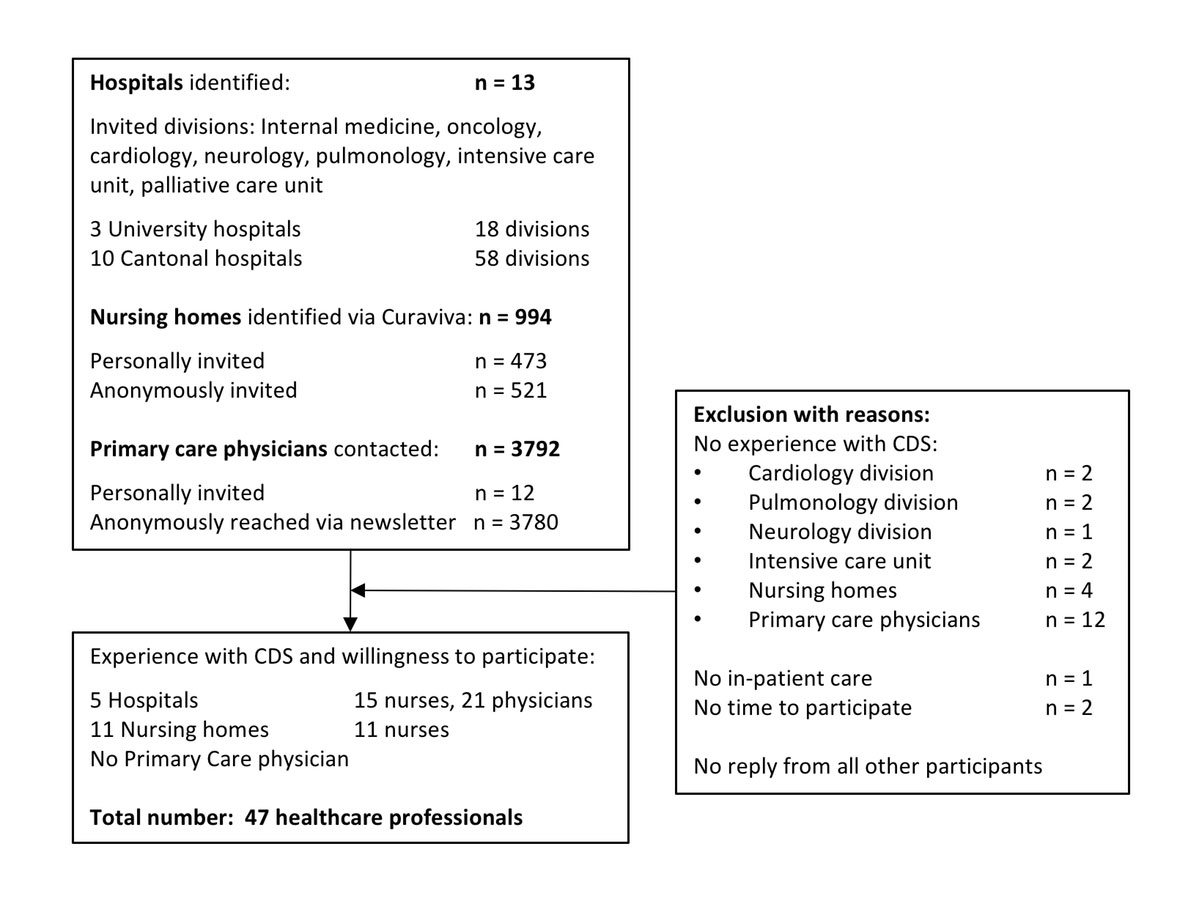

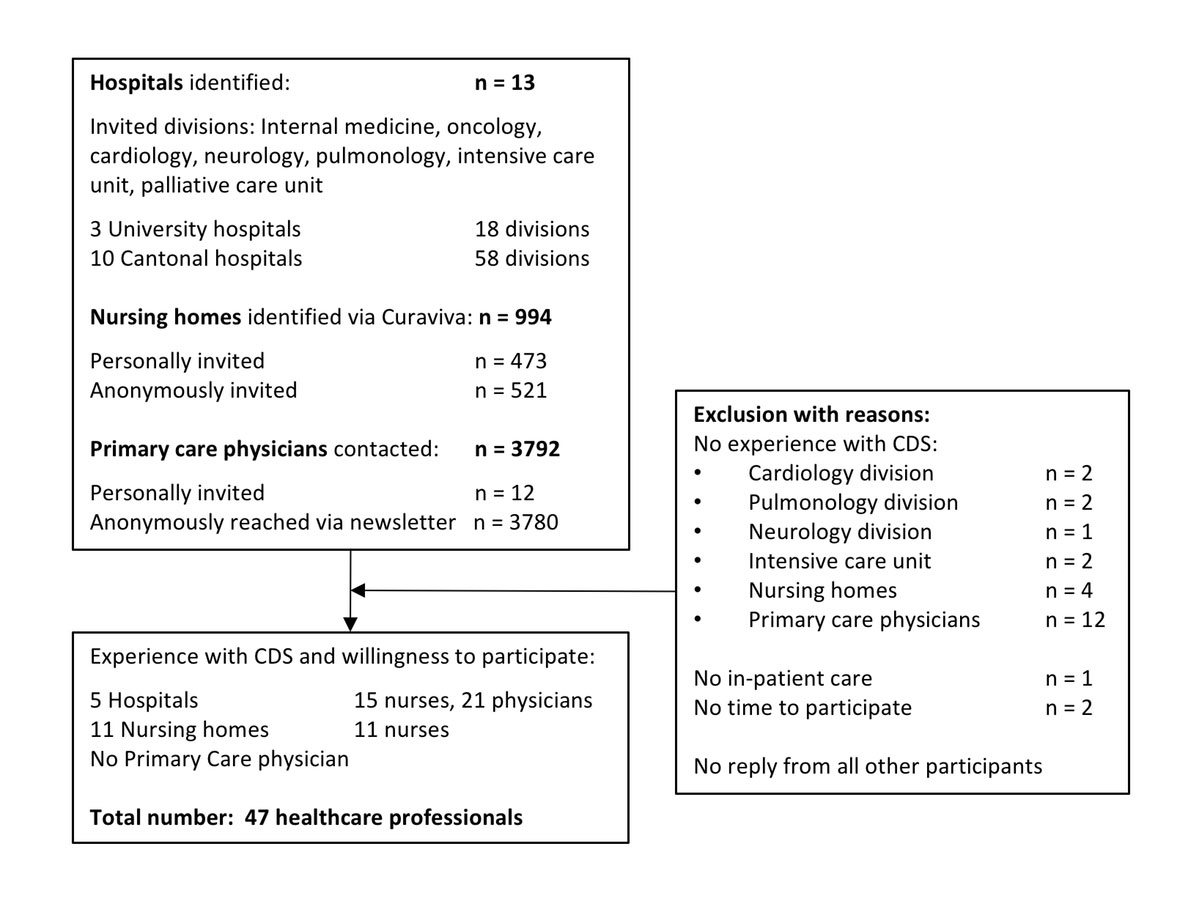

Figure 1 Recruitment process of focus group participants.

CDS = continuous deep sedation until death

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14657

In end-of-life care, alleviation of patients’ unbearable suffering is everyday clinical practice. Where conventional symptom control is not sufficient, “palliative sedation” can be considered. According to a patient’s need, palliative sedation is mild or deep and induced intermittently or continuously until death [1]. Population-wide studies have estimated the overall prevalence of such continuous deep sedation until death to vary between 2.5 and 18.3% [2–8], with one of the highest incidences and strongest increases observed in Switzerland from 4.7% in 2001 to 17.5% in 2013 [7, 9].

Since 1963 terminology has become increasingly complex, leading to a diversity of terms used [10]. To standardise the procedure for this sedation, several practice guidelines have been developed [11]. According to the European Association of Palliative Care (EAPC), palliative sedation is only indicated when the professionals’ intention is to relieve patients’ refractory suffering as option of last resort, not any attempt to hasten death [12]. Benzodiazepines are the medication of first choice and the use of opioids is considered inappropriate [13].

Palliative sedation guidelines have predominantly been developed in the context of specialised palliative care, whereas two thirds of all deaths in Switzerland occur in acute care hospitals and long-term care facilities [14, 15]. Deviations from clinical guidelines seem likely and are caused by on-going ethical discussions around the belief that continuous deep sedation until death is life-shortening [16]. This seems particularly the case for less experienced professionals working in non-specialised settings [17]. Today, there is little evidence clarifying whether in everyday clinical practice, both within and outside of specialised palliative care, continuous deep sedation is performed according to the concept and implementation presented in the aforementioned guidelines. Therefore, we aimed to explore physicians’ and nurses’ understanding of continuous deep sedation and to unravel decision-making processes in everyday clinical practice.

We reported this study according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines [18]. To elicit healthcare professionals’ experience and perspective on continuous deep sedation until death and to foster conversations within different domains between healthcare professionals, we conducted qualitative focus groups in German-speaking Switzerland between June and October 2016. The study was approved by the Zurich Cantonal Ethics Board (KEK-StV-Nr. 23/13).

To cover the whole spectrum of healthcare professionals potentially confronted with the administration of continuous deep sedation until death, we focused on: (i) general and specialised palliative care settings defined in the Swiss framework of palliative care and (ii) care divisions that treat patients suffering from palliative care-relevant diseases based on the International Classification of Diseases-10 codes used to estimate palliative care need. We recruited physicians and nurses from hospitals, nurses from nursing homes, and family practitioners (fig. 1).

Figure 1 Recruitment process of focus group participants.

CDS = continuous deep sedation until death

In total, we identified 13 hospitals via the hospital register of the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health and included all hospitals in German-speaking Switzerland of level 1 (3 university hospitals) and level 2 (10 general hospitals, centralised support). According to palliative care relevant diseases, we sampled within the departments of internal medicine, pulmonology, cardiology, neurology, oncology and intensive care units (ICUs) (18 departments in 3 university hospitals, 58 departments in 10 cantonal general hospitals). To complete our coverage of general palliative care settings, we furthermore contacted 994 nursing homes via the Swiss association of social homes and institutions (Curaviva) and 3780 family practitioners via the Swiss association of general practitioners (mfe) as well as 12 prespecified family practitioners.

We approached eligible participants from hospitals and nursing homes by e-mailing the study invitation and information to the senior clinical staff and asking them to nominate physicians and nurses actually involved in sedation decision and administration. Invitations for family practitioners were sent to 12 preselected physicians personally and to 3780 anonymously as part of an online newsletter of the mfe.

Participants were eligible if they had been closely involved in the care or decision-making process for patients continuously deeply sedated until death in the last 3 years.

Focus groups with participants from hospitals were grouped into the core care team of continuously deeply sedated patients and if available their significant interdisciplinary collaborators. The five multi-professional focus groups were held at the respective hospitals. The two focus groups with nurses from long-term care institutions were held either in Zurich or in Olten. Each nurse represented a different long-term care institution.

All discussions were led by an independent and experienced moderator and lasted on average 90 minutes. We audiotaped each focus group and transcribed them verbatim. Two observers (SZ and MS) made notes to record the order of the individual quotes and to maintain contextual details and non-verbal expressions for data interpretation.

The moderator followed a predefined discussion guide which was pilot tested through 10 expert interviews. Previous findings of the fourfold increase of continuous deep sedation until death in German-speaking Switzerland between 2001 and 2013 were used to initiate the discussion [7]. The discussion guide consisted of open questions and prompts covering six topics derived from the EAPC framework: (i) terminology and definition; (ii) indication; (iii) decision-making process; (iv) administration and monitoring; (v) evaluation; (vi) moral concerns. To obtain terminology related differences in sedation understanding across healthcare professionals, participants were asked about the term used to describe “the administration of drugs, such as benzodiazepines and/or other sedative substances, to keep a patient in deep sedation or coma until death” [7]. From all participants, we additionally obtained information on demographics (table 1) and experience with continuous deep sedation (table 2).

Table 1 Healthcare professionals’ sociodemographics and clinical work experience. Figures are percent and (numbers) unless otherwise stated.

| Characteristics |

Total

(n = 47) |

Hospital*

(n = 36) |

Long-term care*

(n = 11) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years; mean (SD) | 47.8 | (8.9) | 46.3 | (9.0) | 52.5 | (6.5) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 63.8 | (30) | 71.0 | (21) | 30.0 | (9) |

| Male | 36.2 | (17) | 88.2 | (15) | 11.8 | (2) |

| Profession | ||||||

| Physician | 44.7 | (21) | 100 | (21) | - | |

| Nurse | 55.3 | (26) | 57.7 | (15) | 42.3 | (11) |

| Healthcare setting† | ||||||

| Nursing home / hospice | 23.4 | (11) | 0.0 | (0) | 100 | (11) |

| Palliative care unit | 27.7 | (13) | 36.1 | (13) | - | |

| Mobile palliative care | 2.1 | (1) | 2.8 | (1) | - | |

| Conciliar palliative care | 4.3 | (2) | 5.6 | (2) | - | |

| General internal medicine | 8.6 | (4) | 11.1 | (4) | - | |

| Oncology | 23.4 | (11) | 30.6 | (11) | - | |

| Intensive care unit | 6.4 | (3) | 100 | (3) | - | |

| Emergency department | 4.3 | (2) | 5.6 | (2) | - | |

| Clinical experience in years; mean years(SD)‡ | 20.4 | (9.2) | 18.3 | (8.6) | 27.0 | (7.7) |

| Palliative care experience in years; mean years(SD)‡ | 9.8 | (7.3) | 9.3 | (7.2) | 11.3 | (7.6) |

| Palliative care specialisation | ||||||

| Specialised palliative care§ | 55.3 | (26) | 80.8 | (21) | 19.2 | (5) |

| Other | 44.7 | (21) | 71.4 | (15) | 28.6 | (6) |

SD = standard deviation. * Figures are row percent if not otherwise stated. Missing data were omitted for percentages. † For healthcare settings figures are column percent. ‡ Missing data: 1 for clinical experience, 2 for palliative care experience. § Specialised palliative care includes all healthcare professionals with postgraduate palliative care training such as a Master of Advanced Studies, postgraduate training level B2.

Table 2 Healthcare professionals’ clinical experience with continuous deep sedation until death. Figures are column percent and (numbers) unless otherwise stated.

| Characteristics |

Non-specialised palliative care

(n = 21) |

Specialised palliative care*

(n = 26) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual number of patients continuously deeply sedated, mean† | 5.6 | 5.3 | ||

| Last sedated patient in months, mean months(SD)† | 8.0 | (10.2) | 7.0 | (8.4) |

| Terminology†‡ | ||||

| Palliative sedation | 53.8 | (7) | 42.9 | (9) |

| Terminal sedation | 15.4 | (2) | 57.1 | (12) |

| Continuous deep sedation | 15.4 | (2) | 9.5 | (2) |

| Symptom control / supportive care / comfort therapy | 23.1 | (3) | 4.8 | (1) |

| None | 23.1 | (3) | - | |

| Indication†‡ | ||||

| Dyspnoea | 58.8 | (10) | 56.6 | (13) |

| Delirium | 23.5 | (4) | 53.9 | (14) |

| Pain | 70.6 | (12) | 50.0 | (13) |

| Anxiety | 41.2 | (7) | 23.1 | (6) |

| Massive haemorrhage | - | 11.5 | (3) | |

| Patient’s wish | 17.7 | (3) | 7.7 | (2) |

| Other symptoms | 22.2 | (4) | 11.5 | (3) |

| Medication† | ||||

| Benzodiazepines alone | 25.0 | (4) | 87.5 | (21) |

| Opioids alone | 25.0 | (4) | - | |

| Benzodiazepines + opioids | 43.8 | (7) | 12.5 | (3) |

| Other | 6.3 | (1) | - | |

| Guidelines†‡ | ||||

| Bigorio | 11.1 | (2) | 65.4 | (17) |

| Internal | 50.0 | (9) | 53.9 | (14) |

| EAPC | 11.1 | (2) | 26.9 | (7) |

| Others | 22.2 | (4) | 26.9 | (7) |

| None | 33.3 | (6) | - | |

SD = standard deviation; EAPC=European Association of Palliative Care * Includes all healthcare professionals with postgraduate palliative care training such as a Master of Advanced Studies, postgraduate training level B2. † Missing data: 8 for annual number of sedated patients, 6 for last sedated patient, 4 for indication, 7 for medication, 3 for guidelines, 13 for terminology. Missing data were omitted for percentages. ‡ Multiple answer question – percentages may add up to more than 100.

Two coders (SZ, MS) independently analysed the transcripts according to Mayring’s qualitative content analysis using the MAXQDA software (MAXQDA Analytics Pro, version 12, 1995–2017, VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany). In a first step, we assigned all statements to pre-identified themes related to the six categories covered in the discussion guide. Based on these initial themes we inductively derived major differences between healthcare professionals’ palliative specialisation and care settings. Therefore, physicians and nurses were identified as palliative care specialists when they had postgraduate palliative care training such as a Master of Advanced Studies or postgraduate training. Disagreements were minimal and resolved through discussion.

We organised seven focus groups with 47 healthcare professionals (21 physicians, 26 nurses) from long-term care and hospitals (palliative care unit (PCU), ICU, general internal medicine, and oncology) in German-speaking Switzerland. Participants had on average 20 years (range 3–39) of clinical experience, 10 years (range 0–30) of self-reported palliative care experience, and a mean annual number of 5 (range 1–20) patients continuously deeply sedated until death with the last sedation 5 days to 3 years ago (table 2).

Focus group participants used heterogeneous terminology to describe continuous deep sedation until death. Most physicians and nurses referred to the term “palliative sedation” or “terminal sedation”, but outside specialised palliative care several healthcare professionals used a broader terminology such as “symptom control”, “supportive care”, “comfort therapy” or no specific term at all (table 3).

Table 3 Healthcare professionals' practices of administering sedatives to keep a patient in deep sedation until death.

|

Palliative care specialists

(n = 26) |

Professionals without palliative care specialisation

(n = 21) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Term used | Palliative sedation Terminal sedation Continuous deep sedation |

Palliative sedation Terminal sedation Comfort therapy Supportive care Symptom control No terminology at all |

Comfort therapy Supportive care Symptom control No terminology at all |

| Indication | Patient’s unbearable suffering, given symptoms are refractory | Patient’s unbearable suffering | Patient’s unbearable suffering |

| Intention | Relieving patients suffering by reducing patient’s consciousness | Relieving patients suffering by reducing patient’s consciousness | Intensified alleviation of symptoms taking into account sedation as side-effect |

| Decision-making process | Multi- and interdisciplinary teamwork including patient and family | Multi- and interdisciplinary teamwork including patient and family | Multi- and interdisciplinary teamwork including patient and family |

| Timing | Discussions early in disease trajectory ACP | Discussions early in disease trajectory ACP | Not specifically timed |

| Administration | Dose titration, SC–IV 24-hour monitoring necessary |

Dose titration, SC–IV | Dose titration, SC–IV |

| Sedative agents | Benzodiazepines | Opioids alone or with benzodiazepines | Opioids alone or with benzodiazepines |

ACP = Advance Care Planning; SC = subcutaneous; IV = intravenous. * Specialised palliative care includes all participants with postgraduate palliative care training.

In some institutions, professionals described issues with the term “terminal sedation” as the word “terminal” might indicate an action to terminate someone’s life rather than the disease stage.

“I associate the term ‘terminal sedation’ with something very active, meaning that I intentionally hasten the patient’s death.” (Physician 1, FG5, Hospital)

Physicians and nurses within the same care team used a common terminology, including a shared understanding of the sedation practice. But across institutions, care settings and hospital departments, professionals described difficulty in finding a unique term sufficient for a common understanding.

“I think terminology is used differently between clinical settings and hospital departments such as acute hospital, surgery, or gynaecology. Sometimes terms are not used carefully but if you ask explicitly, it gets obvious what they really mean.” (Nurse 1, FG7, Hospital)

All healthcare professionals agreed that the primary intention of continuous deep sedation until death was to treat a patient’s unbearable suffering. Palliative care specialists consistently described continuous deep sedation until death as an explicitly intended treatment. Outside specialised palliative care, deep sedation was also reported as a side-effect of intensified alleviation of pain.

“Quite often we see [in different hospital departments], that sedation is the effect of intensified symptom control, but not a treatment goal which was explicitly planned in advance.” (Consulting Physician 2, FG7, Palliative Care)

There were further differences regarding the patient’s level of suffering and the restriction to refractory symptoms. Palliative care professionals consistently emphasised the use of continuous deep sedation as an option of last resort and only in case of refractory symptoms.

“It is crucial to differentiate between refractory symptoms and inadequate symptom control.” (Physician 3, FG3, Palliative Care)

Outside specialised palliative care, physicians and nurses also agreed on patients’ unbearable suffering but did not consistently limit sedation to refractory symptoms. Particularly in long-term care, where residents die in very old age, continuous deep sedation was more often described for serious pain, anxiety and existential suffering.

“We have two types of residents eligible for sedation. First, residents who simply do not want to experience the dying process. These residents often wish to be put asleep in order to not perceive death consciously. Second, residents suffering of severe pain who expressed the wish for a sedation.” (Nurse 2, FG2, Long-term care)

Continuous deep sedation in the event of psychological symptoms was discussed as a rare and demanding exception that requires special expertise and discussion. In general, healthcare professionals reported difficulty in separating psychological from physical suffering, because the complexity of a patient’s clinical situation includes both emotional and physical burden.

“In the case of existential suffering, the decision to start sedation is of course difficult. Even if the psychological symptoms are comprehensible, it is easier for us to make a decision in case of massive dyspnoea. Of course, we have to take psychological symptoms seriously but decision-making is much more difficult.” (Nurse 3, FG3, Palliative Care)

Palliative care professionals highlight the importance to discuss the decision with a competent patient early in the disease trajectory in order to inform the patient and get his consent.

“We always get patients’ informed consent in advance. If a patient is not capable of decision-making, sedation with benzodiazepines is not considered as a treatment option.” (Palliative Care Nurse 4, FG2, Long-term care)

Where sedation is not an explicitly intended treatment, but rather a gradual process during increased disease progression, discussions with competent patients are not always possible anymore.

“I think we do not have the characteristic patient population which is eligible for terminal sedation at a specific time. In our tumour patients, this is a gradual development…patients usually are already comatose and not capable anymore to decide whether they really want that or not. In most cases the family members are the ones who have to make the decisions.” (Physician 1, FG5, Hospital)

All healthcare professionals emphasised the importance of multi- and interdisciplinary team sessions. Depending on the care setting, there are different opportunities to call in other professions. In hospitals, particularly university hospitals, healthcare professionals have wide access to other specialties.

In contrast, nursing homes’ multi- and interdisciplinary collaboration is often limited to internal in-patient physicians, external family practitioners and non-medical professions. Where nurses have to deal with several different family practitioners, they often reported difficulties owing to various treatment approaches and palliative care attitudes.

“We have four to five physicians responsible for our residents, each with a different treatment approach. With some physicians, we have to fight for adequate palliation, whereas for others palliative care is taken for granted.” (Nurse 5, FG1, Long-term care)

Independent of the care setting and palliative care specialisation, all physicians and nurses highlighted the importance of involving family members and relatives. As proxy, family members and relatives not only play a role in the decision-making process, they are also part of the unit of care with their own suffering. Some healthcare professionals reported feeling pressured from relatives to start sedation. But all agreed that continuous deep sedation until death is not indicated just because of relatives’ request.

“Palliative sedation is not indicated upon relatives’ request. However, this gives reason to the need for further talks. Because palliative sedation requires consent between patient, relatives, and healthcare professionals, different treatment preferences and goals have to be discussed at a ‘round table’. In my opinion this is a matter of time and communication.” (Physician 4, FG6, Palliative Care)

In line with international guidelines, all palliative care specialists agreed on using benzodiazepines – subcutaneous or intravenous – as medication of first choice to intentionally induce deep sedation. They clearly separate the use of analgesics for symptom control from sedation and therefore, opioids were described as inappropriate.

“We never use opioids as sedative agents. Of course, if necessary, analgesic treatment continues during sedation. Opioids only have sedative effect when overdosed. Therefore, sedation through increased dose titration of opioids is considered inappropriate.” (Physician 5, FG3, Palliative Care)

Other than in emergency situations, continuous deep sedation until death was usually preceded by intermittent sedation with gradual dose titration to a minimum level necessary for palliation. Therefore, re-evaluation and 24-hour monitoring of symptom distress and relief should be provided.

“We constantly monitor the patient and re-evaluate the situation if needed every two hours to check whether he is breathing relaxed and how he reacts when changing his position.” (Palliative Care Nurse 4, FG 2, Long-term care)

Outside specialised palliative care, healthcare professionals described the use of both benzodiazepines and opioid analgesics – subcutaneous or intravenous – to explicitly induce continuous deep sedation until death by gradual dose titration to a minimum level necessary for palliation.

“In our institution, patients are continuously deeply sedated until death through morphine, not benzodiazepines.” (Nurse 6, FG2, Long-term care)

In contrast to palliative care specialists, re-evaluation and 24-hour monitoring was less emphasised by healthcare workers outside specialised palliative care.

“In the terminal stage, it makes no sense to constantly monitor a patient’s blood pressure, heart rate or everything else. Of course, we regularly visit the patient but we also try to get away from too many technical instruments to make the situation more bearable for the family.” (Physician 6, FG5, Hospital)

Furthermore, sedation was described as a gradual process during intensified alleviation of symptoms. In this case, sedation was not explicitly intended but taken into account as side-effect of increased opioid analgesics. Thus, constant monitoring and re-evaluation of the sedation itself was not considered.

“Terminal sedation has not actually been named so far. Sedation is rather part of a gradual process, first we administer morphine, than Haldol and finally Dormicum. We do not plan to start sedation at a specific time e.g., today at 4pm. The use of the term ‘terminal sedation’ just recently developed among palliative care physicians. There are clinical practice guidelines available for everyone on palliative.ch, but in everyday clinical practice it is different.” (Physician 1, FG5, Hospital)

Where continuous deep sedation was well discussed and documented, and consensus was reached between the patient, the family and the healthcare team, moral concerns where not present. In one team, there were moral concerns when administering continuous deep sedation until death for the first time.

“The first time we sedated a patient continuously deeply until death, my team was very concerned about having hastened the patient’s death. We afterwards re-evaluated the situation to differentiate between continuous deep sedation until death and physician assisted death. In contrast to physician assisted death, we do not administer benzodiazepines with the intention to hasten death nor do benzodiazepines hasten death either. It’s very important to take moral concerns seriously and discuss them adequately.” (Palliative Care Nurse 7, FG1, Long-term Care)

The more healthcare professionals struggled with justifying the sedation practice, the higher the risk of experiencing moral concerns. Our findings revealed that this appeared to be in part a function of lack of proper decision-making to reach a consensus within the team, as well as with patients and family (e.g., lack of time in emergency case).

“We always try to document and discuss palliative sedation sufficiently in order to reach a consensus with the patient, the family and within the healthcare team. But in emergency situations you have to act immediately. Retrospectively you might see things more clearly and maybe you would have done things differently.” (Consulting Physician 2, FG7, Palliative Care)

Our study reveals that healthcare professionals with and without palliative care specialisation have a different understanding of “continuous deep sedation until death”. Palliative care specialists defined continuous deep sedation until death most restrictively as the explicitly intended use of benzodiazepines in order to treat refractory symptoms as an option of last resort. Outside specialised palliative care, healthcare professionals put less emphasis on refractory symptoms and not only described sedation as an explicitly intended treatment but also as a side-effect taken into account with intensified alleviation of symptoms.

In line with previous studies we found a lack of consistent terminology and definitions [19]. While palliative care specialists consistently used “palliative”, “terminal”, or “continuous deep sedation”, outside specialised palliative care, sedation was sometimes described more generally as “symptom control” or “comfort therapy”. Papavasiliou and colleagues revealed that the heterogeneity in definitions seems to be caused by differences in language and vocabulary used by healthcare professionals of different care settings [20]. But even when a common term was used, healthcare professionals did not necessarily describe the same understanding of the sedation practice. The fact that nurses felt they had to push physicians for appropriate palliation, might be the result of a breakdown in communication where the same term, and what constitutes appropriate sedation practices, mean different things to different professions. Thus, in certain settings patients might be at risk of getting insufficient relief from their suffering. Therefore, it seems that a universally agreed term is not sufficient for a common understanding.

Beside the heterogeneous terminology, our results highlight the problematic field of indication. For palliative care specialists, continuous deep sedation is only indicated when a symptom is refractory. But, whether a symptom is regarded as refractory differs according to healthcare professionals’ clinical experience and available resources. Regardless of professionals’ palliative care specialisation, all healthcare professionals emphasise that a patient’s unbearable suffering indicates a need for palliative sedation. In clinical practice, it can be unclear what “unbearable suffering” entails and to what extent physical and psychological suffering is relevant. According to Bozzaro and colleagues, the problem originates in the definition of suffering itself [21]. Suffering is defined as individual and subjective patient’s perception, which contrasts with the fact that physicians are the ones who diagnose it [22]. Previous studies revealed that this seems even more challenging in case of existential suffering [23, 24].

In clinical practice, medical decision-making for continuous deep sedation is not only based on clinical indications but also influenced by the social context, including patients’ and healthcare professionals’ intentions and views [25]. According to clinical practice guidelines, continuous deep sedation until death is only indicated with the intention to induce a state of decreased or absent awareness in order to relieve a patient’s unbearable suffering and refractory symptoms [12]. Previous findings reveal that compliance with clinical practice guidelines seems better in the case of palliative care expertise or when a consulting expert was called in [26]. Our findings revealed that palliative care clinicians have a more restrictive understanding of palliative sedation and clearly exclude unintended sedation [27]. In contrast, outside specialised palliative care, sedation was not always intended, but rather taken into account as a side effect of increased pain medication in terminally ill patients. As a consequence, outside specialised palliative care, opioids were sometimes used as sole agent to induce sedation [28]. This indicates that some healthcare professionals might subsume the sedation practice under possibly life-shortening end-of-life decisions, such as intensified alleviation of pain and symptoms, instead of viewed as a separate practice. In line with these findings healthcare professionals less experienced in palliative care tend to have ambiguous attitudes towards continuous deep sedation and are more likely consider it as possibly life shortening [29–31]. Current evidence does not suggest that practicing continuous deep sedation until death is generally emotionally burdensome. But the more healthcare professionals struggle with justifying the sedation practice, the higher their risk of experiencing emotional distress [24]. Our findings revealed that this appeared to be in part a function of proper decision-making to reach a consensus within the team, as well as with patients and family (e.g., lack of time in emergency case)

The variation in sedation understanding and practice is furthermore related to setting-specific structural and personnel resources. Results from Belgium revealed that the considerable variation in administration and monitoring between family practitioners and medical specialists was most likely affected by the different resources provided by the respective clinical care setting [32]. Most of the interviewed palliative care specialists worked in palliative care units and thus reported frequent multidisciplinary exchange with experts of other hospital departments, constant patient monitoring and continuous administration of benzodiazepines through intravenous infusion. In primary care and internal medicine, professionals often reported limited options for multidisciplinary exchange, and difficulty in ensuring overnight monitoring, intravenous infusions and access to sedative medication. This lack of resources might partly account for the variation observed [28].

Our study indicates that medical decision-making for continuous deep sedation goes beyond a conceptual definition or clinical indications. For future studies, the question remains to what extent a definition can be reduced to objective parts without losing the purpose of providing information on good clinical practice. Therefore, the best conceptual definition might not reflect the best clinical practice in its fullest.

Adherence to guidelines on continuous deep sedation outside specialised palliative care remains modest. This might be caused by a lack of shared knowledge or because the implementation of current practice guidelines is not feasible. Knowledge transfer could be improved by increased multidisciplinary networking, the preferred approach for patient-centred care, and timely involvement of palliative care consultants in order to encourage the early recognition of palliative care needs. This might facilitate the coordination of care at a patient’s end of life and thus enable a mutually developed consensus for defining and understanding the distinct sedation practices. For long-term care facilities, the presence of a physician experienced in geriatric palliative care working closely together with the nursing team is crucial. Therefore, training and earlier involvement of expert consultation teams in general internal medicine and nursing homes is of high importance. Also, mobile palliative care consultant teams seem promising as they are not only supportive for primary care physicians in long-term care and home care, but also aim to reduce the number of emergency hospitalisations. But despite an increasing need, there is only a limited number of mobile palliative care teams, and reimbursement is often not sufficient, at least in Switzerland. Therefore, policy makers should focus on providing financial and regulatory support for the implementation of palliative care services to provide resources required for appropriate palliative sedation across all care settings.

Our results do not allow any conclusions about family practitioners’ experience since we were unable to recruit respondents. Possible reasons for the absence of family practitioners might be lack of sedation experience, time constraints or not recognising our study invitation in the newsletter. For anonymity reasons, we were not able to recruit family practitioners personally and therefore had to reach them via the newsletter of the Swiss association of general practitioners. Future studies are needed to investigate family practitioners’ experience with the administration of sedative substances to keep a patient in deep sedation until death. Another limitation is potential recall bias since some healthcare professionals’ involvement in sedation practice varied considerably and sometimes occurred up to three years before this study.

We found that the understanding of “continuous deep sedation until death” varied considerably between healthcare settings and palliative care specialisation. In order to move forward, early involvement of palliative care experts, sedation training, as well as financial and regulatory support should be provided to encourage multidisciplinary collaboration and a common sedation understanding between palliative care experts and physicians and nurses who practice continuous deep sedation until death also outside specialised palliative care.

We thank all the physicians and nurses who participated in the study.

The author) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (research grant 406740-139309, National Research Program 67 “End of Life”).

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

1 Swart SJ , van der Heide A , van Zuylen L , Perez RSGM , Zuurmond WWA , van der Maas PJ , et al. Considerations of physicians about the depth of palliative sedation at the end of life. CMAJ. 2012;184(7):E360–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.110847

2 Miccinesi G , Rietjens JAC , Deliens L , Paci E , Bosshard G , Nilstun T , et al.; EURELD Consortium. Continuous deep sedation: physicians’ experiences in six European countries. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31(2):122–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.07.004

3 Putman MS , Yoon JD , Rasinski KA , Curlin FA . Intentional sedation to unconsciousness at the end of life: findings from a national physician survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):326–34. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.007

4 Seale C . Continuous deep sedation in medical practice: a descriptive study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(1):44–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.06.007

5 Robijn L , Cohen J , Rietjens J , Deliens L , Chambaere K . Trends in Continuous Deep Sedation until Death between 2007 and 2013: A Repeated Nationwide Survey. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0158188. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0158188

6 Chao YS , Boivin A , Marcoux I , Garnon G , Mays N , Lehoux P , et al.; Advisory Committee; Canadian Medical Association; College of Family Physicians of Canada; Canadian Bar Association; Ministère de la santé et des services sociaux du Québec; Réseau des soins palliatifs du Québec; Commissaire à la santé et au bien-être du Québec. International changes in end-of-life practices over time: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(1):539. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1749-z

7 Bosshard G , Zellweger U , Bopp M , Schmid M , Hurst SA , Puhan MA , et al. Medical end-of-Life practices in Switzerland: A comparison of 2001 and 2013. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):555–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.7676

8 van der Heide A , van Delden JJM , Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD . End-of-Life Decisions in the Netherlands over 25 Years. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):492–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1705630

9 Hurst SA , Zellweger U , Bosshard G , Bopp M ; Swiss Medical End-of-Life Decisions Study Group. Medical end-of-life practices in Swiss cultural regions: a death certificate study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):54. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1043-5

10 Papavasiliou ES , Brearley SG , Seymour JE , Brown J , Payne SA . Papavasiliou ES, Brearley SG, Seymour JE, Brown J, Payne SA, on behalf of EUROIMPACT. From sedation to continuous sedation until death: how has the conceptual basis of sedation in end-of-life care changed over time? J Pain Symptom Manage 2013; 5:706-723. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(2):370. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.12.227

11 Abarshi E , Rietjens J , Robijn L , Caraceni A , Payne S , Deliens L , et al.; EURO IMPACT. International variations in clinical practice guidelines for palliative sedation: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2017;7(3):223–9.

12 Cherny NI , Radbruch L ; Board of the European Association for Palliative Care. European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) recommended framework for the use of sedation in palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):581–93. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216309107024

13 Schildmann EK , Schildmann J , Kiesewetter I . Medication and monitoring in palliative sedation therapy: a systematic review and quality assessment of published guidelines. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2015;49(4):734–46. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.08.013

14 Hedinger D , Braun J , Zellweger U , Kaplan V , Bopp M ; Swiss National Cohort Study Group. Moving to and dying in a nursing home depends not only on health - an analysis of socio-demographic determinants of place of death in Switzerland. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e113236. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0113236

15 Rietjens J , van Delden J , Onwuteaka-Philipsen B , Buiting H , van der Maas P , van der Heide A . Continuous deep sedation for patients nearing death in the Netherlands: descriptive study. BMJ. 2008;336(7648):810–3. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39504.531505.25

16 McCormack R , Clifford M , Conroy M . Attitudes of UK doctors towards euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide: a systematic literature review [Erratum]. Palliat Med. 2012;26(1):23–33. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216310397688

17 Foley R-A , Johnston WS , Bernard M , Canevascini M , Currat T , Borasio GD , et al. Attitudes Regarding Palliative Sedation and Death Hastening Among Swiss Physicians: A Contextually Sensitive Approach. Death Stud. 2015;39(8):473–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2015.1029142

18 Tong A , Sainsbury P , Craig J . Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

19 Schildmann E , Schildmann J . Palliative sedation therapy: a systematic literature review and critical appraisal of available guidance on indication and decision making. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(5):601–11. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2013.0511

20 Papavasiliou ES , Brearley SG , Seymour JE , Brown J , Payne SA ; EURO IMPACT. From sedation to continuous sedation until death: how has the conceptual basis of sedation in end-of-life care changed over time? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(5):691–706. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.11.008

21 Bozzaro C . Der Leidensbegriff im medizinischen Kontext: Ein Problemaufriss am Beispiel der tiefen palliativen Sedierung am Lebensende [The concept of suffering in medicine: an investigation using the example of deep palliative sedation at the end of life]. Ethik Med. 2015;27(2):93–106. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00481-015-0339-7

22 Müller-Busch HC , Radbruch L , Strasser F , Voltz R . Empfehlungen zur palliativen Sedierung [Definitions and recommendations for palliative sedation]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2006;131(48):2733–6. Article in German.

23 Bakogiannis A , Papavasiliou EE . Language Barriers to Defining Concepts in Medicine: The Case of Palliative Sedation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2016;33(9):909–10. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909115586186

24 Ziegler S , Merker H , Schmid M , Puhan MA . The impact of the inpatient practice of continuous deep sedation until death on healthcare professionals’ emotional well-being: a systematic review. BMC Palliat Care. 2017;16(1):30. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0205-0

25 Robijn L , Chambaere K , Raus K , Rietjens J , Deliens L . Reasons for continuous sedation until death in cancer patients: a qualitative interview study. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26(1):e12405. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12405

26 Hasselaar JGJ , Reuzel RPB , Verhagen SCAHHVM , de Graeff A , Vissers KC , Crul BJP . Improving prescription in palliative sedation: compliance with dutch guidelines. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1166–71. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.11.1166

27 Maiser S , Estrada-Stephen K , Sahr N , Gully J , Marks S . A Survey of Hospice and Palliative Care Clinicians’ Experiences and Attitudes Regarding the Use of Palliative Sedation. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(9):915–21. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0464

28 Papavasiliou EE , Chambaere K , Deliens L , Brearley S , Payne S , Rietjens J , et al.; on behalf of EURO IMPACT. Physician-reported practices on continuous deep sedation until death: A descriptive and comparative study. Palliat Med. 2014;28(6):491–500. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216314530768

29 Foley R-A , Johnston WS , Bernard M , Canevascini M , Currat T , Borasio GD , et al. Attitudes Regarding Palliative Sedation and Death Hastening Among Swiss Physicians: A Contextually Sensitive Approach. Death Stud. 2015;39(8):473–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2015.1029142

30 Inghelbrecht E , Bilsen J , Mortier F , Deliens L . Nurses’ attitudes towards end-of-life decisions in medical practice: a nationwide study in Flanders, Belgium. Palliat Med. 2009;23(7):649–58. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216309106810

31 Inghelbrecht E , Bilsen J , Mortier F , Deliens L . Continuous deep sedation until death in Belgium: a survey among nurses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(5):870–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.07.022

32 Putman MS , Yoon JD , Rasinski KA , Curlin FA . Intentional sedation to unconsciousness at the end of life: findings from a national physician survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):326–34. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.09.007

SZ designed the research question, organised the focus groups, performed the data analysis, and drafted the first and final version of the manuscript. MS contributed substantially to the study design, the carrying out of the focus groups, the data analysis, the interpretation of the results and critically revised the manuscript. MB, GB, and MAP substantially contributed to the design of the study, the interpretation of the results, and critically revised the manuscript. MAP gave final approval to submission. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The author) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (research grant 406740-139309, National Research Program 67 “End of Life”).

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.