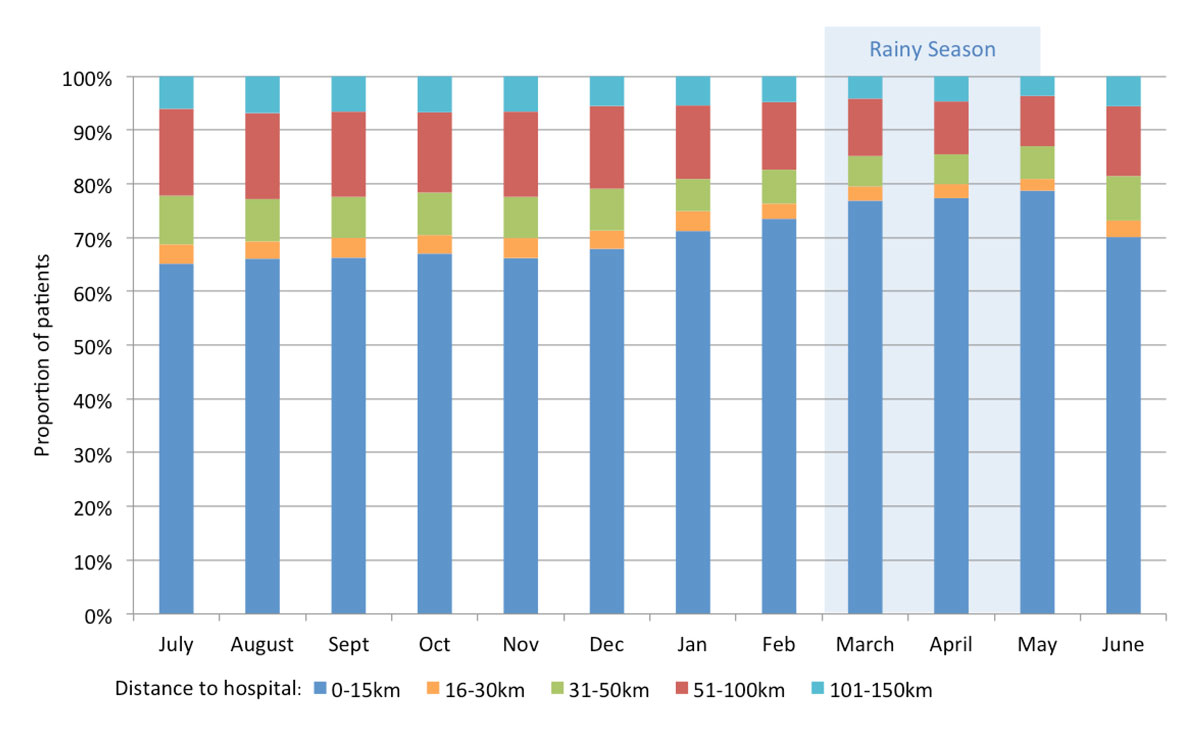

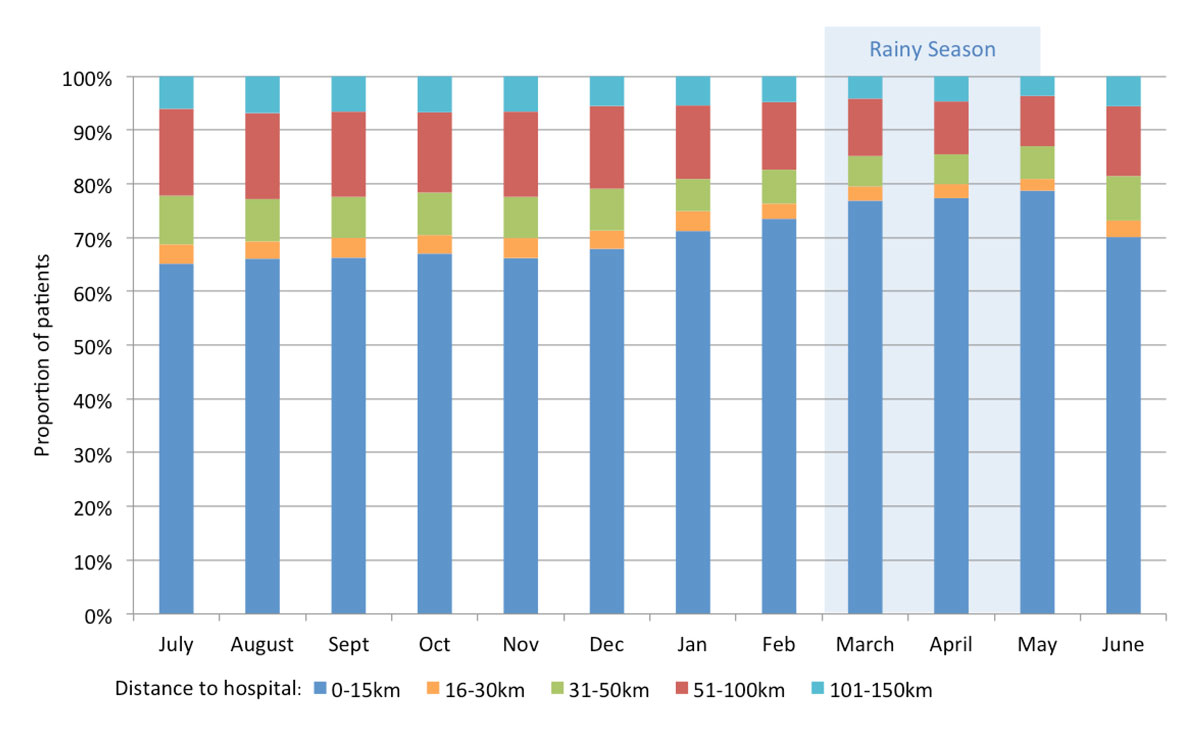

Figure 1 Distribution of patients according to distance home to hospital. Bars represent monthly proportions of emergency department patients with respect to distance from home to the hospital. The rainy season is marked in blue (March-May).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2019.20018

Emergency medical services are increasingly recognised as a critically important component of national health systems in low- and middle-income countries [1, 2]. Although large numbers of patients seek emergency care in health facilities, only few hospitals in low- and middle-income countries have an emergency department. Furthermore, these emergency departments often have limited functionality due to lack of formally trained staff, insufficient funding, inadequate infrastructure or equipment and limited supply of consumables [3, 4]. Information on diagnoses made in emergency departments of hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa is scarce, and there are no reports on hospital mortality rates before and after implementing an emergency department in a rural hospital. However, the implementation of a triaging system and training of clinical staff in emergency care has been shown to be associated with a decrease of in-hospital mortality rates in urban hospitals in Malawi, Sierra Leone and Tanzania [5–8]. During 1 year, we prospectively collated diagnoses of all patients presenting to the newly established emergency department in the St Francis Referral Hospital in Ifakara, Tanzania, and recorded in-hospital mortality rates before and after the implementation of the emergency department. Our aim was to evaluate the frequency of different diagnoses made in the emergency department, so that relevant healthcare requirements for our hospital could be defined. In addition, we wanted to find out if in-hospital mortality rates would decrease after implementing the emergency department.

This prospective observational study was performed in the St Francis Referral Hospital in Ifakara, Tanzania, which serves as a referral centre for about one million people living in rural Kilombero, Ulanga, and Malinyi districts. It has 360 beds and specialised services in internal medicine, surgery, obstetrics, urology, neonatology and gynaecology, ophthalmology, and paediatrics, has a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and tuberculosis clinic, but has no proper intensive care unit. Before the emergency department was available, all patients seeking care for an acute health problem were seen at the outpatient clinic by an intern doctor or a clinician on call. No triaging system or emergency care was available.

In September 2015, an emergency department was constructed and emergency services were implemented, including a triaging system, with a triple-shift operational service, and training in emergency medicine and ultrasound including emergency and abdominal sonography. Additionally, echocardiography by a formally trained and experienced physician was offered for patients with signs and symptoms of heart failure. For triage, the South African Triage Scale (SATS), a scoring system previously validated in resource-limited settings, was implemented [9–11] and applied to all patients presenting from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., i.e., during peak admission periods. During evening and night hours, triage was performed conventionally following the opinion of the responsible clinicians on duty.

The former outpatient clinic with its staff was incorporated into the new emergency department. Since January 2016, it runs with a triple-shift duty roster 24 hours a day. The medical staff comprises 13 nurses, 7 clinicians, and 5–6 intern doctors who rotate every 2 months. The emergency department is supported by an experienced emergency medicine physician. It has three consultation rooms available for emergency patients without serious conditions and an emergency room for patients with life-threatening conditions (i.e., patients with abnormal vital signs, respiratory failure, decreased consciousness, polytrauma, bleeding, or severe pain in need of immediate care). The emergency room is equipped with two monitors for noninvasive blood pressure measurement, oxygen saturation and electrocardiogram monitoring, and a permanently available ultrasound and electrocardiogram machine. Point-of-care tests available 24 hours a day include malaria rapid diagnostic test (SD Bioline Malaria Ag/P.f/Pan, Abbott, USA), urine pregnancy test strips (Occidem Biotec, UK), urine dipstick (Combur 10Test, Roche, Switzerland) and blood glucose tests (On Call Plus, ACON, USA). Additionally, radiography and laboratory tests such as complete blood count with differential, liver and kidney function tests, urine analysis, Xpert MTB/RIF, HIV testing (SD Bioline HIV 1/2 3.0, Abbott, USA, and Uni-Gold HIV Rapid Test, Trinity Biotech, USA) and hepatitis serology are available. For emergency treatment, noninvasive airway management tools, oxygen, emergency drugs, fluids and a defibrillator are available.

Diagnoses are made clinically by the clinician on duty and with the help of above-mentioned available tests, if indicated. Documentation is done by the responsible clinician in the patient’s medical booklet, if available, and additionally for all patients on a standardised patient log form on paper, for hospital statistics. After every shift, this document is collected by the data team from every clinician and stored and locked in a secured data room.

All patients who visited the emergency department from July 2016 to June 2017 were eligible. Patients from neonatal and labour wards were not included, because these patients are not seen at the emergency department.

The study was approved by the ethics committee in Switzerland (Ethikkomission Nordwest und Zentralschweiz (EKNZ UBE-15/83)) and the ethics committees of the Ifakara Health Institute (Institutional Review Board, IHI/IRB/No 38-2015) as well as the National Institute for Medical Research, Tanzania (Ref. NIMR/HQ/R.8a/Vol. IX/2242). All three committees waived informed consent.

The study was performed according to GCP guidelines.

All manually filed log forms from patients seen between July 2016 and June 2017 were reviewed and data (date of visit, address, age, sex, diagnosis, hospitalization, pregnancy, HIV status, insurance status) were transferred into an electronic database. If a patient had several diagnoses, all diagnoses were captured and the number of diagnoses was noted. The range of 102 different single diagnoses reported was summarised into different groups for analysis. Group 1 consisted of 41 organ-based diseases, such as upper and lower respiratory tract infection, whereas Group 2 was a further simplification into 20 different disease groups according to organ or disease mechanism, such as trauma, infectious diseases (table S1 in appendix 1). Only the main diagnosis was used for grouping of diseases, additional diagnoses were reported separately.

Distance between the patient’s home and the hospital was determined using google maps or google earth. In-hospital death rates were collected by retrospective reviews of registry books from the hospital wards (medical, surgical, gynaecological and paediatric wards from January 2015 through to December 2017).

The frequencies and proportions of admission diagnoses and in-hospital mortality were recorded, calculated and reported as rates. All statistical analyses, graphs and correlations were performed using Microsoft Excel software.

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

From 1 July 2016 until 30 June 2017, all 35,903 patients attending the emergency department were included in this study. The median age was 33.6 years (range 1 day to 100 years), 57.2% of patients were female and 24.8% were children below the age of 5 years. A total of 7.5% of female patients were pregnant, and 8.9% of all patients were admitted to the ward (table 1).

Table 1 Patient characteristics (n = 35’903).

| Age in years, median (range) | 33.6 (1 day ‒ 100 years) | |

| Age category, n (%) | Age <5 years | 8’903 (24.8) |

| Age <18 years | 12’618 (35.1) | |

| Age ≥18 years | 23’156 (64.5) | |

| Age not assessed | 129 (0.4) | |

| Gender | Female sex, n (%) | 20’526 (57.2) |

| Male sex, n (%) | 15’278 (42.6) | |

| Sex not assessed, n (%) | 99 (0.3) | |

| Pregnancy, n (%) | 1’531 (7.5)* | |

| Known HIV infection, n (%) | 235 (0.7) | |

| Health insurance, n (%) | 6’400 (17.8) | |

| Number of diagnoses, n (%) | 1 | 31’158 (86.8) |

| 2 | 3’499 (9.7) | |

| 3 | 189 (0.5) | |

| >3 | 8 (0.02) | |

| None | 1’049 (2.9) | |

| Serious condition, n (%)** | 2’794 (7.8) | |

| Admitted to ward, n (%) | 3’183 (8.9) | |

| * percentage of females; ** patients with abnormal vital signs, respiratory failure, decreased consciousness, multiple trauma, bleeding or severe pain, who were managed in the emergency room | ||

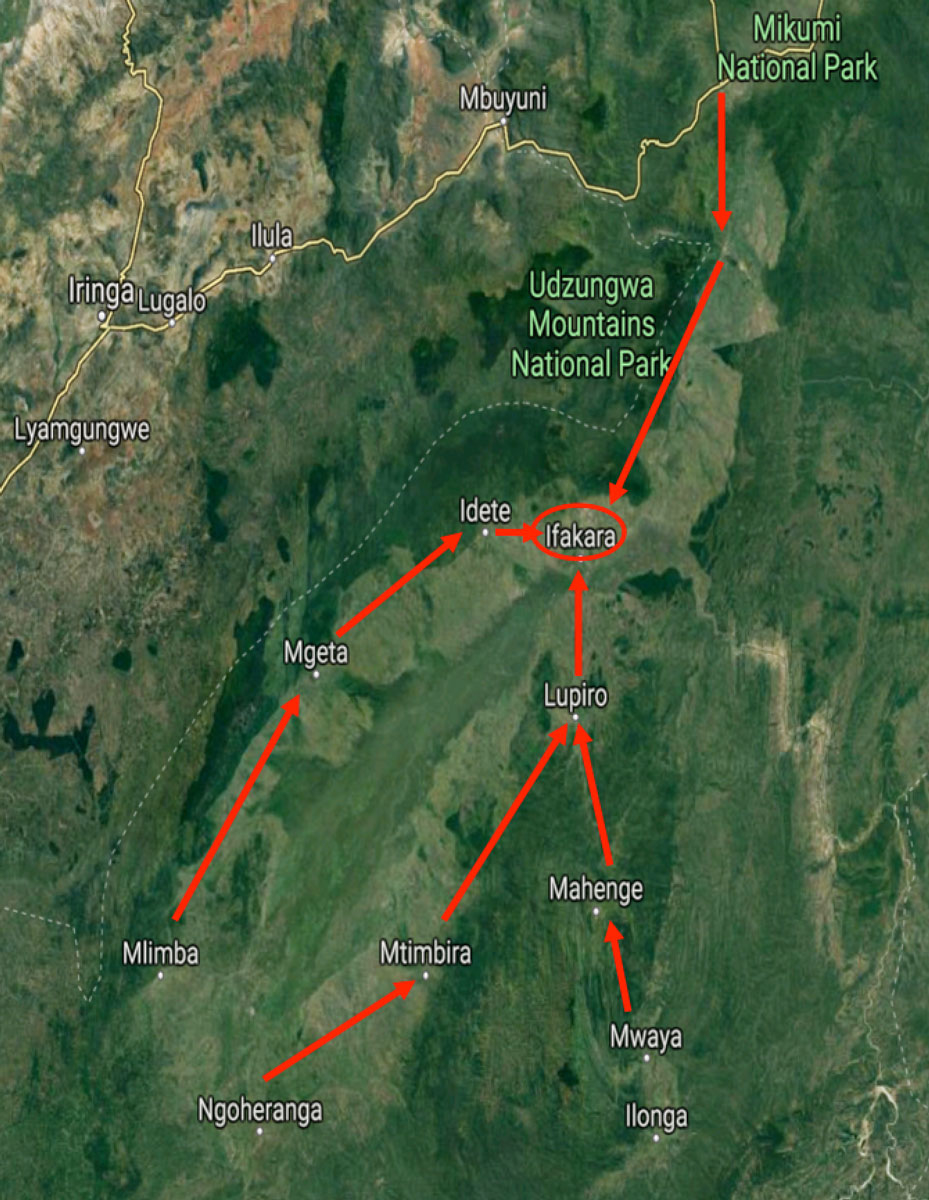

The distance from the patient’s home to the hospital was within 15 km for 69% of the patients, but some patients came from villages up to 152 km away from the hospital. During rainy season (March–May), the proportion of patients coming from far away decreased (fig. 1 and 2 ).

Figure 1 Distribution of patients according to distance home to hospital. Bars represent monthly proportions of emergency department patients with respect to distance from home to the hospital. The rainy season is marked in blue (March-May).

Figure 2 Map of the Kilombero valley and location of the villages where the patients come from.

Table 2 Diagnoses of 35’903 patients (simplified diagnosis group 1).

| Diagnosis | N | % | Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory tract infection | 4’522 | 12.6 | 1 |

| ‒ Lower respiratory tract infection | 2’843 | 7.9 | |

| ‒ Upper respiratory tract infection | 1’679 | 4.7 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 4’087 | 11.4 | 2 |

| Trauma | 3’527 | 9.8 | 3 |

| ‒ Fracture or dislocation | 1’257 | 3.5 | |

| Undifferentiated febrile illness | 1’938 | 5.4 | 4 |

| Malaria | 1’870 | 5.2 | 5 |

| Gastroenteritis/other gastrointenstinal infection | 1’755 | 4.9 | 6 |

| Dyspepsia | 1’384 | 3.9 | 7 |

| Hypertensive emergency | 1’148 | 3.2 | 8 |

| Skin diseases | 1’293 | 3.6 | 9 |

| No diagnosis | 1’049 | 2.9 | 10 |

| Gynaecological disease | 1’016 | 2.8 | 11 |

| Sexually transmitted diseases | 1’000 | 2.8 | 12 |

| Pregnancy complications | 934 | 2.6 | 13 |

| Heart failure | 700 | 1.9 | 14 |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 627 | 1.7 | 15 |

| Other abdominal diseases | 614 | 1.7 | 16 |

| Other ear/nose/throat diseases | 612 | 1.7 | 17 |

| Cellulitis and other soft tissue infections | 605 | 1.7 | 18 |

| Anaemia | 536 | 1.5 | 19 |

| Arthritis | 506 | 1.4 | 20 |

| Tuberculosis | 445 | 1.2 | 21 |

| Kidney disease | 441 | 1.2 | 22 |

| Other neurological diseases | 431 | 1.2 | 23 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease / asthma | 383 | 1.1 | 24 |

| Ophthalmologic diseases | 296 | 0.8 | 25 |

| Diabetic emergency | 249 | 0.7 | 26 |

| Urological diseases | 248 | 0.7 | 27 |

| Otitis media | 213 | 0.6 | 28 |

| Sepsis | 209 | 0.6 | 29 |

| Psychiatric diseases | 196 | 0.5 | 30 |

| Acute abdomen | 162 | 0.5 | 31 |

| Cancer | 159 | 0.4 | 32 |

| Epilepsy | 121 | 0.3 | 33 |

| Allergy | 108 | 0.3 | 34 |

| Liver disease | 104 | 0.3 | 35 |

| Stroke | 96 | 0.3 | 36 |

| Malnutrition | 67 | 0.2 | 37 |

| Meningitis | 25 | 0.1 | 38 |

The distribution of the main diseases diagnosed in the emergency department according the simplified group 2 is shown in figure 3. The most common disease groups were of infectious origin (46.3%), trauma (9.8%), abdominal diseases (6.0%), gynaecological / pregnancy-related problems (5.4%), and cardiovascular diseases (5.3%). Within the more detailed group 1 classification the most common first five diagnoses were respiratory tract infections (12.6%), urinary tract infection (11.4%), trauma (9.8%), undifferentiated febrile illness (5.4%) and confirmed malaria (5.2%) (table 2).

Figure 3 Distribution of Primary Diagnosis (Group 2) within 35,903 patients (July 2016-June 2017). The pie shows the overall distribution of diseases in percentages according to a simplified diagnosis group. ENT: ear/nose/throat

Table 3 shows the 15 leading main diagnoses in different age groups. In children below the age of 5 years (n = 8902), the leading diagnosis (group 1) was lower respiratory tract infection (16.1%). In patients who were 5 to 17 years old (n = 3716), it was trauma (21.6%), and in adults who were 18 to 50 years old (n = 17,117), urinary tract infection (13.5%) was most common. In adults who were >50 years old (n = 6039), the most common diagnosis was hypertensive emergency (12.4%). We observed seasonality in the occurrence of respiratory tract infections, confirmed malaria, and trauma: there was a peak of respiratory tract infections in April in the middle of the rainy season, and a peak of malaria in August, 3 months after the end of the rainy season. The majority of trauma cases occurred during the dry season (fig. 4 and table 4). The most common injuries of the 3527 trauma patients were bone fractures (28.3%), joint dislocations (7.4%) and soft-tissue injuries (44.9%). Unfortunately, the reasons for trauma were not recorded in 75.6% of the cases and traffic accidents were not specifically reported, despite the fact that they probably constitute the majority of trauma causes. The leading documented causes of trauma cases were animal encounters (5.8%) and violence (n = 164, 4.6%) with a total of 50 reported rape incidents during this study period.

Table 3 Most frequent diagnoses in different age groups (simplified diagnosis group 1). A total of 129 patients are not included in the table, because their age was not assessed. In adults >50 years, GI-infections and urological diseases are of equal ranking.

| Children <5 years (n = 8902) | Children 5-17 years (n = 3716) | Adults 18-50 years (n = 17117) | Adults >50 years (n = 6039) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Disease | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |||

| 1 | LRTI | 1429 | 16.1 | Trauma | 802 | 21.6 | UTI | 2308 | 13.5 | Hypertensive emergency | 749 | 12.4 |

| 2 | URTI | 1295 | 14.5 | UTI | 396 | 10.7 | Trauma | 1906 | 11.1 | UTI | 484 | 8.0 |

| 3 | UTI | 884 | 9.9 | Undifferentiated febrile illness | 263 | 7.1 | Pregnancy complications | 881 | 5.1 | Trauma | 442 | 7.3 |

| 4 | GI infections | 869 | 9.8 | Malaria | 260 | 7.0 | Gynaecological disease | 877 | 5.1 | Heart failure | 389 | 6.4 |

| 5 | Malaria | 672 | 7.5 | LRTI | 212 | 5.7 | STDs | 866 | 5.1 | LRTI | 367 | 6.1 |

| 6 | Undifferentiated febrile illness | 555 | 6.2 | ENT disease | 166 | 4.5 | Undifferentiated febrile illness | 865 | 5.1 | Dyspepsia | 329 | 5.4 |

| 7 | Skin disease | 480 | 5.4 | GI infections | 158 | 4.3 | LRTI | 830 | 4.8 | Undifferentiated febrile illness | 247 | 4.1 |

| 8 | Trauma | 386 | 4.3 | Skin diseases | 153 | 4.1 | Dyspepsia | 825 | 4.8 | Arthritis | 236 | 3.9 |

| 9 | Dyspepsia | 165 | 1.9 | Anaemia | 109 | 2.9 | Malaria | 726 | 4.2 | Malaria | 208 | 3.4 |

| 10 | Soft tissue infection | 152 | 1.7 | URTI | 100 | 2.7 | GI infections | 553 | 3.2 | GI infection | 168 | 2.8 |

| 11 | Sepsis | 153 | 1.7 | Soft tissue infections | 92 | 2.5 | Skin diseases | 536 | 3.1 | Urological diseases | 168 | 2.8 |

| 12 | Other abdominal disease | 146 | 1.6 | Asthma | 68 | 1.8 | ENT disease | 417 | 2.4 | Musculoskeletal pain | 161 | 2.7 |

| 13 | Anaemia | 139 | 1.6 | Musculoskeletal pain | 62 | 1.7 | Hypertensive emergency | 380 | 2.2 | Other abdominal disease | 140 | 2.3 |

| 14 | ENT disease | 89 | 1.0 | Other abdominal disease | 61 | 1.6 | Musculoskeletal pain | 320 | 1.9 | Diabetic emergency | 136 | 2.3 |

| 15 | Allergy | 47 | 0.5 | Dyspepsia | 60 | 1.6 | Kidney disease | 274 | 1.6 | Tuberculosis | 128 | 2.1 |

| LRTI: lower respiratory tract infection; URTI: upper respiratory tract infection; UTI: urinary tract infection; GI-infection: gastroenteritis and other intestinal infections; STDs: sexually transmitted diseases; ENT-diseases: ear-nose-throat diseases. | ||||||||||||

Figure 4 Incidence of the five most common diagnoses per 1000 patients per month. Monthly incidences of the five most common diseases, diagnosed at the emergency department in 35’903 patients from July 2016 through to June 2017. ‒ RTI: respiratory tract infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; UFI, undifferentiated febrile illnesses

Table 4 Description of trauma cases.

| Trauma patients (n = 3’527) | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patients characteristics | ||

| Female | 1429 | 40.5% |

| Median age, years (range) | 25 | 0.05-98 |

| Hospitalisation | 480 | 13.6% |

| Serious condition | 532 | 15.1% |

| Injuries | ||

| Skin and soft tissue injury | 1582 | 44.9% |

| Fracture | 997 | 28.3% |

| Bone or joint dislocation | 260 | 7.4% |

| Multiple injuries | 175 | 5.0% |

| Head injury | 172 | 4.9% |

| Chest injury | 70 | 2.0% |

| Abdominal injury | 24 | 0.7% |

| Eye/ear/nose/mouth injury | 22 | 0.6% |

| Spine injury | 21 | 0.6% |

| Pelvic injury | 5 | 0.1% |

| Not defined | 199 | 5.6% |

| Trauma mechanism | ||

| Trauma after animal encounter | 204 | 5.8% |

| ‒ Dog | 127 | |

| ‒ Snake | 33 | |

| ‒ Crocodile | 8 | |

| ‒ Other/non reported | 36 | |

| Human violence | 164 | 4.6% |

| ‒ Assault | 81 | |

| ‒ Rape | 50 | |

| ‒ Bite | 24 | |

| ‒ Other | 9 | |

| Burn (fire, hot water) | 112 | 3.2% |

| Other | 11 | 0.3% |

| Undefined* | 2668 | 75.6% |

*road traffic accidents and falls from trees

A total of 3499 patients (9.7%) had a second diagnosis and 189 (0.5%) had a third diagnosis. The most common second and third diagnoses were dyspepsia (n = 360), anaemia (n = 347), gastroenteritis and other intestinal infections (n = 306), urinary tract infection (n = 239), skin diseases (n = 225) and hypertensive emergency (n = 224)

In 2015, the documented in-hospital mortality rate was 5. 6% (8400 admissions, 467 deaths). In 2016, it was 6.6% (6310 admissions, 415 deaths), and in 2017 7.6% (5653 admissions, 427 deaths).

This is the first report on the distribution of clinically diagnosed disorders in patients presenting to an emergency department of a referral hospital situated in rural sub-Saharan Africa. The most common disorders were of infectious or traumatic origin. The five most common diagnoses were respiratory and urinary tract infection, trauma, undifferentiated febrile illness and malaria. In the age group of >50 years, hypertensive emergency was the most frequent diagnosis, reflecting the importance of noncommunicable diseases in this setting and age group. Lower and upper respiratory tract infections were the most common diagnoses in children <5 years. Respiratory tract infections typically occurred during the rainy season, whereas malaria was diagnosed mostly 3 months after the rainy season and trauma most commonly during the dry season.

After the implementation of the emergency department, we did not note a reduction of the in-hospital mortality rate during the study period, in contrast to findings in urban settings [9–11].

The seasonal variation of the incidence of respiratory tract infections is a well-known phenomenon. Studies from tropical regions such as Africa, Asia and South America showed a peak of respiratory tract infections and respiratory viruses – especially respiratory syncytial virus and influenza virus – during the rainy season [12, 13]. Because of a lack of adequate diagnostics, we were unable to identify the pathogens causing respiratory tract infections. However, in a study done in our hospital and in an urban hospital in Dar es Salaam in 2008, which included febrile children 2 months to 10 years of age, acute respiratory tract infection was the most frequent diagnosis in 625 out of 1005 (62.2%) febrile episodes. Viral pathogens were common and were found in 81% of all respiratory tract infections, in 89% of the cases of clinically diagnosed pneumonia and in 77% of radiologically confirmed pneumonia cases. The most common viruses detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) were rhinovirus, influenza virus, adenovirus, coronavirus, bocavirus and respiratory syncytial virus [14]. Similar viruses were found in 73% of children <3 years of age with upper- and lower respiratory tract infections in a hospital in Ouagadougo, Burkina Faso, and bacteria were detected in one third of the cases only [15].

The high number of urinary tract infections corresponds to other studies on emergency department diagnoses. In a study from the United States, urinary tract infection was present in 25.3% of all infectious disease-related emergency department visits of adults aged >65years [16]. The prevalence of urinary tract infections in an emergency unit in Nigeria was 9% in febrile children <5 years [17]. The incidence for urinary tract infection in girls by the age of 7 years has been reported to be up to 7.8% in Scandinavia [18]. On the other hand, overdiagnosis and overtreatment of elderly women diagnosed with urinary tract infection in an emergency department without confirmation by urine culture was reported to be present in half of the patients [19]. Considering this, overdiagnosis of urinary tract infection in our emergency department is possible, and some of those patients who received this diagnosis might have suffered from another disease.

All malaria cases were confirmed with blood slides or malaria rapid diagnostic tests, which have good sensitivity and specificity of more than 90% [20]. The high number of malaria cases presenting at the emergency department reflects the ongoing burden of this disease [21]. We observed peak numbers of malaria cases in August, 3 months after the end of the rainy season, when temperatures increase to moderate levels. The clustering of malaria cases 2 to 3 months after periods of increased rainfall has been reported previously [22, 23].

Undifferentiated febrile illness was more frequent than confirmed malaria in all age groups except in children <5 years old, and was one of the leading diagnoses, especially in 5- to 17-year-old patients, were it was present in 7.1%. This is in line with other reports on burden of febrile illnesses in sub-Saharan Africa [24].

Because of the absence of microbiological diagnostic methods such as bacterial cultures, PCR and serological tests, we were not able to define the aetiology of these diseases, but this should represent an aim for future investigations. In very young children, it is likely that most of these cases were of viral aetiology [14]. In addition, acute bacterial zoonoses such as rickettsioses, leptospirosis, Q-fever and brucellosis might represent underappreciated causes. This was recently unveiled in studies from south-east Asia and from northern Tanzania, where zoonotic diseases were involved in 26% of admitted adults and children with non-malarial febrile illnesses [25–27]. This study also documented bloodstream infections in 10% of patients, but the actual causes of febrile illnesses remained unknown in one third of adults and two thirds of children, despite careful microbiological evaluation [25]. These findings highlight the importance of performing causes-of-fever studies and sero-epidemiological surveys to elucidate better the aetiologies of common febrile illnesses.

Trauma was the third most common cause for a disorder, and occurred in almost 10%. More than one third of trauma cases had a bone fracture or dislocation, and trauma was the most common diagnosis in 5- to 17-year-old children. Of note, there were 164/3527 (4.6%) documented cases of trauma due to human violence, including 50 cases of rape. However, the actual number of violence cases is likely to be higher, as a result of underreporting of violence against children, especially girls [28, 29].

Trauma cases occurred almost twice as frequently as malaria cases. This corresponds to a recent 1-day survey in all 105 Tanzanian district and regional hospitals, where 9.7% of the patients presented with trauma-related complaints [30]. Globally, an estimated 973 million people sustained injuries that warranted healthcare in 2013, and accounted for 10% of the global burden of disease [31]. More than 5 million people die each year as a result of injuries. This accounts of 9% of the world deaths, notably 1.7 times the number of fatalities resulting from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria combined. About 90% of injury-related deaths occur in low-and middle income countries [32]. Advanced trauma live support (ATLS), including extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST) to detect bleeding and pneumothorax, has been implemented in our emergency department [33]. However, data that education in ATLS is associated with lower mortality are lacking [34, 35]. On the other hand, trauma systems (i.e., organised, regional, multidisciplinary response to injury) have been shown to be associated with reduced mortality, reduced disability and reduced cost in high-income countries [36, 37]. Trauma systems do not exist in rural sub-Saharan Africa, and are urgently needed.

Cardiovascular diseases were amongst the most frequent diagnoses in adults, especially in the age group of >50 years, where hypertensive emergency was the most common diagnosis. According to WHO estimates, cardiovascular diseases are the second most common cause of death in Africa [38]. Hypertension is prevalent in urban and rural sub-Saharan Africa, mostly not treated, and rarely well controlled [39, 40]. In a cross-sectional study performed in Ifakara, the overall prevalence of hypertension was 30%, and was 40 to 70% in the age group of >50 years [41].

Despite reports of a growing burden of cancer in low- and middle-income countries [42], cancer was the diagnosis in 0.4% of the cases only. Although x-ray and ultrasound were available, we cannot exclude the possibility that cancer was missed. However, cancer was not among the 30 leading causes of global prevalence and incidence for diseases in 2016 [43].

The annual in-hospital mortality rates remained similar, between 5.6 and 7.6% from 2015 to 2017, although hospital admissions declined in recent years. This might reflect that the overall disease severity of hospitalised patients was higher as a result of improved triage, but also of a rise in hospital admission fees in 2016. These data stand in contrast to other studies, were in-hospital mortality rate decreased after implementation of a triaging system and emergency care in urban hospitals in sub-Saharan Africa [5–8]. Data about mortality in our study were retrospectively retrieved from register books from the wards, which might not have been completed properly. Other reasons might be the lack of a trauma system and intensive care unit, and distance to the hospital and lack of a rapid transport by ambulances, leading to late presentation. Delayed presentation has been shown to be associated with a poor outcome in sepsis, trauma and pregnancy-related problems [44–47], and might have outweighed the benefit of an emergency department.

This study has limitations: First, the reported data relies on the clinical judgment of clinicians, which was based on clinical skills, available point-of-care tests, conventional x-ray and ultrasound. All clinicians were experienced and trained in emergency medicine during the study period. Second, the reporting was not standardised, such as according to ICD-10 codes, leading to possible reporting bias. This was most visible in the reporting of trauma mechanism, where we found comparatively detailed documentation on violence or animal encounters and little documentation on road accidents. By introducing a standardised categorisation into groups wherever possible, we attempted to address the possible bias. Third, triage with documentation of the South African triage scale score was not performed over 24 hours, but during regular working hours only. Thus, we could not analyse this score conclusively. Fourth, we were confronted with limited outcome measures to assess the impact of the emergency department: information on waiting time, time to diagnosis, time to treatment, or death in the emergency department was not available. Since in-hospital mortality depends on many factors, it does not represent an ideal outcome measure to evaluate the possible benefit of an emergency department. Fifth, we had no reliable data about patients attending the emergency department in 2015. Thus, we could not compare the number of admissions per number of patients. This information could have supported the theory that better triage contributed to in-hospital mortality. Finally, this was a single centre study and therefore findings might not be generalisable to other settings.

In conclusion, infectious diseases and trauma were the most common emergency department diagnoses during 1 year, with varying seasonal occurrence of respiratory tract infections, malaria and trauma. A substantial number of the patients suffered from a febrile illness whose cause remained unknown because of lack of diagnostic methods. Therefore, cheap and easy implementable diagnostic methods are needed. The implementation of trauma systems including pre-hospital emergency care, rapid transport with ambulances, surgery and intensive care medicine is urgently needed in rural sub-Saharan Africa.

Table S1 Classification of diagnoses

| Diagnoses (n = 102) | Summarised diagnoses group 1 (shown in tables 2 and 3) (n = 41) | Summarised diagnoses group 2 (shown in figure 2 ) (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|

| Acute Bronchitis | Respiratory tract infection ‒ lower respiratory tract infection ‒ upper respiratory tract infection |

Infectious diseases |

| Pneumonia | ||

| Other acute respiratory problems | ||

| Upper respiratory tract Infections | ||

| Urinary tract infection | Urinary tract infection | |

| Fever of not defined origin | Fever of not defined origin | |

| Malaria | Malaria | |

| Diarrhoea | Gastroenteritis/other intestinal infections | |

| Gastroenteritis | ||

| Infection with helminths, parasites | ||

| Food poisoning | ||

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | Sexually transmitted diseases (STD) | |

| Other sexually transmitted disease | ||

| Cellulitis | Cellulitis and other soft tissue infections | |

| Abscess | ||

| Myositis | ||

| Wound infection | ||

| Sepsis | Sepsis | |

| Meningitis | Meningitis | |

| Tuberculosis | Tuberculosis | |

| HIV | HIV | |

| Trauma, not defined | Trauma | Trauma |

| Trauma due to animal encounter | ||

| Trauma due to fall of tree | ||

| Trauma due to other mechanism | ||

| Trauma due to traffic accident | ||

| Trauma due to violence | ||

| Trauma with dislocation | ||

| Trauma with fracture | ||

| Trauma with soft tissue injury | ||

| Acute abdomen | Acute abdomen | Abdominal diseases |

| Appendicitis | ||

| Dyspepsia | Dyspepsia | |

| GI problems (undefined) | Other abdominal diseases | |

| GI obstruction | ||

| Haemorrhoids | ||

| Hernia, rectal prolapse | ||

| Other GI problems | ||

| Hypertensive emergency | Hypertensive emergency | Cardiovascular diseases |

| Heart failure | Heart failure | |

| Stroke | Stroke | |

| Gynaecological cyst | Gynaecological disease | Gynaecological and pregnancy-related diseases |

| Gynaecological problems (undefined) | ||

| Gynaecological problems, other | ||

| Gynaecological tumor | ||

| Menstruation abnormalities | ||

| Abortion | Pregnancy complications | |

| Hyperemesis gravidarum | ||

| Physiological pregnancy problems | ||

| Preeclampsia | ||

| Pregnancy problems (undefined) | ||

| Pregnancy problems, others | ||

| Lumbago | Musculoskeletal pain | Diseases of joints, bones and muscles |

| Other musculoscelettal disorders | ||

| Arthritis | Arthritis | |

| Lipoma | Skin diseases | Diseases of skin and mucous membranes |

| Oral diseases | ||

| Skin diseases unspecified | ||

| Other skin diseases | ||

| Otitis media | Otitis media | ENT-and ophthalmological diseases |

| Cerumen impaction | Other ENT diseases | |

| Tonsillitis | ||

| Epistaxis | ||

| Goitre | ||

| Laryngitis | ||

| Nasal polyp | ||

| Otitis media | ||

| Rhinitis | ||

| Sinusitis | ||

| Other ear/nose/throat diseases | ||

| Ophthalmological diseases | Ophthalmological diseases | |

| Asthma | COPD/Asthma | Lung diseases |

| Chronic obstructive lung disease | ||

| Other lung diseases | Other lung diseases | |

| Epilepsy | Epilepsy | Neurological diseases |

| Bell's Palsy | Other neurological diseases | |

| Guillain Barré | ||

| Polyneuropathy | ||

| Other neurological disease | ||

| Hypoglycaemia | Diabetic emergency | Diabetic emergency |

| Ketoacidosis | ||

| Anaemia | Anaemia/Sickle cell disease | Haematological diseases |

| Sickle cell disease | ||

| Malnutrition | Malnutrition | Malnutrition |

| Vitamin deficiency | ||

| Liver disease | Liver disease | Liver disease |

| Kidney disease | Kidney disease | Kidney disease |

| Cancer | Cancer | Cancer |

| Urological diseases | Urological diseases | Urological diseases |

| Allergy | Allergy | Allergy |

| Psychosis | Psychiatric diseases | Psychiatric diseases |

| Panic attack | ||

| other psychiatric disorders | ||

| Check-up | Other diseases | Other diseases |

| Dehydration | ||

| Foreign body | ||

| Lymphadenopathy | ||

| No diagnosis | ||

| Not readable | ||

| Other disease | ||

| Tonge tie | ||

| Dead body | Dead body |

Symphasis Foundation, Zürich, Switzerland; Hella Langer Foundation, Gräfelfing, Germany; Ernst Göhner Foundation, Zug, Switzerland

None

1 Kobusingye OC , Hyder AA , Bishai D , Hicks ER , Mock C , Joshipura M . Emergency medical systems in low- and middle-income countries: recommendations for action. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83(8):626–31.

2 Ouma PO , Maina J , Thuranira PN , Macharia PM , Alegana VA , English M , et al. Access to emergency hospital care provided by the public sector in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015: a geocoded inventory and spatial analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(3):e342–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30488-6

3 Obermeyer Z , Abujaber S , Makar M , Stoll S , Kayden SR , Wallis LA , et al.; Acute Care Development Consortium. Emergency care in 59 low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93(8):577–586G. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.14.148338

4 Baker T , Lugazia E , Eriksen J , Mwafongo V , Irestedt L , Konrad D . Emergency and critical care services in Tanzania: a survey of ten hospitals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):140. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-13-140

5 Molyneux E , Ahmad S , Robertson A . Improved triage and emergency care for children reduces inpatient mortality in a resource-constrained setting. Bull World Health Organ. 2006;84(4):314–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.04.019505

6 Clark M , Spry E , Daoh K , Baion D , Skordis-Worrall J . Reductions in inpatient mortality following interventions to improve emergency hospital care in Freetown, Sierra Leone. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e41458. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041458

7 Robison JA , Ahmad ZP , Nosek CA , Durand C , Namathanga A , Milazi R , et al. Decreased pediatric hospital mortality after an intervention to improve emergency care in Lilongwe, Malawi. Pediatrics. 2012;130(3):e676–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0026

8 Sawe HR , Mfinanga JA , Mwafongo V , Reynolds TA , Runyon MS . Trends in mortality associated with opening of a full-capacity public emergency department at the main tertiary-level hospital in Tanzania. Int J Emerg Med. 2015;8(1):24. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-015-0073-4

9 Twomey M , Wallis LA , Thompson ML , Myers JE . The South African Triage Scale (adult version) provides reliable acuity ratings. Int Emerg Nurs. 2012;20(3):142–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ienj.2011.08.002

10 Sunyoto T , Van den Bergh R , Valles P , Gutierrez R , Ayada L , Zachariah R , et al. Providing emergency care and assessing a patient triage system in a referral hospital in Somaliland: a cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):531. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0531-3

11 Dalwai M , Valles P , Twomey M , Nzomukunda Y , Jonjo P , Sasikumar M , et al. Is the South African Triage Scale valid for use in Afghanistan, Haiti and Sierra Leone? BMJ Glob Health. 2017;2(2):e000160. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2016-000160

12 Shek LP , Lee BW . Epidemiology and seasonality of respiratory tract virus infections in the tropics. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2003;4(2):105–11. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-0542(03)00024-1

13 Ho NT , Thompson C , Nhan LNT , Van HMT , Dung NT , Tran My P , et al. Retrospective analysis assessing the spatial and temporal distribution of paediatric acute respiratory tract infections in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e016349. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-016349

14 D’Acremont V , Kilowoko M , Kyungu E , Philipina S , Sangu W , Kahama-Maro J , et al. Beyond malaria--causes of fever in outpatient Tanzanian children. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(9):809–17. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1214482

15 Ouédraogo S , Traoré B , Nene Bi ZA , Yonli FT , Kima D , Bonané P , et al. Viral etiology of respiratory tract infections in children at the pediatric hospital in Ouagadougou (Burkina Faso). PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110435. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0110435

16 Goto T , Yoshida K , Tsugawa Y , Camargo CA, Jr , Hasegawa K . Infectious Disease-Related Emergency Department Visits of Elderly Adults in the United States, 2011-2012. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(1):31–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13836

17 Musa-Aisien AS , Ibadin OM , Ukoh G , Akpede GO . Prevalence and antimicrobial sensitivity pattern in urinary tract infection in febrile under-5s at a children’s emergency unit in Nigeria. Ann Trop Paediatr. 2003;23(1):39–45. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1179/000349803125002850

18 Zorc JJ , Kiddoo DA , Shaw KN . Diagnosis and management of pediatric urinary tract infections. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(2):417–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.18.2.417-422.2005

19 Gordon LB , Waxman MJ , Ragsdale L , Mermel LA . Overtreatment of presumed urinary tract infection in older women presenting to the emergency department. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(5):788–92. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12203

20 Abba K , Deeks JJ , Olliaro P , Naing CM , Jackson SM , Takwoingi Y , et al. Rapid diagnostic tests for diagnosing uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria in endemic countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(7):CD008122. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008122.pub2

21WHO. World Malaria Report 2017. 2017.

22 Kipruto EK , Ochieng AO , Anyona DN , Mbalanya M , Mutua EN , Onguru D , et al. Effect of climatic variability on malaria trends in Baringo County, Kenya. Malar J. 2017;16(1):220. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1848-2

23 Reiner RC, Jr , Geary M , Atkinson PM , Smith DL , Gething PW . Seasonality of Plasmodium falciparum transmission: a systematic review. Malar J. 2015;14(1):343. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-015-0849-2

24 Feikin DR , Olack B , Bigogo GM , Audi A , Cosmas L , Aura B , et al. The burden of common infectious disease syndromes at the clinic and household level from population-based surveillance in rural and urban Kenya. PLoS One. 2011;6(1):e16085. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0016085

25 Crump JA , Morrissey AB , Nicholson WL , Massung RF , Stoddard RA , Galloway RL , et al. Etiology of severe non-malaria febrile illness in Northern Tanzania: a prospective cohort study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(7):e2324. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0002324

26 Blacksell SD , Kantipong P , Watthanaworawit W , Turner C , Tanganuchitcharnchai A , Jintawon S , et al. Underrecognized arthropod-borne and zoonotic pathogens in northern and northwestern Thailand: serological evidence and opportunities for awareness. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2015;15(5):285–90. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1089/vbz.2015.1776

27 Bonell A , Lubell Y , Newton PN , Crump JA , Paris DH . Estimating the burden of scrub typhus: A systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11(9):e0005838. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0005838

28 García-Moreno C , Zimmerman C , Morris-Gehring A , Heise L , Amin A , Abrahams N , et al. Addressing violence against women: a call to action. Lancet. 2015;385(9978):1685–95. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61830-4

29 Barr AL , Knight L , Franҫa-Junior I , Allen E , Naker D , Devries KM . Methods to increase reporting of childhood sexual abuse in surveys: the sensitivity and specificity of face-to-face interviews versus a sealed envelope method in Ugandan primary school children. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2017;17(1):4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0110-2

30 Sawe HR , Mfinanga JA , Mbaya KR , Koka PM , Kilindimo SS , Runyon MS , et al. Trauma burden in Tanzania: a one-day survey of all district and regional public hospitals. BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17(1):30. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12873-017-0141-6

31 Haagsma JA , Graetz N , Bolliger I , Naghavi M , Higashi H , Mullany EC , et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj Prev. 2016;22(1):3–18. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041616

32WHO. Injuries and violence: The facts 2014. appswhoint/iris/bitstream/10665/149798/1/9789241508018_engpdf. 2014.

33 https://www.scribd.com/document/367004515/Advanced-Trauma-Life-Support-ATLS-Student-Course-Manual-2018 ACoSATLSAScmte.

34 Abu-Zidan FM . Advanced trauma life support training: How useful it is? World J Crit Care Med. 2016;5(1):12–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v5.i1.12

35 Moore L , Champion H , Tardif PA , Kuimi BL , O’Reilly G , Leppaniemi A , et al.; International Injury Care Improvement Initiative. Impact of Trauma System Structure on Injury Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World J Surg. 2018;42(5):1327–39. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-017-4292-0

36 Celso B , Tepas J , Langland-Orban B , Pracht E , Papa L , Lottenberg L , et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing outcome of severely injured patients treated in trauma centers following the establishment of trauma systems. J Trauma. 2006;60(2):371–8, discussion 378. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ta.0000197916.99629.eb

37 Gabbe BJ , Simpson PM , Sutherland AM , Wolfe R , Fitzgerald MC , Judson R , et al. Improved functional outcomes for major trauma patients in a regionalized, inclusive trauma system. Ann Surg. 2012;255(6):1009–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e31824c4b91

38WHO. Global Health Estimates 2015: Death by Cause A, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2015. Geneva, World Health Organization. 2016.

39 Ataklte F , Erqou S , Kaptoge S , Taye B , Echouffo-Tcheugui JB , Kengne AP . Burden of undiagnosed hypertension in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2015;65(2):291–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04394

40 Price AJ , Crampin AC , Amberbir A , Kayuni-Chihana N , Musicha C , Tafatatha T , et al. Prevalence of obesity, hypertension, and diabetes, and cascade of care in sub-Saharan Africa: a cross-sectional, population-based study in rural and urban Malawi. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2018;6(3):208–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30432-1

41Ramaiya AGE. HIV and NDC: The burden of chronic disease in rural Tanzania. available at: https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B7y5ETfTjl4xREwyQUg0SkgzR0k/edit. Spotlight 2014(19).

42 Farmer P , Frenk J , Knaul FM , Shulman LN , Alleyne G , Armstrong L , et al. Expansion of cancer care and control in countries of low and middle income: a call to action. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1186–93. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61152-X

43 Disease GBD , Injury I , Prevalence C ; GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–59. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2

44 Jarman MP , Castillo RC , Carlini AR , Kodadek LM , Haider AH . Rural risk: Geographic disparities in trauma mortality. Surgery. 2016;160(6):1551–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2016.06.020

45Jarman MP, Curriero FC, Haut ER, Pollack Porter K, Castillo RC. Associations of Distance to Trauma Care, Community Income, and Neighborhood Median Age With Rates of Injury Mortality. JAMA Surg. 2018.

46 Hanson C , Cox J , Mbaruku G , Manzi F , Gabrysch S , Schellenberg D , et al. Maternal mortality and distance to facility-based obstetric care in rural southern Tanzania: a secondary analysis of cross-sectional census data in 226 000 households. Lancet Glob Health. 2015;3(7):e387–95. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(15)00048-0

47 Pruinelli L , Westra BL , Yadav P , Hoff A , Steinbach M , Kumar V , et al. Delay Within the 3-Hour Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guideline on Mortality for Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(4):500–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000002949

MR got the grant for the project. MR and MW contributed to design the study, to data collection, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. EM contributed to data collection, data analysis, and writing the manuscript. GM, FK, YT, JN, and WG contributed to data collection. HJ contributed to data collection and data analysis. NS contributed to data analysis. SK, CH contributed to design the study and write the manuscript. DHP contributed to writing the manuscript.

Symphasis Foundation, Zürich, Switzerland; Hella Langer Foundation, Gräfelfing, Germany; Ernst Göhner Foundation, Zug, Switzerland

None