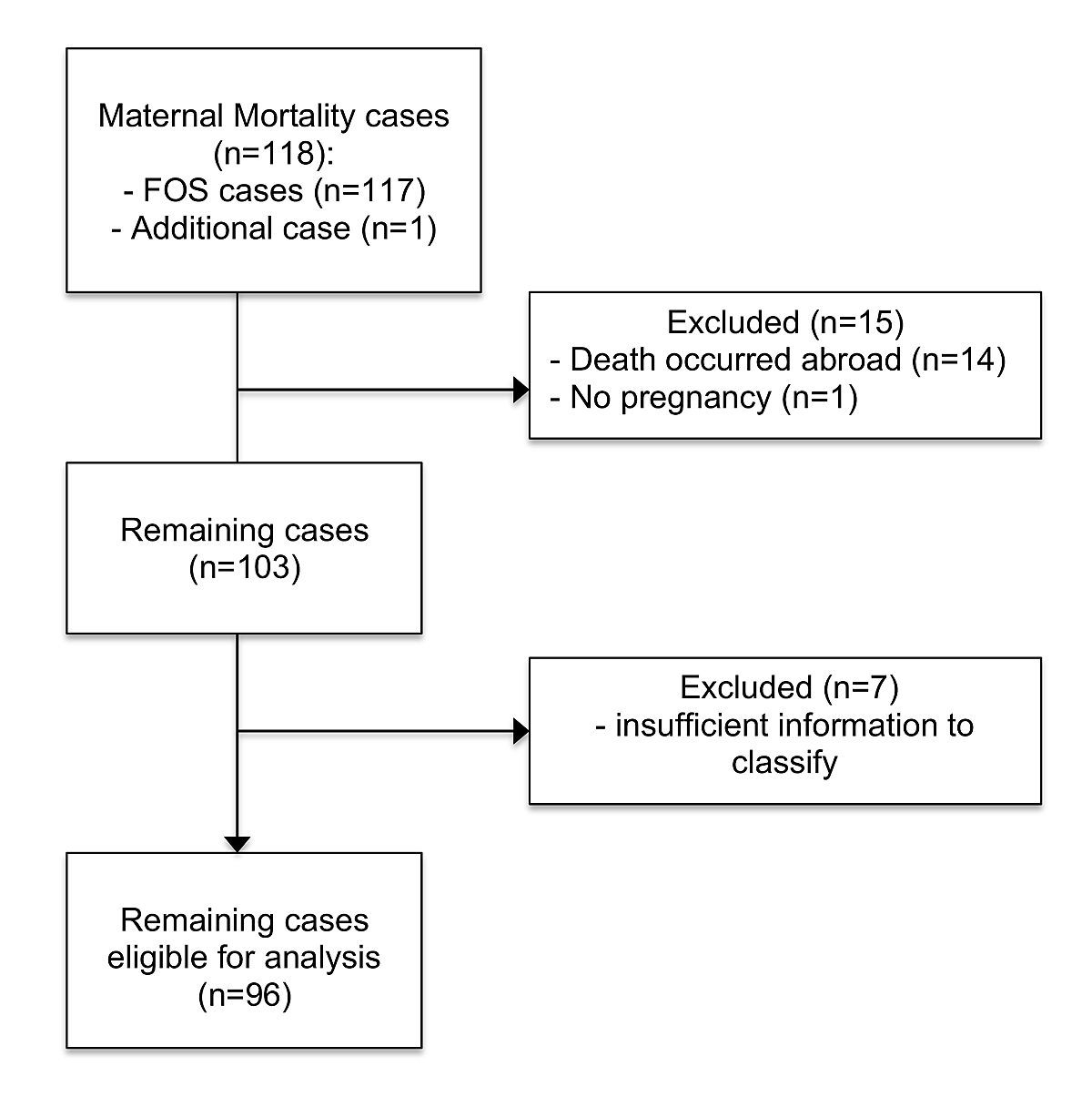

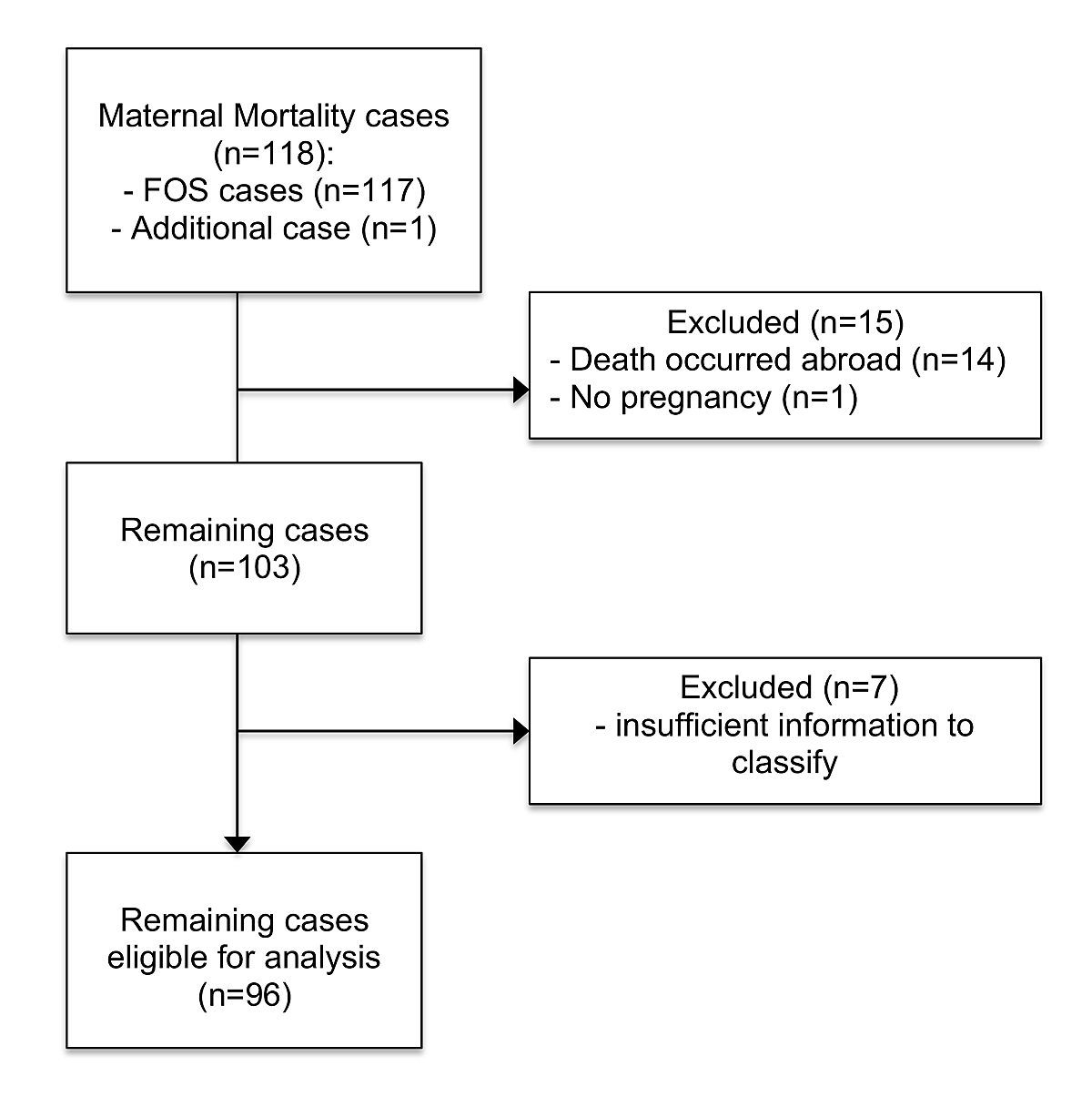

Figure 1 Flowchart: exclusion of cases.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20345

In 2015, roughly 303,000 women worldwide died during pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period [1]. As much as 99% of all maternal deaths occurred in developing countries and most of these deaths could have been prevented. From 1990 to 2015, global maternal mortality fell from 385/100,000 to 216/100,000 live births, a reduction of 43.9%. Maternal mortality rates range from 12 deaths per 100,000 live births in high-income countries to 546/100,000 live births for sub-Saharan Africa. Immediate action is needed in a bid to meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) target to reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70/100,000 live births by 2030 [2].

Pregnancy and childbirth have become continuously safer over the last 150 years in Switzerland. Nonetheless, maternal deaths still occur during this period and are tragic. Periodic analysis of maternal deaths is not only an important tool for quality assurance in obstetrics, but is also necessary to improve clinical care. As too little information is available in Switzerland for an annual analysis, a periodic analysis of maternal deaths has been carried out at 10-year intervals since 1985. In our study, we investigated the 10-year period between 2005 and 2014, having been preceded by two papers analysing the timespan from 1985 to 2004 [3, 4].

The main outcome of this study was to determine the ratios and causes of maternal mortality in Switzerland from 2004–2015 and to compare the results of this study period with the previously analysed study periods, including age and origin of the women. The secondary outcomes included estimation of underreporting based on a cohort in the canton of Zurich, as well as calculation of the lethality of caesarean section compared with vaginal delivery and making comparisons between the maternal mortality ratios in Switzerland and neighbouring countries in Europe.

The Federal Statistical Office (FSO) provided maternal death certificates for the years 2005 to 2014. All death certificates having an ICD-10 classification code in the obstetric field as well as all death certificates with the code “F53” (puerperal psychosis) were included. When reporting the death of a female aged 15–49 years, it is mandatory to mention in the death certificate whether the woman was pregnant at the time of her death or if she had given birth on any of the previous 42 days leading up to her death. Additionally, since 2007, birth data can be linked with the date of death of the mother, thus allowing identification of women who had given birth in the year before death. Therefore, cases where death occurred within 365 days after delivery were included. Women with permanent residence in Switzerland, those who died in Switzerland or abroad, and those who died in Switzerland but were not residing permanently in Switzerland were included in the study. To analyse the influence of maternal age on the mortality ratio four groups were formed: <25 years, 25–29 years, 30–34 years and ≥35 years.

The physician who had signed the death certificate, or the corresponding clinic, was asked to complete an anonymous questionnaire on further information on the circumstances of the deaths. This questionnaire covered personal anamnesis, family history, operations, prior pregnancies and deliveries, puerperium, mode of delivery, course of the pregnancy, fetal complications, and any available autopsy results.

Once all necessary data had been evaluated, the definitive classification of the cases into “direct”, “indirect”, “late”, and “pregnancy-independent” death was made by the three authors in accordance with the current ICD-10. Two authors (RZ and KQL) were involved in the process of classification in the previous study periods. A confidential enquiry board does not exist in Switzerland.

The direct maternal mortality ratio (MMR) was calculated by dividing the number of direct mortality cases by total number of births between 2005 and 2014. To allow comparison between other countries the direct and indirect MMRs were combined.

To assess underreporting of maternal deaths in Switzerland, the archive of the Institute of Forensic Medicine (IRM) was additionally searched for deaths in connection with pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium. The archives of the IRM were searched with the following terms: “pregnancy”, “delivery” and “childbirth”. The data were compared with the information provided by the FSO.

An important subgroup of maternal mortality after caesarean section are the deaths associated with the caesarean section, allowing calculation of the lethality of the caesarean section. For classifying the lethality of caesarean section, the death had to be temporally linked to the operation and the cause of death needed to be directly related to surgery [5]. Death was considered a direct result of caesarean section if the cause or mode of death was the direct result of surgical or anaesthetic complications.

Data on maternal mortality ratios and related causes of death in various countries were searched in the European Perinatal Health Reports, the reports of MBRRACE-UK and PubMed database. The search terms included “maternal mortality”, “maternal death” and “maternal morbidity”.

For descriptive statistical analysis we used Fisher’s exact test to calculate odds ratios (ORs).

The ethics committees of each participating canton approved this national cohort study (KEK Nr. 2016–00240).

In total, 117 maternal deaths were reported to the FSO between 2005 and 2014 (fig. 1). One additional case was found by searching the archive of the IRM. The woman in question had an accident in the early weeks of pregnancy and therefore it can be classified as a pregnancy-independent case. Fourteen cases had to be excluded as a result of lack of information because the deaths had occurred abroad. The only information given for these cases was the ICD-code R99 (Other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality) and, in 13 cases, the time that had passed since childbirth (0–331 days). One other case was excluded as the autopsy stated that the woman was not pregnant at the time of her death and had not given birth in the previous year. Seven cases had to be excluded because only ICD-10 codes and no further detailed information on the circumstances of these deaths were available (table 1). Therefore, 96 cases were eligible for a detailed analysis.

Figure 1 Flowchart: exclusion of cases.

Table 1 The seven cases excluded because lack of information made it impossible to categorise them.

| Excluded cases | Diagnosis according to ICD-10 |

Time of death

(days since delivery) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | O88.1 (Amniotic fluid embolism) O82.9 (Delivery by caesarean section, unspecified) Z94.1 (Heart transplant status) |

Unknown |

| 2 | I46.9 (Cardiac arrest, cause unspecified) | Unknown |

| 3 | I49.0 (I49.0 - Ventricular fibrillation and flutter) | 149 |

| 4 | R99. (Ill-defined and unknown cause of mortality) | 122 |

| 5 | X59.9 (Exposure to unspecified factor causing other and unspecified injury) | 165 |

| 6 | W15. (Fall from cliff) S06.9 (Unspecified intracranial injury) |

307 |

| 7 | O95. (Obstetric death of unspecified cause) | 0 |

All obstetric deaths were classified by available information in keeping with the ICD-10 classifications into “direct”, “indirect”, “late”, and “pregnancy-independent” maternal death categories (table 2). We classified 26 cases as direct obstetric deaths, 26 as indirect obstetric deaths (which included 13 suicides), 41 as non-pregnancy related and 3 as late maternal deaths. Amniotic fluid embolism and preeclampsia were classified as direct obstetric cases. Haemorrhage was classified as a direct obstetric case, except for one indirect case. Thromboembolisms were classified as direct obstetric cases, except for three cases that were classified as indirect cases. One woman had surgery for an ectopic pregnancy and received heparin postoperatively. She developed heparin induced thrombocytaemia and died as a result. In the two other cases, the women were affected by pre-existing vascular malformations, which subsequently led to thromboembolisms despite anticoagulant therapy. Two cases of infection were classified as direct deaths, and two as indirect deaths (table 3). In 13 cases, death was classified as suicide. No further information on psychological status was available.

Table 2 Classification of maternal deaths (ICD-10) and maternal mortality ratio.

| Classification | Definition | n |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal Mortality Ratio | The number of maternal deaths during a given time period per 100,000 live births during the same time period | |

| Direct obstetric deaths | Deaths resulting from obstetric complications in the pregnant state (pregnancy, labour and puerperium), from interventions, omissions, incorrect treatment, or from a chain of events resulting from any of the above | 26 |

| Indirect obstetric deaths | Deaths resulting from previously existing disease, or any disease that developed during pregnancy and was not the result of direct obstetric causes, but which was aggravated by the physiological effects of pregnancy | 26 |

| Non-pregnancy-related maternal deaths | Deaths from unrelated causes which happen to occur in pregnancy or the puerperium | 41 |

| Late maternal deaths | Deaths occurring between 42 days and 1 year after abortion, miscarriage or delivery that are due to direct or indirect maternal causes | 3 |

| Unclear | 7 | |

| Total number of maternal deaths | 103 |

Table 3 Causes of death with classification.

| Cause of death |

Total

(n) |

Direct obstetric deaths

(n) |

Indirect obstetric deaths

(n) |

Non-pregnancy-related deaths

(n) |

Unclear

(n) |

Average maternal age

(years) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemorrhage (incl. EUP) | 10 | 9 | 1 | 33.5 | ||

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 5 | 5 | 29.2 | |||

| Preeclampsia/HELLP | 5 | 5 | 35.2 | |||

| Thromboembolism | 6 | 3 | 3 | 31.5 | ||

| Infection | 4 | 2 | 2 | 33.3 | ||

| Others | 73 | 2 | 23 | 41 | 7 | 32.5 |

| Anaesthesia-related complications | 0 | |||||

| Total | 103 | 26 | 26 + 3 late maternal deaths | 41 | 7 |

EUP = extrauterine pregnancy; HELLP = haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count

Between 2005 and 2014, a total of 787,025 live births were registered in Switzerland, resulting in a direct MMR of 3.30/100,000 live births (26/787,025; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.0–4.5) during the time-period analysed. The combined MMR was 6.61/100,000 live births (OR 4.8–8.4). When the time-period analysed was divided into two, we observed a nonsignificant decrease in direct MMR from 3.99/100,000 (2005–2009: 15/375,745) to 2.67/100,000 (2010–2014: 11/411,271). Maternal mortality has decreased by 20.5% compared with that in 1995–2004 (4.15/100,000) (OR 0.8, 95% CI 0.47–1.33; p = n.s.) and by 40.4% compared with that in 1985–1994 (5.54/100,000) (OR 0.6, 95% CI 0.37–0.97; p = 0.04).

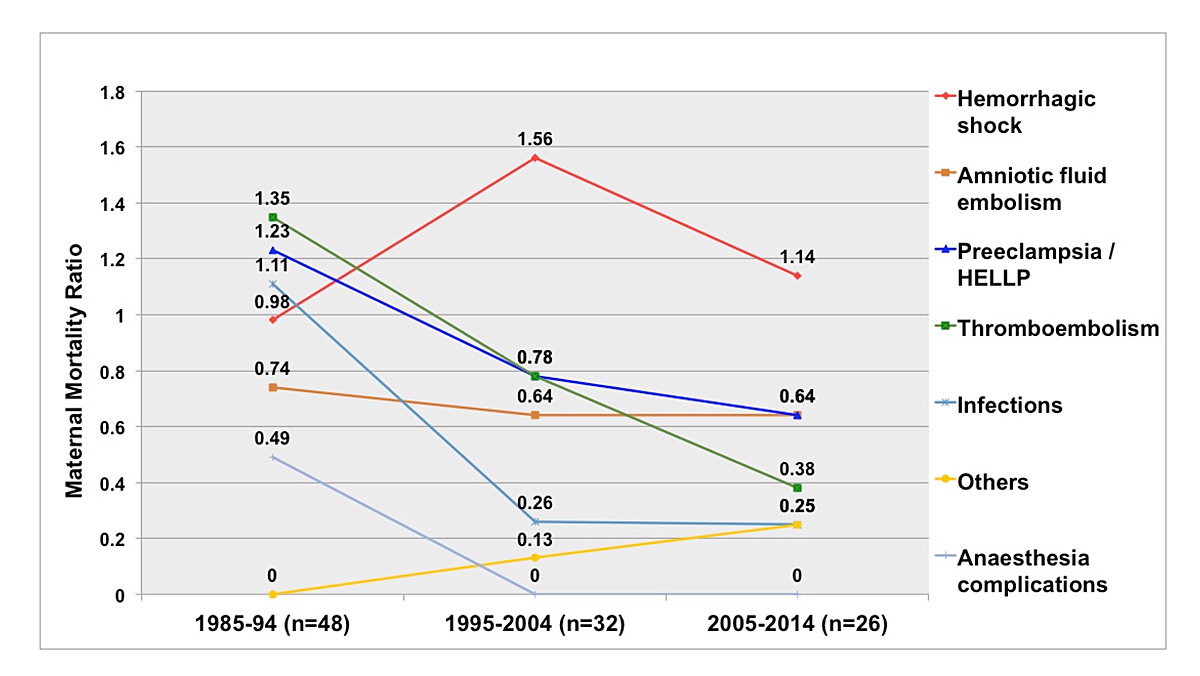

The most common cause of direct obstetric death was haemorrhage (table 3). In five cases, the women died because of uterine atony. Two women died of ectopic pregnancy, and two women died in relation to a ruptured uterus. One woman suffered from severe vaginal bleeding and died of a myocardial infarction. Compared with the previous study period, Swiss maternal mortality due to haemorrhage reduced by almost 27% (1995–2004: 1.56/100,000 live births vs 2005–2014: 1.14/100,000 live births) [4] (fig. 2). However, comparison of the study period of 1995–2004 with the first study period of 1985–1994 showed an increase of 59.2% [3]. Both comparisons were not statistically significant. Since that increase, a reduction in maternal mortality due to haemorrhage has occurred (fig. 2). Although overall mortality has reduced in the last 30 years, the number of women dying as a result of haemorrhage still accounts for roughly 35% of all direct maternal deaths (table 4).

Figure 2 Direct maternal mortality in Switzerland 1985–2014 per 100,000 live births, separated by cause of death.

Table 4 Direct maternal mortality in Switzerland 1985–2014.

| . |

1985–1994

(n = 48) n (%) mortality per 100,000 live births |

1995–2004

(n = 32) n (%) mortality per 100,000 live births |

2005–2014

(n = 26) n (%) mortality per 100,000 live births |

2005–2014

including suicides (n = 39) n (%) mortality per 100,000 live births |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemorrhage (incl. EUP) | 8 (16.6) 0.98 |

12 (37.5) 1.56 |

9 (34.6) 1.14 |

9 (23.1) 1.14 |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 6 (12.5) 0.74 |

5 (15.6) 0.64 |

5 (19.2) 0.64 |

5 (12.8) 0.64 |

| Preeclampsia/HELLP | 10 (20.8) 1.23 |

6 (18.8) 0.78 |

5 (19.2) 0.64 |

5 (12.8) 0.64 |

| Thromboembolism | 11 (22.9) 1.35 |

6 (18.8) 0.78 |

3 (11.5) 0.38 |

3 (7.7) 0.38 |

| Infection | 9 (18.8) 1.11 |

2 (6.3) 0.26 |

2 (7.7) 0.25 |

2 (5.1) 0.25 |

| Others | 0 0 |

1 (3) 0.13 |

2 (7.7) 0.25 |

2 (5.1) 0.25 |

| Anaesthesia-related complications | 4 (8.3) 0.49 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

0 0 |

| Suicides | 13 (33.3) 1.65 |

EUP = extrauterine pregnancy; HELLP = haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count

The second leading causes of direct obstetric deaths were amniotic fluid embolism and HELLP syndrome (haemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count) / preeclampsia. In all preeclampsia cases, there was no information available on risk factors (e.g., history of preeclampsia) and, hence, aspirin received as prophylaxis. Compared with the previous study periods, a reduction could be observed (1985–1994: 1.23/100,000 live births vs 2005–2014: 0.64/100,000 live births, p = n.s.) [3, 4].

For the rates of amniotic fluid embolism, a reduction from the first to the second study period (0.74/100,000 to 0.64/100,000 live births) was observed, but no further decline in the amniotic fluid embolism rate since 2004 was observed [3, 4].

The third most common cause of direct obstetric death was thromboembolism (0.38/100,000 live births), accounting for almost 12% of all direct maternal deaths. In one indirect case, the woman had surgery for an ectopic pregnancy, developed heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and later died of thromboembolism. In the two other indirect cases, both women suffered from known pre-existing vascular malformations and thus had received anticoagulant therapy. In all three direct obstetric death cases, however, insufficient information was available to determine if the women had any risk factors that would have needed anticoagulant prophylaxis. Compared with previous study periods, the number of deaths due to thromboembolism decreased (1985–1994: 1.35/100,000 [OR 0.28, 95% CI 0.08–1.0; p = 0.05] to 1995–2004: 0.78/100,000 live births [OR 0.49, 95% CI 0.12–1.96; p = n.s.,]) [3, 4].

Infection was the least common cause for direct obstetric death during this study period (0.26/100,000 live births). Compared with the first study period, infection as the cause of death became much less prevalent (fig. 2). A nonsignificant decrease in MMR due to infection was observed between the first and the second study periods (1985–1994: 1.1/100,000 live births, 1995–2004: 0.26/100,000) and has been unchanged since then [3, 4].

In the study period of 1985–1994, maternal mortality due to anaesthesia-related complications amounted to 0.5/100,000 live births [3]. Since then, no maternal deaths due to such complications have been recorded in Switzerland.

The indirect MMR was 3.68/100,000 live births. In the current study, 13 women committed suicide. All suicides were classified as indirect deaths. There was not enough information about the mental health history of these women to classify them as either direct deaths or non-pregnancy-related deaths. The median age of the women who committed suicide was 36.7 years. In the general Swiss population from 2012 to 2016, the suicide rate of women aged 15–44 years (including pregnant and postpartum women) was 3.6/100,000 females [6]. The suicide rate in relation to pregnancy and delivery was 1.65/100,000 live births. In the previous study period, there were two non-pregnancy-related suicides [4].

However, if all suicides had been classified as direct obstetric deaths in accordance with ICD-MM, then suicides would have been the leading cause of maternal deaths in Switzerland (table 4) and the direct MMR would be 5.0/100,000 live births.

A total of 41 non-pregnancy related deaths were analysed. Twenty women died owing to a tumour (one neurological, two respiratory, six gastrointestinal, three urological/gynaecological, three melanoma, five others), seven died because of an accident and seven women were murdered. The seven remaining women were classified as “others”. Three deaths were classified as “late” maternal deaths as they occurred more than 42 days after delivery. All of them were classified as indirect obstetric deaths and not included in the direct MMR.

Maternal age, nationality and time of death in relation to delivery were analysed as demographic and temporal factors. The mean maternal age at death was 33.2 years (range 19–51). The risk for maternal mortality was significantly higher for women older than 35 years (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.14–3.53) (table 5). In the study period of 1985–1994, the mean maternal age at death was 30.7 years, demonstrating the trend of rising maternal age in Switzerland [3, 7]. In 2015, 31.2% of all women with live births in Switzerland were 35 years or older [8].

Table 5 Maternal mortality by maternal age in Switzerland 2005–2014.

| Maternal age (years) | Maternal deaths (direct) | Live births |

Maternal mortality/

100,000 live births |

Direct maternal mortality /100,000 live births | All cases: odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | Direct cases: odds ratio (95% confidence interval) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <25 | 8 (3) | 73,728 | 10.9 | 4.1 | 1.24 (0.54–2.88) |

1.58 (0.38–6.62) |

| 25–29 | 17 (5) | 194,422 | 8.7 | 2.6 | 1 (ref.) | 1 (ref.) |

| 30–34 | 31 (8) | 290,383 | 10.7 | 2.8 | 1.22 (0.67–2.21) |

1.07 (0.35–3.27) |

| ≥35 | 40 (10) | 228,492 | 17.5 | 4.4 | 2.0 (1.14–3.53) |

1.7 (0.58–4.99) |

| Total | 96 (26) | 787,025 | 12.2 | 3.3 |

Among the 96 analysed cases, 60 women were of unknown nationality. As more than two thirds were of unknown nationality, the influence of nationality was not evaluated.

In 16 cases, death occurred during pregnancy. In one case, the time of death could not be determined. Among the 79 remaining women, 8 had spontaneous vaginal deliveries, 5 had vaginal operative deliveries and 24 had caesarean sections. In 42 cases, the mode of delivery was not known. This included one direct, one indirect, all 11 postpartum suicides and 29 non-pregnancy-related deaths. In the group of 26 direct obstetric deaths, 5 women died during pregnancy, 20 women gave birth and in 1 case it was not clear at which point death had occurred. Among the 20 women that gave birth, 7 had spontaneous vaginal deliveries, 3 had vaginal operative deliveries, 9 had caesarean sections, and in 1 case it was not known how the woman had delivered. An autopsy was available for 25% of all registered cases (26 out of 102).

To assess underreporting, the cases reported by the FSO that occurred in the canton of Zurich were compared with the cases in the archive of the IRM at the University of Zurich. In total, 149,601 live births were registered between 2005 and 2014 in the canton of Zurich, and eight deaths (four direct cases, four unrelated deaths) were reported by the FSO, resulting in a direct maternal mortality ratio of 2.67/100,000 live births. When we searched the archives, one additional indirect maternal death was discovered. Although this had no effect on the direct maternal mortality ratio, the rate of underreporting for all maternal mortality cases was 11.1%.

All maternal deaths that were temporally correlated with a caesarean section were included in the calculation of mortality after caesarean section, independent of the cause of death. Between 2005 and 2014, 29.4% of all 787,025 live births in Switzerland occurred by caesarean section, which results in 231,385 live births by caesarean section. In the current study, 79 women gave birth, among whom 24 (30.4%) had caesarean sections, but the delivery mode was unknown in 42 cases. Therefore, the MMR after caesarean section was 0.01%.

In the current study, two cases were found in which a direct link to caesarean section seemed plausible and thus were used for the calculation of the lethality of a caesarean section. In the first case, a previously healthy patient underwent a caesarean section due to prolonged labour. On the first postoperative day she complained of shortness of breath and her general state deteriorated. No sign of bleeding could be found in the re-laparotomy, but postoperatively the patient suffered a fatal cardiac arrest and the autopsy revealed that the cause of death was an amniotic fluid embolism. In the second case, a women had a spontaneous, uneventful twin gestation and an elective caesarean section at 38 weeks gestation. The patient had a massive postpartum haemorrhage due to atonic uterus, unsuccessful administration of uterotonics and, despite an emergency hysterectomy, she died as a result of hypovolaemic shock (table 6). In all other direct cases, caesarean sections were due to pre-existing pregnancy-related diseases or conditions that were further aggravated during pregnancy: preeclampsia/HELLP (n = 3) and placental abruption (n = 2). The lethality after caesarean section was 0.0086‰ (2/231,385). In the two earlier studies, the lethality after caesarean section was 0.02‰ (1995–2004) and 0.09‰ (1985–1994), resulting in a reduction of 57% (p = n.s.) and 90% (OR 0.09, p<0.05, 95% CI 0.02–0.42), respectively [3, 4].

Table 6 Cause of death in relation to caesarean section (vaginal deliveries = 67.9% of 787,007 live births).

| Cause of death | Caesarean section | Vaginal delivery (direct cases) | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemorrhage | 1/252,979 | 3/607,110 | 0.8 | 0.08–7.69 | n.s. |

| Embolism | 1/252,979 | 3/607,110 | 0.8 | 0.08–7.69 | n.s. |

According to the EURO-PERISTAT report published in 2013, the MMR ranged from under 3 per 100,000 live births (Greece, Iceland, Finland, Poland) to over 12 per 100,000 live births (Hungary, Romania, Latvia) in Europe [6]. The most common direct obstetric cause of death in Europe was haemorrhage (15% of maternal deaths, 0.87/100,000 live births), followed by preeclampsia/HELLP (12%, 0.72/100,000 live births) between 2006 and 2010 [9]. As the third most common cause of death, “deaths due to first-trimester complications” (e.g., ectopic pregnancies and abortions) were registered, unlike the scenario in 2004 when thromboembolism and amniotic fluid embolism were more common. This sudden surge in deaths due to first-trimester complications was a direct cause of the high number of maternal deaths after abortions in Romania. Compared with the maternal mortality ratio of other European countries described in the EURO-PERISTAT report published in 2018, Switzerland has one of the lowest rates in Europe [10].

In the current study, as many as 30.8% of all indirect maternal deaths were a result of a cardiac pathology. More than half (62.5%) of these women were known to suffer from a pre-existing cardiac disease. In the USA, cardiovascular disease has become the leading cause of maternal death, as it accounts for almost 4.23 deaths per 100,000 live births [11, 12]. In the UK, the incidence of heart disease during pregnancy has remained constant at about 0.9%, but the rate of maternal deaths due to cardiac disease has increased progressively in the last 20 years [13], accounting for a maternal mortality ratio of 2.18 per 100,000 maternities from 2012 to 2014 [14].

As previously stated almost a third (31.2%) of all women who gave birth in Switzerland in 2015 were above the age of 35 [8]. An even higher proportion was observed in Ireland (34.3%), Italy (36.3%) and Spain (37.3%), with the median percentage in Europe being 20.8% [10].

As nationality was unknown in the majority of the analysed cases, it was not evaluated in this study. According to the EURO-PERISTAT report in 2010, compared with other European countries, Switzerland had the second highest percentage (41.1%) of mothers who were born abroad, being surpassed only by Luxembourg with 66% [9].

The direct maternal mortality ratio in the 10-year period between 2005 and 2014 was at least 3.30/100,000 live births in Switzerland. This represents a non-significant reduction of the direct maternal mortality ratio by 20.5% compared with the previous 10-year period. When the combined MMR (6.61/100,000), as described in the EURO-PERISTAT report, was compared with those of other European countries Switzerland had an MMR in the middle range [10].

If the suicide cases are included in the direct mortality, the ratio would be 5.0/100,000 live births (table 4). Poor mental health during pregnancy or following delivery can have severe implications for maternal mortality. Psychiatric disorders, followed by suicide, have been identified in the UK as an emerging cause of maternal deaths [14]. In the case of suicide, it is challenging to differentiate between a coincidental and non-pregnancy-related or any indirect or direct maternal death. In order to reduce underreporting, the WHO introduced in 2012 the International Classification of Disease for Maternal Mortality (ICD-MM), in which all suicides during pregnancy and up to a year after the birth are to be classified as direct obstetric deaths [15]. As information regarding the mental health history of the women in this study who committed suicide was limited, these deaths were not classified as direct obstetric deaths, but instead were classified as indirect deaths. This also allowed a direct comparison with the previous study periods. However, the direct maternal mortality ratio was also calculated with the suicides included to evaluate the new trend of classifying them as direct cases (table 4). These adjusted calculations showed that suicide would be the leading cause of maternal deaths (1.65/100,000 births) in Switzerland, reflecting the global trend [16].

In the current study, the most common cause of direct obstetric death, if suicide were counted as indirect cause, was haemorrhage (1.14/100,000 live births). Compared with the previous study period (1995–2004), a reduction in maternal mortality due to haemorrhage has been achieved. Nonetheless, compared with the study period of 1985–1994 (0.98/100,000 live births), maternal mortality has actually risen (fig. 2). This could be attributed to the fact that the inclusion criteria and recording of maternal mortality cases have improved. However, immediate action is still needed to further reduce the rate of haemorrhage that leads to maternal deaths. The Swiss Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (SGGG) notes that in most situations action taken was too little and too late, with an unfavourable outcome [17]. Solely relying on the visual assessment of blood loss is insufficient as it is underestimated routinely by 30–50% [18]. All postpartum haemorrhage cases should be subject to critical review. According to the MBRRACE-UK report, obstetricians need to pay special attention to women who are at risk for abnormal placentation and plan accordingly for their delivery to further reduce the rate of maternal deaths due to haemorrhage [19].

Together with amniotic fluid embolism, preeclampsia/HELLP was found to be the second leading cause of maternal mortality in Switzerland, each accounting for almost 20% of all direct obstetric deaths (0.64/100,000 live births). When the current results were compared with the previous study periods, a reduction was observed in each decade as the detection and management of these disorders improves. In the UK also, the maternal mortality ratio due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy has significantly decreased [14]. In 2009–2011 and 2012–14, the ratio decreased from 0.42 to 0.11/100,000 live births. Despite this reduction, after examining each individual case, the assessors of MBRRACE-UK felt that improvements in care might have made a difference in the outcome in 93% of cases [14].

Reported risk factors for amniotic fluid embolisms include operative delivery (vaginal or caesarean), placenta praevia, placenta accreta and abruption, since in these situations an exchange of fluids between the maternal and fetal compartments is more likely [20]. In the last 30 years, a slight reduction in amniotic fluid embolism from the first to the second study period was observed (fig. 2).

In this study, maternal death due to thromboembolism was the third most common cause of death (0.38/100,000 live births). Pregnant women are five times more likely to develop venous thromboembolism than those who are not pregnant and therefore are at a higher risk for pulmonary embolism [21]. The risk is particularly high during the postpartum period [22]. Although maternal mortality due to thromboembolism has steadily decreased in the last 30 years in Switzerland, it is still an important cause of maternal deaths and thus risk assessment for venous thromboembolism is vital [14].

Circulatory diseases account for a high number of indirect obstetric causes of deaths in Europe [10]. This increase can be attributed to rising numbers of women with heart disease and is likely to rise as the mean maternal age and obesity rates increase [13]. In the case of a pre-existing condition, a cardiologist must assess the effect of pregnancy on the condition and the accompanying risk for mother and fetus.

The average maternal age of women giving birth has steadily increased over the years. Compared with other European countries, Switzerland has a high proportion of women aged 35 years and above [10]. As observed in the current study, this group of women is at a higher risk for perinatal mortality (table 5). Increasing maternal age is a known risk factor for adverse outcomes in obstetrics, since it is often associated with other morbidities that are becoming more common in the childbearing population [12].

Maternal mortality serves as a marker of the performance of the healthcare system and even of prevailing social inequalities. Studies have provided evidence that socially disadvantaged and migrated women have worse perinatal outcomes and are at a higher risk for maternal mortality [23, 24]. The current study did not analyse the distribution of nationalities because of limited data on nationality.

Although the mode of delivery was unknown in 42 cases, more than two thirds of those cases were non-pregnancy-related deaths. When comparing the frequency of embolism and haemorrhage after caesarean section versus vaginal delivery in all available cases, we did not find a difference (table 6).

Since 2007, the FSO links birth data with the date of death of the mother, thus allowing women who had given birth in the year before their death to be identified. Therefore, cases where death occurred within 365 days after delivery were included as well. Due to improved monitoring strategies, an increase in maternal mortality was expected. There was an overall increase in the number of maternal deaths analysed, as well as an increase in the number of indirect cases; however, an increase in direct maternal mortality was not observed. This is likely owing to improved clinical care, as well as to the fact that a large proportion of the additionally analysed deaths were non-pregnancy-related maternal deaths.

There are several limitations to address in this study. The questionnaires sent to the involved clinics were usually filled out by physicians who were not involved in the analysed case. So, they were either not able or not willing to give a detailed report of the incident. This made it more challenging to categorise some cases. When contacting the clinics in question, we usually could not obtain much more information, which would have helped us categorise these cases, thus forcing us to exclude seven cases. In one case, information was not provided as it was subject to an ongoing legal case.

Additionally, autopsy reports were available in only 25% of all cases. Maternal deaths should be considered “unexpected death” and therefore undergo autopsy. An in-depth questionnaire sent to the clinic that filled out the death certificate immediately after the registration of such deaths could improve the quality of data.

A further limitation was the small numbers used for analysis as a result of missing data (e.g., mode of delivery), which made it difficult to obtain statistically significant results. In general, the documentation of fatal cases involving women should be improved by investigating previous pregnancies and deliveries. Another difficulty was the classification of deaths according to ICD-10 as opposed to ICD-MM, which was introduced in 2012. Since one of the main outcomes was to draw a comparison between this study and its preceding studies, where this practice was not yet in place, we decided to classify by ICD-10. However, this made comparison with neighbouring countries more difficult.

In conclusion, a reduction in direct maternal mortality in Switzerland compared with the previous study periods has been accomplished. This is a result of the reduced rates of hypertensive disorders, thromboembolism, infections and anaesthesia-related complications. Although a reduction in maternal mortality due to haemorrhage compared to the previous study periods has been achieved, the incidence is still too high and further action is needed in this regard. An alarmingly high percentage of women committed suicide, and thus future studies and interventions should focus on the prevention of suicides. This study should also raise awareness of the need for precise documentation of all maternal deaths in a reasonable time-window after the woman has passed away. Only if documentation is complete, can the classification be as precise as possible. In the light of quality assurance, the knowledge gained from this kind of study can improve the pregnancy outcome of future mothers.

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We would like to thank all the doctors in the different hospitals or other medical settings that helped to gather the information on individual cases. Particularly, we would like to thank Prof. Michael J. Thali and Dr Sebastian Eggert from the Institute of Forensic Medicine at the University of Zurich for their support in their archives.

1 Alkema L , Chou D , Hogan D , Zhang S , Moller A-B , Gemmill A , et al.; United Nations Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group collaborators and technical advisory group. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016;387(10017):462–74. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00838-7

2World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western P. Sustainable development goals (SDGs): Goal 3. Target 3.1: By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births [poster]. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2016.

3 Meili G , Huch R , Huch A , Zimmermann R . Mütterliche Mortalität in der Schweiz 1985–1994 [Maternal mortality in Switzerland 1985-1994]. Gynakol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch. 2003;43(3):158–65. Article in German. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1159/000070795

4 Fässler M , Zimmermann R , QuackLötscher KC . Maternal mortality in Switzerland 1995-2004. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(1-2):25–30. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2010.12768

5 Kallianidis AF , Schutte JM , van Roosmalen J , van den Akker T ; Maternal Mortality and Severe Morbidity Audit Committee of the Netherlands Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology. Maternal mortality after cesarean section in the Netherlands. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;229:148–52. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.08.586

6Bundesamt für Statistik. Suizid nach Alter und Geschlecht (ohne assistierten Suizid) - 1995-2016 | Diagramm. 2018. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/aktuell/neue-veroeffentlichungen.assetdetail.11348164.html.

7Bundesamt für Statistik. Lebendgeburten nach Alter der Mutter 2018. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home.assetdetail.13187342.html.

8Bundesamt für Statistik. Lebendgeburten nach Alter der Mutter und Kanton 2015. 2018. Available from: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/bevoelkerung/geburten-todesfaelle/geburten.html.

9EURO-PERISTAT Project with SCPE and EUROCAT. European Perinatal Health Report 2010 - Health and Care of Pregnant Women and Babies in Europe in 2010. May 2013. Available from: www.europeristat.com.

10EURO-PERISTAT Project, European Perinatal Health Report. Core Indicators of the Health and Care of Pregnant Women and Babies in Europe in 2015. November 2018. Available from: www.europeristat.com.

11 Moussa HN , Rajapreyar I . ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 212: Pregnancy and Heart Disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2019;134(4):881–2. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000003497

12 Creanga AA , Berg CJ , Syverson C , Seed K , Bruce FC , Callaghan WM . Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(1):5–12. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000564

13 Zöllner J , Curry R , Johnson M . The contribution of heart disease to maternal mortality. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2013;25(2):91–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/GCO.0b013e32835e0f11

14Knight MNM, Tuffnell D, Kenyon S, Shakespeare J, Brocklehurst P, Kurinczuk JJ, eds. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care: Surveillance of Maternal Deaths in the UK 2012–14 and Lessons Learned to Inform Maternity Care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2009–14. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2016.

15World Health Organisation. The WHO application of ICD-10 to deaths during pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium: ICD MM. WHO. 2016.

16 Mangla K , Hoffman MC , Trumpff C , O’Grady S , Monk C . Maternal self-harm deaths: an unrecognized and preventable outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(4):295–303. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2019.02.056

17Surbek D, Hess T, Drack G. Expertenbriefe Nr. 26 - Aktuelle Therapieoptionen der postpartalen Hämorrhagie. Schweizerische Gesellschaft für Gynäkologie und Geburtshilfe (SGGG). 2019.

18 Main EK , Goffman D , Scavone BM , Low LK , Bingham D , Fontaine PL , et al.; National Parternship for Maternal Safety; Council for Patient Safety in Women’s Health Care. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: consensus bundle on obstetric hemorrhage. Anesth Analg. 2015;126(1):155–62. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000000869

19Knight MBK, Tuffnell D, Jayakody H, Shakespeare J, Kotnis R, Kenyon S, et al., eds. on behalf of MBRRACE-UK. Saving Lives, Improving Mothers’ Care - Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2014-16. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford, 2018.

20 Clark SL , Hankins GD , Dudley DA , Dildy GA , Porter TF . Amniotic fluid embolism: analysis of the national registry. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172(4 Pt 1):1158–67, discussion 1167–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(95)91474-9

21 Devis P , Knuttinen MG . Deep venous thrombosis in pregnancy: incidence, pathogenesis and endovascular management. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7(S3, Suppl 3):S309–19. doi:.https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2017.10.08

22 Heit JA , Kobbervig CE , James AH , Petterson TM , Bailey KR , Melton LJ, 3rd . Trends in the incidence of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy or postpartum: a 30-year population-based study. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(10):697–706. doi:.https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-143-10-200511150-00006

23 Pedersen GS , Grøntved A , Mortensen LH , Andersen AM , Rich-Edwards J . Maternal mortality among migrants in Western Europe: a meta-analysis. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18(7):1628–38. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-013-1403-x

24 Heslehurst N , Brown H , Pemu A , Coleman H , Rankin J . Perinatal health outcomes and care among asylum seekers and refugees: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):89. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1064-0

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.