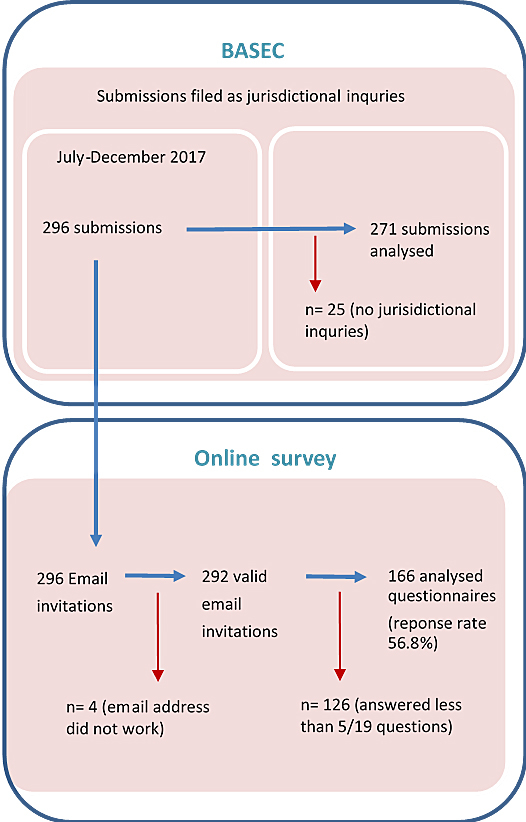

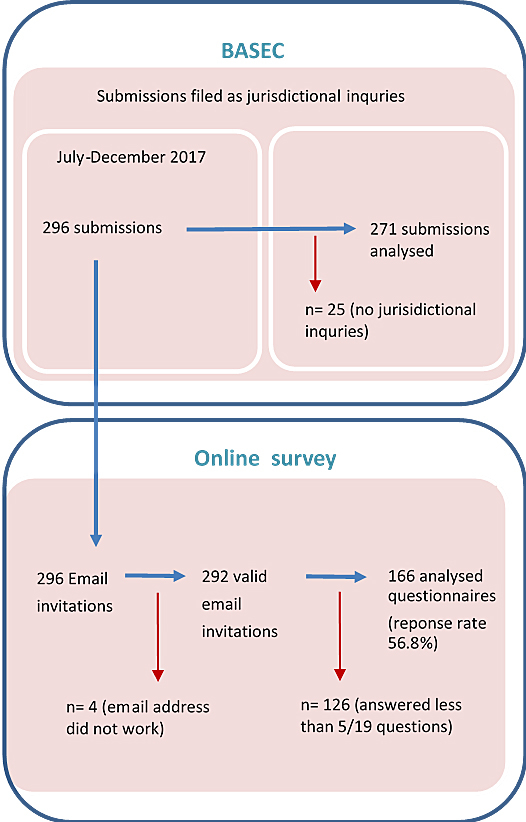

Figure 1 Definitions of the analysis sets for (a) the qualitative review of jurisdictional inquiries and (b) the quantitative survey of submitting researchers.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20318

Ethical oversight systems have been developed around the world with the aim of protecting research participants from unjustified risks and abuse [1]. Researchers wanting to conduct “research” involving human beings are typically required to obtain prior approval from an independent ethics committee [2, 3]. As there often does not exist an equivalent oversight process for “non-research”, the decision whether or not a project constitutes “research” under current regulations plays a crucial role in determining the level of ethical oversight it receives [3, 4]. A number of projects in the healthcare setting, however, occupy a grey zone where “research” cannot always be clearly differentiated from “non-research” [5–7]. International research has highlighted how this situation can lead to persistent difficulties in determining whether certain projects need to be submitted to a research ethics committee [5, 8]. Controversies, such as the widely discussed Keystone study [9–13], indicate that this uncertainty also runs the risk of the ethical oversight system itself undermining efforts to improve patient care by making these projects unduly burdensome to conduct. It is therefore important that processes exist to help clarify the need for ethical approval.

In Switzerland, medical research became comprehensively regulated for the first time at the federal level in 2014 with the implementation of the Federal Act on Research involving Human Beings (Human Research Act). At the same time, research ethics committees were also reorganised or merged into seven committees, and swissethics, the umbrella organisation of Swiss research ethics committees, was created to support standardisation [14]. The Human Research Act has two main related ordinances, the Ordinance on Human Research with the Exception of Clinical Trials (Human Research Ordinance) and the Ordinance on Clinical Trials in Human Research (Clinical Trials Ordinance). Pursuant to article 2 of the Human Research Act, the Act only applies to research “concerning human diseases and concerning the structure and function of the human body”. Article 3 of the Act defines “research” to mean a “method-driven search for generalisable knowledge”. Whereas research involving non-anonymised health data or non-anonymised biological material is required to obtain approval by a research ethics committee, the Human Research Act does not apply to research involving anonymously collected health-related personal data, anonymised health-related personal data, or anonymised biological material (article 2).

Swiss researchers can contact the responsible research ethics committee via a jurisdictional inquiry for clarification whether a project needs to be submitted for ethics approval. If the research ethics committee determines that the activity is not “research” for the purposes of the Human Research Act, the committee will send a letter to researchers confirming that the project is not covered by the Act and therefore falls outside of the committee’s competency. Researchers have also been able to request a statement from the research ethics committee that it has no objections to projects that are not covered by the Human Research Act. There has not been, however, research on the underlying reasons for jurisdictional inquiries in Switzerland, and we are not aware of research on similar requests in other countries.

The Federal Office of Public Health is responsible for evaluating the implementation of the Human Research Act. Based on the findings of this evaluation, the Federal Council can then decide on any further steps, such as revising the law [15]. As a part of this evaluation process, the Federal Office of Public Health and swissethics wanted to better understand the reasons for jurisdictional inquiries. This exploratory mixed-methods research was therefore conducted during the evaluation period with the aim of (1) examining the characteristics of jurisdictional inquiries to Swiss research ethics committees, and (2) identifying possible uncertainties regarding the correct interpretation of existing legislation in Switzerland.

This article is reported according to the Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) as described in the supplementary material (appendix 1) and related to a detailed report commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health and swissethics.

All jurisdictional inquiries submitted through the swissethics’ central online submission system (Business Administration System for Ethics – BASEC) between July and December 2017 were included in the qualitative analysis. This timeframe was used because all researchers in Switzerland have been required to use this central online submission system since July 2017. All jurisdictional inquiries are therefore submitted to BASEC before being forwarded to the responsible research ethics committee for assessment. Due to time constraints of the project, it was also not feasible to include jurisdictional inquires after December 2017.

In early January 2018, swissethics provided the project team with a distinct set of BASEC data, exported into an Excel file, regarding the jurisdictional inquiries. This included information about the general purpose of the inquiry, the type of research project, the outcome of the inquiry, and email correspondence between researchers and research ethics committees. All received information was treated confidentially by the research team.

The data were analysed using qualitative content analysis [16, 17]. All available information in BASEC was considered, including study protocols, emails, the standard form labelled “brief description of the project” and cover letter. VG initially coded 50 jurisdictional inquiries and constructed a preliminary coding framework, which was then checked and discussed with MB and BL. For the remaining inquiries, VG extracted the relevant data into an Excel file, checked whether the existing coding framework already described the relevant issues and introduced new categories where necessary. VG integrated the findings and the results were discussed during an in-person meeting, where any remaining coding problems were resolved by consensus or discussion. The final coding framework was checked by all authors to ensure consistency and validity.

An online survey was conducted between June and July 2018, using Sphinx Online Manager (Le Sphinx Développement 2015). On 6 June 2018, all 296 researchers who submitted a jurisdictional inquiry between July and December 2017 received a personalised email invitation to participate in the survey in the language (German, French, or Italian) used by the responsible research ethics committee. Four email addresses did not work, leaving 292 valid email invitations (fig. 1). A link to the online survey in English was provided in the email. Three reminders were sent to non-responders up to 17 July 2018.

Figure 1 Definitions of the analysis sets for (a) the qualitative review of jurisdictional inquiries and (b) the quantitative survey of submitting researchers.

We developed survey questions based on discussions within our research team (including representatives of swissethics and the Federal Office of Public Health). Survey questions explored respondents’ role in the project, research experience, the perception of the submission process through BASEC and whether the project was started after the reply of the research ethics committee to the jurisdictional inquiry (see appendix 1). The survey took approximately 10 minutes to complete.

Descriptive statistics included means for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. The nature of our analyses was exploratory. Data management and descriptive analyses were performed using STATA version 13.0.

The researchers who carried out the study and analysis have diverse disciplinary backgrounds and training, such as medicine/clinical epidemiology (MB, EvE), nutrition/health technology assessment/clinical epidemiology (VG), medicine or biology/human research regulation (SD, BH, PG, MR, BL, BM) qualitative research/biomedical ethics (SM), statistics/bioinformatics (PB) and survey implementation (IG). All researchers worked together as a team and extensively discussed the data interpretation to minimise bias. None of us knew any of the included research projects before.

Between July and December 2017, a total of 296 inquiries were submitted as “jurisdictional inquiries” on swissethics’ central online submission system. The responsible research ethics committees for the majority (235/296; 79.4%) of jurisdictional inquiries were Zurich (112/296; 37.8%), Bern (72/296; 24.3%), and Northwest and Central Switzerland (51/296; 17.2%). The remaining jurisdictional inquiries were forwarded to the research ethics committees of Vaud (23/296; 7.8%), Geneva (20/296; 6.8%), East Switzerland (16/296; 5.4%) and Ticino (2/296; 0.7%).

Analysis identified three groups of requests submitted as “jurisdictional inquiries”:

In addition, 8.4% (25/296) of the submissions concerned such things as communication of protocol deviations or amendments, which should have been submitted through other channels. These are not jurisdictional inquires and were therefore excluded from further analysis. The review therefore consisted of 271 jurisdictional inquiries.

Of the 271 jurisdictional inquiries included, the vast majority were in German (149/271; 54.9%) or English (94/271; 34.7). The jurisdictional inquiries most frequently concerned observational studies (117/271; 43.2%) and included persons as subjects (178/271; 65.7%) (table 1).

Table 1 Characteristics of the jurisdictional inquiries included.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 271) |

|---|---|

| Language | |

| German | 149/271 (54.9%) |

| English | 94/271 (34.7%) |

| French | 27/271 (9.9%) |

| Italian | 1/271 (0.4%) |

| Study design | |

| Observational study | 117/271 (43.2%) |

| Qualitative study | 47/271 (17.3%) |

| Method validation study | 27/271 (10%) |

| Basic research | 20/271 (7.4%) |

| Diagnostic accuracy study | 14/271 (5.2%) |

| User testing | 14/271 (5.2%) |

| Case report/series | 9/271 (3.3%) |

| Randomised controlled trial | 7/271 (2.6%) |

| Patient registry | 4/271 (1.5%) |

| Education programme | 3/271 (1.1%) |

| Feasibility study | 3/271 (1.1%) |

| Experimental computer model | 1/271 (0.4%) |

| Experimental robotics research | 1/271 (0.4%) |

| Noise emission study | 1/271 (0.4%) |

| No information | 1/271 (0.4%) |

| Subject type | |

| Persons | 178/271 (65.7%) |

| Already collected personal data | 71/271 (26.2%) |

| Already collected biological material | 6/271 (2.2%) |

| Study conducted exclusively abroad | 4/271 (1.5%) |

| Deceased persons | 2/271 (0.7%) |

| Other | 9/271 (3.5%) |

| No information | 1/271 (0.4%) |

To identify possible uncertainties regarding the correct interpretation of the Human Research Act, qualitative analysis focused on the 218 jurisdictional inquiries requesting clarification whether the project had to be submitted for ethical approval. Analysis identified eight distinct legal issues that appeared to be the main cause for a number of jurisdictional inquiries (table 2). The two most frequently identified issues were whether the project constituted “research” that will produce generalisable knowledge as defined under article 3a of the Human Research Act (59/218; 27%) and whether the project used “anonymised biological material or health-related data” as defined under article 3i of the Human Research Act.

Table 2 Legal issues causing uncertainty.

| Legal issue causing uncertainty | Total (N = 218) |

|---|---|

| 1. If the project constitutes “research” that will produce generalisable knowledge | 59/218 (27.1%) |

| 2. If the project uses “anonymised biological material or health-related data” | 43/218 (19.7%) |

| 3. If the project uses “health-related personal data” | 22/218 (10.1%) |

| 4. If the project falls under the scope of the Human Research Act | 22/218 (10.1%) |

| 5. If informed consent is required | 11/218 (5.1%) |

| 6. If the research project is a clinical trial | 10/218 (4.6%) |

| 7. How to import or export biological material, genetic data or other health-related data | 3/218 (1.4%) |

| 8. The further use of data, samples of an ongoing research project | 2/218 (0.9%) |

| Other reasons for the inquiry | 46 (21.2%) |

Overall, research ethics committees decided that 78.6% (213/271) of the jurisdictional inquiries were outside their jurisdiction and did not require ethical approval, 15.6% (42/271) required submission for ethical approval and 4.4% (12/271) required further information; for 1.5% (4/271) of the jurisdictional inquiries, no outcome was available (table 3). However, jurisdictional inquiries requesting a declaration of no objection (46/50; 92%) were determined to be outside the jurisdiction of the research ethics committee more often than inquiries clarifying the need for ethical approval (165/218; 75.7%). Conversely, jurisdictional inquiries clarifying the need for ethical approval (39/218; 17.9%) were determined to require ethical approval more frequently than inquiries requesting a declaration of no objection (2/50; 4%).

Table 3 Outcome of the jurisdictional inquiries.

| Outcome | Type of jurisdictional inquiry | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Need for ethical approval

(n = 218) |

Declaration of no objection request (n = 50) |

Applicable ordinance

(n = 3) |

Total

(N = 271) |

|

| Outside jurisdiction | 165/218 (75.7%) | 46/50 (92%) | 2/3 (66.7%) | 213/271 (78.6%) |

| Submission required | 39/218 (17.9%) | 2/50 (4%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | 42/271 (15.5%) |

| Further information requested | 11/218 (5%) | 1/50 (2%) | 0 | 12/271 (4.4%) |

| No outcome available | 3/218 (1.4%) | 1/50 (2%) | 0 | 4/271 (1.5%) |

Between June 2018 and July 2018, 178 responses to the online survey were received. However, 12 respondents answered fewer than 5 of the 19 survey questions and were therefore excluded from analysis. Consequently, the online survey achieved a 56.8% (166/292) response rate (see fig. 1). Respondents had an average age of 40.9 years (range 39.2–42.5), and 52.4% of respondents were female (87/166). The majority of respondents (104/166; 62.7%) worked in a university or university hospital, were a non-medical or medical researcher (102/166; 61.4%), and had experience in research for an average of 9.9 years (range 8.5–11.3 years) (table 4).

Table 4 Characteristics of survey respondents.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 166) |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (range) | 40.9 (39.2–42.5) |

| Gender | |

| Female, n/N (%) | 87/166 (52.4%) |

| Male, n/N (%) | 76/166 (45.8%) |

| Unknown, n/N (%) | 3/166 (1.8%) |

| Working environment | |

| University or university hospital | 104/166 (62.7%) |

| University of applied sciences | 18/166 (10.8%) |

| Academic institution (non-university) | 15/166 (9.0%) |

| Non-university hospital | 12/166 (7.2%) |

| Private company | 12/166 (7.2%) |

| Private practice | 2/166 (1.2%) |

| Other | 3/166 (1.8%) |

| Role of the researcher | |

| Principal investigator or investigator | 80/166 (48.2%) |

| Project leader or project manager | 26/166 (15.7%) |

| Research assistant or research collaborator | 20/166 (12.1%) |

| Sponsor | 15/166 (9.0%) |

| Sponsor-investigator | 13/166 (7.8%) |

| Employee of a contract research organisation | 2/166 (1.2%) |

| Other | 9/166 (5.4%) |

| Missing | 1/166 (0.6%) |

| Professional function | |

| Non-medical researcher | 59 (35.5%) |

| Medical researcher | 43 (25.9%) |

| Clinician | 23 (13.9%) |

| Project manager or monitor | 18 (10.8%) |

| Nurse in patient care | 4 (2.4%) |

| Research nurse | 2 (1.2%) |

| Other | 16 (9.6%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Experience in research (years), mean (range) | 9.9 (8.5–11.3). |

The majority of respondents (94/166; 56.6%) reported that all the questions they were asked during the submission of the jurisdictional inquiry were easy to understand (table 5). However, some respondents (39/166; 23.5) reported that one or several were difficult to understand. Questions identified as difficult included “Will this project generate generalisable knowledge?” (n = 15), “Is it solely a quality control for institution-internal purposes?” (n = 15), “Are samples or health-related data involved?” (n = 14), “Are the samples/ data irreversibly anonymised?” (n = 13), “Are persons involved?” (n = 7).

Table 5 Reported difficulties during submission process.

| Difficulties | Total |

|---|---|

| Comprehension of questions | |

| All questions were easy to understand | 94/166 (56.6%) |

| One or several questions were difficult to understand | 39/166 (23.5%) |

| I do not remember | 20/166 (12.1%) |

| I did not fill in this form | 10/166 (6%) |

| I had other difficulties with this form | 2/166 (1.2%) |

| Missing | 1/166 (0.6%) |

| Types of difficult questions (multiple answers were possible) | |

| “Will this project generate generalisable knowledge” | 15/69 (21.7%) |

| “Is it solely a quality control for institution-internal purposes” | 15/69 (21.7%) |

| “Are samples or health-related data involved” | 14/69 (20.3%) |

| “Are the samples/ data irreversibly anonymised?” | 13/69 (18.8%) |

| “Are persons involved?” | 7/69 (10.1%) |

Respondents reported that virtually all of the projects (111/112; 99%) that were assessed by research ethics committees as not needing ethical approval were started or planned to start (table 6). Out of those projects which were determined to need ethical approval, 80% (36/45) were started or planned to start. Consequently, 88% (147/166) of all projects were started or planned to start. The vast majority (154/166; 93%) of respondents agreed with the decisions made by research ethics committees.

Table 6 Reported outcome of project.

| Outcome | Need for ethical approval | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Needed ethical approval | Did not need ethical approval |

Total

(N = 166) |

|

| Started or is planned to start | 36/45 (80%) | 111/112 (99.1) | 147/166 (88.5) |

| Not started | 9/45 (20%) | 1/112 (0.9) | 10 (6) |

| Other | 7 (4.2%) | ||

| Missing | 2 (1.2%) | ||

This is the first study to examine the underlying reasons for jurisdictional inquiries concerning the Human Research Act in Switzerland and it has resulted in two key findings: (1) Jurisdictional inquiries were often prompted by uncertainty about whether the project should be considered “research” or involved fully anonymised data under the Human Research Act, and (2) the majority of jurisdictional inquiries included persons as subjects but were determined not to require ethical approval. These findings often reflect persistent structural issues that many other countries also face.

Ethical oversight systems around the world typically make a sharp distinction between clinical research and clinical practice. As a result, researchers wanting to conduct research studies involving humans are typically required to obtain prior approval from an independent ethics committee, to fully inform participants about the study and obtain their written consent agreeing to participate [4]. However, many projects in the healthcare setting are increasingly not clearly fitting the “research” or “practice” distinction, which can lead to uncertainty about how some projects should be ethically handled. For instance, qualitative research studies in the US involving health care leaders [5], and those responsible for quality improvement [8], have highlighted persistent difficulties in determining which healthcare improvement projects need to be submitted to a research ethics committee and disclosed to patients.

Our findings regarding the underlying reasons for the jurisdictional inquiries are also supported by a recently published qualitative study with key stakeholders in Switzerland by McLennan [3]. Similar to our analysis of jurisdictional inquiries, it was reported that there is widespread uncertainty among key stakeholders regarding when certain activities require ethical review because of two main factors: (1) many projects fall into a “grey zone” where “research” cannot always be clearly differentiated from “non-research”; and (2) there is confusion about when health data should be considered fully anonymised [3].

Difficulties in correctly interpreting these terms in the Human Research Act may be partly caused by a lack of clarity in the legislation itself. Indeed, swissethics has recommended that the terms “research” and “anonymous data” should be better defined in the Human Research Act [18]. However, it is also clear that Swiss researchers need to be provided with more support and guidance in determining whether their projects require ethical approval. It has been recently reported that the vast majority of Swiss healthcare institutions currently do not have clear and systematic internal policies and procedures in place to determine which projects require ethical approval [3]. This is concerning and is likely causing some researchers to instead contact research ethics committee for guidance via a jurisdictional inquiry. Having clear internal policies and procedures to determine the need for ethical approval has been identified as important [5, 7] and Swiss healthcare institutions should work towards developing such guidance. Assessment tools developed in other countries may provide helpful models [19, 20].

However, it should be noted that 46 jurisdictional inquiries requesting clarification whether the project had to be submitted for ethical approval did not reveal any uncertainties regarding the correct interpretation of the Human Research Act and 50 requested a declaration of no objection. It is therefore possible that there were other factors influencing a number of researchers’ decisions to submit a jurisdictional inquiry, other than being uncertain about the correct interpretation of the Human Research Act. The study by McLennan also revealed that many Swiss researchers are submitting to research ethics committees projects that they know do not fall under the Human Research Act [3]. Due to a general lack of oversight mechanisms for projects falling outside of the Human Research Act, researchers are requesting a confirmation from research ethics committees that their project does not require ethics approval because they are intending to publish the results or to meet requirements set by funders [3]. However, “[t]his was seen by many as ethically problematic, not only because it creates inefficiencies and wastes resources for the ethics committees, but also because it can give the impression that a project has been ethically reviewed when it has not been” [3].

Although there is a growing number of institutions in Switzerland (the Ethics Commission of ETH Zurich, the University of Zurich, the University of Basel, and many Faculties of Psychology, etc.) that provide ethical oversight for projects outside of the Human Research Act, there are often limited ethical oversight mechanisms available for these projects. Consequently, a number of research projects involving humans in Switzerland do not receive ethical approval, because they do not constitute “research” for the purposes of the Human Research Act. Indeed, we found in our mixed-methods study that the majority of jurisdictional inquiries included persons as subjects but were determined not to require ethical approval. However, it should be noted that article 51(2) of the Human Research Act states that ethics committees “…may advise researchers in particular on ethical questions and, if so requested by the researchers, comment on research projects not subject to this Act and specifically projects carried out abroad”. Ethics committees will therefore often state in response to jurisdictional inquiries that they have “reviewed the submitted documents and can confirm that the research project fulfils the general ethical and scientific standards for research with humans”. This is not, however, a full ethical review of the project. Swissethics has also recommended that declarations of no objections are no longer issued by research ethics committees as in the past [18]. It will therefore be important that more consideration is given to how the ethical oversight of projects falling outside human research legislation can be strengthened.

This mixed-methods study has a number of limitations that should be taken into account when interpreting the results. Due to time constraints of the project, data was only collected over 6 months in the second half of 2017. Although analysis of the national sample reached saturation in the difficulties researchers had with correctly interpreting the Human Research Act, it is possible that some difficulties were not sufficiently represented in the study because of the short data collection timeframe. Furthermore, the qualitative analysis of the jurisdictional inquiries involved a level of interpretation, introducing a subjective element to the analysis. Nevertheless, as multiple authors were involved in the analysis and met regularly to discuss challenges with interpretations, this process should ensure as much as possible the reliability and validity of the findings. As the survey of submitting researchers had a response rate of less than 60% (166/292; 56.8%), a generalisation of the results to submitting researchers is not necessarily possible. However, as those who responded to our survey are likely to be generally more motivated and more interested than the non-respondents, the difficulties identified should be taken seriously. Furthermore, because the two data sources (BASEC and survey) were not linked with respect to specific projects, a more detailed comparison between the two data sources was not possible. Finally, because the survey was initiated before the completion of the qualitative analysis in which we found out that 25 of the submitted files were actually not jurisdictional inquiries, all 296 submitting researchers were surveyed, and due to the anonymous survey analysis we could not exclude any respondents based on our findings in the qualitative analysis.

Jurisdictional inquiries are an important means for researchers to clarify whether their project requires ethical oversight. However, our mixed-methods study revealed that a number of researchers are having difficulties correctly interpreting some legal terms in the Human Research Act. Better defining these terms in the Human Research Act may be helpful, but Swiss researchers also need to be provided more support and guidance in determining whether or not their projects require ethical approval. Strengthening the ethical oversight of projects falling outside human research legislation may further improve this process.

The appendix is available as a separate file at https://smw.ch/article/doi/smw.2020.20318.

We thank Michael Tüller (informatics, swissethics) for providing us with access to the BASEC data. We are grateful to Andrea Raps (Swiss Federal Office of Public Health, Division of Biomedicine, Human Research Section, Bern) for her helpful comments when writing the report. We thank Federico Cathieni (Center for Primary Care and Public Health - Unisanté, Lausanne) for his help with the survey implementation. Finally, we very much thank all researchers who participated in the survey.

This study was initiated and funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health in collaboration with swissethics. MR, BL, and BM are employed by the Federal Office of Public Health. The Federal Office of Public Health is responsible for the Human Research Act and the evaluation, which aims at assessing the effectiveness of the Human Research Act and its ordinances. SD, PG, and BH are representatives of swissethics or the research ethics committee in Geneva. MR, BL, BM, SD, PG, and BH were involved in the concept and design, data analysis, revising the manuscript, and final approval; they were not involved in data collection. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

1 Kass NE , Faden RR , Goodman SN , Pronovost P , Tunis S , Beauchamp TL . The research-treatment distinction: a problematic approach for determining which activities should have ethical oversight. Hastings Cent Rep. 2013;43(s1):S4–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.133

2Shelley-Egan C, Brey P, Rodrigues R, Douglas D, Gurzawska A, Bitsch L, et al. Ethical Assessment of Research and Innovation: A Comparative Analysis of Practices and Institutions in the EU and selected other countries. 2016. Available from: https://satoriproject.eu/media/D1.1_Ethical-assessment-of-RI_a-comparative-analysis-1.pdf

3 McLennan S . The ethical oversight of learning health care activities in Switzerland: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31(8):G81–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzz045

4 McLennan S , Kahrass H , Wieschowski S , Strech D , Langhof H . The spectrum of ethical issues in a Learning Health Care System: a systematic qualitative review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(3):161–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzy005

5 Morain SR , Kass NE . Ethics Issues Arising in the Transition to Learning Health Care Systems: Results from Interviews with Leaders from 25 Health Systems. EGEMS (Wash DC). 2016;4(2):3. doi:.https://doi.org/10.13063/2327-9214.1212

6 Fiscella K , Tobin JN , Carroll JK , He H , Ogedegbe G . Ethical oversight in quality improvement and quality improvement research: new approaches to promote a learning health care system. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(1):63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0056-2

7 Finkelstein JA , Brickman AL , Capron A , Ford DE , Gombosev A , Greene SM , et al. Oversight on the borderline: Quality improvement and pragmatic research. Clin Trials. 2015;12(5):457–66. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1740774515597682

8 Whicher D , Kass N , Saghai Y , Faden R , Tunis S , Pronovost P . The views of quality improvement professionals and comparative effectiveness researchers on ethics, IRBs, and oversight. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2015;10(2):132–44. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1556264615571558

9 Thompson DA , Kass N , Holzmueller C , Marsteller JA , Martinez EA , Gurses AP , et al. Variation in local institutional review board evaluations of a multicenter patient safety study. J Healthc Qual. 2012;34(4):33–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1945-1474.2011.00150.x

10 Miller FG , Emanuel EJ . Quality-improvement research and informed consent. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(8):765–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp0800136

11 Siegel MD , Alfano SL . The ethics of quality improvement research. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(2):791–2. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318194c4d6

12 Taylor HA , Pronovost PJ , Faden RR , Kass NE , Sugarman J . The ethical review of health care quality improvement initiatives: findings from the field. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2010;95:1–12.

13 Kass N , Pronovost PJ , Sugarman J , Goeschel CA , Lubomski LH , Faden R . Controversy and quality improvement: lingering questions about ethics, oversight, and patient safety research. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2008;34(6):349–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(08)34044-6

14 https://www.swissethics.ch/.

15Federal Office of Public Health. Evaluation of the Human Research Act. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/medizin-und-forschung/forschung-am-menschen/evaluation-humanforschungsgesetz.html Accessed 2020 January 10.

16Schreier M. Qualitative content analysis in practice. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2012.

17 Hsieh HF , Shannon SE . Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–88. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

18Schweizerische Ethikkommissionen für die Forschung am Menschen. Ergebnisse der Arbeitsgruppe von swissethics zur Revision des Humanforschungsgesetz es (HFG) und der Verordnungen. 2018; https://swissethics.ch/doc/gesetzrichtl/Bericht_Arbeitsgruppe_HFG_final_Web.pdf Accessed 2020 January 10

19Alberta Innovates. ARECCI Ethics Guideline Tool. 2017; https://albertainnovates.ca/our-health-innovation-focus/a-project-ethics-community-consensus-initiative/arecci-ethics-guideline-and-screening-tools/ Archived at: http://www.webcitation.org/76hnxgqPG. Accessed 2020 January 10

20Medical Research Council Regulatory Support Centre - Health Research Authority. Is my study research? http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/research/question3.html Accessed 2020 January 10

This study was initiated and funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health in collaboration with swissethics. MR, BL, and BM are employed by the Federal Office of Public Health. The Federal Office of Public Health is responsible for the Human Research Act and the evaluation, which aims at assessing the effectiveness of the Human Research Act and its ordinances. SD, PG, and BH are representatives of swissethics or the research ethics committee in Geneva. MR, BL, BM, SD, PG, and BH were involved in the concept and design, data analysis, revising the manuscript, and final approval; they were not involved in data collection. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.