2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV): estimating the case fatality rate – a word of caution

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2020.20203

Manuel

Battegaya, Richard

Kuehla, Sarah

Tschudin-Suttera, Hans H.

Hirschabc, Andreas F.

Widmera, Richard A.

Neherd

aDivision of Infectious Diseases & Hospital Epidemiology, University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, Switzerland

bClinical Virology, Laboratory Medicine, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland

c Transplantation and Clinical Virology, Department Biomedicine, University of Basel, Switzerland

dBiozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland

Estimating and predicting the extent and lethality of the 2019-Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak, originating in Wuhan/China is obviously challenging, reflected by many controversial statements and reports. Unsurpassed to date, an ever-increasing flow of information, immediately available and accessible online, has allowed the description of this emerging epidemic in real-time [1]. The first patients were reported in Wuhan on December 31st 2019 [2]. Only a few days later, Chinese researchers identified the etiologic agent now known as the 2019-nCoV and published the viral sequence [3]. New data on the virus, its characteristics and epidemiology become available 24/7 and are often shared via informal platforms and media [4]. Yet, key questions remain largely unanswered.

How is the virus transmitted, how long is the incubation period, what is the role of asymptomatic infected, what is the definite reproductive number R0, how long is viral shedding persisting after fading of symptoms, who is at risk for a severe course, and ultimately, how high is the case fatality rate?

Accurate answers are critical for predicting the outbreak dynamics, to tailor appropriate and effective prevention measures, and to prepare for a potential pandemic. Precise estimates of the case fatality rate and the fraction of infections that require hospitalization are critical to balance the socioeconomic burden of infection control interventions against their potential benefit for mankind. Hence, one of the most important figures to determine is the rate of asymptomatic and mild cases allowing to put severe courses and death rates into accurate context.

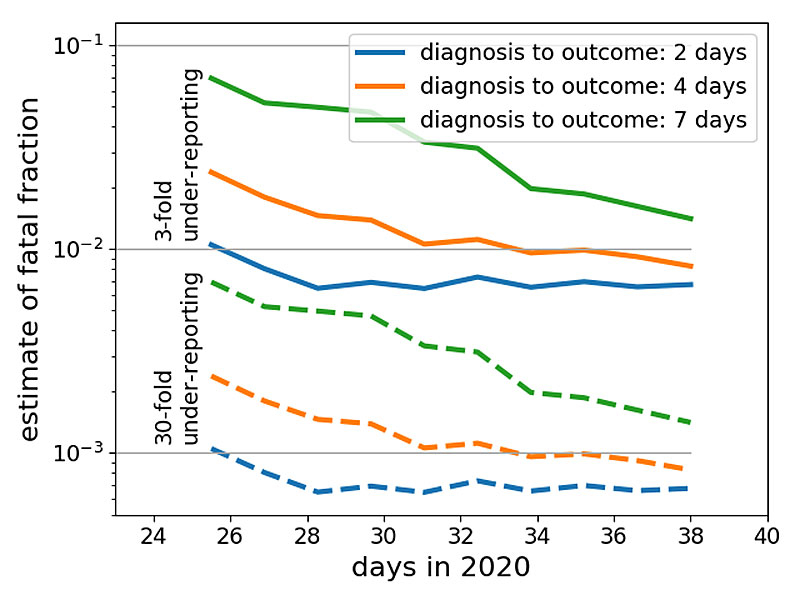

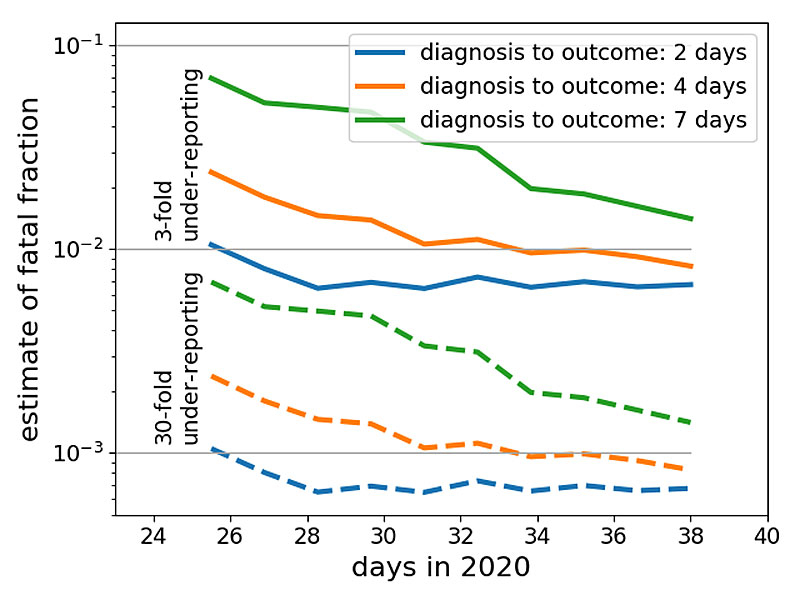

At present, it is tempting to estimate the case fatality rate by dividing the number of known deaths by the number of confirmed cases. The resulting number, however, does not represent the true case fatality rate and might be off by orders of magnitude. Diagnosis of viral infection will precede recovery or death by days to weeks and the number of deaths should therefore be compared to the past case counts – accounting for this delay increasing the estimate of the case fatality rate. On the other hand, cases in official statistics are likely a severe underestimate of the total – accounting for this underestimate will decrease the case fatality rate. The time between diagnosis and death/recovery and the degree of underreporting will vary over time as well as between cities and countries. A precise estimate of the case fatality rate is therefore impossible at present. Figure 1 illustrates how these uncertainties manifest themselves using currently available data.

Figure 1 Uncertainties of naive case count estimates. This graph shows how the ratio of the number of confirmed deaths and case counts changed over time. Case counts are corrected for 3-fold or 30-fold under-reporting (solid and dashed lines, respectively) and are taken 2, 4, and 7 days prior to the date of the count of confirmed death. The latter is meant to illustrate the effect of the delay between diagnosis and death or recovery. This actual delay is likely longer than one week. Data source: https://github.com/globalcitizen/2019-wuhan-coronavirus-data.

Better estimates could be derived from large-scale investigations, in particular, in the region of the epidemic’s origin. Still, population-based testing of respiratory secretions by nucleic acid amplification testing (NAT) for 2019-nCoV would most likely underestimate the scale of the outbreak, as asymptomatic patients or patients after recovery from infection may no longer be NAT-positive. A sensitive 2019-nCoV-specific serological assay is needed to firmly assess the rate of past exposure and may help to assess herd immunity.

One intriguing aspect of the outbreak so far is the discrepancy between the estimates of the case fatality rate reported from Hubei province, from different regions of China and from other countries. As of February 7, 2020, 30’536 have been confirmed. Thereof, 22’112 occurred in the Hubei province of China with a death toll of 619 (= 2.8%). This contrasts with 16 deaths among 8’702 recorded cases in other regions of China and further countries, suggesting at first glance a case fatality rate of 0.18%. The uncertainties and spatio-temporal variation discussed above could explain this divergence:

The higher case fatality rate reported from Wuhan may be overestimated

- The true number of exposed cases affected in Wuhan may be vastly underestimated. With a focus on thousands of serious cases, mild or asymptomatic courses that possibly account for the bulk of the 2019-nCoV infections might remain largely unrecognized, in particular during the influenza season.

- Under-detection of mild or asymptomatic cases may be further fueled after further growth of the outbreak, as healthcare-facilities and testing capacities in Wuhan have reached their limits.

Accordingly, the official numbers of both cases and deaths reported from Wuhan represent the “tip of the iceberg”, potentially skewing case fatality estimates towards patients presenting with more severe disease and fatal outcome. As the current measures in Wuhan aim at slowing the spread, other regions of China and countries gained critical time for preparations permitting to better track cases from the first occurrence of the virus in their populations. Thus, estimates deriving from these settings may be more accurate. That case fatality rates appear to decrease overall renders this hypothesis plausible.

The lower case fatality rates outside Wuhan may be underestimated

- As the epidemic arrived later in other regions and countries, there may be a delay of fatal cases arising and their reporting. The low number of documented recovered cases might indicate that days and weeks can pass until death occurs. Hence, the numbers, e.g. in Guangdong with 970 cases and no death occurring, might be false low because severe cases might still have a deadly outcome.

- Testing patients with severe respiratory diseases in outside of China might have been delayed so that unclear deaths are not yet being attributed to the coronavirus. This is unlikely at this point as international awareness has increased, but may have resulted in an underestimation of attributable deaths previously.

Case fatality rates may truly differ among different regions of the world

- Supportive care is crucial for severe respiratory disease. Differences in case fatality rates may be caused by differences in medical care during a large epidemic versus care for single cases. Hence, the large-scale capacities for medical care in the Hubei province, and specifically large-scale intensive care and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may lag behind the epidemic. This hypothesis is supported by the construction of two hospitals in record time.

- There are different susceptibilities to the 2019-Novel Coronavirus in different regions of China as well as different regions of the world. However, as this is the second coronavirus emerging from China, it is unlikely that herd-immunity is lower in this region of the world, than in others. Immunogenetics and socioeconomic factors however, may potentially contribute to differences in susceptibilities to the disease.

Current authorities such as the World Health Organization, the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (USA), the European Centers for Disease Control as well as renowned journals are challenged by the rapid generation and dissemination of data, largely published on social media platforms. Thus, new approaches will have to be defined to validate the accuracy of such posts in times where multiple tweets per second are published, sometimes with misleading, sometimes with important information. Modelling the 2019-nCoV epidemic remains challenging as relevant questions are still unanswered. So, despite the dramatic increase of rapidly available data, public health authorities remain torn back and forth between the options of overreacting and frightening the population or underreacting putting citizen at risk in their aim to provide advice to countries and individuals on measures to protect health and prevent the spread of this outbreak.

References

1

Li

Q

,

Guan

X

,

Wu

P

,

Wang

X

,

Zhou

L

,

Tong

Y

, et al.

Early Transmission Dynamics in Wuhan, China, of Novel Coronavirus-Infected Pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMoa2001316. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2001316

2Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet 2020.

3

Wu

F

,

Zhao

S

,

Yu

B

,

Chen

YM

,

Wang

W

,

Song

ZG

, et al.

A new coronavirus associated with human respiratory disease in China. Nature. 2020. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2008-3

4

Wu

JT

,

Leung

K

,

Leung

GM

. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020;S0140-6736(20)30260-9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9