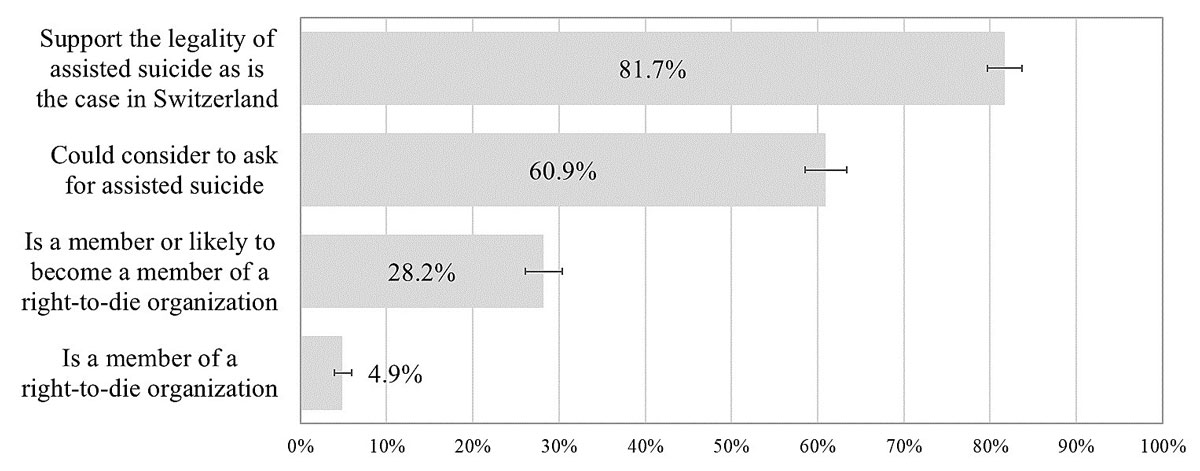

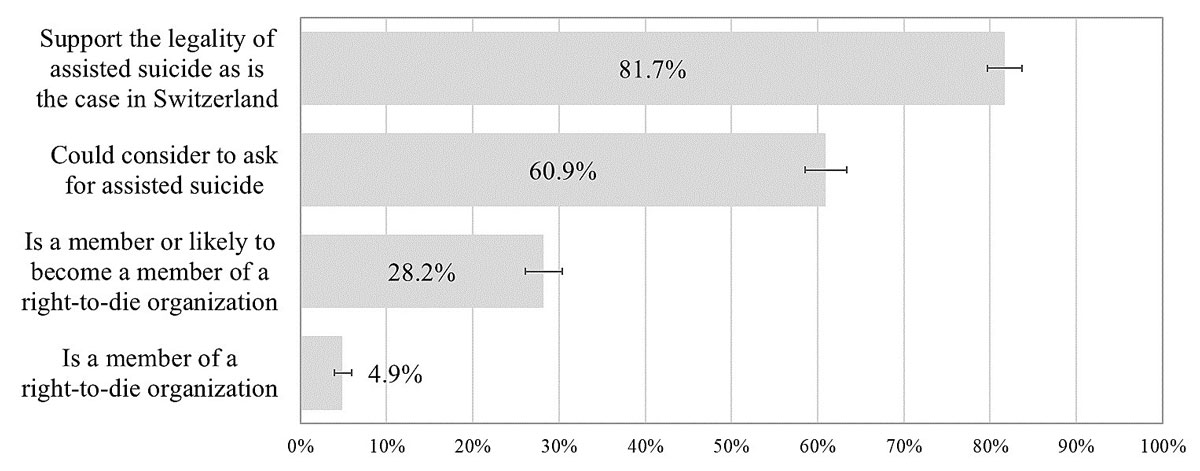

Figure 1 Attitudes and behaviours towards assisted suicide. Adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval, SHARE 2015 (n = 2168).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20275

Switzerland has a longer experience of the legal practice of assisted suicide than any other country. Assisted suicide is not very strictly regulated in Switzerland compared to other places like, for example, Oregon, which enacted the Death with Dignity Act in 1997. Assisted suicide is defined as the intentional provision to a competent person of help to commit suicide by providing a lethal drug for self-administration [1]. In contrast, euthanasia refers to the intentional killing of a competent person upon his/her voluntary request, usually performed by a physician [1]. Euthanasia is forbidden in Switzerland, whereas assisted suicide is legal. Assisted suicide is mainly regulated through article 115 of the Swiss Penal Code of 1937, which stipulates that assisting a person to commit suicide is not punishable as long as it is not performed for selfish reasons (e.g., obtaining inheritance or making profits) and as long as the person seeking suicide has decisional capacity.

Since the 1980s, not-for-profit right-to-die organisations advocating the right to self-determination in death have assisted individuals in suicide under the regulation of article 115. Any interested person can become a member of a right-to-die organisation for a small fee, and membership gives free access to the organisation’s services in due course. Right-to-die organisations provide help with any medical, administrative and social procedures related to the completion of assisted suicide [2]. This essentially means they, among other things, assist in obtaining the barbiturate, document the entire procedure and accompany the assisted suicide-seeking person and her/his family. The eligibility criteria for assisted suicide are defined by the internal regulations of the association and include the person being capable of discernment and expressing a persistent and repeated desire to die.

Almost all assisted suicides in Switzerland are supported by a right-to-die organisation [3, 4]. In 2016, assisted suicides represented 1.4% of all deaths in Switzerland [5], and of the 928 people who died by assisted suicide, 86% were aged 65 years or older. Deaths by assisted suicide in Switzerland have been systematically recorded since 2009, and their number more than tripled between 2009 and 2016.

Assisted suicide in Switzerland is subject only to relatively “open” regulation [6]. This legal situation has been challenged several times by Swiss parliamentarians asking for the creation of a more detailed legal framework to regulate the practice of assisted suicide [7]. However, after several unsuccessful attempts to expand the law regarding assisted suicide, in 2011 the Federal Council made the decision to maintain the status quo, stating that the current regulation was sufficient to prevent potential abuses of the practice of assisted suicide [2]. The government claimed that the various legal instruments in force, as well as the medical code of ethics, mean administering criminal, administrative or civil sanctions would already be possible in all cases of abuse. Accordingly, the system was claimed to have the advantage of ensuring a balance between respect for the right to self-determination and the State's duty to protect all citizens [7]. This view, however, is highly controversial [8]. Comparative data from various nations suggest that the current regulation of assisted suicide in Switzerland may have played a role in the increase in the number of assisted deaths that has occurred over the last decade [9].

Since this decision by the Federal Council, support for assisted suicide in the general population has – to the best of our knowledge – not been assessed. Most studies on the topic have focused on the occurrence of deaths by assisted suicide [10–15] and only a few have analysed public opinions regarding the practice of assisted suicide in Switzerland. One study, conducted in 2009, showed that the majority of people aged 15 and over in Switzerland consider euthanasia and assisted suicide morally acceptable, and that they largely agree with the legality of these practices [4]. However, the levels of moral and legal agreement often vary depending on the health status, medical condition and prognosis of the patient requesting a voluntary ending to their life, for example whether or not the patient is terminally ill, has aged-related comorbidities or has an aged-related neurodegenerative disorder, among other considerations [4]. According to another study, from 2010, one third of adults aged 15 and over in Switzerland stated that they might consider asking for assisted suicide if they had an incurable disease [16].

Switzerland has three main linguistic regions: a German-, a French- and an Italian-speaking region. These regions differ culturally as well as linguistically, as shown by, for example, distinct attitudes towards work and different voting behaviours across linguistics regions [17]. Culture might also shape the way people consider assisted suicide, since the conception of death and dying is heavily influenced by culture [18].

Views on euthanasia and assisted suicide may also be affected by personal experiences with the care of terminally ill relatives or close friends and/or by being a surrogate in medical decision-making. Non-professionals involved in the regular care of seriously ill individuals experience a psychological and physical burden and can find participating in social activities challenging [19]. In addition, making medical decisions on behalf of a loved one can also cause negative emotional stress [20]. People who have been closely involved in end-of-life (EOL) situations may be more inclined towards wanting their loved ones to avoid these experiences. To this end, they may be more likely to engage in EOL planning, for example by completing advance directives [21], but also by considering the possibility of assisted suicide.

The practice of euthanasia and assisted suicide is controversial and raises many concerns, including the risk of continuous expansion of the criteria permitting access to these practices, which is often referred to as the “slippery slope” problem, or the risk of outright abuse [22]. In ageing societies that face important social and economic challenges, assisted suicide and/or euthanasia may be viewed as a tool to reduce the social and cost-related pressures associated with the potential care requirements of sick older persons. In such a context, there may be a risk that people seek assisted suicide and/or euthanasia to avoid feeling guilty about becoming a burden to their family and/or to society [23]. Vulnerable population groups, such as older persons, those with lower levels of education or individuals without relatives to care for them, may be especially exposed to such pressures when becoming ill [24], even though existing data on assisted suicide and/or euthanasia do not seem to provide much support for the hypothesis of widespread abuse or misuse of these practices [25].

Population-based data on behaviour regarding membership of right-to-die organisations are still lacking, as are data on attitudes towards assisted suicide following the Swiss government’s renewed decision not to expand assisted suicide regulation. Our study explores assisted suicide-related attitudes and behaviour and their determinants in a nationally representative sample of adults aged 55 and over in Switzerland. Firstly, we describe older adults’ general support for the practice of assisted suicide, whether or not they would consider assisted suicide as an EOL option for themselves, and their behaviour in terms of current or intended future membership of a right-to-die organisation. Secondly, we investigate sociodemographic patterning of attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide and how these are shaped by culture and previous experience as a healthcare proxy.

Our data come from Swiss participants in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) from 2015 [26]. Specifically, our outcomes of interest and our selected explanatory variables originate from a paper-and-pencil questionnaire aimed at exploring individual preferences, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours towards EOL planning [27]. This questionnaire was developed by the authors and administrated as part of the sixth wave of SHARE in Switzerland. SHARE is a longitudinal, interdisciplinary and cross-national data infrastructure that comprises individual-level information on the health, socio-economic status, social and family networks and other life circumstances of persons aged 50 and over from 27 European countries and Israel. Overall, 2806 respondents participated in the face-to-face interview of wave 6 (2015) of SHARE in Switzerland, and 94% of those respondents also filled out our 15-page self-completion EOL questionnaire. At the time of sampling, the Swiss SHARE study was designed to be nationally representative of community-dwelling individuals aged 50 and older and their partners. However, as the Swiss SHARE sample was last refreshed in 2011, we only retained adults aged 55 and over for our analyses, since respondents aged 50–54 in 2015 could only enter SHARE as partners and are therefore not representative of the general population aged 50–54. Our final analytical sample consists of 2549 respondents.

Our study considers five outcomes based on four questions about attitudes and behaviours towards assisted suicide. We asked respondents (1) whether or not they support the legality of assisted suicide, as is the case in Switzerland (yes, no) and (2) whether or not they could imagine circumstances under which they would consider requesting assisted suicide for themselves (yes, no). We constructed a measure of (3) current or planned future membership of a right-to-die organisation by grouping respondents who declared either that they (a) were already a member of a right-to-die organisation or (b) would “very likely” or “for sure” become a member of such an organisation some day in the future. Finally, we also present data on (4) current membership (yes, no) and, for those who are not currently members, (5) intended future membership of a right-to-die organisation (“for sure” and “very likely” vs “not very likely” and “certainly not”) separately. We refer to outcomes (1), (2), (3), and (5) as “attitudes” towards assisted suicide while considering outcome (4) a “behaviour”.

The key independent variables of our analyses are related to the respondents’ sociodemographic, cultural and experiential characteristics. The sociodemographic characteristics included in our models are gender, age group (55–64; 65–74; 75+), education level, living with a partner in the same household (yes, no), and having living children (yes, no). Education level was measured according to the ISCED1997 classification [28] and grouped into three categories: levels 0–2 (pre-primary, primary and lower secondary education), labelled “low education”; levels 3–4 (upper and post-secondary education), labelled “medium education”, and levels 5–6 (first and second stages of tertiary education), labelled “high education”. Cultural characteristics refer to the interview language (German, French or Italian), which is related to the three Swiss linguistic regions. Language is commonly used as a proxy for cultural differences between the linguistic regions in Switzerland [29, 30]. In addition, we also included the respondents’ place of residence (urban vs rural areas) as an explanatory variable in the model. Moreover, we used the respondents’ religiosity, as measured through their self-reported practice of prayer, as an explanatory variable, distinguishing individuals who never pray from those who pray at least occasionally. Experiential characteristics included the respondents’ health, as measured by their self-rated health status (poor/fair vs good/very good/excellent) and their self-reported limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) (no limitation vs 1+ limitation(s)). We also included experience as a healthcare proxy, measured as previous involvement in making medical decisions on behalf of a relative or friend.

Across the 15 variables used in our analysis, proportions of missing values ranged from 0% to 7% across items, with 80% of all cases being complete, with no missing items (supplementary table S1 in appendix 1 details the distribution of missing values). Since Little’s tests [31] rejected the null hypothesis that the missing values were missing completely at random (MCAR), multiple imputations by chained equations were used to handle the presence of missing values in our data. Two hundred imputed datasets were computed in order to calculate asymptotically correct standard errors of our estimates. The imputation equations were based on all the sociodemographic characteristics, health status and linguistic region. Parameter estimates and standard errors of the logistic regression models based on the imputed data sets were calculated using Rubin’s formulas [32]. These estimates and standard errors, and the resulting patterns of statistical significance of the different logistic regression models, were largely comparable between the analyses based on the imputed data and those based on the corresponding complete case analyses. However, statistical precision was somewhat higher when using the imputed data.

We first present weighted proportions of selected characteristics of our final analytical sample based on the imputed data. Second, we show the weighted prevalences of our outcomes of interest along with their 95% confidence intervals. Third, associations between attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide and our independent variables are explored using multivariable logistic regression models. We computed the corresponding average partial effects (APEs) to facilitate the interpretation of the results of the logistic regression models. APEs describe how the average conditional probability of outcome Y given explanatory variables X, P(Y = 1 given X), changes with a one unit change (say, from zero to one in the case of a dummy explanatory variable) in a given independent variable X while holding all other variables at their observed values. Estimated standard errors account for clustering at the household level to correct for potential unobserved dependencies between two observations coming from the same household. Data management and all statistical analyses were conducted using Stata SE 15.0 (StataCorp LLC, College Station).

Our study obtained ethical approval number 66/14 from the ethics committee of the canton of Vaud, Switzerland, in March 2014.

Table 1 presents the weighted respondent characteristics for our analytical sample. Half of our respondents were women (50%) and half were aged 55–64 (49.1%). A large majority had a medium education level (69.7%), lived with their partner (71.6%), had children (82.4%) and lived in the German-speaking part of Switzerland (75%). Most of our respondents declared themselves to be in good to excellent health (82.3%); only 6.2% reported having at least one limitation in their activities of daily living. Finally, 18.3% of our respondents had previous experience as a healthcare proxy.

Table 1 Main characteristics of the analytical sample, adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, SHARE 2015 (n = 2168).

| Weighted proportion (%) | (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||

| Women | 50.0 | (47.9,52.0) |

| Age groups | ||

| 55–64 | 49.1 | (46.5,51.7) |

| 65–74 | 28.3 | (26.2,30.4) |

| 75+ | 22.6 | (20.7,24.6) |

| Education level | ||

| Low education | 12.9 | (11.3,14.4) |

| Medium education | 69.7 | (67.5,71.9) |

| High education | 17.5 | (15.6,19.4) |

| Partner living in household | 71.6 | (69.3,73.9) |

| Having children | 82.4 | (80.3,84.4) |

| Cultural characteristics | ||

| Urban area | 47.0 | (44.4,49.7) |

| Linguistic region | ||

| German-speaking | 75.0 | (72.7,77.3) |

| French-speaking | 22.4 | (20.2,24.6) |

| Italian-speaking | 2.6 | (1.8,3.4) |

| Practice of prayer | 67.7 | (65.3,70.1) |

| Experiential characteristics | ||

| Self-rated health: (very) good/excellent | 82.3 | (80.5,84.2) |

| 1+ limitations in activities of daily living | 6.2 | (5.1,7.3) |

| Participation in making medical decisions for relative/friend | 18.3 | (16.6,20.4) |

Figure 1 shows the weighted prevalences of different attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide among adults aged 55+ in Switzerland. A large majority (81.7%) of our respondents supported the legality of assisted suicide, as is the case in Switzerland, and 60.9% of respondents reported that they would consider asking for assisted suicide under certain circumstances. In addition, 28.2% of respondents reported either that they were a member of a right-to-die organisation or that they were likely become a member of such an organisation some day in the future. 4.9% of respondents were already members of such an organisation at the time of the survey.

Figure 1 Attitudes and behaviours towards assisted suicide. Adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, weighted percentage and 95% confidence interval, SHARE 2015 (n = 2168).

Table 2 presents the APEs, estimated from the multivariable logistic regression models, of the attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide stratified by the sociodemographic, cultural and experiential characteristics of the respondents. Compared to men, women were more likely to already be (APE: 2.2, p <5%) or to plan to become (APE: 4.3, p <5%) members of a right-to-die organisation. Older respondents (75+) had – on average – more negative attitudes towards assisted suicide than less old adults (55–64), but only the associations with potential use of assisted suicide (APE: −6.2, p <5%) and potential future membership of a right-to-die organisation (APE: −8, p <0.1%) are statistically significant at the 5% level. On the other hand, older respondents were more likely to already be members of a right-to-die organisation (APE: 6.7, p <0.1%). Respondents aged 65–74 displayed more positive attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide than those aged 55–64. However, in this age group only the associations with support for assisted suicide (APE: 4.4, p <5%) and current (APE: 2.4, p <5%) or potential future (APE: 4.9, p <5%) membership of a right-to-die organisation are statistically significant.

Table 2 Average partial effects (APEs) based on logistic regressions of attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide by sociodemographic and family characteristics, self-rated health status, practice of prayer, experience as a healthcare proxy and geographical location in adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, SHARE 2015.

| Support the legality of assisted suicide as is the case in Switzerland | Could consider asking for assisted suicide | Is a member or likely to become a member of a right-to-die organisation | Is a member of a right-to-die organisation | Is likely to become a member of a right-to-die organisation† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Women | 1.2 (−1.8,4.1) |

-1.3 (−5.3,2.6) |

4.3*

(0.7,8.0) |

2.2*

(0.5,3.9) |

2.4 (−1.1,5.9) |

| Age groups | |||||

| 55–64 (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| 65–74 | 4.4*

(0.5,8.3) |

0.8 (-4.1,5.7) |

4.9*

(0.4,9.4) |

2.4*

(0.3,4.5) |

2.8 (-1.5,7.2) |

| 75+ |

−3.70 (−8.4,1.0) |

−6.2*

(−11.9,-0.6) |

−2.0 (−7.2,3.2) |

6.8***

(3.5,10.0) |

−8.0***

(−12.6,−3.3) |

| Education level | |||||

| Low education (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Medium education | 6.4*

(1.0,11.8) |

9.6**

(3.2,16.1) |

10.9***

(5.6,16.2) |

4.3***

(2.4,6.1) |

8.0**

(3.1,13.0) |

| High education | 12.7***

(6.4,18.9) |

17.2***

(9.5,24.9) |

17.3***

(10.3,24.3) |

6.8***

(3.4,10.2) |

13.3***

(6.7,20.0) |

| Partner living in household | 0.4 (−3.5,4.4) |

4.8 (−0.4,10.1) |

1.8 (−3.1,6.7) |

1.4 (−1.0,3.8) |

0.7 (−3.9,5.3) |

| Having children | −1.7 (−6.1,2.7) |

−3.1 (−8.7,2.5) |

−4.8 (−10.6,0.9) |

−5.5**

(−9.5,−1.5) |

−1.3 (−6.5,4.0) |

| Cultural characteristics | |||||

| Urban area | −1.1 (−4.7,2.4) |

−0.6 (−5.0,3.7) |

0.9 (−3.2,5.0) |

1.0 (−1.2,3.2) |

0.1 (−3.7,3.9) |

| Linguistic region | |||||

| German-speaking (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| French-speaking | −4.4 (−8.8,0.0) |

−17.5***

(−22.9,−12.2) |

−7.2**

(−11.9,−2.5) |

−1.2 (−3.8,1.5) |

−6.8**

(−11.0,−2.5) |

| Italian-speaking | −17.2**

(−30.3,−4.2) |

−15.9*

(−29.0,−2.9) |

−6.2 (−16.7,4.3) |

−3.1 (−7.3,1.0) |

−4.2 (−14.1,5.6) |

| Practice of prayer | −14.1***

(−17.3,−10.9) |

−17.8***

(−22.1,−13.5) |

−15.6***

(−20.3,−11.0) |

−4.1**

(−6.8,−1.5) |

−12.7***

(−17.2,−8.2) |

| Experiential characteristics | |||||

| Self-rated health: (very) good/excellent | 1.1 (−3.5,5.6) |

2.4 (−3.2,8.0) |

−2.3 (−7.7,3.2) |

−1.6 (−4.6,1.4) |

−0.5 (−5.6,4.6) |

| 1+ limitations in activities of daily living | −1.0 (−7.8,5.7) |

−0.1 (−8.6,8.4) |

8.6 (−0.7,17.9) |

1.8 (−2.8,6.3) |

10.0*

(0.5,19.4) |

| Participation in making medical decisions for relative/friend | 5.5**

(1.6,9.5) |

4.4 (−0.8,9.6) |

7.5**

(2.4,12.6) |

4.6**

(1.3,7.8) |

4.9*

(0.1,9.7) |

| n (imputed data) | 2168 | 2168 | 2168 | 2168 | 2157 |

Average partial effects based on logistic regression models. All probabilities are multiplied by 100. Asterisks indicate levels of significance: *** <0.1%, ** 1%, * 5% Interpretation of APEs: having a high education level increases the probability of supporting the legality of assisted suicide, as is the case in Switzerland, by 12.7 percentage points compared to having a low education level. † Only respondents who were not members of a right-to-die organisation at the time of the survey answered this question.

We also find a positive monotonic association between education and assisted suicide attitudes and behaviour: the higher the education level of a respondent, the more favourable was their attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide. Thus, compared to respondents with low education levels, respondents with medium and high education levels were more likely to support the legality of assisted suicide (APE medium education: 6.4, p <5%; APE high education: 12.7, p <0.1%), more likely to potentially consider using assisted suicide under certain circumstances (APE medium education: 9.6, p <1%; APE high education: 17.2, p <0.1%), and more likely to already be (APE medium education: 4.3, p <0.1%; APE high education: 6.8, p <0.1%) or to plan to become (APE medium education: 10.9, p <0.1%; APE high education: 17.3, p <0.1%) a member of a right-to-die organisation. Furthermore, having children was negatively associated with the presence of favourable attitudes (not statistically significant) and the corresponding behaviour (APE: −5.5, p <1%) towards assisted suicide.

French-speaking and Italian-speaking respondents were less likely to show favourable attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide than German-speaking respondents, although these associations were not always statistically significant. Compared to respondents from the German-speaking regions of Switzerland, Italian-speaking respondents were less likely to support assisted suicide (APE: −17.2, p <1%) or to consider potentially using assisted suicide in the future (APE: −15.9, p <5%), while French-speaking respondents were also less likely to consider potentially using assisted suicide under certain circumstances (APE: −17.5, p <0.1%). In addition, French-speaking respondents were less likely to already be or to plan to become a member of a right-to-die organisation (APE: −7.2, p <1%) compared to German-speaking respondents.

The signs of the estimated associations of health status with assisted suicide-related attitudes and behaviour are different across our outcomes of interest, but the associations are generally not statistically significantly different from zero. However, having experience as a healthcare proxy was associated with positive attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide. Persons who had previous experience as a healthcare proxy were more likely to support assisted suicide (APE: 5.5, p <1%) and more likely to already be (APE: 4.6, p <1%) or plan to become a member of a right-to-die organisation (APE: 7.5, p <1%). Finally, people who practiced prayer were significantly less likely to support assisted suicide (APE: −14.1, p <0.1%), to potentially use assisted suicide (APE: −17.8, p <0.1%) and to already be (APE: −4.1, p <1%) or to plan to become a member of a right-to-die organisation (APE: −15.6, p <0.1%).

Table S2 in appendix 1 summarises the complete cases analysis.

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to assess general and personal approval of assisted suicide in Switzerland among a nationally representative sample of adults aged 55 and over since the Swiss government reaffirmed the status quo concerning the regulation of assisted suicide in 2011. In addition, our study offers detailed insights into how assisted suicide attitudes and behaviour vary according to individuals’ sociodemographic, cultural and experiential characteristics.

Our study shows high rates of support for assisted suicide (81.7%) and of potential use of assisted suicide for oneself (60.9%) among older adults in Switzerland. Several studies based on data from the European Values Study (EVS) and its sister studies have shown strong national variations in euthanasia acceptance, ranging from 1.44 to 6.81 on a ten-point scale (with ten indicating maximal acceptance) [24, 33–36]. In a review of studies on the acceptance of euthanasia, physician- and non-physician-assisted suicide in different population groups (ill and healthy people), Hendry et al. showed that two thirds of participants felt that euthanasia or assisted suicide was acceptable [37]. Our findings are not directly comparable with the results of those studies for several reasons. First, the large majority of these studies asked about the practice of euthanasia and/or physician-assisted suicide, and seldom about non-physician-assisted suicide, which is the current practice in Switzerland. Second, the reviewed practices were not necessarily legal in the considered study settings, which again is in contrast to the case for our study. Third, the samples of some of the studies included in the review involved patients with advanced medical conditions. Restricting our comparison to the Netherlands, i.e. a country where euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are legal, the level of favourable attitudes towards euthanasia in specific patient groups is close to our findings for assisted suicide in general: 85% of the general population in the Netherlands were reported to accept euthanasia requested by an incurable cancer patient with severe pain [38]. Also similar to our findings, 63% of Dutch persons aged 64 and over stated that they would potentially consider euthanasia for themselves [39].

We found that favourable attitudes towards assisted suicide were higher among respondents with higher education levels. While a majority of studies on the acceptance [24, 34–37] and potential use [39] of euthanasia or assisted suicide report a positive relationship with education level, some studies have found no association of education with support for euthanasia or assisted suicide attitudes [4, 40], and some have even found negative education gradients in support for euthanasia or assisted suicide attitudes [41, 42]. Education likely contributes to the development of personal values such as autonomy and personal freedom [43, 44], and may have an empowering effect that increases the capacity for emancipation and self-determination. Based on Belgian data, Chambaere et al. observed that patients with higher education levels were more likely to withhold or withdraw from different EOL treatments but were also more likely to receive drugs for pain management. These results suggest that individuals with higher education levels may be more concerned with self-determination and control of their EOL decisions, as well as more actively involved in their own treatment decisions [45]. Another study showed that individuals who report preferences for control over their EOL decisions and concerns regarding EOL-related mental and physical impairments are more likely to approve assisted suicide [46]. Reasons why individuals with higher education levels are more likely to support assisted suicide may include that assisted suicide can help them to achieve self-determination in death and to limit potentially unwelcome overtreatment and suffering at the end of life.

Lower importance of autonomy and self-determination in death for earlier generations may explain why older adults (75+) were less likely to support assisted suicide than their younger counterparts in our study. Individuals born before World War II grew up in a more hierarchical, religious and traditional societal context, where individualistic values were less prevalent [47]. These generations may, therefore, be less concerned about controlling their EOL decisions than individuals from the post-World War II generation, who were exposed to more progressive ideas in the context of an increasingly secular society [47]. Although the literature seems to provide only mixed evidence on patterns in the association of age with acceptance of any active ending of life, lower levels of support for such practices among older age groups have been observed in other cross-sectional studies, and are typically interpreted as due to cohort effects along the lines of those described above [34, 35, 39, 47, 48]. These explanations seem to be further supported by a cohort analysis of individuals aged 45 to 85 who were interviewed ten times over a 15-year period, which showed that chronological age does not appear to be a determinant of attitudes towards euthanasia, with non-decreasing levels of support as people aged [49].

While attitudes towards assisted suicide show strong cohort effects in our study, assisted suicide-related behaviour reveals age effects, with an increased likelihood of becoming a member of a right-to-die organisation with older age. This result shows that older individuals (75+) in favour of assisted suicide are more likely to take action and join a right-to-die organisation than less old adults (55–64), who may believe that they still have time to make that commitment.

In our study, previous participation in medical decision-making for relatives or friends was positively associated with both favourable attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide. Existing evidence regarding the associations of such experiences with views on euthanasia or assisted suicide is rather mixed, with some studies finding positive [37], no [50] or negative [42] associations between personal experiences with terminal illness of a relative or friend and/or being a family caregiver on the one hand and attitudes towards euthanasia or assisted suicide on the other. These diverging results may be attributable to heterogeneity in experiences as a healthcare proxy, including different levels of intensity of involvement in caring for and different types of illnesses of loved ones. In addition, different levels of closeness with the patient, differences in the quality of healthcare received and differences in the interactions with healthcare providers may explain the conflicting findings in the literature. Respondents’ own health status, by contrast, did not show any systematic associations with attitudes or behaviour towards assisted suicide in our study. A study on attitudes towards EOL decisions in the Dutch general public also reported no association between poor self-rated health and euthanasia acceptance [38], whereas some other studies have found a positive association of poor self-rated health with assisted suicide acceptance [41] and potential use of euthanasia [48].

Our results show that older adults from Italian- and French-speaking Switzerland have more negative attitudes towards assisted suicide compared to those from German-speaking Switzerland. Significant differences in EOL healthcare utilisation [51], medical EOL practices [52] and place of death [53] across the three linguistic regions of Switzerland are well documented. Interestingly, these regional differences often correspond with the differences observed between Switzerland’s neighbouring countries (Germany, Austria, France and Italy), which display patterns comparable to those of the Swiss regions with the same language and similar cultural characteristics. However, with regard to euthanasia acceptance, Italy (4.53), Austria (4.51) and Germany (4.69) have been found to have comparable mean scores to Switzerland (5.05), with only France (6.75) showing a higher score, where zero indicates that euthanasia is never justified and ten that euthanasia is always justified [35]. In Belgium, another country with distinct linguistic communities where different languages also partly reflect differences in culture, Cohen et al. observed no major differences in euthanasia acceptance between Flanders and Wallonia among the general public [54]. These authors did, however, report important differences in attitudes towards and the practice of euthanasia among Flemish and Walloon physicians, with cultural factors seeming to play an important role. More specifically, compared to Flemish physicians, Walloon physicians were more likely to declare that a physician’s duty is always to preserve life and were less likely to agree that euthanasia can form part of good EOL care. Comparing deaths at home or in care homes between the Flemish- and the Walloon-speaking communities, van den Block et al. found a higher prevalence of potentially life-shortening EOL decisions and a lower prevalence of continuous deep sedation in the Flemish-speaking community [55]. According to the authors, similar differences can also be found in the medical cultures of Southern and Northern Europe. Comparable differences have also been observed in Switzerland, with French-speaking physicians being more reluctant to withhold or withdraw certain treatments from patients than German-speaking physicians [56]. These studies highlight differences in medical attitudes and practices regarding EOL decisions between physicians from different linguistic regions of the same country. These regional differences cannot be explained by structural differences, since these regions are part of the same country, are governed by a single legal healthcare system and have common guidelines regarding EOL practice. Therefore, they are probably cultural differences that may well reflect the attitudes of the people living in these regions towards EOL decisions.

Practice of prayer was negatively associated with all five of our outcomes measuring older adults’ approval of assisted suicide. Most studies considering the relationship between religiosity and euthanasia or assisted suicide have found a negative association between these two characteristics [24, 34–41, 50, 57, 58]. In several religions, life is sacred and human beings are not allowed to decide the time of their death. As a consequence, individuals who believe and follow the teachings of such religions should be more likely to refuse euthanasia or assisted suicide, which is consistent with our data.

The sociodemographic characteristics that were associated with membership of a right-to-die organisation in our study (being female, 65+, having higher education, no children and non-practice of prayer) also characterise the members of EXIT A.D.M.D, one of the main right-to-die organisations in Switzerland [59]. Furthermore, individuals who died through assisted suicide in Switzerland between 2003 and 2008 were more likely to be female, to live alone, to have secondary or tertiary education, and to have no religious affiliation [12]. Although there is no direct link between being a member of a right-to-die organisation and seeking assisted suicide, people who agree with the practice of assisted suicide share similar characteristics with people who are registered with a right-to-die organisation or who died by assisted suicide. This consistency of associations across assisted suicide-related outcomes strongly suggests that our measures of assisted suicide-related attitudes and behaviour do indeed map onto actual assisted suicide-related behaviours outside of the context of our survey.

Our study suffers from several limitations. First, although borderline cases of assisted suicide are widely publicised in local media, it is likely that not all individuals in Switzerland understand the exact regulation of assisted suicide and its differences from other countries where euthanasia and/or assisted suicide is legal. Thus, our study may not help to answer the question of whether or not the general population is satisfied with the current legal framework (or lack thereof) for assisted suicide in Switzerland, but rather might just show that the relatively “open” assisted suicide regulation that is currently in place is not a barrier to wide support for the practice of assisted suicide in Switzerland. Second, we measured attitudes and behaviour towards the practice of non-physician-assisted suicide, which is not directly comparable with the practice of euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide, which are what most other studies on public support for common assisted dying practices have investigated. However, several studies do not explicitly differentiate between the different practices of assisted suicide and/or euthanasia, as they often use a generic terminology such as “voluntary active ending of life”. As a result, our results may provide interesting insights beyond the Swiss context, even if assisted suicide practice in Switzerland is not directly comparable to the corresponding practices in other countries. Third, while attitudes often predict behaviour [60], the link between attitudes and behaviour may be less strong when asking healthy individuals to assess their likely future behaviour in the hypothetical situation of serious illness. However, some studies show that the link between attitudes and behaviour may be reliable even in the context of hypothetical EOL planning, as individuals’ values relating to death and dying appear to be stable over time [39]. Moreover, most people who die by assisted suicide have already made the decision to consider assisted suicide prior to their illness [14]. Thus, we consider our results likely to be predictive of a higher use of assisted suicide in specific population groups under certain circumstances.

The principles of autonomy and self-determination are generally highly valued by the Swiss population [61], and this importance of autonomy and self-determination is also reflected in the overall favourable attitudes towards assisted suicide among older adults observed in our study. However, assisted suicide-related attitudes and behaviour vary significantly with the individuals’ sociodemographic and cultural characteristics, as well as with their previous experiences. In particular, population groups which could be considered more vulnerable to the misuse or outright abuse of euthanasia and assisted suicide, such as individuals with low levels of education or older adults (75+), overall viewed the current practice of assisted suicide in Switzerland less favourably. Fears that more vulnerable population groups may be at greater risk of seeking assisted suicide do not, therefore, seem to be corroborated in Switzerland. A similar pattern was observed in an epidemiological study which showed that the actual use of assisted suicide in Switzerland is higher among persons with higher education levels, with Swiss nationality, and who live in neighbourhoods with a higher socioeconomic index [11]. Moreover, we found different cultural sensitivities towards assisted suicide across the three linguistic regions of Switzerland. These are likely to reflect different attitudes and approaches to death, which should be further investigated in future research. Finally, personal experience with death and dying, such as making EOL decisions for a loved one, also appears to make older adults view the practice of assisted suicide more favourably.

While the approval of assisted suicide is generally high in Switzerland, certain population groups appear to be more sceptical about the practice of assisted suicide. Our data suggest that differences in values (autonomy, self-determination), beliefs (religion) and culture may be important drivers of individuals’ views of assisted suicide, even if other factors almost certainly also play a role. Some individuals might be opposed to assisted suicide because of the lack of regulation of the practice in Switzerland. Conversely, lack of knowledge about EOL issues and the available EOL care and planning options may lead individuals to view assisted suicide as a relatively straightforward solution to the complex issues and planning requirements presented by EOL care and dying. The risk that individuals see assisted suicide as a simple solution to the more complex challenges of EOL is real for two reasons. First, assisted suicide is widely reported in the Swiss media, whereas information about palliative care, advance directives and other forms of EOL planning is discussed less often. Second, there are significant knowledge gaps among the population regarding different EOL options [62, 63]. Currently, only a small minority of individuals use assisted suicide. However, given the trend of increasing use of assisted suicide over the last few years, it is imperative that individuals are properly informed about the full range of available EOL options to ensure that every citizen can make informed decisions about EOL choices.

Table S1 Distribution of missing values in the sample, adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, SHARE 2015 (n = 2549).

| Rate of missing values (%) | |

|---|---|

| Sex | 0 |

| Age | 0 |

| Education level | 1.41 |

| Partner living in household | 0.35 |

| Having children | 0.12 |

| Self-rated health | 0.08 |

| Limitations in activities of daily living | 0 |

| Practice of prayer | 6.12 |

| Healthcare proxy experience | 5.14 |

| Urban vs rural area | 1.26 |

| Linguistic region | 0 |

| Support the legality of assisted suicide as is currently the case in Switzerland | 6.36 |

| Could consider asking for assisted suicide | 6.20 |

| Is a member or likely to become a member of a right-to-die organisation | 7.38 |

| Is a member of a right-to-die organisation | 4.16 |

Table S2 Complete cases analysis. Average partial effects (APEs) based on logistic regressions of attitudes and behaviour towards assisted suicide by sociodemographic and family characteristics, self-rated health status, practice of prayer, experience as a healthcare proxy and geographical location in adults aged 55+ in Switzerland, SHARE 2015.

| Support the legality of assisted suicide as is the case in Switzerland | Could consider asking for assisted suicide | Is a member or likely to become a member of a right-to-die organisation | Is a member of a right-to-die organisation | Is likely to become a member of a right-to-die organisation† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | APE (95% CI) | |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |||||

| Women | 1.4 (−1.6,4.5) |

−1.7 (−5.8,2.3) |

3.7 (−0.0,7.5) |

2.4**

(0.6,4.2) |

2.2 (−1.6,6.0) |

| Age groups | |||||

| 55–64 (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| 65–74 | 4.5*

(0.5,8.5) |

0.3 (−4.8,5.3) |

4.5 (−0.1,9.2) |

2.2*

(0.1,4.4) |

3.0 (−1.7,7.6) |

| 75+ | −4.1 (−9.0,0.8) |

−7.4*

(−13.2,−1.5) |

−3.1 (−8.4,2.3) |

6.1***

(2.8,9.4) |

−7.7**

(−12.8,−2.6) |

| Education level | |||||

| Low education (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| Medium education | 6.0*

(0.5,11.6) |

9.6**

(2.9,16.3) |

10.1***

(4.5,15.6) |

4.3***

(2.5,6.2) |

6.6*

(1.0,12.1) |

| High education | 12.5***

(6.1,18.9) |

16.3***

(8.4,24.3) |

16.5***

(9.2,23.7) |

7.3***

(3.8,10.8) |

11.3**

(4.1,18.5) |

| Partner living in household | 0.2 (−3.9,4.3) |

3.8 (−1.5,9.2) |

1.8 (−3.3,7.0) |

1.2 (−1.3,3.7) |

0.6 (−4.4,5.7) |

| Having children | −1.1 (−5.7,3.5) |

−2.5 (−8.3,3.4) |

−4.8 (−10.7,1.1) |

−6.1**

(−10.2,−1.9) |

−0.5 (−6.0,5.0) |

| Cultural characteristics | |||||

| Urban area | −1.6 (−5.2,2.1) |

−0.9 (−5.3,3.5) |

1.1 (−3.1,5.3) |

0.6 (−1.7,2.9) |

0.6 (−3.5,4.7) |

| Linguistic region | |||||

| German-speaking (ref.) | – | – | – | – | – |

| French-speaking | −4.8*

(−9.4,−0.1) |

−17.3***

(−22.8,−11.7) |

−7.4**

(−12.3,−2.5) |

−0.8 (−3.5,2.0) |

−7.3**

(−11.9,−2.7) |

| Italian-speaking | −17.8*

(−32.0,−3.6) |

−17.9*

(−31.7,−4.1) |

−7.9 (−18.3,2.5) |

−2.6 (−7.2,2.1) |

−6.4 (−16.5,3.7) |

| Practice of prayer | −14.9***

(−18.0,−11.7) |

−19.0***

(−23.3,−14.7) |

−16.5***

(−21.3,−11.8) |

−4.5***

(−7.1,−1.8) |

−14.1***

(−18.8,−9.3) |

| Experiential characteristics | |||||

| Self-rated health: (very) good/excellent | 1.1 (−3.6,5.8) |

3.4 (−2.5,9.2) |

−1.4 (−7.0,4.2) |

−1.5 (−4.4,1.5) |

−0.6 (−6.1,5.0) |

| 1+ limitations in the activities of daily living | −1.7 (−8.7,5.3) |

−0.5 (−9.4,8.4) |

9.5 (−0.3,19.3) |

2.8 (−2.3,7.9) |

7.6 (−2.5,17.7) |

| Participation in making medical decisions for relative/friend | 5.1*

(1.1,9.2) |

3.8 (−1.6,9.1) |

6.6*

(1.5,11.8) |

4.2*

(0.9,7.5) |

4.0 (−1.1,9.1) |

| n (listwise deletion) | 2030 | 2030 | 2030 | 2030 | 1918 |

Average marginal effects based on logistic regression models. All probabilities are multiplied by 100. Asterisks indicate levels of significance: *** <0.1%, ** 1%, * 5%. † Only respondents who were not members of a right-to-die organisation at the time of the survey answered this question.

The authors are grateful to Prof. André Berchtold for his support and useful advice in conducting and reporting the data imputations. They also warmly thank Sylvia Goetze Wake for her support in the process of writing the paper in English.

This paper uses data from SHARE Wave 6 (DOI:10.6103/SHARE.w6.700), see Börsch-Supan et al. (2013) for methodological details.

The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SERISS: GA N°654221), and by the DG for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), the Swiss National Sciences Foundation and various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

1 Materstvedt LJ , Clark D , Ellershaw J , Førde R , Gravgaard AM , Müller-Busch HC , et al.; EAPC Ethics Task Force. Euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a view from an EAPC Ethics Task Force. Palliat Med. 2003;17(2):97–101, discussion 102–79. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1191/0269216303pm673oa

2 Andorno R . Nonphysician-assisted suicide in Switzerland. Camb Q Healthc Ethics. 2013;22(3):246–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180113000054

3 Steck N , Egger M , Maessen M , Reisch T , Zwahlen M . Euthanasia and assisted suicide in selected European countries and US states: systematic literature review. Med Care. 2013;51(10):938–44. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e3182a0f427

4Schwarzenegger C, Manzoni P, Studer D, Leanza C. Was die Schweizer Bevölkerung von Sterbehilfe und Suizidbeihilfe hält. Jusletter. 2010.

5FSO. Suicide assisté selon le sexe et l'âge. T14.03.04.01.14 ed. Neuchâtel: Federal Statistical Office; 2016.

6 Bosshard G , Fischer S , Bär W . Open regulation and practice in assisted dying. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132(37-38):527–34.

7Le Conseil fédéral. Soins palliatifs, prévention du suicide et assistance organisée au suicide. Berne: Conférdération suisse. 2011.

8 Borasio GD . Suizidhilfe aus ärztlicher Sicht – die vernachlässigte Fürsorge. Schweiz Arzteztg. 2015;96(24):889–91. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/saez.2015.03545

9 Borasio GD , Jox RJ , Gamondi C . Regulation of assisted suicide limits the number of assisted deaths. Lancet. 2019;393(10175):982–3. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32554-6

10 Steck N , Zwahlen M , Egger M ; Swiss National Cohort. Time-trends in assisted and unassisted suicides completed with different methods: Swiss National Cohort. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14153. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14153

11 Steck N , Junker C , Zwahlen M ; Swiss National Cohort. Increase in assisted suicide in Switzerland: did the socioeconomic predictors change? Results from the Swiss National Cohort. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4):e020992. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020992

12 Steck N , Junker C , Maessen M , Reisch T , Zwahlen M , Egger M ; Swiss National Cohort. Suicide assisted by right-to-die associations: a population based cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):614–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu010

13 Steck N , Egger M , Zwahlen M ; Swiss National Cohort. Assisted and unassisted suicide in men and women: longitudinal study of the Swiss population. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;208(5):484–90. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160416

14 Gamondi C , Pott M , Payne S . Families’ experiences with patients who died after assisted suicide: a retrospective interview study in southern Switzerland. Ann Oncol. 2013;24(6):1639–44. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdt033

15 Fischer S , Huber CA , Furter M , Imhof L , Mahrer Imhof R , Schwarzenegger C , et al. Reasons why people in Switzerland seek assisted suicide: the view of patients and physicians. Swiss Med Wkly. 2009;139(23-24):333–8.

16GfK. Résumé des résultats de l'étude «Soins palliatifs». Berne: GfK Switzerland SA; 2009.

17Brügger B, Lalive R, Zweimüller J. Does Culture Affect Unemployment? Evidence from the Röstigraben. CESifo Working Paper Series. 2009;2714

18 Gire J . How death imitates life: Cultural influences on conceptions of death and dying. Online Read Psychol Cult. 2014;6(2). doi:.https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1120

19 Martín JM , Olano-Lizarraga M , Saracíbar-Razquin M . The experience of family caregivers caring for a terminal patient at home: A research review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;64:1–12. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.09.010

20 Wendler D , Rid A . Systematic review: the effect on surrogates of making treatment decisions for others. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(5):336–46. doi:.https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-154-5-201103010-00008

21 van Wijmen MP , Pasman HR , Widdershoven GA , Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD . Motivations, aims and communication around advance directives: a mixed-methods study into the perspective of their owners and the influence of a current illness. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;95(3):393–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2014.03.009

22 Benatar D . A legal right to die: responding to slippery slope and abuse arguments. Curr Oncol. 2011;18(5):206–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3747/co.v18i5.923

23 Givens JL , Mitchell SL . Concerns about end-of-life care and support for euthanasia. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):167–73. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2008.08.012

24 Verbakel E , Jaspers E . A Comparative Study on Permissiveness Toward Euthanasia: Religiosity, Slippery Slope, Autonomy, and Death with Dignity. Public Opin Q. 2010;74(1):109–39. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfp074

25 Emanuel EJ , Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD , Urwin JW , Cohen J . Attitudes and Practices of Euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide in the United States, Canada, and Europe. JAMA. 2016;316(1):79–90. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.8499

26Börsch-Supan A. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) Wave 6. Release version: 6.1.1. In: SHARE-ERIC, editor.2018.

27SHARE. End-of-life questionnaire. Munich: Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy (MEA); 2015 [cited 2018 April 14]; Available from: http://www.share-project.org/fileadmin/pdf_questionnaire_wave_6/DO_EN_SHARE_04.12.2014corr.pdf.

28UNESCO. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 1997. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2006.

29Egli S, Mayer B, Mast F, eds. Cultural differences and similarities among German-, French- and Italian speaking Switzerland and neighboring countries. 15th Swiss Psychological Society Conference; 2017; Lausanne.

30 Laesser C , Beritelli P , Heer S . Different native languages as proxy for cultural differences in travel behaviour: insights from multilingual Switzerland. Int J Cult Tour Hosp Res. 2014;8(2):140–52. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-02-2014-0010

31 Little RJA . A Test of Missing Completely at Random for Multivariate Data with Missing Values. J Am Stat Assoc. 1988;83(404):1198–202. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722

32Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987.

33 Cohen J , Van Landeghem P , Carpentier N , Deliens L . Different trends in euthanasia acceptance across Europe. A study of 13 western and 10 central and eastern European countries, 1981-2008. Eur J Public Health. 2013;23(3):378–80. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cks186

34 Cohen J , Marcoux I , Bilsen J , Deboosere P , van der Wal G , Deliens L . European public acceptance of euthanasia: socio-demographic and cultural factors associated with the acceptance of euthanasia in 33 European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(3):743–56. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.01.026

35 Cohen J , Van Landeghem P , Carpentier N , Deliens L . Public acceptance of euthanasia in Europe: a survey study in 47 countries. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(1):143–56. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-013-0461-6

36 Köneke V . Trust increases euthanasia acceptance: a multilevel analysis using the European Values Study. BMC Med Ethics. 2014;15(1):86. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-15-86

37 Hendry M , Pasterfield D , Lewis R , Carter B , Hodgson D , Wilkinson C . Why do we want the right to die? A systematic review of the international literature on the views of patients, carers and the public on assisted dying. Palliat Med. 2013;27(1):13–26. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216312463623

38 Rietjens JA , van der Heide A , Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD , van der Maas PJ , van der Wal G . A comparison of attitudes towards end-of-life decisions: survey among the Dutch general public and physicians. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(8):1723–32. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.03.024

39 Buiting HM , Deeg DJ , Knol DL , Ziegelmann JP , Pasman HR , Widdershoven GA , et al. Older peoples’ attitudes towards euthanasia and an end-of-life pill in The Netherlands: 2001-2009. J Med Ethics. 2012;38(5):267–73. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2011-100066

40 O’Neill C , Feenan D , Hughes C , McAlister DA . Physician and family assisted suicide: results from a study of public attitudes in Britain. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(4):721–31. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00421-5

41 Stolz E , Mayerl H , Gasser-Steiner P , Freidl W . Attitudes towards assisted suicide and euthanasia among care-dependent older adults (50+) in Austria: the role of socio-demographics, religiosity, physical illness, psychological distress, and social isolation. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):71. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0233-6

42 Stronegger WJ , Burkert NT , Grossschädl F , Freidl W . Factors associated with the rejection of active euthanasia: a survey among the general public in Austria. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14(1):26. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-14-26

43 Van Hiel A , Van Assche J , De Cremer D , Onraet E , Bostyn D , Haesevoets T , et al. Can education change the world? Education amplifies differences in liberalization values and innovation between developed and developing countries. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199560. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199560

44 Caddell DP , Newton RR . Euthanasia: American attitudes toward the physician’s role. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40(12):1671–81. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(94)00287-4

45 Chambaere K , Rietjens JA , Cohen J , Pardon K , Deschepper R , Pasman HR , et al. Is educational attainment related to end-of-life decision-making? A large post-mortem survey in Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):1055. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1055

46 Vilpert S , Borrat-Besson C , Borasio GD , Maurer J . Associations of end-of-life preferences and trust in institutions with public support for assisted suicide evidence from nationally representative survey data of older adults in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232109. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232109

47 Poli S . Attitudes Toward Active Voluntary Euthanasia Among Community-Dwelling Older Subjects. SAGE Open. 2018;8(1). doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017753868

48 Scherrens AL , Roelands M , Van den Block L , Deforche B , Deliens L , Cohen J . What influences intentions to request physician-assisted euthanasia or continuous deep sedation? Death Stud. 2018;42(8):491–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1386734

49 Leinbach RM . Euthanasia Attitudes of Older Persons - a Cohort Analysis. Res Aging. 1993;15(4):433–48. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027593154004

50 Braun KL , Tanji VM , Heck R . Support for physician-assisted suicide: exploring the impact of ethnicity and attitudes toward planning for death. Gerontologist. 2001;41(1):51–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/41.1.51

51 Reich O , Signorell A , Busato A . Place of death and health care utilization for people in the last 6 months of life in Switzerland: a retrospective analysis using administrative data. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):116. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-116

52 Hurst SA , Zellweger U , Bosshard G , Bopp M ; Swiss Medical End-of-Life Decisions Study Group. Medical end-of-life practices in Swiss cultural regions: a death certificate study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1043-5

53 Panczak R , Luta X , Maessen M , Stuck AE , Berlin C , Schmidlin K , et al. Regional Variation of Cost of Care in the Last 12 Months of Life in Switzerland: Small-area Analysis Using Insurance Claims Data. Med Care. 2017;55(2):155–63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000634

54 Cohen J , Van Wesemael Y , Smets T , Bilsen J , Deliens L . Cultural differences affecting euthanasia practice in Belgium: one law but different attitudes and practices in Flanders and Wallonia. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75(5):845–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.04.021

55 Van den Block L , Deschepper R , Bilsen J , Bossuyt N , Van Casteren V , Deliens L . Euthanasia and other end-of-life decisions: a mortality follow-back study in Belgium. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):79. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-79

56 Fischer S , Bosshard G , Faisst K , Tschopp A , Fischer J , Bär W , et al. Swiss doctors’ attitudes towards end-of-life decisions and their determinants: a comparison of three language regions. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(23-24):370–6.

57 Danyliv A , O’Neill C . Attitudes towards legalising physician provided euthanasia in Britain: the role of religion over time. Soc Sci Med. 2015;128:52–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.12.030

58 Lapierre S , Castelli Dransart DA , St-Amant K , Dubuc G , Houle M , Lacerte MM , et al. Religiosity and the Wish of Older Adults for Physician-Assisted Suicide. Religions (Basel). 2018;9(3):66. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9030066

59 Pott M , Cavalli S , Stauffer L , Lou Beltrami S . Les membres âgés des ADMD: des personnes déterminées et un défi à relever pour les soignants. Angewandte Gérontologie Appliquée. 2018;3:23–6.

60 Sheeran P , Webb TL . The Intention-Behavior Gap. Soc Personal Psychol Compass. 2016;10(9):503–18. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12265

61Abrams D, Vauclair CM, Swift H. Predictors of attitudes to age across Europe. Research report no. 375. Sheffield: Department for Work and Pensions; 2011.

62 Vilpert S , Borrat-Besson C , Maurer J , Borasio GD . Awareness, approval and completion of advance directives in older adults in Switzerland. Swiss Med Wkly. 2018;148:w14642. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14642

63 Vilpert S , Maurer J , Borasio GD . Knowledge gaps with regard to end-of-life care and planning options among older adults in Switzerland. Submitted manuscript. 2020.

The SHARE data collection has been funded by the European Commission through FP5 (QLK6-CT-2001-00360), FP6 (SHARE-I3: RII-CT-2006-062193, COMPARE: CIT5-CT-2005-028857, SHARELIFE: CIT4-CT-2006-028812), FP7 (SHARE-PREP: GA N°211909, SHARE-LEAP: GA N°227822, SHARE M4: GA N°261982) and Horizon 2020 (SHARE-DEV3: GA N°676536, SERISS: GA N°654221), and by the DG for Employment, Social Affairs & Inclusion. Additional funding from the German Ministry of Education and Research, the Max Planck Society for the Advancement of Science, the U.S. National Institute on Aging (U01_AG09740-13S2, P01_AG005842, P01_AG08291, P30_AG12815, R21_AG025169, Y1-AG-4553-01, IAG_BSR06-11, OGHA_04-064, HHSN271201300071C), the Swiss National Sciences Foundation and various national funding sources is gratefully acknowledged (see www.share-project.org).

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.