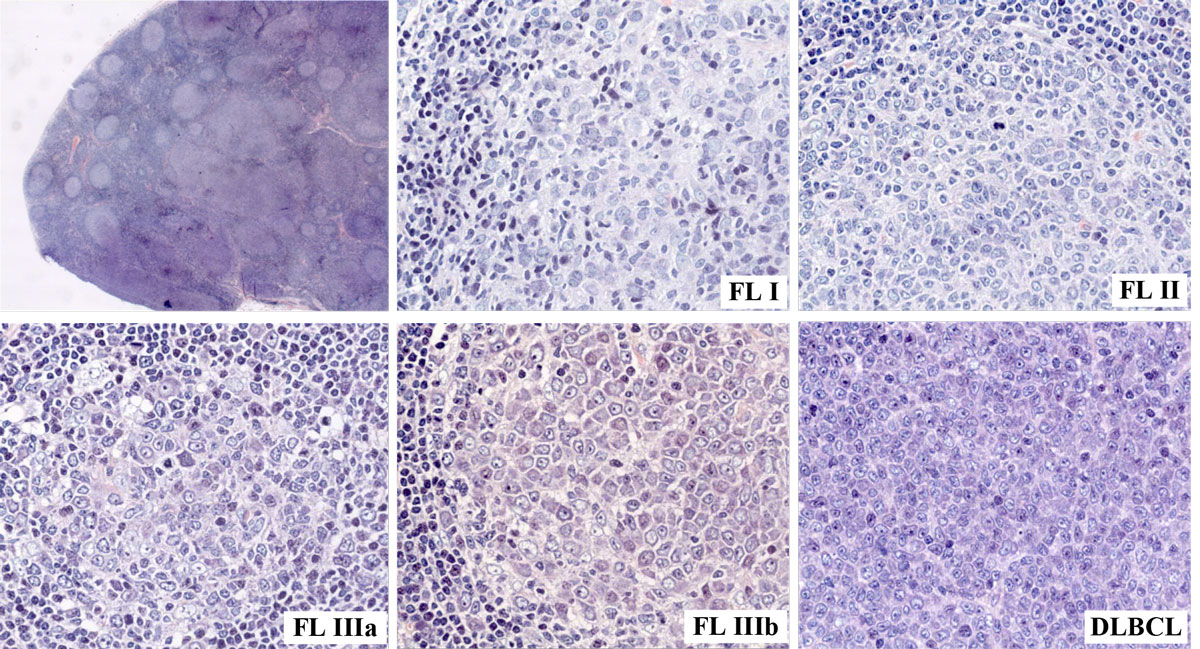

Figure 1 Enlarged cervical lymph node (4 cm in diameter) of a 64-year-old male patient harbouring follicular lymphoma (FL) of varying histological grades, including transformation into a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14635

British National Lymphoma Investigation

bendamustine-rituximab

confidence interval

computed tomography

cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone

diffuse large B cell lymphoma

European Society for Medical Oncology

fluorescence-activated cell sorting

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose

fluorescence in situ hybridisation

Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index

obinutuzumab plus bendamustine

obinutuzumab plus cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), Oncovin (vincristine), and prednisone

obinutuzumab plus fludarabine/cyclophosphamide

hepatitis B virus

hepatitis C virus

high-power field

non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

hazard ratio

positron emission tomography

polymerase chain reaction

rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin (doxorubicin), Oncovin (vincristine) and prednisone

rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone

rituximab-fludarabine plus mitoxantrone

Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research

the German Study Group Indolent Lymphoma

World Health Organization

Histogenetically, follicular lymphoma arises from germinal centre B cells. As a low-grade tumour, it is the most commonly occurring subtype among indolent B cell lymphomas in the Western world [1, 2]. Follicular lymphoma is characterised by a relapsing and remitting disease course that may undergo transition to a more aggressive disease. In the past few years, new treatment regimens have made an impact on the management of follicular lymphoma, resulting in more favourable clinical outcomes. The median overall survival has improved dramatically and can now reach 10 to 12 years or more [3, 4]. Immunochemotherapy is currently the standard of care for patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma in need of treatment [5]. Chemotherapy-free treatment with anti-CD20 antibodies (such as rituximab) is an option for those with a low disease burden. Nevertheless, the majority of patients will experience relapse and require several lines of therapy. There is still the need for effective regimens that achieve disease control with minimal treatment-related toxicity.

This review follows our 2011 publication on the treatment and management of follicular lymphoma [6] and represents an update on the key issues encountered in clinical practice from a Swiss perspective.

Histologically, follicular lymphoma is diagnosed according to the criteria of the 4th World Health Organization (WHO) classification issued in 2008 and updated in 2017 [7, 8]. Follicular lymphoma is defined as a neoplasm composed of germinal centre B cells, namely centroblasts and centrocytes, exhibiting, in most cases at least, a partly follicular growth pattern [8] (fig. 1). Grading of follicular lymphoma is mandatory and is based on the count of centroblasts per high-power field (HPF); in general, tumours with more numerous centroblasts show more aggressive clinical behaviour [8]. Grade 1 (0–5 centroblasts per HPF) and grade 2 (6–15 centroblasts per HPF) tumours with similar clinical characteristics are considered to be of low grade. Grade 3 tumours are considered to be high-grade, and are further divided into 3a and 3b neoplasms; both exhibit >15 centroblasts per HPF but confluent sheets and strands of centroblasts are present in grade 3b neoplasms [9]. Although still under debate, grade 3b follicular lymphoma may be biologically distinct from other follicular lymphomas, with a more aggressive course and with varying molecular and genetic features (table 1) [11], including the absence of the t(14;18)(q32;q21) chromosomal translocation, down-regulation of CD10 protein and overexpression of mutated melanoma-associated antigen 1 (MUM-1) protein [12]. Another issue is how to interpret a coexisting tumour component of diffuse large B cell lymphoma (DLBCL) next to follicular lymphoma of any grade of malignancy, recognised by the valid WHO classification as an additional second tumour [10]. This point is key for distinguishing between de novo DLBCL and transformation of initial follicular lymphoma, which occurs in approximately 30 to 40% of follicular lymphoma patients [13]. For the clinician, the distinction between grade 3a and 3b follicular lymphoma is crucial and determines prognosis and therapeutic strategy. Clinically, most patients initially present with asymptomatic peripheral lymphadenopathy, affecting the cervical, axillary, femoral and inguinal regions [14, 15]. Although lymph nodes are most commonly primarily involved, the disease may also originate at extranodal sites. The WHO in particular recognises (1) in situ follicular neoplasia, (2) duodenal-type follicular lymphoma, (3) testicular follicular lymphoma and (4) diffuse follicular lymphoma as four distinct variants, and furthermore classifies cutaneous follicle centre lymphomas and paediatric-type follicular lymphoma as two separate entities [8].

Figure 1 Enlarged cervical lymph node (4 cm in diameter) of a 64-year-old male patient harbouring follicular lymphoma (FL) of varying histological grades, including transformation into a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL).

Table 1 Features that distinguish grade 3b follicular lymphoma from grades 1–3a [9, 10].

| Grades 1–3a | Grade 3b | |

|---|---|---|

| WHO grading scheme | Grades 1–2 ≤15 centroblasts per high-power field*

Grade 3a >15 centroblasts per high-power field |

>15 centroblasts per high-power field Presence of solid sheets of centroblasts |

| Genotype | t(14;18)(q32;q21); BCL2-IGH in 90% of cases |

t(14;18)(q32;q21); BCL2-IGH in 50% of cases t(3;14)(q27;q32);BCL6-IGH in 10% of cases |

| Immunohistochemistry | Expression of CD10 | Down-regulation of CD10 Expression of MUM1 |

| Clinical behaviour | Indolent | Aggressive, resembling DLBCL |

DLBCL = diffuse large B cell lymphoma; MUM-1 = mutated melanoma-associated antigen; WHO = world Health Organization * high-power field defined as 0.159 mm2

The 2016 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) guidelines provide a summary for the diagnosis of follicular lymphoma [5]. The majority of follicular lymphomas are diagnosed by bioptic lymph node examination; fine-needle aspiration does not provide adequate material for tumour grading. The same is true for trephine biopsies that have to be performed for staging purposes, as follicular lymphoma involves bone marrow in about 60 to 70% of patients [16]. For the definition of bulky disease, which has varied over time, we propose a cut-off of >7 cm diameter, in keeping with the ESMO guidelines [5]. The biological heterogeneity and disseminated presentation of follicular lymphoma makes it difficult to select a site for biopsy. The factors that should be taken into account when choosing a biopsy site are accessibility for surgical removal and the diagnostic relevance. A selection based purely on size of the lymph node should be avoided, owing to the possibility of necrosis within large lymph nodes.

In Switzerland, a common practice is to use contrast-enhanced positron emission tomography / computed tomography (PET-CT) to identify the most suitable lymph node for biopsy [17]. Although PET-CT is not yet routinely used for staging at diagnosis, it has been shown that follicular lymphoma is avid for 18F-FDG (18F-fluorodeoxyglucose) and that over 90% of patients are PET-CT positive at initial presentation [18]. For patients with early stage follicular lymphoma who are scheduled for localised radiation, PET-CT can be used to map out the area for involved-field radiation therapy and also to exclude the presence of distal sites of disease [19]. The latest ESMO guidelines state that fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis is an optional procedure for diagnostic work-up [5]; we suggest that if access to FACS is available, FACS analysis on bone marrow aspirates should be done to judge on bone marrow involvement [20]. Of note, trephine biopsy plus immunohistochemistry may be more sensitive than bone marrow aspirates plus FACS to detect bone marrow involvement in follicular lymphoma [21].

The use of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for detecting B cell clonality in follicular lymphoma is associated with a high rate of false negatives, due to ongoing somatic immunoglobulin variable region heavy chain (IgVH) hypermutations [22]. In addition to morphological and immunohistochemical studies, fluorescence in situ hybridisation (FISH) is the preferred method to detect the t(14;18)(q32;q21) chromosomal translocation, which is most specifically found in follicular lymphoma [23, 24]. FISH analysis may have a great differential diagnostic impact, separating follicular lymphoma from reactive follicular hyperplasia and from lymphomas other than follicular lymphoma.

Routine testing for hepatitis B surface antigen and hepatitis B core antibody at baseline and before therapy is strongly recommended for all patients who will undergo immunosuppressive therapy, to mitigate the risk of hepatitis B virus (HBV) reactivation [25]. If positive, viral load assessment by measuring HBV DNA should be performed and anti-viral treatment initiated. HBV vaccination may be considered for patients who are HBV-negative and not in immediate need of treatment.

The Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (FLIPI) [26] is routinely used as a general prognostic tool. The FLIPI was developed before the rituximab era. The five main prognostic factors are the number of nodal sites (≤ or >4), lactate dehydrogenase (normal vs elevated), age (≤ or >60 years), stage (I, II vs III, IV), and haemoglobin (normal vs <120 g/L). The FLIPI-2 includes age >60 years, elevated β2-microglobulin levels, haemoglobin <120 g/l, bone marrow involvement, and lymph node diameter >6 cm as independent risk factors for progression-free survival in the era of rituximab chemotherapy. The FLIPI-2 so far has not gained acceptance and is still investigational. The recent m7-FLIPI index integrates the mutation status of seven clinically relevant genes together with the FLIPI and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, in order to identify the subset of follicular lymphoma patients who are at greatest risk of treatment failure [27]. None of these scoring indexes provide guidance on when to initiate therapy.

The trigger point for starting treatment remains a difficult question. A key driver for beginning treatment is the presence of symptomatic disease. The criteria outlined by the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) for starting treatment includes the presence of at least one of the following: B symptoms; symptomatically enlarged lymph nodes or spleen; clinically significant progression of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly or other follicular lymphoma lesions; involvement of at least three nodal sites larger than 3 cm, presence of bulky disease, haemoglobin <100 g/l, and platelets <100 × 109/l [28]. According to the British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI), bone lesions may also be regarded as a trigger for initiating treatment. The SAKK criteria for initiating treatment are summarised in table 2, alongside the criteria for the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires and the BNLI groups for comparison. Symptomatic bone marrow involvement is also a criterion for beginning treatment. However, the decision to start treatment often has to be individualised and is reached upon mutual agreement between the patient and clinician.

Table 2 Comparison of criteria for starting treatment in follicular lymphoma patients.

| Group | Criteria |

|---|---|

| Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK) [28] | • Presence of B symptoms • Symptomatic enlarged lymph nodes or spleen • Clinically significant progression of lymphadenopathy, splenomegaly or other FL lesions (50% increase in size over a period of at least 6 months) • At least 3 nodal sites involved (>3 cm) • Presence of bulky disease (>7 cm) • Haemoglobin level <100 g/l • Platelet level <100 × 109/l (due to bone marrow infiltration or splenomegaly) |

| British National Lymphoma Investigation (BNLI) [29] | • Presence of pruritus or B symptoms • Rapid disease progression during the past 3 months • Life-threatening organ involvement • Significant bone marrow infiltration resulting in bone marrow depression (defined as a haemoglobin level <100 g/l, white cell count <3.0 × 109/l, or platelet count <100 × 109/l in the absence of other causes) • Localised bone lesions • Renal infiltration • Macroscopic liver involvement |

| Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) [30] | • Largest nodal (or extranodal) size >7 cm • At least 3 nodal sites of >3 cm • Presence of systemic symptoms • Presence of serous effusion • Substantial enlargement of the spleen • Risk of vital organ compression • Presence of leukaemia or blood cytopenias |

Around 10% of low-grade follicular lymphomas are diagnosed in early stage I or II [31]. Radiation therapy is the treatment of choice for these patients, with the possibility of long-lasting remissions and curative potential [32]. The treatment volume has evolved over the past decades from the earlier extended-field to involved-field and, more recently, to involved-site radiotherapy. Involved-site radiotherapy treats the affected nodes with a clinical target volume margin of a few centimetres. The reduced toxicity linked to involved-site radiotherapy comes at the cost of a potentially higher recurrence rate in untreated adjacent areas. Nowadays, primary radiation therapy is given at a dose of 24 Gy, which is significantly lower than the doses delivered in the past (30–40 Gy). This development is the result of a randomised trial comparing 24 Gy to 40 Gy in indolent lymphomas, demonstrating similar efficacy with both doses [33]. Reports from patient cohorts that were treated with low-dose radiotherapy of 2 × 2 Gy, mostly for palliation of advanced disease, showed promising results [34, 35]. Therefore, a randomised trial was carried out to compare 2 × 2 Gy with the standard dose of 24 Gy in follicular lymphoma [36]. Preliminary results demonstrated a significantly higher rate of progression in the low-dose group, so the 4 Gy dose should not be adopted for treatment with curative intent. Importantly, toxicity in the 24 Gy group was low, with <3% grade III acute reactions, demonstrating the safety of modern schedules of radiation therapy with limited treatment volumes and radiation doses. However, the preferred 24 Gy dose is not accepted by all groups and some use a minimum of 30 Gy [37].

It should be noted that most of the relapses in patients with early-stage follicular lymphoma occur outside the irradiated fields [38]. Indeed, an important finding from the LymphomaCare study was that rigorously staged patients had superior progression-free survival compared with patients who had not undergone a rigorous staging process [31]. In a retrospective study conducted in 310 patients with localised follicular lymphoma, excellent outcomes were obtained after radiotherapy in patients who were PET-CT staged (5-year overall survival: 95.8%) [39]. This reiterates the importance of accurate staging using PET-CT prior to radiation therapy, in order to define the areas to be irradiated and to rule out occult disease [38, 40].

Besides radiotherapy alone, the combination with rituximab for early stage follicular lymphoma has been tested in the MIR trial [41, 42]. Preliminary data show an excellent progression-free survival of almost 80% at 5 years after treatment [42]. A comparison of various first-line treatment strategies in 471 patients with stage I follicular lymphoma who participated in the LymphomaCare study showed that the different approaches resulted in similar outcomes [31]. Recent data from a randomised controlled trial in 150 patients with stage I–II follicular lymphoma indicated that treatment with six cycles of CVP (cyclophosphamide, vincristine and prednisone) or rituximab‐CVP after involved-field radiotherapy significantly improved progression-free survival compared with radiotherapy alone (10-year progression-free survival 58 vs 41%, respectively) [43]. This suggests that systemic therapy may prevent progression outside of the radiation fields. However, it is not yet clear if the combination of radiotherapy plus rituximab-based systemic therapy will become standard of care in the future.

Watchful waiting remains an acceptable approach in selected patients in the rituximab era, with no detrimental effects on overall survival [44–46]. However, better indices are needed to identify patients who may benefit from early intervention. There is also no conclusive data on whether watchful waiting affects the incidence of transformation of follicular lymphoma. For elderly patients and those with poor performance status, watchful waiting can be considered in selected cases [47].

For patients with symptomatic stage I–II disease without the option to undergo radiotherapy and those with advanced disease (stage III–IV), the treatment approach is similar. Current standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced follicular lymphoma consists of immunochemotherapy with the anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody rituximab (MabThera®/Rituxan®) in combination with a chemotherapy component [5]. Although the ESMO guidelines place equal emphasis on the use of bendamustine and CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone), bendamustine has increasingly been used combined with rituximab [15]. A randomised, multicentre phase III trial by the Study group Indolent Lymphoma (StiL) compared rituximab-CHOP (R-CHOP) with bendamustine-rituximab in 549 treatment-naïve patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphoma. In the subgroup of patients with follicular lymphoma, median progression-free survival was significantly better in the bendamustine-rituximab group compared with R-CHOP (median progression-free survival not reached vs 40.9 months; p = 0.007). Furthermore, the bendamustine-rituximab regimen had fewer adverse effects [48]. Results from the BRIGHT study indicated that bendamustine-rituximab was non-inferior to R-CHOP or R-CVP in terms of complete response (31 vs 25%, respectively; p = 0.0225) and overall response (97 and 91%, respectively; p = 0.0102) in 447 patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) or mantle cell lymphoma [49]. The safety findings of the BRIGHT study differed from the StiL study in that bendamustine-rituximab was found to have a distinct safety profile compared with R-CHOP or R-CVP, but the overall tolerability of the bendamustine-rituximab regimen was favourable in this clinical setting [49]. A recent 5-year update of the BRIGHT study identified a higher risk of secondary cancers (mainly skin cancers) in the bendamustine-rituximab arm and it was speculated that this could have been due to rituximab maintenance (which was used in 43% of the patients) [50]. It should be kept in mind that there is less long-term follow-up data for bendamustine-rituximab compared with R-CHOP; this is especially relevant when weighing the treatment options for younger patients.

Although the findings from the StiL and BRIGHT studies point towards bendamustine-rituximab as the treatment of choice for follicular lymphoma patients with grade 1 and 2 disease, the optimal treatment for patients with grade 3a disease remains unclear: these patients were not included in either study. The FOLLO5 trial assessed R-CHOP, R-CVP and rituximab, fludarabine and mitoxantrone (R-FM) as front-line treatment in 534 patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma [51]. The overall response rates were 88, 93 and 91% for R-CVP, R-CHOP and R-FM, respectively (p = 0.247). The 3-year progression-free survival rates were 52, 68 and 63% (p = 0.011), respectively, and 3-year overall survival was 95% for the whole series. The authors concluded that R-CHOP and R-FM were superior to R-CVP in terms of 3-year time to treatment failure and progression-free survival, but R-CHOP had a more favourable risk-benefit profile [51]. These findings were recently confirmed, with 8-year progression-free survival rates of 57 and 59% for R-CHOP and R-FM, compared with 46% for R-CVP [52].

In Switzerland, bendamustine-rituximab is widely used as a front-line treatment option in patients with grade 3a follicular lymphoma, although R-CHOP is also used in Switzerland [53]. Many clinicians regard R-CHOP as overtreatment for low-grade follicular lymphoma, but whether grade 3a is considered high- or low-grade disease is still a matter of debate [54]. The results from the StiL and BRIGHT trials, alongside the findings of several other studies with bendamustine-rituximab [55, 56], indicate that the bendamustine-rituximab combination may be preferable to R-CHOP or R-CVP for the front-line treatment of follicular lymphoma patients with low-grade disease who need therapy. The findings from the FOLLO5 study indicate that R-CHOP still holds a place in the first-line treatment of patients with high-risk characteristics, including those with evidence of bone marrow involvement and high levels of β2-microglobulin [57].

For patients who are in need of treatment but who may not be able to tolerate chemotherapy, or for those with a low disease burden, rituximab monotherapy provides a safe and effective first-line treatment option, with the potential for lasting molecular responses [58, 59]. The SAKK tested rituximab monotherapy in chemotherapy-naïve and pretreated follicular lymphoma patients, resulting in overall response rates of 67 and 46%, respectively [60]. Data from the SAKK 35/98 trial indicated that the independent factors predictive of response to treatment with single-agent rituximab were: low disease bulk (<5 cm), follicular histology, normal haemoglobin levels and low lymphocyte counts [61]. At long-term follow-up, 35% of patients did not show disease progression after 8 years [28]. This number was 45% in the subgroup of previously untreated patients who responded to rituximab induction and who were given prolonged rituximab maintenance [28]. Despite the fact that single-agent rituximab is widely accepted both in Switzerland and internationally [28], and is recommended in the latest ESMO guidelines [5], rituximab monotherapy is still not on the Swiss Specialties List and this is considered off-label use in Switzerland. Within the SAKK, the aim is to develop further regimens using anti-CD20 antibodies as a backbone, in combination with new molecules such as immunomodulatory drugs (e.g., lenalidomide; SAKK 35/10 trial), or Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitors (ibrutinib; SAKK 35/14 trial), as well as the BCL-2 inhibitor venetoclax (SAKK 35/15 trial). Further details on the ongoing SAKK trials can be found on www.sakk.ch/en/sakk-provides/our-trials/. The combination of lenalidomide with rituximab (also known as R2) has shown good potential for the treatment of indolent lymphomas, including follicular lymphoma [62]. In previously untreated patients with indolent NHL, lenalidomide-rituximab treatment showed good overall response rates (75–96%) and complete response or unconfirmed complete response rates between 36 and 71% [63]. However, a recent phase III trial (RELEVANCE) did not show improved complete response / unconfirmed complete response or progression-free survival when comparing lenalidomide-rituximab with standard-of-care rituximab plus chemotherapy in previously untreated follicular lymphoma patients [64]. Other groups are studying rituximab-ibrutinib in the front-line setting [65].

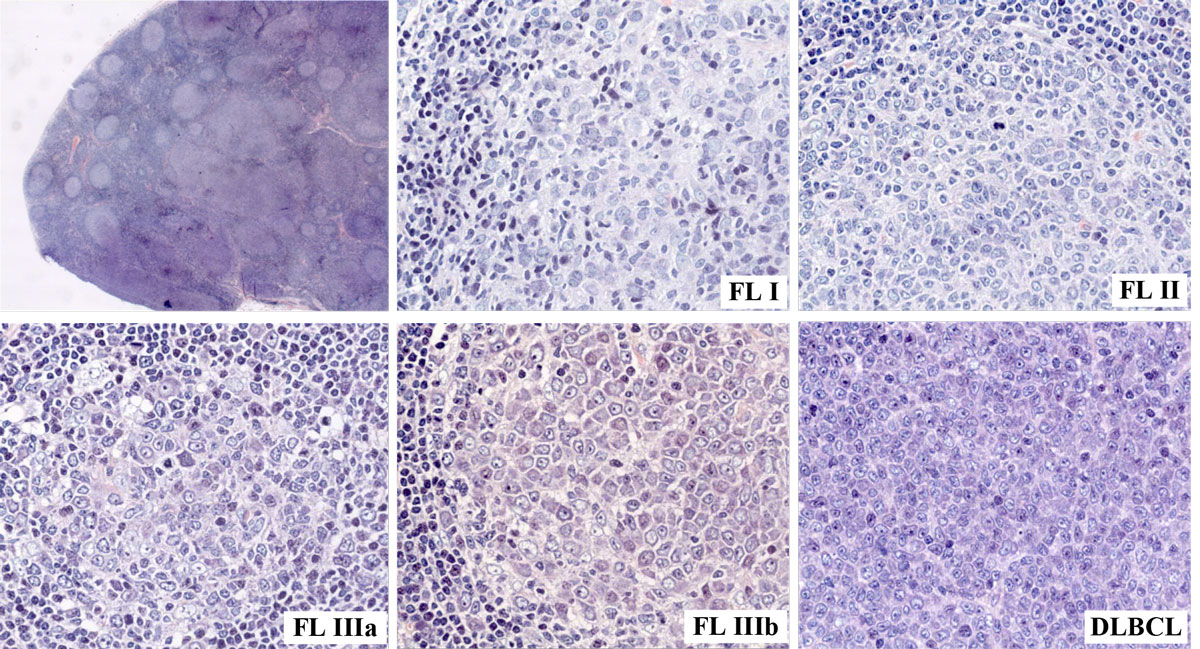

Recently, Swiss regulatory authorities have approved an alternative anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody (obinutuzumab, Gazyvaro®) plus chemotherapy followed by obinutuzumab maintenance for first-line follicular lymphoma patients. The GALLIUM study compared the efficacy and safety of obinutuzumab-based with rituximab-based front-line regimens head-to-head in 1202 treatment-naïve follicular lymphoma patients with grade 1-3a disease [66]. Responders received either obinutuzumab or rituximab maintenance. Results from pre-planned interim analyses showed that obinutuzumab-based regimens resulted in better progression-free survival. After a median follow-up of 34.5 months, there was a 34% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death with obinutuzumab-based induction regimens and maintenance. Three-year progression-free survival rates in the obinutuzumab and rituximab arms were 80 and 73.3%, respectively (hazard ratio [HR] 0.66, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.51–0.85; p = 0.001); overall survival rates were similar in both arms. Unexpectedly, there was a higher incidence of toxicities in patients on bendamustine in both arms, notably infections and second neoplasms [66]. Although the study demonstrated a progression-free survival advantage with the use of obinutuzumab, the higher level of toxicity in the bendamustine arms needs to be better understood before these treatment regimens can be routinely used in the front-line setting. A summary of first-line treatment is shown in figure 2.

Figure 2 Algorithm for first-line treatment of follicular lymphoma.

Despite the high efficacy of initial treatment regimens, the majority of patients with follicular lymphoma will experience relapse. The goal of maintenance therapy is to extend the duration of remission obtained with first-line treatment; thus, maintenance is only used for patients who respond to first-line therapy. As a result of its consistent efficacy profile and good tolerability, rituximab has been evaluated in several larger trials as maintenance therapy, leading to controversial results.

The RESORT study focused on the question of whether rituximab maintenance prolongs response duration, compared with rituximab treatment at the time of disease progression, in 408 untreated follicular lymphoma patients with a low tumour burden [67]. Following rituximab induction therapy, responders were randomised to rituximab maintenance or retreatment at disease progression until treatment failure. At a median follow-up of 4.5 years, the estimated median time to treatment failure was 4.3 versus 3.9 years, respectively (p = 0.54). Better results were seen for the maintenance arm in terms of 3-year freedom from cytotoxic therapy (95% of patients in the maintenance arm vs 84% in the retreatment arm; p = 0.03). However, these benefits must be weighed against the higher amount of rituximab usage in the maintenance arm. The overall survival in both arms was 94% at 5 years, and both treatment regimens were well tolerated. The authors concluded that retreatment at disease progression when single-agent rituximab is used as front-line therapy in patients with low tumour burden is preferable to maintenance rituximab.

Several other studies have evaluated the use of maintenance rituximab in the setting of front-line treatment or relapsed disease [60, 68–71]. The SAKK 35/98 trial included newly-diagnosed and previously-treated follicular lymphoma patients who were given rituximab induction [60]. At the 10-year follow-up, the median event-free survival was 24 months for the rituximab maintenance arm, compared with 13 months for the observation arm (p <0.001) [28]. Multivariate Cox analysis indicated that prolonged rituximab treatment was the only favourable prognostic factor, leading the authors to suggest that this maintenance regimen could be used regardless of other factors including prior treatment, disease stage or Fc-receptor phenotype [28]. The findings from the SAKK 35/98 trial provide guidance on the rituximab dosing schedule for maintenance therapy (375 mg/m2 every 2 months) [60, 72]. Data from the PRIMA study supported the benefits of this rituximab maintenance schedule for patients who achieve remission after front-line therapy with several immunochemotherapy regimens [73]. The recent 6-year follow-up results of the PRIMA study confirmed these earlier findings [74]. With a median follow-up of 73 months, 6-year progression-free survival was 42.7% in the observation arm versus 59.2% in the rituximab maintenance arm, (HR 0.58, 95% CI 0.48–0.69; p <0.0001). Preplanned subgroup analyses showed that the effect of rituximab maintenance was consistent regardless of age, gender, FLIPI score, induction regimen used and response to induction treatment. There were no unexpected toxicities and the 6-year overall survival rate was similar in both study arms (88.7% in the observation arm vs 87.4% in the maintenance arm).

However, the duration of maintenance therapy is still a matter of discussion. Recent results from the SAKK 35/03 trial provide clarification [75]. This study compared short-term rituximab maintenance (one infusion every 2 months, for a total of four administrations) with a long-term maintenance schedule (one infusion every 2 months for a maximum of 5 years, or until relapse, progression or unacceptable toxicity) in 270 patients with untreated, relapsed, stable, or chemotherapy-resistant follicular lymphoma who had received rituximab induction monotherapy (375 mg/m2). At a median follow-up of 6.4 years, the median event-free survival was 3.4 years (95% CI 2.1–5.3 years) in the short-term arm and 5.3 years (95% CI 3.5 years to not available) in the long-term arm (p = 0.14). A sensitivity analysis focusing on late events showed a statistically significant increase in event-free survival in favour of the long-term maintenance regimen (7.4 years, 95% CI 5.1 to not available compared with 3.5 years, 95% CI 2.1–5.9 years for the short-term arm; p = 0.04). Patients in the long-term arm experienced significantly more adverse effects (p <0.001). No difference in overall survival between the arms was seen. The primary endpoint from this trial showed that long-term rituximab maintenance did not confer a statistically significant benefit in terms of event-free survival compared with the 8-month maintenance treatment schedule.

In Switzerland, rituximab maintenance treatment is frequently used even after a bendamustine-rituximab front-line regimen. The current ESMO guidelines recommend rituximab maintenance therapy according to the schedule established in the PRIMA trial (rituximab 375 mg/m2 every 8 weeks for 2 years) [5].

Nearly all patients will experience disease recurrence or progression. There is no conclusive evidence to guide the management of these patients and, in practice, choice of therapy is driven by factors similar to those for first-line treatment. Not all relapses necessitate immediate treatment; asymptomatic cases may be managed with watchful waiting until treatment is needed. When treatment is needed, a variety of strategies are used. These include rechallenge of the initial treatment regimen (when such treatment has led to remission for more than a year), or use of a non-crossresistant chemotherapy with or without rituximab.

Recently, highly effective immunochemotherapy regimens with fewer toxic effects and the expanding array of new agents have shifted the clinical focus away from stem cell transplantation as a routine treatment option in relapsing follicular lymphoma. However, none of the new agents have demonstrated a potential for cure. Valuable time may be lost with the use of palliative treatments during which the time window for high-dose therapy may close for many eligible patients. Accordingly, in patients fit enough to undergo high-dose chemotherapy with autologous stem cell transplantation, this approach should be strongly considered, especially for those with histologically transformed disease. The curative potential of this approach was recently demonstrated in a large retrospective analysis of 655 patients, with durable remissions irrespective of previous rituximab treatment [76]. Furthermore, patients who experience early treatment failure after front-line immunochemotherapy may benefit from the use of autologous stem cell transplantation within ≤1 year of treatment failure [77].

Radioimmunotherapy is an option for patients with low tumour burden and minimal bone marrow involvement; (90Y)-ibritumomab tiuxetan (Zevalin®) has been shown to induce high response rates and durable remissions in relapsed or refractory low-grade follicular lymphoma [78]. Interestingly, radioimmunotherapy given either as a single agent or as consolidation after induction treatment has been consistently shown to cure a certain fraction of patients with follicular lymphoma. Despite this fact, radioimmunotherapy, although available in Switzerland, remains rarely used. The concern over secondary cancers, the lack of high-quality clinical studies and availability of the many new agents may fuel the reluctance of many clinicians to use this potentially curative treatment for follicular lymphoma.

In Switzerland, the majority of patients with relapsed or resistant disease are treated with various immunochemotherapy regimens. The ESMO guidelines define early relapses as those occurring within 12 to 24 months of treatment [5]. In patients with early relapses, use of a non-cross-resistant treatment regimen is recommended [5]. For patients who relapse within 2 to 3 years of initial treatment, the same first-line regimen may be used, unless the initial treatment contained anthracyclines and retreatment would exceed the cumulative threshold of 450 mg/m2 doxorubicin. Patients with a poor performance status and who showed previous response to rituximab may benefit from rituximab monotherapy [79]. For fit patients with symptomatic disease in need of treatment, several immunochemotherapy regimens may be considered. The bendamustine-rituximab regimen has been used successfully to treat patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma following one to two previous rituximab-based treatments, resulting in 95% overall response and 80% complete response rates [80]. Fludarabine-based regimens are also often used for patients who relapse after alkylator-based therapies [15]. Nevertheless, bendamustine appears to have a better risk-benefit profile than fludarabine in the relapse setting. The StiL-2 study compared the use of bendamustine-rituximab with fludarabine-rituximab in patients with relapsed or refractory indolent NHL [81]. At a median follow-up of 96 months, median progression-free survival in the bendamustine-rituximab arm was 34.2 months versus 11.7 months in the fludarabine-rituximab arm (HR 0.54, 95% CI 0.38–0.72; log-rank test p <0.0001) [81]. Of note, 11% of the patients in the bendamustine-rituximab arm had previously received the same regimen as first-line treatment. Currently, there is no information comparing their response with those who were bendamustine-rituximab naïve. Fludarabine-based regimens are also known to have adverse effects such as haematological toxicities and infections, precluding their use in the elderly or in those with comorbidities [82].

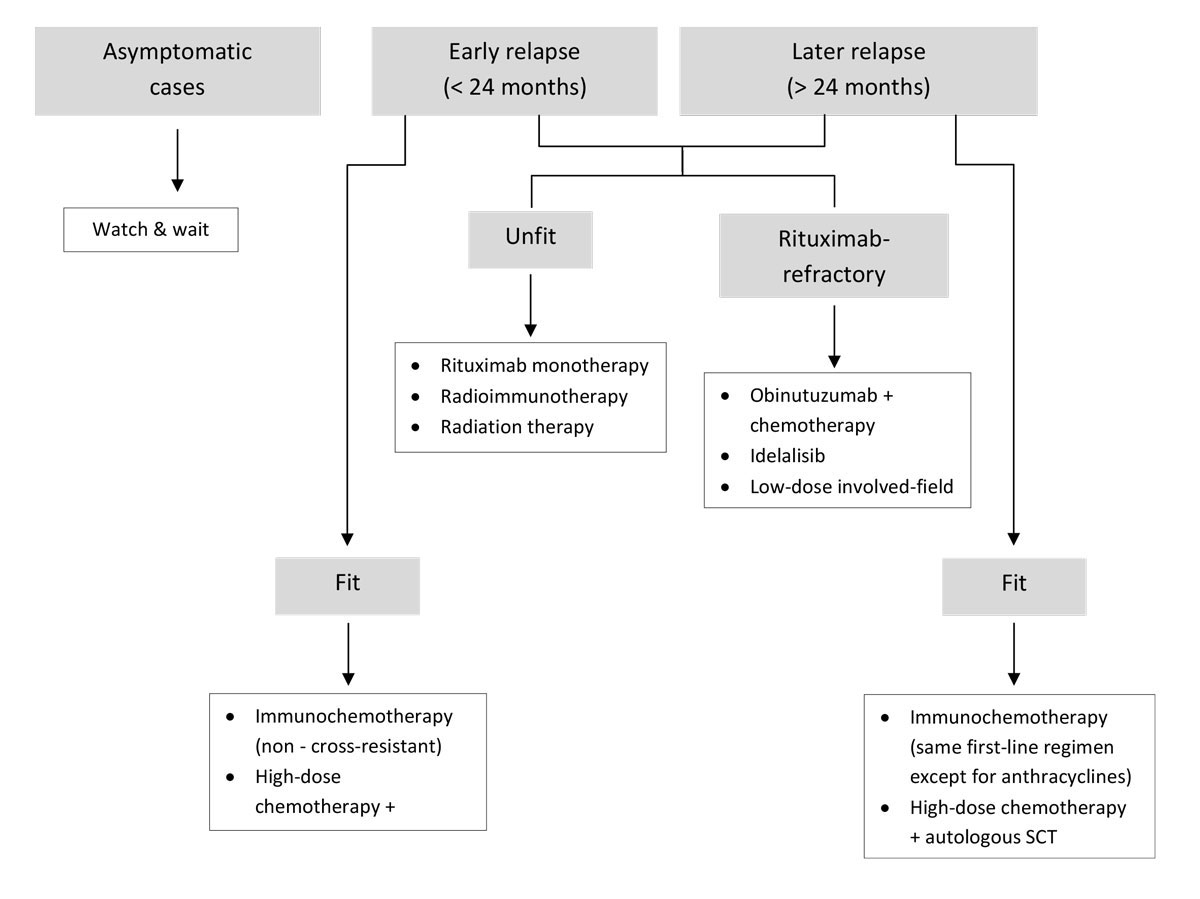

In light of the ubiquitous application of rituximab in front-line treatment regimens, the emergence of rituximab-resistant disease is a problem [83]. The GADOLIN trial tested the efficacy and safety of obinutuzumab plus bendamustine against bendamustine alone in 413 patients who had rituximab-refractory indolent NHL [84]. At a median follow-up of 31.2 months, progression-free survival was significantly longer with obinutuzumab-bendamustine (25.3 months) than with bendamustine monotherapy (14.0 months; p <0.0001). The latest update showed a significant overall survival benefit in favour of obinutuzumab-bendamustine versus bendamustine alone (median not reached vs 53.9 months; p = 0.0061) [85]. Swiss regulatory authorities have recently approved obinutuzumab plus bendamustine followed by obinutuzumab maintenance therapy for follicular lymphoma patients who previously received a rituximab-based therapy. Also approved and licensed in Switzerland after failure of two prior treatments is idelalisib (Zydelig®), a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase δ inhibitor [86]. In a phase II open-label study of 125 patients with relapsed or refractory indolent NHL, idelalisib monotherapy showed antitumour activity and acceptable tolerability, including in 72 patients with follicular lymphoma [87]. Several ongoing trials are underway to evaluate idelalisib in combination with rituximab or rituximab plus bendamustine; however, some have been stopped owing to safety concerns related to idelalisib. Another combination that has shown efficacy in the relapse-refractory setting is lenalidomide-rituximab (R2) [63]. Compared with lenalidomide alone, the lenalidomide-rituximab regimen showed a higher overall response rate (76 vs 53%) and longer time to progression (2 vs 1.1 years), with no increased toxicity [88]. The synergistic effects of this combination warrant further investigation. Finally, the use of low-dose involved-field radiation therapy remains a viable option, particularly for patients with localised relapses. A summary of the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma is shown in figure 3.

Figure 3 Algorithm for the treatment of relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma. SCT = stem cell transplantation.

The annual rate of histological transformation in follicular lymphoma patients is around 3%, although this may be slightly lower in the rituximab era [89]. A re-biopsy is strongly recommended upon disease recurrence and before initiating treatment of relapsed disease, to rule out the presence of transformation to a higher-grade histological subtype. The presence of histological transformation in patients who responded to prior immunochemotherapy is associated with poor outcomes and may warrant more aggressive treatment [90]. PET-CT is widely used not only for staging but also for assessment of interim response to treatment and for evaluating response at the end of treatment [91]. The presence of residual FDG-avidity at the end of first-line treatment may be predictive of poorer clinical outcomes [92, 93], although it is still unclear how PET-positivity should guide the choice of subsequent treatment. The use of PET-CT is especially relevant in patients for whom long progression-free survival is a treatment goal; as such, PET-CT may not be necessary in older patients or in those with significant comorbidities, whose treatment goals are mainly symptomatic. There is evidence that the hepatitis C virus (HCV) may be associated with the development of B cell malignancies including follicular lymphoma [94, 95], and that treatment of HCV may be warranted prior to treatment of the lymphoma itself [96, 97]. For patients who will receive R-CHOP or bendamustine-rituximab, antibiotic prophylaxis may be used (sulphonamide/trimethoprim 960 mg 2–3 times per week, or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 160 mg/800 mg 3 times per week).

There is still no conclusive evidence to support adherence to a specific follow-up schedule. The latest ESMO guidelines provide a basis for the minimal follow-up in patients with follicular lymphoma (table 3).

Table 3 Summary of the ESMO guidelines for the follow-up of patients with follicular lymphoma [5].

| Examination | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Medical history and physical examination |

After localised radiotherapy

Every 6 months for 2 years; thereafter once a year if needed After systemic therapy Every 3–4 months for 2 years; every 6 months for the following 3 years; thereafter once a year |

| Blood counts and routine chemistry tests | Every 6 months for 2 years; thereafter as clinically indicated |

| Thyroid function | After 1, 2 and 5 years in patients who received irradiation of the neck |

| Radiological or ultrasound tests | Every 6 months for 2 years; thereafter once a year up to 5 years (optional) |

| PET-CT | At mid-term and at the end of chemotherapy induction treatment. We suggest that PET-CT is also used at diagnosis to identify areas for potential biopsy and to map fields for localised radiation therapy. |

CT = computed tomography; ESMO = European Society for Medical Oncology; PET = positron emission tomography

Much progress has been made towards achieving excellent overall survival using immunochemotherapy, particularly in those patients with limited-stage disease who respond to anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody treatment. Indeed, the slow course of the disease is at odds with the rapid pace at which new treatments are being developed. The long follow-up required for clinical trials means that some treatment regimens are out of date before study closure [98]. For example, previous studies on rituximab maintenance did not evaluate the efficacy of maintenance or salvage regimens following front-line treatment with bendamustine-rituximab, simply because this was not standard practice at the time of trial design [98]. Furthermore, it is still difficult to extrapolate trial results to all follicular lymphoma patients, because of the heterogeneous nature of the disease. The most urgent unmet need remains with those patients whose disease is not responsive to anti-CD20 treatment regimens and in whom minimal residual disease persists even after immunochemotherapy, as well as in those with early disease progression after first-line treatment. For these patients, it will be essential to explore the efficacy of novel agents and new combinations to achieve prolonged remission and extended survival.

This work was supported by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG, Reinach, Switzerland.

RB: employment by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG; FH: advisory board participation for Roche; CK: employment by Roche; UM: advisory board participation for Roche, Celgene, Gilead and Janssen-Cilag; FS: travel support by Roche Switzerland; CT: research support from Celgene

1 Mounier M , Bossard N , Remontet L , Belot A , Minicozzi P , De Angelis R , et al.; EUROCARE-5 Working Group; CENSUR Working Survival Group. Changes in dynamics of excess mortality rates and net survival after diagnosis of follicular lymphoma or diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: comparison between European population-based data (EUROCARE-5). Lancet Haematol. 2015;2(11):e481–91. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3026(15)00155-6

2 Sant M , Minicozzi P , Mounier M , Anderson LA , Brenner H , Holleczek B , et al.; EUROCARE-5 Working Group. Survival for haematological malignancies in Europe between 1997 and 2008 by region and age: results of EUROCARE-5, a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(9):931–42. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70282-7

3 Anastasia A , Rossi G . Novel Drugs in Follicular Lymphoma. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2016;8(1):e2016061.

4 Cheah CY , Fowler NH . Novel agents for relapsed and refractory follicular lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2018;31(1):41–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2017.11.003

5 Dreyling M , Ghielmini M , Rule S , Salles G , Vitolo U , Ladetto M ; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Newly diagnosed and relapsed follicular lymphoma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v83–90. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw400

6 Hitz F , Ketterer N , Lohri A , Mey U , Pederiva S , Renner C , et al. Diagnosis and treatment of follicular lymphoma. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13247. doi:https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2011.13247.

7 Swerdlow SH , Campo E , Pileri SA , Harris NL , Stein H , Siebert R , et al. The 2016 revision of the World Health Organization classification of lymphoid neoplasms. Blood. 2016;127(20):2375–90. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2016-01-643569

8Swerdlow S, Campo E, Harris N, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. World Health Organization 2017;Volume 2:Revised 4th edition.

9 Vaidyanathan G , Czuczman MS . Follicular lymphoma grade 3: review and updates. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2014;14(6):431–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clml.2014.04.008

10Swerdlow SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO Classification of Tumours of Haematopoietic and Lymphoid Tissue (IARC WHO Classification of Tumours). World Health Organization 2008:4th edition.

11 Koch K , Hoster E , Ziepert M , Unterhalt M , Ott G , Rosenwald A , et al. Clinical, pathological and genetic features of follicular lymphoma grade 3A: a joint analysis of the German low-grade and high-grade lymphoma study groups GLSG and DSHNHL. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(7):1323–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdw185

12 Horn H , Schmelter C , Leich E , Salaverria I , Katzenberger T , Ott MM , et al. Follicular lymphoma grade 3B is a distinct neoplasm according to cytogenetic and immunohistochemical profiles. Haematologica. 2011;96(9):1327–34. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3324/haematol.2011.042531

13 Takata K , Miyata-Takata T , Sato Y , Yoshino T . Pathology of follicular lymphoma. J Clin Exp Hematop. 2014;54(1):3–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3960/jslrt.54.3

14 Luminari S , Bellei M , Biasoli I , Federico M . Follicular lymphoma - treatment and prognostic factors. Rev Bras Hematol Hemoter. 2012;34(1):54–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.5581/1516-8484.20120015

15 Kahl BS , Yang DT . Follicular lymphoma: evolving therapeutic strategies. Blood. 2016;127(17):2055–63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2015-11-624288

16 Salles GA . Clinical features, prognosis and treatment of follicular lymphoma. Hematology (Am Soc Hematol Educ Program). 2007;2007(1):216–25. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/asheducation-2007.1.216

17 Cheson BD , Fisher RI , Barrington SF , Cavalli F , Schwartz LH , Zucca E , et al.; Alliance, Australasian Leukaemia and Lymphoma Group; Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Consortium; Italian Lymphoma Foundation; European Organisation for Research; Treatment of Cancer/Dutch Hemato-Oncology Group; Grupo Español de Médula Ósea; German High-Grade Lymphoma Study Group; German Hodgkin’s Study Group; Japanese Lymphorra Study Group; Lymphoma Study Association; NCIC Clinical Trials Group; Nordic Lymphoma Study Group; Southwest Oncology Group; United Kingdom National Cancer Research Institute. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–68. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800

18 Wöhrer S , Jaeger U , Kletter K , Becherer A , Hauswirth A , Turetschek K , et al. 18F-fluoro-deoxy-glucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG-PET) visualizes follicular lymphoma irrespective of grading. Ann Oncol. 2006;17(5):780–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl014

19 Barrington SF , Mikhaeel NG . PET Scans for Staging and Restaging in Diffuse Large B-Cell and Follicular Lymphomas. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2016;11(3):185–95. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11899-016-0318-1

20 Palacio C , Acebedo G , Navarrete M , Ruiz-Marcellán C , Sanchez C , Blanco A , et al. Flow cytometry in the bone marrow evaluation of follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. Haematologica. 2001;86(9):934–40.

21 Graf BL , Korte W , Schmid L , Schmid U , Cogliatti SB . Impact of aspirate smears and trephine biopsies in routine bone marrow diagnostics: a comparative study of 141 cases. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135(9-10):151–9.

22 Payne K , Wright P , Grant JW , Huang Y , Hamoudi R , Bacon CM , et al. BIOMED-2 PCR assays for IGK gene rearrangements are essential for B-cell clonality analysis in follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2011;155(1):84–92. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08803.x

23 Einerson RR , Kurtin PJ , Dayharsh GA , Kimlinger TK , Remstein ED . FISH is superior to PCR in detecting t(14;18)(q32;q21)-IgH/bcl-2 in follicular lymphoma using paraffin-embedded tissue samples. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124(3):421–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1309/BLH8MMK85UBQ4K6R

24 Camacho FI , Bellas C , Corbacho C , Caleo A , Arranz-Sáez R , Cannata J , et al. Improved demonstration of immunohistochemical prognostic markers for survival in follicular lymphoma cells. Mod Pathol. 2011;24(5):698–707. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/modpathol.2010.237

25 Bai B , Huang HQ . Individualized management of follicular lymphoma. Linchuang Zhongliuxue Zazhi. 2015;4(1):7.

26 Solal-Céligny P , Roy P , Colombat P , White J , Armitage JO , Arranz-Saez R , et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood. 2004;104(5):1258–65. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-12-4434

27 Pastore A , Jurinovic V , Kridel R , Hoster E , Staiger AM , Szczepanowski M , et al. Integration of gene mutations in risk prognostication for patients receiving first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma: a retrospective analysis of a prospective clinical trial and validation in a population-based registry. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):1111–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00169-2

28 Martinelli G , Schmitz SF , Utiger U , Cerny T , Hess U , Bassi S , et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with follicular lymphoma receiving single-agent rituximab at two different schedules in trial SAKK 35/98. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(29):4480–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.28.4786

29 McNamara C , Davies J , Dyer M , Hoskin P , Illidge T , Lyttelton M , et al.; Haemato-oncology Task Force of the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH); British Society for Haematology Committee. Guidelines on the investigation and management of follicular lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2012;156(4):446–67. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2141.2011.08969.x

30 Brice P , Bastion Y , Lepage E , Brousse N , Haïoun C , Moreau P , et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15(3):1110–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.1110

31 Friedberg JW , Byrtek M , Link BK , Flowers C , Taylor M , Hainsworth J , et al. Effectiveness of first-line management strategies for stage I follicular lymphoma: analysis of the National LymphoCare Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(27):3368–75. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.40.6546

32 Pugh TJ , Ballonoff A , Newman F , Rabinovitch R . Improved survival in patients with early stage low-grade follicular lymphoma treated with radiation: a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database analysis. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3843–51. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.25149

33 Lowry L , Smith P , Qian W , Falk S , Benstead K , Illidge T , et al. Reduced dose radiotherapy for local control in non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a randomised phase III trial. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(1):86–92. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.013

34 Haas RL , Poortmans P , de Jong D , Aleman BM , Dewit LG , Verheij M , et al. High response rates and lasting remissions after low-dose involved field radiotherapy in indolent lymphomas. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(13):2474–80. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2003.09.542

35 Luthy SK , Ng AK , Silver B , Degnan KO , Fisher DC , Freedman AS , et al. Response to low-dose involved-field radiotherapy in patients with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2008;19(12):2043–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdn529

36 Hoskin PJ , Kirkwood AA , Popova B , Smith P , Robinson M , Gallop-Evans E , et al. 4 Gy versus 24 Gy radiotherapy for patients with indolent lymphoma (FORT): a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):457–63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70036-1

37Buske C, Dreyling M, Herold M, Willenbacher W. Onkopedia guidelines: follicular lymphoma. https://wwwonkopedia-guidelinesinfo/en/onkopedia/guidelines/follicular-lymphoma/@@view/html/indexhtml 2012. Accessed 12 August 2017.

38 Zimmermann M , Oehler C , Mey U , Ghadjar P , Zwahlen DR . Radiotherapy for Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: still standard practice and not an outdated treatment option. Radiat Oncol. 2016;11(1):110. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/s13014-016-0690-y

39 Brady JL , Bonkley MS , Hajj C , et al. Outcome for curative radiotherapy for localised follicular lymphoma in the era of 18F-FDG PET-CT staging: an international collaborative study on behalf of ILROG. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35(S2). [Abstract 11].

40Alperovich A, Moskowitz C, Younes A, et al. Impact of PET Staging of Follicular Lymphoma on Treatment Outcomes and Prognosis. Blood 2017;ASH 59th Annual Meeting Abstracts:Abstract 1494.

41 Witzens-Harig M , Hensel M , Unterhalt M , Herfarth K . Treatment of limited stage follicular lymphoma with Rituximab immunotherapy and involved field radiotherapy in a prospective multicenter Phase II trial-MIR trial. BMC Cancer. 2011;11(1):87. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-11-87

42 Herfarth K , Witzens-Harig M . IF Bestrahlung und Rituximab im frühen Stadium des follikulären Lymphomas: 5 Jahres Daten des Heidelberger MIR Subkollektivs. Strahlenther Onkol. 2017;193(Suppl):S6.

43 Macmanus MP , Fisher R , Roos D , O’Brien P , Macann A , Tsang R . CVP or R-CVP given after involved-field radiotherapy improves prograssion free survival in stage I-II follicular lymphoma: results of an international randmoized trial. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35(S2). [Abstract 12].

44 Solal-Céligny P , Bellei M , Marcheselli L , Pesce EA , Pileri S , McLaughlin P , et al. Watchful waiting in low-tumor burden follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era: results of an F2-study database. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(31):3848–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.4474

45 Yuda S , Maruyama D , Maeshima AM , Makita S , Kitahara H , Miyamoto KI , et al. Influence of the watch and wait strategy on clinical outcomes of patients with follicular lymphoma in the rituximab era. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(12):2017–22. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2800-1

46 Ardeshna KM , Qian W , Smith P , Braganca N , Lowry L , Patrick P , et al. Rituximab versus a watch-and-wait approach in patients with advanced-stage, asymptomatic, non-bulky follicular lymphoma: an open-label randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15(4):424–35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70027-0

47 Castellino A , Santambrogio E , Nicolosi M , Botto B , Boccomini C , Vitolo U . Follicular Lymphoma: The Management of Elderly Patient. Mediterr J Hematol Infect Dis. 2017;9(1):e2017009. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4084/mjhid.2017.009

48 Rummel MJ , Niederle N , Maschmeyer G , Banat GA , von Grünhagen U , Losem C , et al.; Study group indolent Lymphomas (StiL). Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1203–10. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61763-2

49 Flinn IW , van der Jagt R , Kahl BS , Wood P , Hawkins TE , Macdonald D , et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood. 2014;123(19):2944–52. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2013-11-531327

50 Flinn I , van der Jagt R , Chang J , et al. First-line treatment of iNHL or MCL patients with BR or R-CHOP/R-CVP: Results of the BRIGHT 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(Suppl).

51 Federico M , Luminari S , Dondi A , Tucci A , Vitolo U , Rigacci L , et al. R-CVP versus R-CHOP versus R-FM for the initial treatment of patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: results of the FOLL05 trial conducted by the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(12):1506–13. doi:.. Corrected in: J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(10):1095https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.45.0866

52 Luminari S , Tarantino V , Anastasia A , et al. Long term results of the FOLLO5 randomized study comparing R-CVP with R-CHOP and R-FM as first line therapy in patients with advanced stage follicular lymphoma: A FIL study. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35(S2). [Abstract 15].

53 Brugger W , Ghielmini M . Bendamustine in indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a practice guide for patient management. Oncologist. 2013;18(8):954–64. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0079

54 Jacobson CA , Freedman AS . First-line treatment of indolent lymphoma: axing CHOP? Lancet. 2013;381(9873):1163–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61965-5

55 Mondello P , Steiner N , Willenbacher W , Wasle I , Zaja F , Zambello R , et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus R-CHOP as first-line treatment for patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: evidence from a multicenter, retrospective study. Ann Hematol. 2016;95(7):1107–14. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00277-016-2668-0

56 Luminari S , Goldaniga M , Cesaretti M , Orsucci L , Tucci A , Pulsoni A , et al. A phase II study of bendamustine in combination with rituximab as initial treatment for patients with indolent non-follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma. 2016;57(4):880–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3109/10428194.2015.1091934

57 Yamaguchi T , Morita T , Takahashi Y , Tsuda K , Mori J . Treatment for patients with indolent and mantle cell lymphoma. Lancet. 2013;382(9898):1094–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62018-8

58Colombat P, Brousse N, Morschhauser F, et al. Single treatment with rituximab monotherapy for low-tumor burden follicular lymphoma (FL): survival analysis with extended follow-up (F/Up) of 7 years. ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts 2006;108:486.

59 Colombat P , Salles G , Brousse N , Eftekhari P , Soubeyran P , Delwail V , et al. Rituximab (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody) as single first-line therapy for patients with follicular lymphoma with a low tumor burden: clinical and molecular evaluation. Blood. 2001;97(1):101–6. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V97.1.101

60 Ghielmini M , Schmitz SF , Cogliatti SB , Pichert G , Hummerjohann J , Waltzer U , et al. Prolonged treatment with rituximab in patients with follicular lymphoma significantly increases event-free survival and response duration compared with the standard weekly x 4 schedule. Blood. 2004;103(12):4416–23. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2003-10-3411

61 Ghielmini M , Rufibach K , Salles G , Leoncini-Franscini L , Léger-Falandry C , Cogliatti S , et al. Single agent rituximab in patients with follicular or mantle cell lymphoma: clinical and biological factors that are predictive of response and event-free survival as well as the effect of rituximab on the immune system: a study of the Swiss Group for Clinical Cancer Research (SAKK). Ann Oncol. 2005;16(10):1675–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdi320

62 Gribben JG , Fowler N , Morschhauser F . Mechanisms of action of lenalidomide in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(25):2803–11. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.5363

63 Arora M , Gowda S , Tuscano J . A comprehensive review of lenalidomide in B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Ther Adv Hematol. 2016;7(4):209–21. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/2040620716652861

64Celgene. Celgene and LYSARC Provide Update on Phase III ‘RELEVANCE' Study of REVLIMID® in Combination with Rituximab (R2) for the Treatment of Previously Untreated Patients with Follicular Lymphoma. Press release 21 December 2017:http://ir.celgene.com/releasedetail.cfm?releaseid=1052524.

65 Fowler N , Nastoupil L , de Vos S , et al. Ibrutinib Combined with Rituximab in Treatment-Naive Patients with Follicular Lymphoma: Arm 1 + Arm 2 Results from a Multicenter, Open-Label Phase 2 Study. Blood. 2016;128(22). [Abstract 1804].

66 Marcus R , Davies A , Ando K , Klapper W , Opat S , Owen C , et al. Obinutuzumab for the First-Line Treatment of Follicular Lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1331–44. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1614598

67 Kahl BS , Hong F , Williams ME , Gascoyne RD , Wagner LI , Krauss JC , et al. Rituximab extended schedule or re-treatment trial for low-tumor burden follicular lymphoma: eastern cooperative oncology group protocol e4402. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(28):3096–102. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.5853

68 Sousou T , Friedberg J . Rituximab in indolent lymphomas. Semin Hematol. 2010;47(2):133–42. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1053/j.seminhematol.2010.01.003

69 Forstpointner R , Unterhalt M , Dreyling M , Böck HP , Repp R , Wandt H , et al.; German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Maintenance therapy with rituximab leads to a significant prolongation of response duration after salvage therapy with a combination of rituximab, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone (R-FCM) in patients with recurring and refractory follicular and mantle cell lymphomas: Results of a prospective randomized study of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). Blood. 2006;108(13):4003–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-04-016725

70 Hochster H , Weller E , Gascoyne RD , Habermann TM , Gordon LI , Ryan T , et al. Maintenance rituximab after cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone prolongs progression-free survival in advanced indolent lymphoma: results of the randomized phase III ECOG1496 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(10):1607–14. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.17.1561

71 van Oers MH , Klasa R , Marcus RE , Wolf M , Kimby E , Gascoyne RD , et al. Rituximab maintenance improves clinical outcome of relapsed/resistant follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma in patients both with and without rituximab during induction: results of a prospective randomized phase 3 intergroup trial. Blood. 2006;108(10):3295–301. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2006-05-021113

72 Berinstein NL , Grillo-López AJ , White CA , Bence-Bruckler I , Maloney D , Czuczman M , et al. Association of serum Rituximab (IDEC-C2B8) concentration and anti-tumor response in the treatment of recurrent low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 1998;9(9):995–1001. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1008416911099

73 Salles G , Seymour JF , Offner F , López-Guillermo A , Belada D , Xerri L , et al. Rituximab maintenance for 2 years in patients with high tumour burden follicular lymphoma responding to rituximab plus chemotherapy (PRIMA): a phase 3, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9759):42–51. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62175-7

74 Salles G , Seymour JF , Feugier P , et al. Updated 6 Year Follow-Up Of The PRIMA Study Confirms The Benefit Of 2-Year Rituximab Maintenance In Follicular Lymphoma Patients Responding To Frontline Immunochemotherapy. Blood. 2013;122:Abstract 509.

75 Taverna C , Martinelli G , Hitz F , Mingrone W , Pabst T , Cevreska L , et al. Rituximab Maintenance for a Maximum of 5 Years After Single-Agent Rituximab Induction in Follicular Lymphoma: Results of the Randomized Controlled Phase III Trial SAKK 35/03. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):495–500. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.61.3968

76 Jiménez-Ubieto A , Grande C , Caballero D , Yáñez L , Novelli S , Hernández-Garcia MT , et al. Autologous Stem Cell Transplantation for Follicular Lymphoma: Favorable Long-Term Survival Irrespective of Pretransplantation Rituximab Exposure. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2017;23(10):1631–40. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbmt.2017.05.021

77 Casulo C , Friedberg JW , Ahn KW , Flowers CR , DiGilio A . Autologous transplantation improves survival in patients with follicular lymphoma experiencing early therapy failure after frontline chemoimmunotherapy: an NLCS and CIBMTS analysis. Hematol Oncol. 2017;35(S2). [Abstract 226].

78 Illidge T , Morschhauser F . Radioimmunotherapy in follicular lymphoma. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol. 2011;24(2):279–93. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beha.2011.03.005

79 Tobinai K , Igarashi T , Itoh K , Kurosawa M , Nagai H , Hiraoka A , et al.; IDEC-C2B8 Study Group. Rituximab monotherapy with eight weekly infusions for relapsed or refractory patients with indolent B cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma mostly pretreated with rituximab: a multicenter phase II study. Cancer Sci. 2011;102(9):1698–705. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1349-7006.2011.02001.x

80 Matsumoto K , Takayama N , Aisa Y , Ueno H , Hagihara M , Watanabe K , et al.; Keio BRB Study Group. A phase II study of bendamustine plus rituximab in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma and mantle cell lymphoma previously treated with rituximab: BRB study. Int J Hematol. 2015;101(6):554–62. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12185-015-1767-3

81 Rummel M , Kaiser U , Balser C , Stauch M , Brugger W , Welslau M , et al.; Study Group Indolent Lymphomas. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus fludarabine plus rituximab for patients with relapsed indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: a multicentre, randomised, open-label, non-inferiority phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(1):57–66. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00447-7

82 Moita F , Esteves S , Klose T , Koehler M , Silva MG . Are Fludarabine Based Regimens Still Adequate for Relapsed/Refractory Follicular Lymphoma? An 18-Year Single-Center Experience. Ann Hematol Oncol. 2015;2(8):1059.

83 MacDonald D , Prica A , Assouline S , Christofides A , Lawrence T , Sehn LH . Emerging therapies for the treatment of relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(6):407–17. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3747/co.23.3405

84 Sehn LH , Chua N , Mayer J , Dueck G , Trněný M , Bouabdallah K , et al. Obinutuzumab plus bendamustine versus bendamustine monotherapy in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma (GADOLIN): a randomised, controlled, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(8):1081–93. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30097-3

85 Cheson BD , Trneny M , Bouabdallah K , et al. Obinutuzumab plus Bendamustine Followed by Obinutuzumab Maintenance Prolongs Overall Survival Compared with Bendamustine Alone in Patients with Rituximab-Refractory Indolent Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma: Updated Results of the GADOLIN Study. Blood. 2016;128(22). [ASH Annual Meeting Abstracts].

86 Barrientos JC . Idelalisib for the treatment of indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a review of its clinical potential. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:2945–53. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2147/OTT.S102573

87 Gopal AK , Kahl BS , de Vos S , Wagner-Johnston ND , Schuster SJ , Jurczak WJ , et al. PI3Kδ inhibition by idelalisib in patients with relapsed indolent lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(11):1008–18. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1314583

88 Leonard JP , Jung SH , Johnson J , Pitcher BN , Bartlett NL , Blum KA , et al. Randomized Trial of Lenalidomide Alone Versus Lenalidomide Plus Rituximab in Patients With Recurrent Follicular Lymphoma: CALGB 50401 (Alliance). J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(31):3635–40. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.59.9258

89 Link BK , Maurer MJ , Nowakowski GS , Ansell SM , Macon WR , Syrbu SI , et al. Rates and outcomes of follicular lymphoma transformation in the immunochemotherapy era: a report from the University of Iowa/MayoClinic Specialized Program of Research Excellence Molecular Epidemiology Resource. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(26):3272–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.48.3990

90 Sarkozy C , Trneny M , Xerri L , Wickham N , Feugier P , Leppa S , et al. Risk Factors and Outcomes for Patients With Follicular Lymphoma Who Had Histologic Transformation After Response to First-Line Immunochemotherapy in the PRIMA Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(22):2575–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7163

91 Barrington SF , Mikhaeel NG , Kostakoglu L , Meignan M , Hutchings M , Müeller SP , et al. Role of imaging in the staging and response assessment of lymphoma: consensus of the International Conference on Malignant Lymphomas Imaging Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3048–58. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.53.5229

92 Tychyj-Pinel C , Ricard F , Fulham M , Fournier M , Meignan M , Lamy T , et al. PET/CT assessment in follicular lymphoma using standardized criteria: central review in the PRIMA study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2014;41(3):408–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-013-2441-8

93 Wong-Sefidan I , Byrtek M , Zhou X , Friedberg JW , Flowers CR , Zelenetz AD , et al. [18F] Positron emission tomography response after rituximab-containing induction therapy in follicular lymphoma is an independent predictor of survival after adjustment for FLIPI in academic and community-based practice. Leuk Lymphoma. 2017;58(4):809–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1080/10428194.2016.1213824

94 Maciocia N , O’Brien A , Ardeshna K . Remission of Follicular Lymphoma after Treatment for Hepatitis C Virus Infection. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(17):1699–701. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1513288

95 Mihăilă RG . Hepatitis C virus - associated B cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(27):6214–23. doi:.https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v22.i27.6214

96 Arcaini L , Vallisa D , Rattotti S , Ferretti VV , Ferreri AJ , Bernuzzi P , et al. Antiviral treatment in patients with indolent B-cell lymphomas associated with HCV infection: a study of the Fondazione Italiana Linfomi. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(7):1404–10. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdu166

97 Sultanik P , Klotz C , Brault P , Pol S , Mallet V . Regression of an HCV-associated disseminated marginal zone lymphoma under IFN-free antiviral treatment. Blood. 2015;125(15):2446–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1182/blood-2014-12-618652

98 Tees MT , Flinn IW . Maintenance Therapies in Indolent Lymphomas: should Recent Data Change the Standard of Care? Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2017;18(3):16. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-017-0459-z

This work was supported by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG, Reinach, Switzerland.

RB: employment by Roche Pharma (Schweiz) AG; FH: advisory board participation for Roche; CK: employment by Roche; UM: advisory board participation for Roche, Celgene, Gilead and Janssen-Cilag; FS: travel support by Roche Switzerland; CT: research support from Celgene