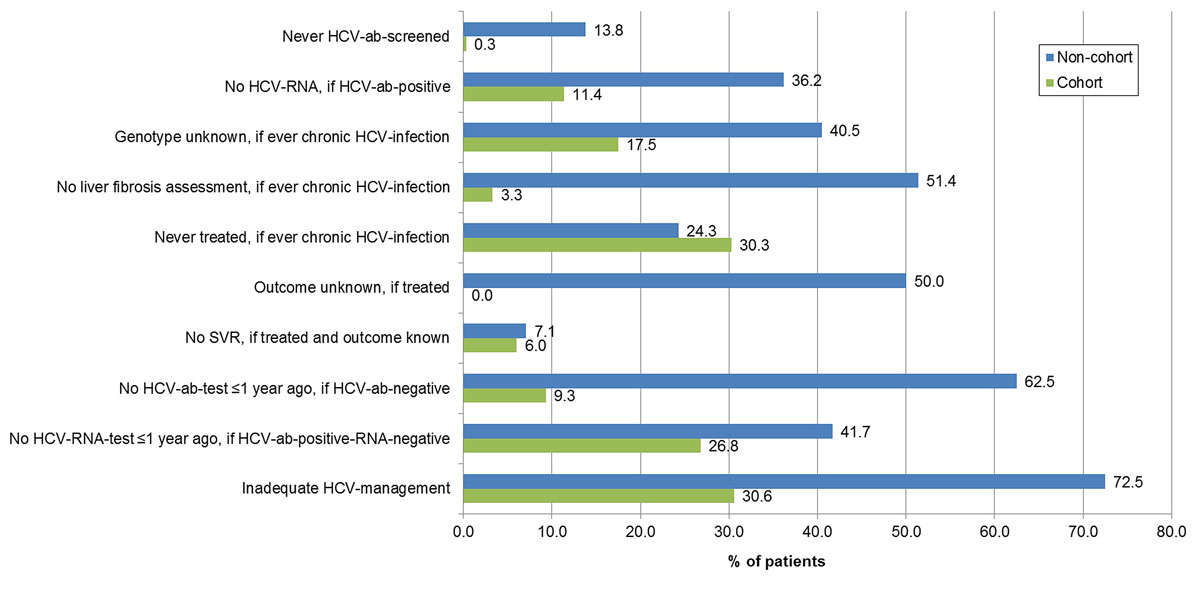

Figure 1 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) cascade of non-cohort and cohort patients.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20317

Hepatitis C is a blood-borne viral infection. Most cases of acute hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection (approximately 80%) are anicteric and asymptomatic [1]. Whereas 25% of the infected persons spontaneously clear the virus within 6 months [2], 75% develop chronic disease and need treatment. Many patients with chronic hepatitis C are symptomatic, but symptoms are not specific and appear slowly over time, and thus are often not recognised as HCV related by patients (and doctors) [3]. About 20% of the chronically infected develop liver cirrhosis after 20 years [4], with an annual risk of hepatocellular carcinoma of 1–5% and of hepatic decompensation of 3–6%. Thus, hepatitis C may become a “silent killer” [5]. With approximately 71 million chronically HCV infected people worldwide, it is a global health problem [1].

HCV transmission occurs via blood, e.g., by sharing equipment for injection (needle, syringe, water, spoon, filter) or intranasal drug use (snorting straws) [6], unscreened transfusions or, less commonly, sexual practices leading to blood exposure [1].

Globally, there are 15.9 million people who inject drugs, with 52.3% (42.4–62.1%), equating to 8.2 million, estimated to be HCV antibody positive and 9.1% (5.1–13.2%), equating to 1.4 million, hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen positive [7].

HCV seroprevalence in Switzerland is 0.7% in the general population [8], 26–48% in those on oral opioid agonist therapy (OAT) (other than heroin) and 60–80% in heroin substitution programmes [9]. It is estimated that 36,000–43,000 persons are chronically HCV infected in Switzerland. Five times more people die due to HCV infection than due to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or HBV infection [8]. Intravenous drug use accounts for the majority of HCV infections in Switzerland [10], with 7700–15,400 HCV-infected drug users [9]. Of the 22,000–27,000 people who use drugs in Switzerland, about 80% are cared for in OAT programmes (oral OAT [other than heroin]: 18,000; heroin: 1600). In 60%, OAT is prescribed by the general practitioner (GP) [11]. About 27% of the OAT patients have ongoing intravenous drug use [12].

In the era of pangenotypic interferon-free direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatment (since 2016/2017), chronic hepatitis C can be cured within 8–12 weeks [13]. Better tolerability and shorter treatment duration compared with interferon-based treatments have led to fewer preterm stops and adherence problems [14, 15]. The sustained virological response (SVR) rate has increased to >95%, irrespective of genotype, HIV co-infection, cirrhosis and prior unsuccessful interferon-based treatment [15, 16]. Equal treatment efficacy has been shown for OAT patients with ongoing injection or non-injection drug use [17–20].

Until 2017, DAA reimbursement in Switzerland was restricted to patients with at least a significant degree of liver fibrosis (≥F2) [21]. Since then these restrictions have been removed [22]. However, because of the high costs, only infectious disease specialists or gastroenterologists and addiction specialists with experience in HCV treatment are allowed to prescribe DAAs, whereas all physicians in Switzerland could prescribe interferon and ribavirin.

Both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Swiss Hepatitis Strategy aim at HCV elimination by the year 2030 [23, 24]. In March 2019, the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) published official guidelines for HCV management in drug users [25]. Key points already mentioned in earlier national [26] and international recommendations [27] are:

The canton Aargau is a mixed urban and rural area in Northwestern Switzerland with about 670,000 inhabitants. Between 2013 and 2015, about one third of the 631 patients living and receiving OAT in the canton Aargau were enrolled into the cohort study “Management of hepatitis C in drug substitution programmes – canton Aargau”, offering HCV/HIV antibody rapid testing, noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment with mobile Fibroscan® and, since August 2017, capillary HCV RNA rapid testing with the GeneXpert® to improve HCV screening and treatment uptake [28, 29]. By the end of August 2018, the number of study participants had increased to 330. However, for 592 OAT patients in the canton Aargau, HCV management was still unknown. It was hypothesised that it was worse than for patients within the Argovian OAT cohort study.

The aim of the study was to describe the current HCV management in OAT patients of the Swiss canton Aargau in view of the FOPH guidelines and to compare the management within and outside the cohort study.

The study “Management of hepatitis C in drug substitution programmes – canton Aargau” (Argovian OAT cohort study) was approved by the cantonal ethics committee (AG/SO 2012/091). All participants gave written informed consent before any disclosure of personal data. Almost all participants were also enrolled into the Swiss Association for the Medical Management in Substance Users (SAMMSU) cohort, which was approved by the leading ethics committee St Gallen (EKSG 13/144).

In Switzerland, hepatitis C is a notifiable disease, of which the cantonal physician must be informed. In addition, the cantonal physician has to approve OAT treatments at regular intervals, i.e., every one or two years. The analysis of cantonal data collected by a questionnaire which was sent by the cantonal physician to the OAT prescriber of OAT patients not yet enrolled into the above mentioned Argovian OAT cohort study until the end of August 2018 was rated by the ethics committee of the University of Basel (EKNZ) as a quality assurance project not needing formal ethical approval.

According to the national substitution statistics of Switzerland [30], the number of OAT patients in the canton Aargau ranged from a minimum of 680 patients in 2014 to a maximum of 870 patients in 2017, with an average of 765 patients for the years 2012–2019. However, this number includes patients living in the canton Aargau but receiving their OAT in a different canton (about 170 in 2013 [28]), who are not eligible for the Argovian OAT cohort study, and excludes patients exclusively receiving heroin, who are centrally managed by the FOPH.

Between July 2013 and August 2018, 330 patients were enrolled into the Argovian OAT cohort study, which is described in more detail in a former publication [28]. All patients living and receiving OAT in the canton Aargau are eligible. At study entry and yearly follow-up, free HIV/HCV antibody rapid testing, noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment (Fibroscan®) and since August 2017 capillary HCV RNA rapid testing with the GeneXpert® [29] are offered to improve HCV screening and treatment uptake. Whenever possible, follow-up continues if patients discontinue OAT or leave the canton. To assess HCV management, all information available before 01 September 2018 was considered.

In September 2018, 592 of the then 809 OAT patients were not yet enrolled into the cohort study. For them, the cantonal physician sent a questionnaire regarding HCV, HIV, HAV and HBV to the OAT prescriber, which also included an option to refer patients for further evaluation (appendix 1). Up to August 2019, we had received 182 (31%) questionnaires, of which 160 were eligible for analysis (22 patients no longer receiving OAT in the canton Aargau excluded). Twenty-eight (61%) of 46 patients referred for further assessment kept the appointment.

HCV positivity/infection means HCV antibody positivity.

Chronic HCV infection was defined as detectable HCV RNA at least 6 months after infection or diagnosis and/or if the patient ever received HCV treatment.

Sustained virological response (SVR) means undetectable HCV RNA at least 12 weeks after completed therapy.

Adequate HCV management was defined as an HCV antibody test ≤1 year ago if HCV antibody negative or last HCV RNA test negative, and ≤1 year ago if HCV antibody positive.

Inversely, inadequate HCV management was defined as one of the following:

Categorical variables were compared using the chi-square test. Continuous variables were analysed with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS version 24.

For calculating the time since the last HCV antibody/RNA test, the reference date was the last follow-up date for cohort patients and the date the questionnaire was filled in for non-cohort patients.

Of the 592 questionnaires sent by the cantonal physician to the OAT prescribers of patients not yet enrolled into the Argovian OAT cohort by the end of August 2018, 182 were returned as of September 2019, corresponding to a response rate of 30.7%. After exclusion of 22 patients who no longer received OAT in the canton Aargau, 160 non-cohort patients remained for the analysis.

Of the 330 patients enrolled into the Argovian OAT cohort study between July 2013 and August 2018, 205 were recruited between July 2013 and July 2015. Of these, 104 (50.7%) were recruited in a decentralised setting (family practice / pharmacy) and 101 (49.3%) in a centralised setting (heroin programme, addiction clinic, infectious diseases outpatient clinic) [28]. An additional 125 patients were enrolled between August 2015 and August 2018, mainly in a centralised setting. For all cohort patients, the median time since registration was 3.4 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.1–4.6, range 0.1–5.2) and the median time since the last follow-up 2.2 years (IQR 1.3–3.8, range 0.1–5.2). The last follow-up before 1 September 2018 was in 70.6% (233) the registration visit, in 23.0% (76) the first, in 6.1% (20) the second and in 0.3% (1) the third follow-up.

The 160 non-cohort patients were mainly cared for in a decentralised setting (family practice / pharmacy).

Both non-cohort and cohort patients were predominantly male (71% and 77%, respectively) (table 1). Non-cohort patients were significantly older (median age 48 vs 42 years), had a significantly lower proportion who had ever used intravenous drugs (65% vs 75%) and had their first intravenous drug use in earlier decades. At 19 and 20 years, respectively, the median age at first intravenous drug use was comparable. HCV and HIV antibody prevalences were slightly lower in non-cohort patients (42% vs 47%, p = 0.344 and 2% versus 6% (p = 0.082), respectively). The proportion of HCV positive patients with ever IDU was 96.5% (56/58) in non-cohort patients and 95.5% (147/154) in cohort-patients at registration.

Table 1 Patient characteristics.

|

Non-cohort patients

(n = 160) |

Cohort patients

(n = 330) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 71.3% (114) | 77.3% (222) | 0.147 |

| White ethnicity | 100% (328/328) | ||

| Median age (y) (IQR) | 48 (42–53) | 42 (34–49)* | <0.001 |

| Median BMI (kg/m2) (IQR) | 24.2 (21.6–27.6)* (n = 305) | ||

| Ever used intravenous drugs | 64.5% (100/155) | 74.8% (246/329)† | 0.020 |

| IDU start year, if known | |||

| 1970–1979 | 2.6% (2/78) | 3.8% (9/234) | 0.595 |

| 1980–1989 | 43.6% (34/78) | 20.9% (49/234) | <0.001 |

| 1990–1999 | 37.2% (29/78) | 25.6% (60/234) | 0.051 |

| 2000–2009 | 12.8% (10/78) | 29.5% (69/234) | 0.003 |

| 2010–2019 | 3.8% (3/78) | 20.1% (47/234) | <0.001 |

| Median age at first IDU (y) (IQR) | 19 (17–23) (n = 79) |

20 (17–25) (n = 234) |

0.077 |

| Ever used intranasal drugs | 88.7% (291/328)# | ||

| Ever consumed: | |||

| Heroin | 98.8% (326)† | ||

| Cocaine | 92.1% (302/328)† | ||

| Benzodiazepines | 68.2% (221/324)† | ||

| Cannabis | 88.3% (288/326)† | ||

| Daily alcohol consumption (g/d) | (n = 212) | ||

| 0 | 68.4% (145)* | ||

| 1–24 | 15.1% (32)* | ||

| 25–48 | 5.2% (11)* | ||

| 49–96 | 5.2% (11)* | ||

| >96 | 6.1% (13)* | ||

| Ongoing IDU, if ever | 23.7% (28/118)* | ||

| Ongoing intranasal drug use, if ever | 32.0% (39/122)* | ||

| Ongoing heroin use‡ | 30.6% (41/134)* | ||

| Ongoing cocaine use‡ | 26.7% (32/120)* | ||

| Ongoing benzodiazepine use‡ | 20.0% (18/90)* | ||

| Ongoing cannabis use‡ | 25.7% (27/105)* | ||

| Substitution treatment | 93.9% (310)* | ||

| Median time in the programme (y) (IQR) | 1.4 (0.3–5.9)†

(n = 309) |

||

| Attendance | (n = 289) | ||

| Daily (5–7×/week) | 62.6% (181)* | ||

| 2–4×/week | 14.5% (42)* | ||

| ≤1×/week | 22.8% (66)* | ||

| Opioid agonist therapy§ | |||

| Heroin | 9.7% (32)* | ||

| Methadone | 52.7% (174)* | ||

| Levomethadone | 1.2% (4)* | ||

| Buprenorphine | 18.8% (62)* | ||

| Retarded morphine | 20.6% (68)* | ||

| Diazepam | 6.7% (22)* | ||

| Ritalin | 1.5% (5)* | ||

| Ever attempted suicide | 26.2% (85/324)† | ||

| HCV antibody positive | 42.0% (58/138) | 46.8% (154/329)† | 0.344 |

| HIV antibody positive | 2.2% (3/135) | 6.1% (20/329)† | 0.082 |

BMI = body mass index; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; IDU = intravenous drug use; IQR = interquartile range * At the last follow-up before 01/09/2018; † at registration; ‡ if ever; § more than one answer allowed

For cohort patients, further characteristics concerning drug and alcohol consumption as well as OAT are available in table 1.

The HCV serostatus was known for all but one of the 330 cohort patients (99.7%), compared with only 138 (86.3%) of the 160 non-cohort patients (p <0.001) (table 2, fig. 1). A total of 167 (50.8%) of the cohort and 58 (42.0%) of the non-cohort patients were HCV antibody positive (p = 0.085). The proportions with known HCV RNA were 88.6% (148) and 63.8% (37), respectively, (p <0.001).

Table 2 HCV management.

|

Non-cohort patients

(n = 160) (Sept. 2018 to Sept. 2019) |

Cohort patients

(n = 330) (last FUP before 01 Sept. 2018) |

p-value | Difference (%) Cohort − non-cohort (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCV cascade | ||||

| HCV serostatus known | 86.3% (138) | 99.7% (329/330) | <0.001 | 13.4 (8.1–18.8) |

| HCV antibody positive | 42.0% (58/138) | 50.8% (167/329) | 0.085 | 8.7 (–1.1–18.6) |

| HCV RNA known, if HCV antibody positive | 63.8% (37/58) | 88.6% (148/167) | <0.001 | 24.8 (11.6–38.1) |

| – Currently HCV RNA positive | 35.1% (13/37) | 24.3% (36/148) | 0.183 | –10.8 (–27.7–6.1) |

| Ever chronic HCV infection | 80.4% (37/46) | 81.1% (120/148) | 0.922 | 0.6 (–12.4–13.7) |

| If ever had chronic HCV infection: | (n = 37) | (n = 120) | ||

| – Genotype known | 59.5% (22) | 82.5% (99) | 0.004 | 23.0 (5.8–40.3) |

| – Liver biopsy | 24.3% (9) | 38.3% (46) | 0.118 | 14.0 (–2.3–30.3) |

| – Fibroscan® | 35.1% (13) | 95.0% (114) | <0.001 | 59.9 (44.0–75.7) |

| – Liver fibrosis assessment (liver biopsy or Fibroscan®) | 48.6% (18) | 96.7% (116) | <0.001 | 48.0 (31.6–64.4) |

| – Ever treated | 75.7% (28/37) | 70.0% (84) | 0.505 | –5.7 (–21.7–10.4) |

| – Outcome known | 50.0% (14/28) | 100.0% (84/84) | <0.001 | 50.0 (31.5–68.5) |

| – SVR, if outcome known | 92.9% (13/14) | 94.0% (79/84) | 0.863 | 1.2 (–13.2–15.6) |

| Yearly HCV screening | ||||

| Last HCV antibody test ≤1 year ago, if HCV-antibody-negative | 37.5% (30/80) | 90.7% (147/162) | <0.001 | 53.2 (41.7–64.8) |

| Last HCV RNA test ≤1 year ago, if HCV antibody positive / RNA negative | 58.3% (14/24) | 73.2% (82/112) | 0.147 | 14.9 (–6.5–36.2) |

| Adequate HCV management* | 27.5% (44/160) | 69.4% (229/330) | <0.001 | 41.9 (33.4–50.4) |

| HIV | ||||

| HIV serostatus known | 84.4% (135/160) | 99.7% (329/330) | <0.001 | 15.3 (9.7–21.0) |

| Last HIV antibody test ≤1 year ago, if HIV antibody negative | 34.8% (46/132) | 85.1% (263/309) | <0.001 | 50.3 (41.2–59.3) |

| HIV antibody positive | 2.2% (3/135) | 6.1% (20/329) | 0.082 | 3.9 (0.3–7.4) |

| HIV-HCV co-infected | 100% (3/3) | 100% (20/20) | 0 | |

| ART, if HIV positive | 100% (3/3) | 100% (20/20) | 0 | |

| HAV | ||||

| HAV serology available | 38.1% (61/160) | 37.9% (125/330) | 0.958 | –0.2 (–9.4–8.9) |

| Immunity against HAV, if HAV serology available | 42.6% (26/61) | 57.6% (72/125) | 0.055 | 15.0 (–1.6–30.1) |

| HBV | ||||

| HBV serology available | 45.0% (72/160) | 53.0% (175/330) | 0.096 | 8.0 (–1.4–17.4) |

| Interpretable HBV serology available | 24.4% (39/160) | 44.8% (148/330) | <0.001 | 20.5 (11.9–29.0) |

| If interpretable HBV serology available: | ||||

| – Immunity after vaccination† | 25.6% (10/39) | 25.7% (38/148) | 0.997 | 0.0 (–15.4–15.4) |

| – Immunity after infection‡ | 43.6% (17/39) | 35.1% (52/148) | 0.330 | –8.5 (–25.8–8.9) |

| – Immunity, unclear§ | 10.3% (4/39) | 6.1% (9/148) | 0.362 | –4.2 (–14.4–6.1) |

| – No immunity¶ | 17.9% (7/39) | 30.4% (45/148) | 0.122 | 12.5 (–1.7–26.6) |

| – chronic hepatitis B‖ | 2.6% (1/39) | 2.7% (4/148) | 0.962 | 0.1 (–5.5–5.7) |

ART = antiretroviral therapy; CI = confidence interval; FUP = follow-up; HAV = hepatitis A virus; HBV = hepatitis B virus; HCV = hepatitis C virus; HIV = human immunodeficiency virus; SVR = sustained virological response; * last HCV-antibody-test ≤1 year ago, if HCV-antibody-negative or last HCV-RNA-test ≤1 year ago, if HCV-antibody-positive-RNA-negative; † anti-HBs positive/>10 U/l and anti-HBc negative; ‡ anti-HBc positive and HBs-Ag negative; § anti-HBs positive and anti-HBc unknown; ¶ anti-HBs and anti-HBc negative; ‖ HBs-Ag positive

Figure 1 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) cascade of non-cohort and cohort patients.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

In cases who had ever had chronic HCV infection (120 cohort and 37 non-cohort patients), the proportion with a known HCV genotype was 82.5% (n = 99) and 59.5% (n = 22) (p = 0.004) and the proportion who had ever had a liver fibrosis assessment 96.7% (116) and 48.6% (18), respectively, (p <0.001). There was no difference in the proportion ever treated (70.0%, n = 84 vs 75.7%, n = 28) and in the proportion of treated patients achieving SVR, if the outcome was known (94.0%, 79/84 vs 92.9%, 13/14). However, for all cohort patients the treatment outcome was known, compared with only 50.0% (14) of the non-cohort patients. The proportion of interferon-free treatments among all treatments was comparable in cohort and non-cohort patients (49.0%, 49/100 vs 42.9%, 12/28; p = 0.565).

Among the 37 HCV antibody positive non-cohort patients with known HCV RNA, the HCV RNA prevalence was 35.1% (13), which is comparable to the HCV RNA prevalence among the 148 HCV antibody positive cohort patients with known HCV RNA, i.e., 24.3% (36) (p = 0.183). With all non-cohort patients and all cohort patients as the denominator, the HCV RNA prevalences were 8.1% (13/160) and 10.9% (36/330), respectively (p = 0.335).

Overall, 69.4% (229/330) of the cohort patients, but only 27.5% (44/160) of the non-cohort patients had adequate HCV management (p <0.001), defined as last HCV antibody test ≤1 year ago, if HCV antibody negative (90.7%, 147/162 vs 37.5%, 30/80; p <0.001) or last HCV RNA test ≤1 year ago, if HCV antibody positive and RNA negative (73.2%, 82/112 vs 58.3%, 14/24; p = 0.147) (table 2, fig. 2). HCV-positive cohort patients were diagnosed between 1980 and 2017 and HCV-positive non-cohort patients between 1980 and 2019.

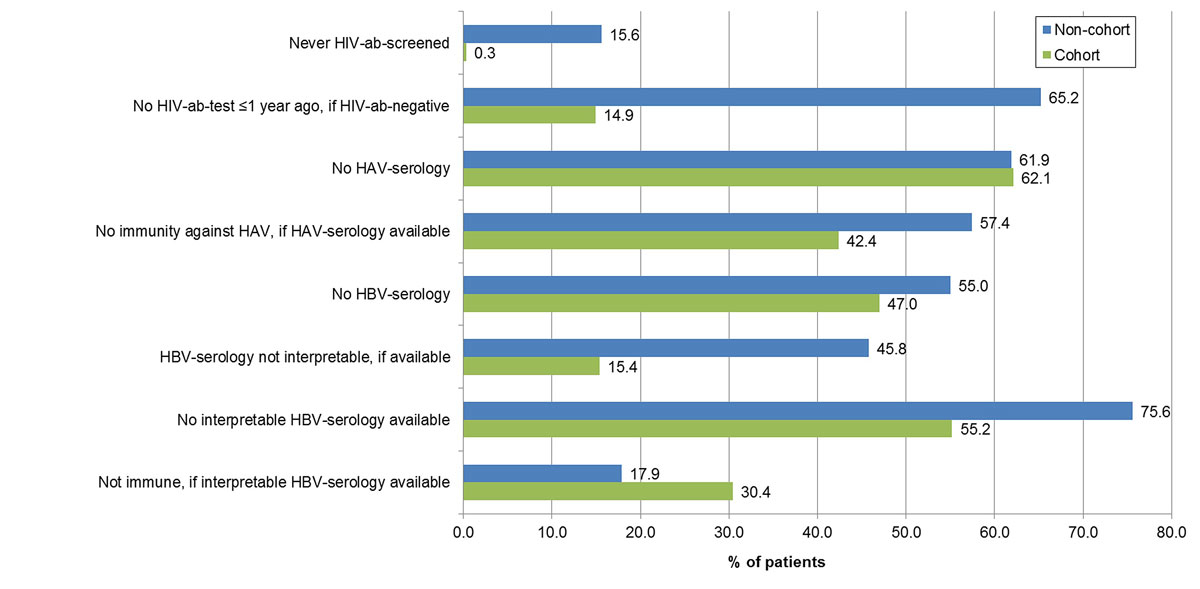

Figure 2 Gaps in the hepatitis C (HCV) management of non-cohort and cohort-patients.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

The proportion with unknown HIV serostatus was higher in non-cohort than the cohort patients (15.6%, 25/160 vs 0.3%, 1/330; p <0.001) (table 2, fig. 3). The HIV seroprevalence was slightly lower in non-cohort patients, at 2.2% (3/135) versus 6.1% (20/329) (p = 0.082). All HIV positive patients were HCV co-infected and under antiretroviral therapy. Overall, 85.1% (263/309) of the HIV negative cohort patients, but only 34.8% (46/132) of the HIV-negative non-cohort patients, had an HIV antibody test not older than one year (p <0.001). HIV-positive cohort patients were diagnosed between 1985 and 2008 and HIV-positive non-cohort patients between 1994 and 2005.

Figure 3 Gaps in the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis A and B viruses (HAV/HBV) management of non-cohort and cohort patients.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

In 62% of both the cohort and non-cohort patients, no HAV serology was available (table 2, fig. 3); 57.6% (72/125) of the cohort patients and 42.6% (26/61) of the non-cohort patients with an available HAV serology were immune to HAV (p = 0.055).

In 47.0% (155/330) of the cohort and 55.0% (88/160) of the non-cohort patients, no HBV serology was available (p = 0.096) (table 2, fig. 3). If HBV serology was available, it was interpretable in 84.6% (148/175) of the cohort, but only in 54.2% (39/72) of the non-cohort patients (p <0.001). Thus, in 44.8% of the cohort, but only in 24.4% of the non-cohort patients, interpretable HBV serology was available. Of these, 30.4% (45) and 17.9% (7), respectively, were not immune to HBV (p = 0.122), and 2.7% (4) and 2.6% (1) had chronic hepatitis B. In both cohort and non-cohort patients, immunity after infection was more frequent than immunity after vaccination.

Of the non-cohort patients, 46 were referred for further evaluation by either a gastroenterologist or an infectious disease specialist in the canton Aargau. Of these, 61% (28) kept the appointment, 17% (8) did not show up and 22% (10) still have an appointment. Overall, 6.3% (10/160) of all non-cohort patients rejected further evaluation and blood sampling.

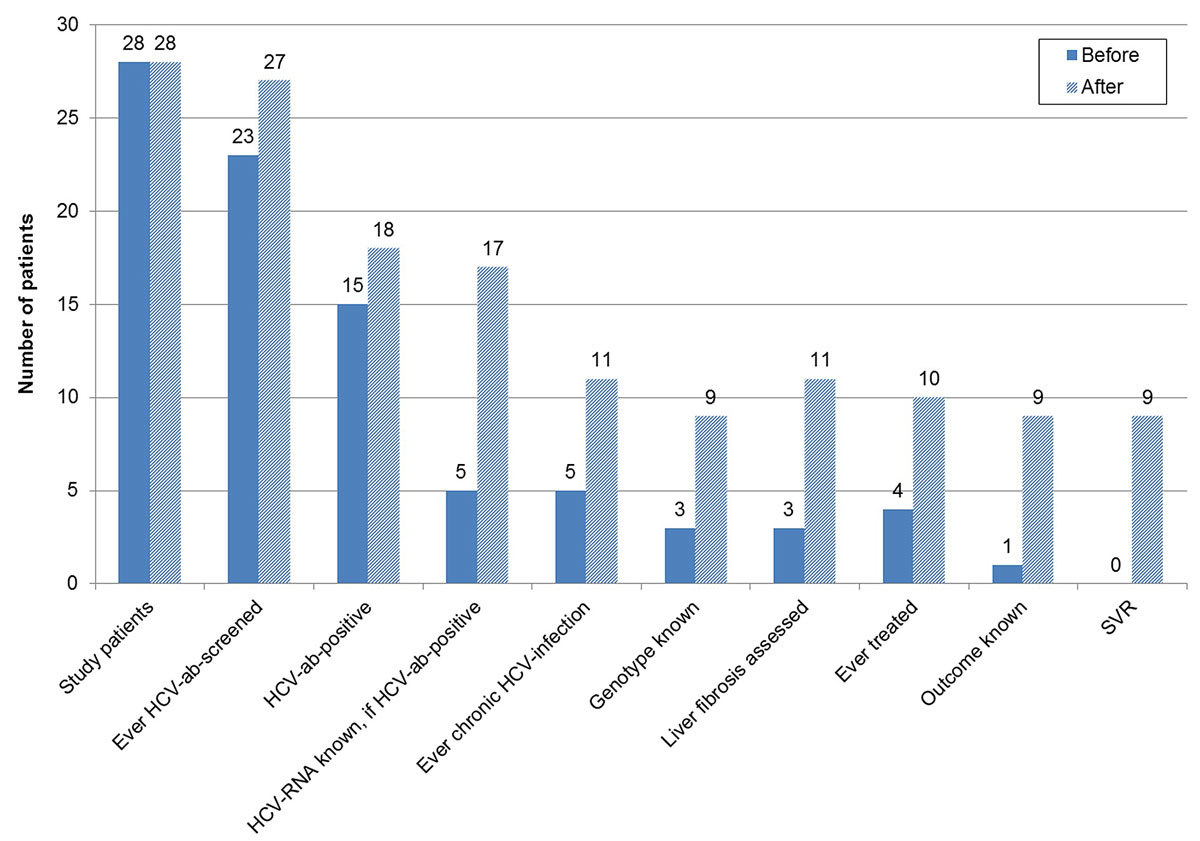

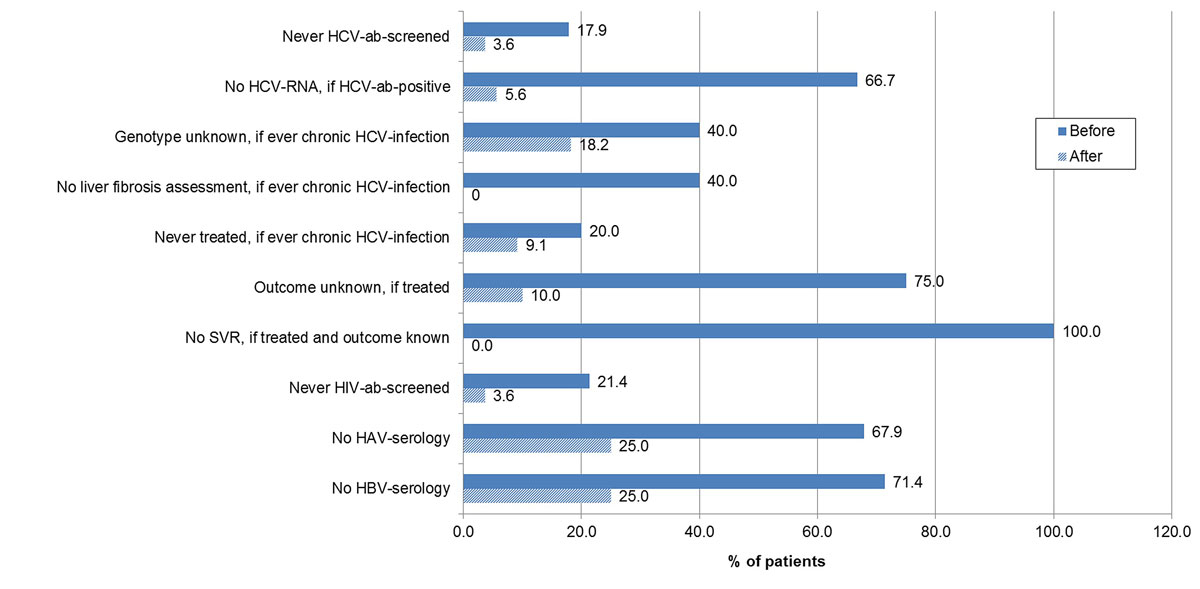

Of the 28 patients who were further evaluated, 75.0% (21) were male and 87.5% (21/24) had ever used intravenous drugs. The median age was 50.0 years (IQR 43.3–52.8). After evaluation by a gastroenterologist or infectious disease specialist, the proportion with unknown HCV serostatus decreased from 17.9% (5) to 3.6% (1) (p = 0.084) and the proportion of HCV antibody positives with unknown HCV RNA status from 66.7% (10/15) to 5.6% (1/18) (p <0.001) (figs 4 and 5 ). Two patients were newly diagnosed as HCV antibody positive and six patients were newly recognised as chronically HCV infected. Among the patients with ever chronic HCV infection, the proportion with unknown HCV genotype decreased from 40.0% (2/5) to 18.2% (2/11) (p = 0.350) and the proportion without a liver fibrosis assessment from 40.0% (2/5) to 0% (0/11) (p = 0.025). HCV treatment uptake increased from 80.0% (4/5) to 90.9% (10/11) (p = 0.541). Of the six additional patients treated, five were newly identified chronically infected patients and one had a known chronic HCV infection, which had not been treated in the past. All six patients were treated with DAAs. The proportion with unknown treatment outcome declined from 75% (3/4) to 10% (1/10) (p = 0.015). All nine treatments with known outcome were successful.

Figure 4 Hepatitis C virus (HCV) cascade of referred patients – before and after further evaluation.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

Figure 5 Gaps in the hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and hepatitis A and B (HAV/HBV) management in referred patients – before and after further evaluation.

ab = antibody; SVR = sustained virological response; non-cohort = non-cohort patients; cohort = cohort patients

The proportion of never HIV antibody screened patients decreased from 21.4% (6/28) to 3.6% (1/28) (p = 0.043) and the proportions with lacking HAV and HBV serology from 67.9% (19/28) to 25% (7/28) (p = 0.001) and from 71.4% (20/28) to 25% (7/28) (p <0.001), respectively.

In decentralised OAT settings such as the Swiss canton Aargau, managing hepatitis C according to guidelines remains a challenge. Since 2017, pangenotypic DAAs are reimbursed in Switzerland without a liver fibrosis stage restriction, which has markedly increased treatment uptake/success and reduced HCV RNA prevalence, though HCV transmission is still ongoing. Although HIV/HCV antibody screening uptake has improved over time, it is still insufficient in OAT patients cared for outside the Argovian OAT cohort. Lack of HCV RNA determination remains a barrier to HCV treatment, especially for non-cohort patients. Adequate HCV management (treatment if HCV RNA positive and yearly screening for infection/reinfection) was more than twice as frequent in cohort than in non-cohort patients. In more than half of the cohort and non-cohort patients, the HAV/HBV serostatus was unknown. Referral to a gastroenterologist or infectious disease specialist substantially improved HCV management, but some patients did not keep the appointment.

The 160 non-cohort patients were mainly from the decentralised setting, i.e., cared for by GPs/psychiatrists in collaboration with pharmacies. The 205 patients enrolled into the Argovian OAT cohort between July 2013 and July 2015 were one half each from the decentralised and the centralised setting [28], whereas the additional 125 patients recruited between August 2015 and August 2018 were mainly from the centralised setting.

Compared with the 2013–2015 baseline data of the Argovian OAT cohort study, HIV/HCV antibody screening uptake has increased in the decentralised setting. The proportion of patients with unknown HIV/HCV serostatus decreased from 35%/34% [28] to 16%/14%. Virtually all cohort patients are screened for HIV/HCV antibodies, because free HIV/HCV antibody rapid testing of fingerstick capillary whole blood is offered at study entry. According to a Swiss-wide analysis in 2015, the proportion of drug users never HCV antibody screened in their life ranged from 1% to 25% [9]. The availability of HCV antibody tests using capillary whole blood from the finger such as dried blood spot testing or the OraQuick® HCV rapid test (Orasure®) [31] has increased screening uptake in different settings worldwide [32–35]. Unfortunately, the OraQuick® HCV antibody rapid tests are only available as packs of 25 tests with a shelf-life of 18 months, complicating their use in settings with a low case load as in Argovia. In contrast to the HIV antibody rapid test, the HCV antibody rapid test is not explicitly mentioned on the list of laboratory tests reimbursed by health insurance in Switzerland [36], and Cominetti et al. reported on problems concerning the reimbursement of the OraQuick HCV rapid test with saliva [9], which is a barrier to the use of this CE-approved test [37].

At 36%, the proportion of HCV antibody positive non-cohort patients with unknown HCV RNA status remains high. To solve this problem and improve linkage-to-care, both the EASL [38] and AASLD HCV guidelines [39] recommend reflex testing for HCV RNA in patients found to be anti-HCV positive. In cohort patients, who, since August 2017, benefit from capillary HCV RNA rapid testing with the GeneXpert® [29], this proportion was reduced to 11%. Even though the GeneXpert® is easily transportable in a passenger car, its use as a point-of-care test is restricted to centralised settings, because it is not cost efficient to visit every GP with only one to three OAT patients. Unfortunately, half of the Argovian OAT prescribers care for only a single OAT patient and >90% have ≤10 OAT patients [28]. In a recently published study, Wlassow et al. showed the proof-of-concept for HCV RNA quantification in dried blood spots with the Xpert® HCV VL test, which could allow capillary HCV RNA testing in a decentralised setting, but not as a point-of-care test. Sensitivity and specificity were high, at 100% (119/119) and 90% (45/50), respectively [40]. In patients with difficult venous access after long-term intravenous drug use, capillary blood tests can facilitate diagnosing chronic HCV infection, monitoring treatment and detecting reinfection [29].

In patients with ever chronic HCV infection, the HCV genotype was frequently unknown (18% in cohort and 41% in non-cohort patients). An underreporting of known genotypes in the decentralised setting cannot be excluded, because the current OAT prescriber (GP or psychiatrist) might be unaware of a HCV genotype determination performed outside of his or her practice. However, in the era of pangenotypic DAAs, HCV genotyping has become dispensable, at least in treatment-naïve non-cirrhotic patients, who, in Switzerland, currently represent about 90% of the population needing treatment [41].

About half of the non-cohort patients with ever chronic HCV infection had no liver fibrosis assessment. In contrast, virtually all cohort patients with ever chronic HCV infection had a liver fibrosis assessment, because free noninvasive liver fibrosis assessment with Fibroscan® was offered to all patients at study entry and follow-up. Up to 2017, DAA treatment in Switzerland was reimbursed only for chronically HCV-infected patients with significant fibrosis or higher liver fibrosis stage (≥F2). Nowadays, the main focus of liver fibrosis assessment is the exclusion of liver cirrhosis (F4), because cirrhotic patients require continued 6-monthly hepatocellular carcinoma screening with abdominal sonography with or without alpha-fetoprotein measurement after successful HCV treatment [38, 42]. Irrespective of the HCV genotype, treatment-naive patients with compensated cirrhosis can now be treated with 8 instead of 12 weeks of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir [43, 44]. As the GeneXpert®, the mobile Fibroscan® is easily transportable in a passenger car, but – due to cost-efficiency considerations – its use is rather restricted to centralised settings. However, in the decentralised setting, the aspartate aminotransferase (AST)-to-platelet ratio index (APRI) [APRI = (AST/upper limit of normal of AST)/platelet count (G/l) ×100], which is easily calculated from routine laboratory test results, can replace the Fibroscan®. At 15% liver cirrhosis (F4) prevalence, an APRI score <1.0 can virtually rule out liver cirrhosis, with a negative predictive value of 94% [45]. For comparison, at 25% liver cirrhosis prevalence, a Fibroscan® result ≤12.5 kPa rules out liver cirrhosis with 95% certainty [46]. The liver cirrhosis (Fibroscan® >12.5 kPa) prevalence in SAMMSU cohort patients receiving their first HCV treatment in 2018 was ~15% [15].

In the 2013–2015 baseline data of the Argovian OAT cohort study, HCV treatment uptake in chronically infected patients was 43% and the SVR rate 75%, both with no difference between the centralised and the decentralised setting. In the era of interferon-free DAA treatment, treatment uptake has increased to 70% in cohort patients (data up to 31 August 2018) and 76% in non-cohort patients (data from September 2018 to September 2019) (p = 0.505). According to the WHO, a treatment uptake of 80% is required to achieve HCV elimination by the year 2030. In patients with known treatment outcome, the SVR rate increased to 94% in cohort patients and 93% in non-cohort patients, although about half of the treatments were interferon based. Treatment outcome was available for all cohort patients, but for only 50% of the non-cohort patients. In only 2 of 14 patients with lacking outcome information, the HCV treatment was in 2018, so that “ongoing treatment” or “treatment completed, but time-point of SVR check-up not yet reached” might be the explanation. In all other cases, it must be assumed that there was either no SVR check or loss of information between the treating HCV specialist and the current OAT prescriber, maybe favoured by repeated changes of the healthcare provider and/or lacking awareness that in the case of failed interferon/ribavirin treatment, the treatment success of an interferon-free DAA treatment remains as high as ≥97% [15]. In the German Hepatitis C Registry, the per-protocol SVR rate of DAA treatment in OAT patients was 96%, but the intention-to-treat SVR rate was lower than in non-OAT patients (85% vs 91%) due to a higher rate of loss to follow-up between the end of treatment and the check for SVR (10% vs 4%) [16]. In an Australian publication, relocation to another healthcare service, difficult venous access or a presumption of cure given the high treatment efficacy were mentioned as possible reasons for the loss to follow-up at the SVR12 time-point [47]. SVR rates ≥97% for DAA treatment in OAT patients with and without continued drug abuse were also observed in the USA [17] and Switzerland [15].

Further evaluation of referred non-cohort patients increased HCV screening uptake to 96% and HCV treatment uptake to 91%, showing the potential for improvement as well as the willingness of OAT patients to accept screening and treatment.

Although for HIV there were no new diagnoses in non-cohort or cohort patients after 2008, HCV transmission continues. HIV seroprevalence was markedly lower than HCV seroprevalence (2% in non-cohort and 6% in cohort patients versus 42% and 51%), with HIV treatment uptake being 100%. Thus, the HIV RNA prevalence can be assumed to be <1% in the total population [15]. Between 2013 –2015 and 2018/2019, HCV treatment uptake increased from 43% to 70–75%, resulting in an HCV RNA prevalence reduction from 52% to 24–35% among HCV antibody positives and from 28% to 8–11% in the total population. The 10-fold higher HCV RNA prevalence compared with HIV might in part explain the ongoing HCV transmission. In addition, HCV is approximately 10 times more infectious than HIV through blood-to-blood contact [48], enabling its spread not only through needle and syringe sharing, but also via other contaminated equipment such as water, spoons and filters [49], as well as sharing of snorting straws [50].

Another reason for higher HCV than HIV RNA positivity might be the lower awareness of HCV compared with HIV, resulting in reduced levels of care and thus higher rates of untreated patients.

As long as HCV transmission is ongoing, regular screening is essential for early detection and treatment of new and re-infections. Compared with the 2013–2015 baseline data of the Argovian OAT cohort, the proportion of HCV antibody negatives with last HCV antibody test ≤1 year ago has increased from 23% [28] to 91% in cohort patients and 38% in non-cohort patients. In December 2009, about 50% of the HCV negative patients in three centralised OAT programmes in St Gallen had a current test [51]. In the Ukraine in 2014/2015, 22% of people who inject drugs had a recent test (in the past 12 months) [52].

Compared with the 2013–2015 baseline data of the Argovian OAT cohort, the proportion of HCV antibody positive RNA negatives with last HCV RNA test ≤1 year ago has increased from 40% [28] to 73% in cohort patients and 58% in non-cohort patients, which may in part reflect recent treatment.

About 30% of the cohort patients already had at least one follow-up and thus additional test opportunities. The proportion with adequate regular HCV antibody or HCV RNA screening might be overestimated in cohort patients because for them, the reference date was the last follow-up, which was not always performed each year as intended. Invalid cell phone numbers and patients not showing up complicate follow-up.

Compared with the 2013–2015 baseline data, the availability of HAV or interpretable HBV serology in Argovian OAT cohort study patients has not improved. Both remain low, at below 50%. In a study in Irish GPs, 66% of OAT patients were screened for HBV [53] and in the three centralised OAT programmes in St Gallen, 90% had HAV/HBV serology [51]. Whereas for both cohort and non-cohort patients, 38% had HAV serology, the proportion with interpretable HBV serology was significantly lower in non-cohort patients (24% vs 45%), because, with respect to immunity, the HBV serology results for non-cohort patients were interpretable in only 54%. There seem to be gaps of knowledge that should be closed.

Another barrier to performing a HAV/HBV serology might be the necessity of a venous blood draw. For a “test and vaccinate” approach, rapid tests using capillary whole blood would be an optimal solution. An anti-HAV IgG test is already CE approved. For HBV, there is only a CE-approved HBs Ag rapid test using capillary whole. However, an HBV panel rapid test including anti-HBs, HBs Ag and anti-HBc is currently under development and might even provide HIV and HCV antibody rapid testing in the same run.

In cases having available HAV serology, 42% of the cohort and 57% of the non-cohort patients were not immune and thus in need of vaccination. In cases with interpretable HBV serology, 30% of the cohort and 18% of the non-cohort patients were not immune and thus in need of vaccination.

In Switzerland, 60% of OATs are prescribed by GPs, but so far only infectious disease specialists, gastroenterologists and addiction specialists with experience in HCV treatment are allowed to prescribe DAAs. Referral of OAT patients to outpatient clinics of tertiary care hospitals is a barrier to HCV treatment [54], because these patients often have difficulty keeping appointments. Since spring 2019, the Hepcare project initiated by the Swiss Hepatitis Strategy allows GPs and psychiatrists to treat chronic hepatitis C patients in their practices under the supervision of an infectious disease specialist or gastroenterologist, who prescribes the DAA treatment in the framework of a council based on the patient’s medical records. An Australian randomised controlled study recently showed that HCV treatment uptake is higher in GPs’ practices than in outpatient clinics of the local hospitals (75% vs 34%), but treatment success is the same [47]. Increased retention in care halved the average cost of treatment initiation [55]. Since May 2019, GPs in France are also allowed to prescribe DAAs, which goes along with simplified HCV treatment guidelines aiming at HCV elimination by 2030 [56].

However, a survey in Australian GPs showed that although 53% were interested in prescribing DAAs, 72% continued to refer all patients to specialists [57]; 55% were unsure if people who currently inject drugs were eligible for treatment and 14% incorrectly identified HCV antibody positivity alone as diagnostic for current infection. Higher caseload (≥10 HCV patients) was positively correlated with better HCV knowledge [57]. Of note, “low caseload” is a characteristic of the Argovian GPs, with half of them caring for only one OAT patient and >90% for ≤10 OAT patients [28], and HCV management was worse in the decentralised than the centralised setting [28].

Feasibility of HIV/HCV antibody rapid testing by the GP has been demonstrated earlier [28]. However, awareness and knowledge of GPs with respect to adequate testing [25], guidelines urging for treatment of all patient with chronic hepatitis [38, 39] and availability of new, well tolerated and easy to use DAAs [42] still needs to be improved.

Since our study included only OAT patients, results cannot be generalised to all drug users. However, investigating the HCV management in 160 non-cohort patients in addition to the 330 cohort patients markedly increased the representativeness of the data. Nonetheless, for about half of the current Argovian OAT patients information about their HCV management is still lacking. Because of a response bias towards GPs/psychiatrists with increased interest in hepatitis C, it must be assumed that the HCV management in non-responders is even worse than that in the non-cohort patients enrolled into our study. Another ~170 patients live in the canton Aargau, but receive their OAT in another canton, and have therefore not been considered for this study.

A relatively high fluctuation rate in OAT programmes (up to one third) [15], i.e. repeated changes of the healthcare provider, might have led to a loss of information regarding the management of HCV/HIV/HAV/HBV and thus to an underestimation of the quality of care. In the future, documentation of the HCV management in the FOPH-supported platform substitution-online.ch could overcome this problem. This platform could also help to remind OAT providers of the yearly screening according to the FOPH guidelines published in March 2019. It is already used by 20 of the 26 Swiss cantons, with another 5 cantons being interested.

Data of the Argovian OAT cohort study contribute to the SAMMSU cohort study, which provides a nationwide picture of the HCV management in drug substitution programmes [15].

A good collaboration with the (deputy) cantonal physician and engaged healthcare workers in the OAT programmes / addiction clinics are a prerequisite to transfer our results to other settings.

Regarding HCV elimination in OAT patients by 2030, case-finding and regular screening for new and re-infections remain a challenge, especially for non-cohort patients in a decentralised setting. Documentation of the HCV sero- and RNA status of each OAT patient by the cantonal physician and a yearly HCV screening reminder sent to the OAT prescriber combined with capillary HCV antibody and HCV RNA testing by the OAT prescriber, general practitioner or the pharmacy might facilitate the implementation of the FOPH guidelines. DAA prescription directly by the OAT prescriber could increase awareness and improve linkage to care.

The appendix is available as a separate file from: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20317.

The study “Management of hepatitis C in drug substitution programmes – canton Aargau” has been financially supported by the Cantonal Hospital Aarau, the Swisslos-Fonds, Axonlab®, Cepheid®, the Hugo und Elsa Isler-Fonds, Roche, MSD and Gilead.

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.

1WHO. Fact-sheet Hepatitis C (9 July 2019). Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hepatitis-c (Accessed: 2020 January 13)

2 Grebely J , Page K , Sacks-Davis R , van der Loeff MS , Rice TM , Bruneau J , et al.; InC3 Study Group. The effects of female sex, viral genotype, and IL28B genotype on spontaneous clearance of acute hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2014;59(1):109–20. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.26639

3 Evon DM , Stewart PW , Amador J , Serper M , Lok AS , Sterling RK , et al. A comprehensive assessment of patient reported symptom burden, medical comorbidities, and functional well being in patients initiating direct acting antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C: Results from a large US multi-center observational study. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0196908. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196908

4 Thein HH , Yi Q , Dore GJ , Krahn MD . Estimation of stage-specific fibrosis progression rates in chronic hepatitis C virus infection: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. Hepatology. 2008;48(2):418–31. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.22375

5 Edlin BR . Perspective: test and treat this silent killer. Nature. 2011;474(7350):S18–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/474S18a

6 Aaron S , McMahon JM , Milano D , Torres L , Clatts M , Tortu S , et al. Intranasal transmission of hepatitis C virus: virological and clinical evidence. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(7):931–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1086/591699

7 Degenhardt L , Peacock A , Colledge S , Leung J , Grebely J , Vickerman P , et al. Global prevalence of injecting drug use and sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of HIV, HBV, and HCV in people who inject drugs: a multistage systematic review. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(12):e1192–207. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30375-3

8Zahnd C, Brezzi M, Bertisch B, Giudici F, Keiser O. Analyse de Situation des Hépatites B et C en Suisse. 2017. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=2ahUKEwiC_KLc0YLnAhXDb1AKHWdQAW0QFjABegQIBxAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.bag.admin.ch%2Fdam%2Fbag%2Fde%2Fdokumente%2Fmt%2Fforschungsberichte%2Fsituationsanalyse-hepatitis-bericht.pdf.download.pdf%2Fsituationsanalyse-hepatitis-bericht-de.pdf&usg=AOvVaw03m8hsizPqQkqZgnEfZfY_

9Cominetti F, Simonson T, Dubois-Arber F, Gervasoni JP, Schaub M, Monnat M. Analyse der Hepatitis-C-Situation bei den drogenkonsumierenden Personen in der Schweiz. Lausanne: Institut universitaire de médecine sociale et préventive; 2015. (Raisons de santé 234b) Available from: https://www.iumsp.ch/Publications/pdf/rds234b_de.pdf

10 Richard JL , Schaetti C , Basler S , Mäusezahl M . The epidemiology of hepatitis C in Switzerland: trends in notifications, 1988-2015. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14619. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14619

11Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. (1 July 2019). Substitutionsgestützte Behandlungen bei Opioidabhängigkeit. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/gesund-leben/sucht-und-gesundheit/suchtberatung-therapie/substitutionsgestuetzte-behandlung.html

12 Bruggmann P , Blach S , Deltenre P , Fehr J , Kouyos R , Lavanchy D , et al. Hepatitis C virus dynamics among intravenous drug users suggest that an annual treatment uptake above 10% would eliminate the disease by 2030. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14543.

13 Zeuzem S . Hepatitis-C-Therapie: State of the Art 2018 [Treatment of Hepatitis C: State of the Art 2018]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2018;143(24):1784–8. Article in German. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0591-5916

14 Lawitz E , Mangia A , Wyles D , Rodriguez-Torres M , Hassanein T , Gordon SC , et al. Sofosbuvir for previously untreated chronic hepatitis C infection. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(20):1878–87. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1214853

15 Bregenzer A , Bruggmann P , Castro E , Moriggia A , Rothen M , Thurnheer MC , et al. Schweizer OAT-Programme auf ihrem Weg zur HCV-Elimination – Die SAMMSU-Kohorte. Suchtmedizin. 2019;21(2):75–90.

16 Christensen S , Buggisch P , Mauss S , Böker KHW , Schott E , Klinker H , et al. Direct-acting antiviral treatment of chronic HCV-infected patients on opioid substitution therapy: Still a concern in clinical practice? Addiction. 2018;113(5):868–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14128

17 Gayam V , Tiongson B , Mandal AK , Garlapati P , Pan C , Mohanty S . Real-world study of hepatitis C treatment with direct-acting antivirals in patients with drug abuse and opioid agonist therapy. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2019;54(5):646–55. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2019.1617893

18 Hajarizadeh B , Cunningham EB , Reid H , Law M , Dore GJ , Grebely J . Direct-acting antiviral treatment for hepatitis C among people who use or inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(11):754–67. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(18)30304-2

19 Grebely J , Dalgard O , Conway B , Cunningham EB , Bruggmann P , Hajarizadeh B , et al.; SIMPLIFY Study Group. Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir for hepatitis C virus infection in people with recent injection drug use (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, single-arm, phase 4, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(3):153–61. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30404-1

20 Cunningham EB , Amin J , Feld JJ , Bruneau J , Dalgard O , Powis J , et al.; SIMPLIFY study group. Adherence to sofosbuvir and velpatasvir among people with chronic HCV infection and recent injection drug use: The SIMPLIFY study. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;62:14–23. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.08.013

21Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. (27 April 2017.) BAG erweitert Vergütung von Medikamenten gegen Hepatitis C. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/das-bag/aktuell/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-66508.html

22Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. (25 September 17.) Hepatitis C: Uneingeschränkte Vergütung der neuen Arzneimittel für alle Betroffenen. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/de/home/das-bag/aktuell/medienmitteilungen.msg-id-68158.html

23World Health Organization. (May 2016.) Combating hepatitis B and C to reach elimination by 2030 - Advocacy brief. Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/206453/1/WHO_HIV_2016.04_eng.pdf (Cited 2020 January 14.)

24Swiss Hepatitis Strategy 2014-2030. Available from: https://www.hepatitis-schweiz.ch/files/Dokumente/PDF/Process_Paper_14_02_2019.pdf (Cited 2020 January 14.)

25Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. (03/2019) Hepatitis C bei Drogenkonsumierenden: Richtlinien mit settingspezifischen Factsheets. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/mt/infektionskrankheiten/hepatitis-c/richtlinien-hepatitis-c-drogen.pdf.download.pdf/richtlinien-hepatitis-c-drogen-de.pdf (Cited 2020 January 14.)

26 Bruggmann P , Broers B , Meili D . Hepatitis C-Therapie bei Patienten unter Opioidsusbstitution. Empfehlungen der Schweizerischen Gesellschaft für Suchtmedizin (SSAM). Schweiz Med Forum. 2007;7:916–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/smf.2007.06330

27 Grebely J , Robaeys G , Bruggmann P , Aghemo A , Backmund M , Bruneau J , et al.; International Network for Hepatitis in Substance Users. Recommendations for the management of hepatitis C virus infection among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2015;26(10):1028–38. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.07.005

28 Bregenzer A , Conen A , Knuchel J , Friedl A , Eigenmann F , Näf M , et al. Management of hepatitis C in decentralised versus centralised drug substitution programmes and minimally invasive point-of-care tests to close gaps in the HCV cascade. Swiss Med Wkly. 2017;147:w14544.

29 Bregenzer A , Warmann N , Ottiger C , Fux CA . Rapid point-of-care HCV RNA quantification in capillary whole blood for diagnosing chronic HCV infection, monitoring treatment and detecting reinfection. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019;149:w20137. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20137

30Offizielle Website der nationalen Substitutionsstatistik, 2016-2020). Available from: https://www.substitution.ch/de/jahrliche_statistik.html&year=2018&canton=ag (Cited: 2020 June 14.)

31 Lee SR , Kardos KW , Schiff E , Berne CA , Mounzer K , Banks AT , et al. Evaluation of a new, rapid test for detecting HCV infection, suitable for use with blood or oral fluid. J Virol Methods. 2011;172(1-2):27–31. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2010.12.009

32 McLeod A , Weir A , Aitken C , Gunson R , Templeton K , Molyneaux P , et al. Rise in testing and diagnosis associated with Scotland’s Action Plan on Hepatitis C and introduction of dried blood spot testing. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2014;68(12):1182–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-204451

33European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Hepatitis B and C testing strategies in healthcare and community settings in the EU/EEA –A systematic review. Stockholm: ECDC; 2018

34 Fourati S , Feld JJ , Chevaliez S , Luhmann N . Approaches for simplified HCV diagnostic algorithms. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(Suppl 2):e25058. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/jia2.25058

35 Chevaliez S . Strategies for the improvement of HCV testing and diagnosis. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2019;17(5):341–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/14787210.2019.1604221

36Bundesamt für Gesundheit BAG. (April 2020) Analysenliste vom 30.04.2020. Available from: https://www.bag.admin.ch/dam/bag/de/dokumente/kuv-leistungen/leistungen-und-tarife/Analysenliste/analysenliste-gesamt-01042020.pdf.download.pdf/Analysenliste%20vom%2001.04.2020.pdf (Cited: 2020 June 14.)

37Orasure (21 January 2013) Product information: OraQuick® HCV Rapid Antibody Test, Available from: https://www.orasure.com/products-infectious/products-infectious-oraquick-hcv.asp (Cited: 2020 June 14.)

38 Pawlotsky J-M , Negro F , Aghemo A , Berenguer M , Dalgard O , Dusheiko G , et al.; European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu; European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Recommendations on Treatment of Hepatitis C 2018. J Hepatol. 2018;69(2):461–511. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.026

39 Ghany MG , Morgan TR ; AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2019 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2020;71(2):686–721. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.31060

40 Wlassow M , Poiteau L , Roudot-Thoraval F , Rosa I , Soulier A , Hézode C , et al. The new Xpert HCV viral load real-time PCR assay accurately quantifies hepatitis C virus RNA in serum and whole-blood specimens. J Clin Virol. 2019;117:80–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcv.2019.06.007

41 Müllhaupt B , Semela D , Ruckstuhl L , Magenta L , Clerc O , Torgler R , et al. Real World Evidence of the Effectiveness and Clinical Practice Use of Glecaprevir plus Pibrentasvir in Patients with Chronic Hepatitis C Genotypes 1 to 6: The MYTHEN Study. SGG-SGVC-SASL-GESKES Annual Meeting. Interlaken. September 12th–13th, 2019. Oral presentation O23. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019;149(Suppl 240):S7. Available from https://smw.ch/fileadmin/content/supplements/SMW_Suppl_240.pdf.

42Moradpour D, Fehr J, Semela D, Rauch A, Müllhaupt B. Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C - August 2018 Update SASL-SSI Expert Opinion Statement. Available from: https://www.sginf.ch/files/sasl-ssi_eos_aug2018.pdf

43 Brown RS, Jr , Buti M , Rodrigues L , Chulanov V , Chuang WL , Aguilar H , et al. Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for 8 weeks in treatment-naïve patients with chronic HCV genotypes 1-6 and compensated cirrhosis: The EXPEDITION-8 trial. J Hepatol. 2020;72(3):441–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.10.020

44American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Infectious Diseases Society of America. HCV Guidance: Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C. Available from: www.hcvguidelines.org. Last updated 6 November 2019.

45 Shaheen AA , Myers RP . Diagnostic accuracy of the aspartate aminotransferase-to-platelet ratio index for the prediction of hepatitis C-related fibrosis: a systematic review. Hepatology. 2007;46(3):912–21. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/hep.21835

46 Castéra L , Vergniol J , Foucher J , Le Bail B , Chanteloup E , Haaser M , et al. Prospective comparison of transient elastography, Fibrotest, APRI, and liver biopsy for the assessment of fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(2):343–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2004.11.018

47 Wade AJ , Doyle JS , Gane E , Stedman C , Draper B , Iser D , et al. Outcomes of treatment for hepatitis C in primary care compared to hospital-based care: a randomised controlled trial in people who inject drugs. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70(9):1900–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciz546

48 Coutinho RA . HIV and hepatitis C among injecting drug users. BMJ. 1998;317(7156):424–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.317.7156.424

49 Hagan H , Thiede H , Weiss NS , Hopkins SG , Duchin JS , Alexander ER . Sharing of drug preparation equipment as a risk factor for hepatitis C. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(1):42–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.1.42

50 Fernandez N , Towers CV , Wolfe L , Hennessy MD , Weitz B , Porter S . Sharing of Snorting Straws and Hepatitis C Virus Infection in Pregnant Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;128(2):234–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001507

51 Witteck A , Schmid P , Hensel-Koch K , Thurnheer MC , Bruggmann P , Vernazza P ; Swiss Hepatitis C and HIV Cohort Studies. Management of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in drug substitution programs. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13193. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2011.13193

52 Iakunchykova O , Meteliuk A , Zelenev A , Mazhnaya A , Tracy M , Altice FL . Hepatitis C virus status awareness and test results confirmation among people who inject drugs in Ukraine. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:11–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.03.022

53 Murtagh R , Swan D , O’Connor E , McCombe G , Lambert JS , Avramovic G , et al. Hepatitis C Prevalence and Management Among Patients Receiving Opioid Substitution Treatment in General Practice in Ireland: Baseline Data from a Feasibility Study. Interact J Med Res. 2018;7(2):e10313. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2196/10313

54 Litwin AH , Drolet M , Nwankwo C , Torrens M , Kastelic A , Walcher S , et al. Perceived barriers related to testing, management and treatment of HCV infection among physicians prescribing opioid agonist therapy: The C-SCOPE Study. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26(9):1094–104. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/jvh.13119

55 Palmer AY , Wade AJ , Draper B , Howell J , Doyle JS , Petrie D , et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of primary versus hospital-based specialist care for direct acting antiviral hepatitis C treatment. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;76:102633; Epub ahead of print. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.102633

56 Loustaud-Ratti V , Debette-Gratien M , Carrier P . European Association for the Study of the Liver and French hepatitis C recent guidelines: The paradigm shift. World J Hepatol. 2018;10(10):639–44. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4254/wjh.v10.i10.639

57 Wade A , Draper B , Doyle J , Allard N , Grinzi P , Thompson A , et al. A survey of hepatitis C management by Victorian GPs after PBS-listing of direct-acting antiviral therapy. Aust Fam Physician. 2017;46(4):235–40.

The study “Management of hepatitis C in drug substitution programmes – canton Aargau” has been financially supported by the Cantonal Hospital Aarau, the Swisslos-Fonds, Axonlab®, Cepheid®, the Hugo und Elsa Isler-Fonds, Roche, MSD and Gilead.

There is no conflict of interest for any of the authors.