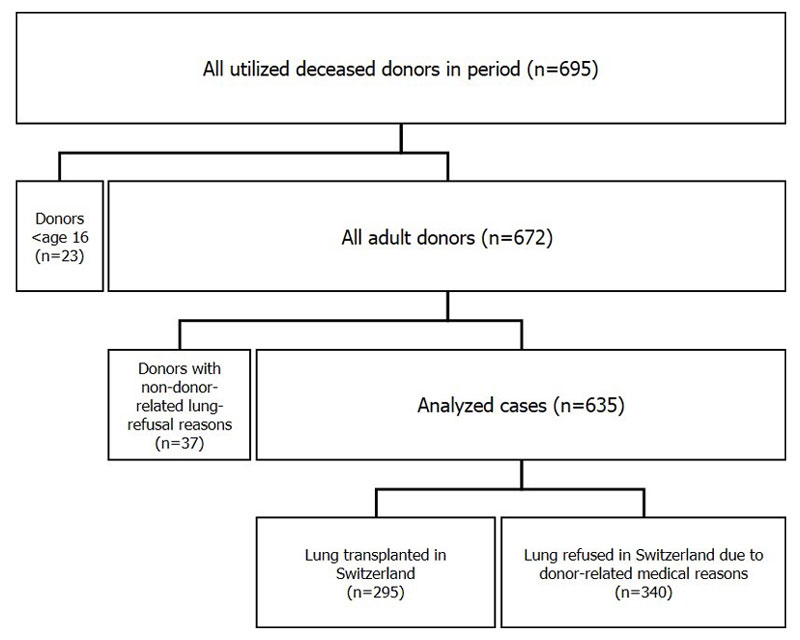

Figure 1 Flowchart of all utilised Swiss deceased donors 2007–2014. The group “lungs transplanted in Switzerland” included double (n = 285), left (n = 3) and right (n = 6) lung transplants and one split lung transplant.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2018.14614

Donor lungs for transplantation are a scarce resource. One possibility for expanding the donor pool is to consider extended-criteria donors – sometimes also called marginal donors – as potential donors. These are donors with conditions that might limit the chance of successful donation and transplantation [1]. In the light of ever growing waiting lists worldwide, the use of extended-criteria donors has become more widely accepted, not only in the field of lung transplantation [2–6].

However, there is no international consensus on a defined set of criteria for extended-criteria donors, nor are there any standardised thresholds for individual criteria [1]. In Europe, no evidence-based studies exist to assist the definition of an extended-criteria donor, which is why different transplant programmes and transplant centres use different concepts of an extended-criteria donor [1]. In Switzerland, the current practice of using extended-criteria donors in lung transplantation draws on concepts that are guided by a publication of Orens and colleagues in 2003 [6]. Since then, organ viability criteria have been continually adjusted and refined, according to the experience of professionals in lung transplantation. These adaptations were based on the current clinical practice and literature, and also accounted for changes within the population constituting the current donor pool.

There are scoring systems aiming to assess the quality of donor lungs for transplantation based on the risks of potentially compromised organ function in the recipient. Most of these risk scoring systems also include one or several extended donor criteria [1]. In the present study, we evaluated two different donor quality scores in a retrospective analysis of Swiss donor data [7, 8]. We evaluated whether these scores can discriminate between lungs that were procured and transplanted and lungs that were refused by Swiss transplant centres – in other words, whether the score values reflect the likelihood that a lung is deemed to be transplantable by Swiss experts in lung transplantation.

Comprehensive and compulsory donor data as captured by the donor hospital staff with the national online application “Swiss Organ Allocation System” (SOAS) were retrospectively analysed. Included were all Swiss deceased donors from whom at least one organ was transplanted (utilised donors) from 1 July 2007 to 30 June 2014 (n = 695). Data entry was under the supervision of Swisstransplant to guarantee compliance with the Swiss Transplantation Law and to enable comparable data quality among different donor hospitals. Both donors after brain death and donors after cardiocirculatory death were included.

Excluded from the subsequent analysis were donors below the age of sixteen (n = 23) and donors whose lungs were refused by Swiss transplant centres for reasons not primarily related to the donor’s medical condition or to organ quality (n = 37). These non-medical refusal reasons include absence of consent by donor/family (specific exclusion of the lung from transplantation as documented with a donor card or expressed by the next of kin; n = 23), logistic reasons (n = 2), procurement accidents (n = 1) and absence of a compatible Swiss recipient (n = 11). The last was mostly due to organ size and weight mismatch, blood group incompatibility or an incompatible virology status between donor and recipient and includes nine donors whose lungs were eventually transplanted abroad.

The term “accepted lung donor” in this article refers to a donor from whom at least one lung lobe was transplanted in Switzerland. Likewise, the term “refused lung donor” refers to the refusal of both donor lungs in Switzerland primarily for donor-related medical reasons. Figure 1 shows derivation and composition of analysed cases.

Figure 1 Flowchart of all utilised Swiss deceased donors 2007–2014. The group “lungs transplanted in Switzerland” included double (n = 285), left (n = 3) and right (n = 6) lung transplants and one split lung transplant.

Smits et al. [7] described the development and the evaluation of a quality scoring system for lung donors based on a previous publication by Oto et al. [9]. They derived this Eurotransplant donor score (EDS) through a retrospective analysis of different extended donor criteria, which were weighted with points according to the odds ratio of whether the lung was accepted or discarded. For each donor, a score was obtained by adding these points: a low score reflects a good quality donor. The EDS thus reflects the aggregated perceived risk of several experts in lung transplantation in various centres in the Eurotransplant network in the period from 1999–2007 [7].

Some of the clinical tests performed in the Eurotransplant allocation programme are not routinely performed in Switzerland or their recording in the national database SOAS is not compulsory when reporting a donor. Because of such differences in data capture, the original EDS had to be slightly adapted for the present analysis (aEDS). In the following paragraphs we describe how the EDS was adapted to enable application on Swiss donor data:

An overview of the aEDS is given in table 2 in the results section.

Like the EDS, the Zurich donor score (ZDS) is an aggregated quality measurement for the assessment of donor lungs. It was developed at the University Hospital of Zurich, one of two centres for lung transplantation in Switzerland. The ZDS was based on clinical experience and expert knowledge, and the criteria are weighted with either zero or one point. The ZDS originally comprised five extended donor criteria and five comorbidities, including systemic arterial hypertension, cardiac disease, insulin dependent diabetes mellitus, chronic renal disease and liver disease [8].

For the present analysis, the score has been limited to four extended-donor criteria, shown in table 3 (below). An age threshold of 65 years and a value for the ratio of partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) of 250 mm Hg were found to be most discriminative in a preliminary analysis and therefore used in our adapted score (aZDS). The score reflects the aggregated perceived risk of local experts in lung transplantation: a low score reflects a good quality lung donor.

Donors were divided into two groups, lung transplanted and lung refused in Switzerland. Between these groups, baseline donor characteristics were compared for quantitative variables by using the t-test, or if the normality assumption was not met, by non-parametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test. For qualitative variables Pearson’s chi-square test was used, or Fisher’s exact test when the sample size was small. If not otherwise indicated, two-sided statistical models were applied (non-directional hypotheses) and p-values of less than 0.05 were considered significant. For Wilcoxon’s rank-sum test, the statistic W, the significance level (p-value), and the standardised effect size r, which measures the strength of association (an absolute value of r >0.1, r >0.3 and r >0.5 means a small, medium and large effect, respectively) are reported in the text. For the Pearson’s chi-square test the statistic χ2 with associated degrees of freedom (in brackets) and the significance level (p-value) are reported in the text.

The donor quality scores were considered to be continuous variables and their effect on lung transplantation in Switzerland (transplanted/refused) was analysed independently, using univariate logistic regression. The ability of the scores to discriminate between the outcomes (lung transplanted vs refused) was assessed by calculating the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC). The value of AUC lies between 0.5 and 1.0: 0.5 denotes a random predictor and 1.0 denotes a perfect classifier. Values were interpreted as follows: 0.9–1.0 = excellent; 0.8–0.9 = good; 0.7–0.8 = fair; 0.6–0.7 = poor; 0.5–0.6 = fail [10].

For all statistical analyses, the freely available software R (version 3.4.1) was used [11].

Of the 635 utilised adult donors included in our analysis, 295 were accepted as lung donors by one of the two lung transplant centres in Switzerland (acceptance rate 46%). In contrast, 340 donors were refused by the Swiss lung transplant centres for primarily donor-related medical reasons (refusal rate 54%). Detailed donor characteristics are shown in table 1.

Table 1 Donor baseline characteristics for accepted and refused lung donors.

|

Accepted lung donors

n (%) |

Refused lung donors

n (%) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 295 (46%) | 340 (54%) | |

| Male | 169 (57%) | 196 (58%) | 0.927 |

| Female | 126 (43%) | 144 (42%) | |

| Age (median and IQR; years) | 51.0 (38.0–62.0) | 59.0 (47.0–68.0) | <0.001** |

| BMI (median and IQR; kg/m2) | 24.2 (22.6–26.0) | 25.7 (23.5–27.8) | <0.001** |

| Cause of admission to ICU | |||

| Trauma | 84 (30%) | 69 (22%) | 0.019* |

| Cardiac arrest | 73 (25%) | 109 (32%) | 0.048* |

| Respiratory arrest | 65 (22%) | 97 (29%) | 0.060 |

| Reanimation | 56 (21%) | 97 (30%) | 0.011* |

| Cause of death | |||

| Cerebral haemorrhage | 171 (58%) | 200 (59%) | 0.827 |

| Cerebral trauma | 70 (24%) | 56 (16%) | 0.022* |

| Anoxia | 49 (17%) | 81 (24%) | 0.025* |

| Other | 5 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 0.360 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 126 (44%) | 120 (38%) | 0.116 |

| Heart disease | 46 (16%) | 85 (26%) | 0.002* |

| Diabetes mellitus | 17 (6%) | 33 (10%) | 0.056 |

| Lung disease | 14 (5%) | 55 (17%) | <0.001** |

| Kidney disease | 11 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 0.883 |

| Liver disease | 8 (3%) | 26 (8%) | 0.004* |

| Cancer | 6 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 0.540 |

BMI = body mass index; ICU = intensive care unit; IQR = interquartile range For cause of admission to ICU and comorbidities more than one item per donor is possible such that percentages do not add up to 100. Donor characteristics with p-values below 0.05 are considered to differ significantly between the groups of accepted vs refused lung donors. * p <0.05, ** p <0.001

Accepted lung donors were significantly younger (W = 63048, p <0.001, r = −0.22) and had a significantly lower body mass index (W = 63048, p <0.001, r = −0.23) than refused lung donors. All analysed causes of admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) – except for respiratory arrest – were significantly associated with the outcome whether or not the donor lung was accepted by Swiss transplant centres. The corresponding values of the Pearson’s chi-square test were: χ2 (1) = 3.92, p <0.05 for cardiac arrest; χ2 (1) = 6.45, p <0.05 for reanimation; and χ2 (1) = 5.51, p <0.05 for trauma. Accepted lung donors died significantly less often from anoxia compared with refused lung donors: χ2 (1) = 5.05, p <0.05. Conversely, cerebral trauma was significantly more common in accepted lung donors than in refused lung donors: χ2 (1) = 5.23, p <0.05. Of seven analysed comorbidities, three were found to be significantly less common in accepted lung donors than in refused lung donors: heart disease, χ2 (1) = 10.07, p <0.05; lung disease, χ2 (1) = 21.99, p <0.001; and liver disease, χ2 (1) = 8.10, p <0.05.

Table 2 shows how the aEDS is built and how the different criteria are weighted. The distribution of individual criteria between the two donor groups of accepted and refused lung donors is presented. The same is shown for aZDS in table 3.

Table 2 Composition of the adapted Eurotransplant donor score (aEDS) for accepted vs refused lung donors.

| Criteria | Score points (aEDS) |

Accepted lung donors

n (%) |

Refused lung donors

n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1–15 | 295 (46%) | 340 (54%) |

| Donor age (years) | |||

| <55 | 1 | 168 (57%) | 139 (41%) |

| 55–59 | 2 | 36 (12%) | 38 (11%) |

| ≥60 | 3 | 91 (31%) | 163 (48%) |

| Cancer* | |||

| No | 1 | 285 (97%) | 313 (92%) |

| Yes | 4 | 6 (2%) | 9 (3%) |

| Not available | 1 | 4 (1%) | 18 (5%) |

| Smoking history | |||

| No | 1 | 146 (49%) | 115 (34%) |

| Yes | 2 | 133 (45%) | 200 (59%) |

| Not available | 1 | 16 (5%) | 25 (7%) |

| Chest x-ray* | |||

| Normal | 1 | 148 (50%) | 79 (23%) |

| Not normal | 2 | 142 (48%) | 240 (71%) |

| Not available | 1 | 5 (2%) | 21 (6%) |

| PaO2/FiO2 (mm Hg) | |||

| >350 | 1 | 166 (56%) | 82 (24%) |

| 301–350 | 2 | 45 (15%) | 42 (12%) |

| ≤300 | 3 | 61 (21%) | 141 (41%) |

| Not available | 2 | 23 (8%) | 75 (22%) |

PaO2/FiO2 = ratio of partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen * Definition differs from the original EDS. The criterion “bronchoscopy” in the original EDS was excluded in the adapted version (see methods section for details).

Table 3 Composition of the adapted Zurich donor score (aZDS) for accepted vs refused lung donors.

| Criteria | Score points (aZDS) |

Accepted lung donors

n (%) |

Refused lung donors

n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 0–4 | 295 (46%) | 340 (54%) |

| Donor age (years) | |||

| <65 | 0 | 244 (83%) | 224 (66%) |

| ≥65 | 1 | 51 (17%) | 116 (34%) |

| Smoking history (pack-years*) | |||

| <20 | 0 | 197 (67%) | 149 (44%) |

| ≥20 | 1 | 62 (21%) | 122 (36%) |

| Not available | 0 | 36 (12%) | 69 (20%) |

| Chest x-ray | |||

| Normal | 0 | 148 (50%) | 79 (23%) |

| Not normal | 1 | 142 (48%) | 240 (71%) |

| Not available | 0 | 5 (2%) | 21 (6%) |

| PaO2/FiO2 (mm Hg) | |||

| >250 | 0 | 245 (83%) | 158 (46%) |

| ≤250 | 1 | 27 (9%) | 107 (31%) |

| Not available | 0 | 23 (8%) | 75 (22%) |

PaO2/FiO2 = ratio of partial pressure arterial oxygen and fraction of inspired oxygen * Pack-years are the number of cigarette packs smoked per day multiplied by the number of years smoking. The original ZDS comprises five extended donor criteria and five comorbidities. The adapted version of the score has been limited to four extended donor criteria (see methods section for details).

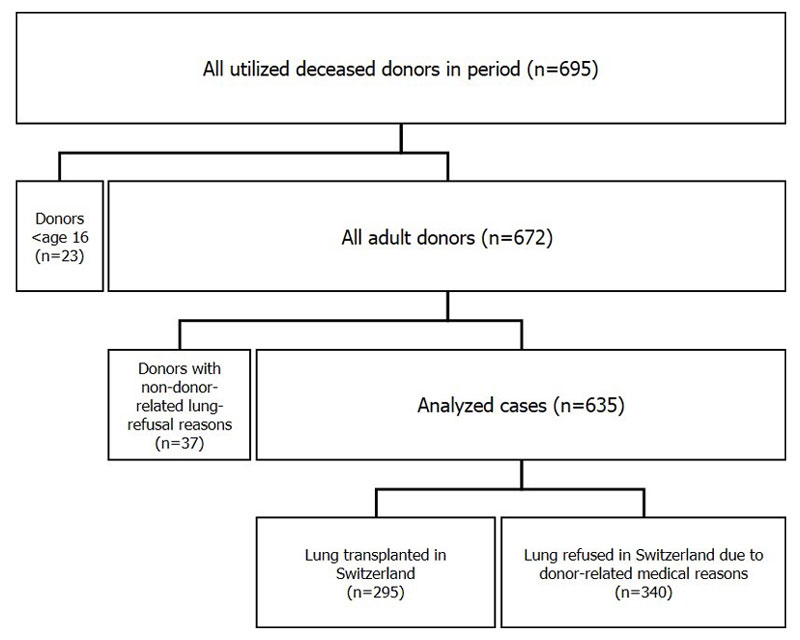

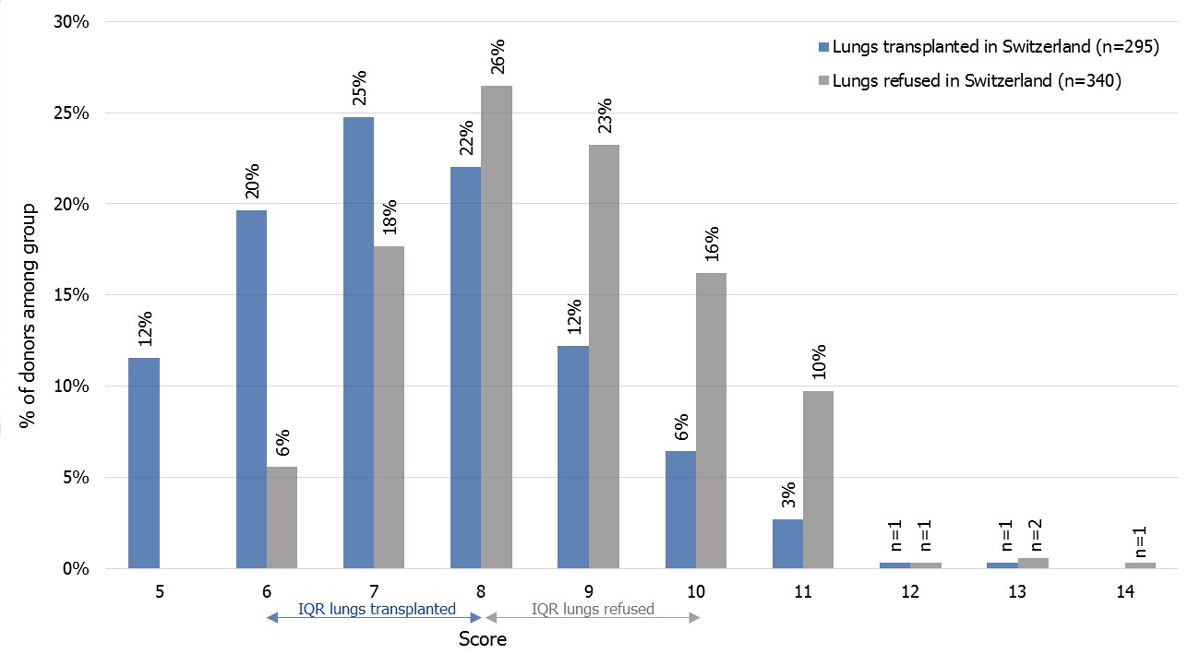

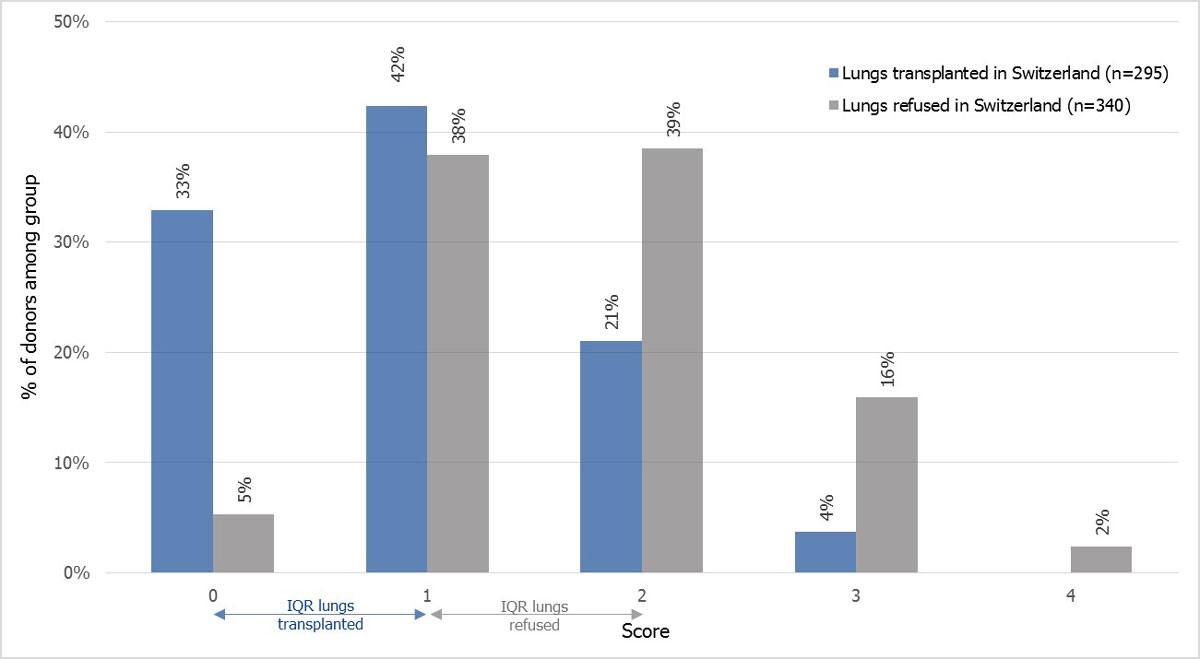

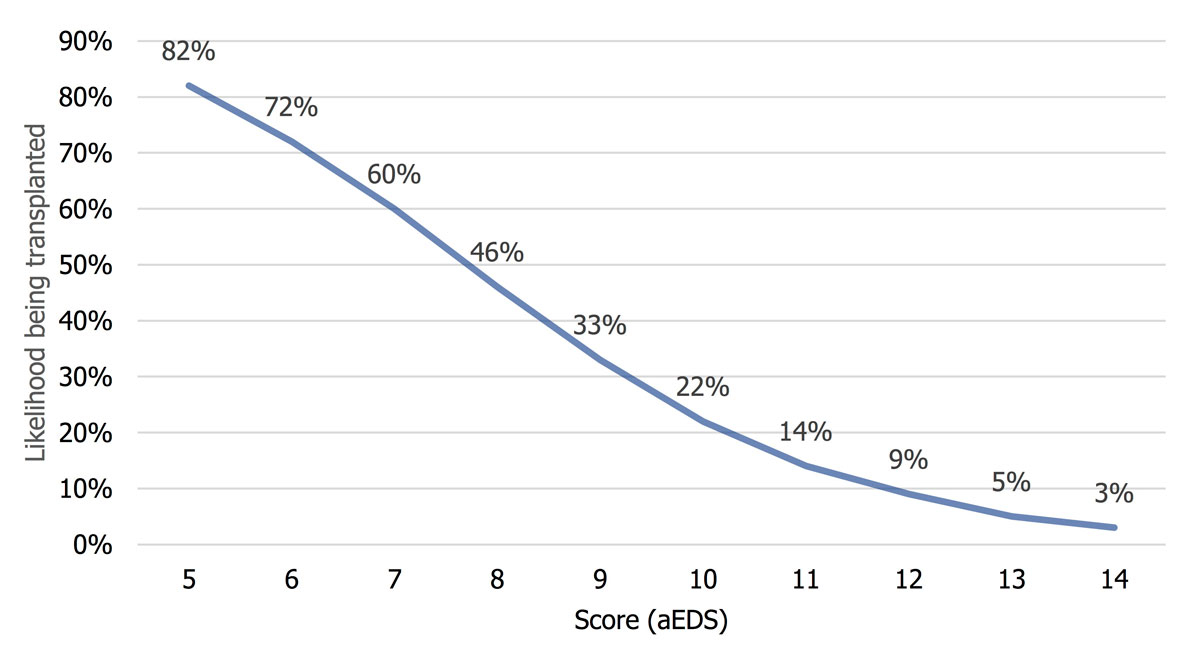

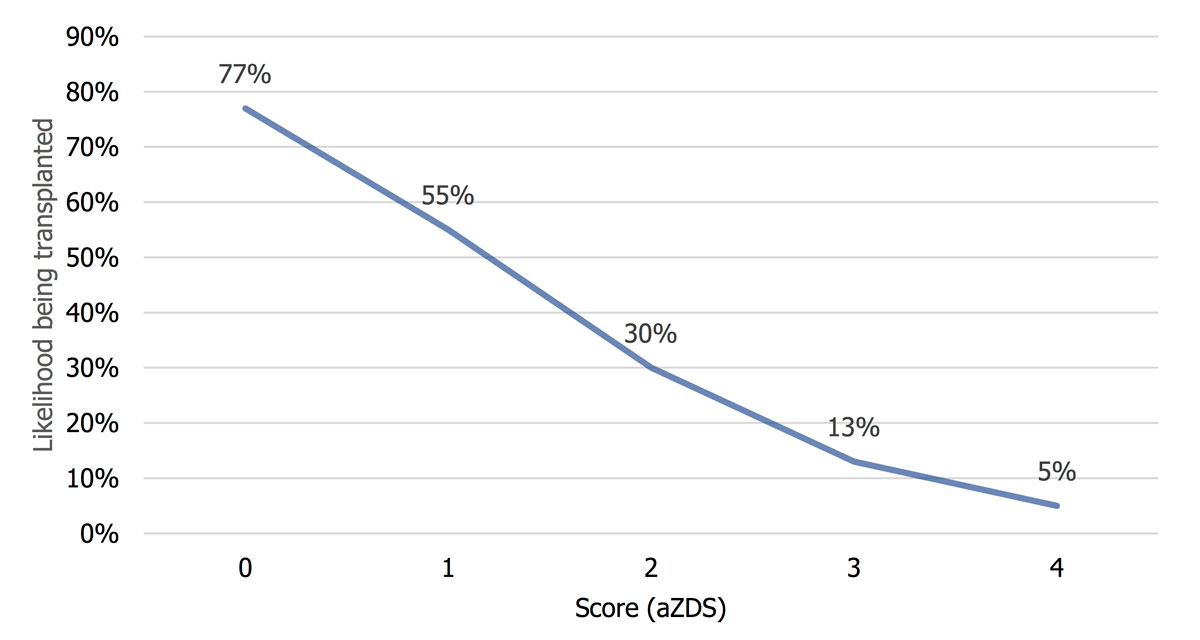

The frequency distribution of adapted score values for lungs transplanted versus refused is shown in figure 2 for aEDS, and in figure 3 for aZDS. Whether the adapted scores can predict whether a donor lung is accepted or refused in Switzerland was evaluated using logistic regression. We found that this held true for both scores: As the score of a donor increased, the odds of the lung being transplanted in Switzerland significantly decreased. This effect was slightly more pronounced with the aZDS than with the aEDS. Detailed results of both logistic regression models are shown in table 4.

Figure 2 Adapted Eurotransplant donor score frequency distribution for accepted lung donors (blue) vs refused lung donors (grey). Arrows show the interquartile ranges (IQRs) of the score distribution of each group.

Figure 3 Adapted Zurich donor score for accepted lung donors (blue) vs refused lung donors (grey). Arrows show the interquartile ranges (IQRs) of the score distribution of each group.

Table 4 Results of two independent binary logistic regression models including the adapted Eurotransplant donor score (aEDS) and adapted Zurich donor score (aZDS), each as a single predictor for being transplanted in Switzerland.

| B (SE) | p-value |

Odds ratio

(95% CI) |

R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 (lung transplanted ~ aEDS) | −0.55 (0.06) | <0.001 | 0.58 (0.51–0.65) | 0.11 |

| Model 2 (lung transplanted ~ aZDS) | −1.04 (0.11) | <0.001 | 0.35 (0.28–0.43) | 0.13 |

R2 = McFadden

Based on the logistic regression models, expected probabilities for each score value were calculated. The probability of a lung being transplanted from a donor with an aEDS of five (best score) was 82%, whereas from a donor with an aEDS of fourteen (worst score) this probability was 3%. The probability of a lung being transplanted from a donor with an aZDS of zero (best score) was 77%, whereas for a donor with an aZDS of four (worst score) this probability was 5%. Expected probabilities are presented by score values in figure 4 (aEDS) and figure 5 (aZDS).

Figure 4 Probability of a donor lung being transplanted in Switzerland according to adapted Eurotransplant donor score (aEDS), based on a logistic regression model.

Figure 5 Probability of a donor lung being transplanted in Switzerland according to adapted Zurich donor score (aZDS), based on a logistic regression model.

The discriminatory power of the scores using the AUC was 0.719 (95% CI 0.680–0.758) for aEDS and 0.723 (95% CI 0.681–0.760) for aZDS, which for both was deemed a fair discrimination (interpretation of AUC values see methods section).

We evaluated two established scoring systems for the quality assessment of donor lungs by analysing Swiss organ donor data from 1 July 2007 until 30 June 2014. We found that both scoring systems (adapted to data available) were able to predict which donors are likely to be accepted for transplantation in Switzerland. The higher a particular donor “scores”, the more likely it is that the lung will be refused by the Swiss lung transplant centres. This finding basically holds true for both centres. A preliminary analysis showed a similar score distribution of transplanted and refused donors in both lung transplant centres. Therefore, the results of the preliminary analysis suggested that donor assessment and selection was carried out according to very similar criteria, yielding a donor selection that was similar over the entire study period. Thus, our study was designed to analyse national data and not to compare the two Swiss lung transplant centres.

Interestingly, the aZDS, which includes only four criteria selected solely on the basis of expert opinion, has as much discriminative power as the aEDS, which includes five criteria selected on the basis of results of a detailed statistical analysis (the discriminative power of aZDS was even found to be slightly higher than the one of aEDS even though not significantly). In other words, the aZDS may lack a statistics-based methodology compared with the aEDS, but transplant teams could apply both scores equally in their assessment of donor quality, with the aZDS being easier and faster to calculate.

However, according to our interpretation of the AUC values, the discriminative power of both scores was rather fair than good – and was definitely far from excellent. In practice, donors with high score values were transplanted, and others with low score values were refused. Particularly, donors with score values in the mid-range of the score distribution (e.g., donors with an aEDS of eight or an aZDS of one) are almost as likely to be transplanted as refused. This result, however, is not unexpected. There are numerous criteria that possibly can affect organ quality, and the criteria that build the scores are only a few of them. Also, organ quality is usually only one aspect considered in transplantation. The expert’s decision as to whether a particular donor lung is accepted or refused is always taken in the specific context of the recipient. In our analysis we included only donor-related refusal reasons as they were documented in the SOAS. However, in practice when a donor is refused, unambiguous designation of the refusal reason as donor-related or recipient-related is sometimes difficult. Additionally, and as also acknowledged by Smits and colleagues [7], these scores are derived from preprocurement values and therefore do not account for results of the physical examination of the lung at the time of retrieval.

Policymakers in Switzerland urge a national benchmarking system between different transplant centres. In order to optimise objectiveness, such a system would need to consider all risk factors that may influence the transplant outcome and would have to adjust for these risks as effectively as possible. To develop a risk-adjusted benchmarking system, it is essential to identify donor and recipient factors that possibly impact the centres’ outcome data. A donor quality scoring system that includes the most prominent donor risk factors for compromised graft function could possibly help facilitate risk adjustment of post-transplant outcome analyses, at least on the donor side. However, it is important to point out that the adapted donor quality scores evaluated in this study do not qualify for comparative outcome analyses since they have not been validated with recipients’ outcome data.

Instead, use of the scores could possibly support experts in their assessment of donor quality by providing them with a quantitative measure based on their own perceived risk from past practice. However, whether a potential donor organ should be accepted or refused for a particular recipient can only be decided after consideration of all the case-specific circumstances. Nevertheless, a donor risk score might also help to choose the right donor for the right recipient when the risk of an adverse transplant outcome and the risk of dying on the waiting list must be gauged.

A straightforward international comparison on the basis of the EDS is not feasible as we had to use an adapted version of the score. However, the overall lung acceptance rate by the two Swiss lung transplant centres was relatively high (46% over the entire study period). For comparison, acceptance rates in 2014 for donor lungs were 41% in Germany, 23% in the USA, 21% in France and only 9% in Italy [12]. Although these are remarkable differences, no comparative studies aiming to explain them are available in the literature according to the authors’ knowledge. In a Belgian study of extended-criteria donor lung donors, the authors stated that, worldwide, only 15–25% of all multiorgan donors have lungs suitable for lung transplantation because of serious injury following cardiopulmonary resuscitation, lung contusion, airway aspiration and pulmonary infection at the time of brain insult, as well as underlying lung disease [13]. In the same publication, a lung acceptance rate in the Belgian transplant network of around 40% for 2012 was reported, which is fairly similar to Switzerland. The authors partly explain this number by the density of hospitals in their country, which allows the procurement team to drive to all hospitals by car within 2 hours to check the quality of the donor lung on site.

Other possible factors potentially influencing acceptance practice may be waiting list composition, allocation modalities, and national or individual centre guidelines. It is important to note that the lung allocation modality in Switzerland incorporates no medical preselection by Swisstransplant. In other words, all donor lungs offered are made available to the transplant centres and, therefore, the acceptance rate we report directly represents the centres’ practices. Another possible explanation for the relatively high lung acceptance rate may be that Switzerland has a rather low organ donation rate [14], but also an excellent healthcare system. Owing to the low donation rate, there is a great imbalance between supply (organs donated for transplantation) and demand (patients on the waiting list). This imbalance may lead to a higher overall acceptance of grafts, as the pressure to meet the needs of patients awaiting transplantation may be higher. It is noticeable in this context that Switzerland and Germany share both a relatively low organ donation rate and a relatively high lung acceptance rate.

Whatever the reasons for the relatively high lung acceptance rate in Switzerland may be, it is of particular interest since some of the most important characteristics of Swiss lung donors considered relevant for graft function (e.g., age, history of smoking) are rather far from what is generally regarded as ideal. Seventeen percent of accepted Swiss lung donors in the study period were 65 years or older, whereas only 10% of European (data for 2015/2016), and only 1% of US lung donors were in the same age group [15, 16]. The percentage of US lung donors with a smoking history of 20 pack-years or more has more than halved since 2004, being as low as 10% on average during our study period (2007–2014) [17]. Our data show that the percentage of Swiss lung donors with a reported smoking history of 20 pack-years or more was on average 21% − more than twice as high as in the US.

The international comparison of donor characteristics and acceptance rates suggests that the relatively high yield of donor lungs in Switzerland (46% transplanted) may be a result of an extensive use of extended-criteria donors. This raises the question of whether the relatively frequent use of “non-ideal” donors in Switzerland poses additional risks to Swiss lung recipients. However, if one compares Swiss lung post-transplantation outcome data (not part of this study) with international outcome data, the answer to this question is no. Overall mortality of Swiss lung transplant recipients is very similar to available European data, being 26.4% in Switzerland, and 27.7% in Europe at 3-years post-transplant [18, 19]. The 1-year post-transplant mortality in Switzerland is even lower than the European average, 11.7 and 16.9%, respectively [18, 19].

Our study has several limitations, which are mainly related to data availability. The attempt to apply the original EDS on Swiss donor data showed that it is not straightforward to use a scoring system that includes results of complex clinical tests, and that was developed elsewhere. In reality, clinical examinations often follow different guidelines and procedures, and therefore vary from country to country, sometimes even between centres. Also, how the data are captured can vary depending on the instruments and computer software in use. In addition to that, the interpretation of some clinical examinations (such as x-ray or bronchoscopy) is to some extent subjective. In our study, it was not possible to use the original EDS because data capture in the Swiss transplantation programme was not of the same as Eurotransplant’s for some of the clinical criteria. Eurotransplant was confronted with the same issue when they tried to evaluate the Oto Score – indeed, it was the lack of detailed data needed for the calculation of the Oto Score that led them to develop their own scoring system, based on their available data [7].

It was the aim of our study to evaluate two established lung donor scores and not to develop a national score de novo. According to our analysis of donor baseline characteristics (table 1) there are several criteria that differ significantly between accepted and refused lung donors and are not included in either of the scores (body mass index, some specific causes of admission and death, some comorbidities). The criterion cancer is included in the aEDS, but we found no significant difference between accepted and refused lung donors. Thus, based on our results for Switzerland, the scores could be improved by incorporating more of the criteria that show significant differences, and by removing criteria which are not significantly different between transplanted and refused lung donors. Alternatively, donor or organ characteristics could be tested stepwise in a multivariate logistic regression model. Hence one could theoretically also derive a distinct Swiss lung donor quality score using a similar methodology as described by Smits et al. [7]. However, a new score would need careful validation by application to an independent cohort, and ideally by evaluating its predictive value for post-transplantation outcome (graft failure, patient survival). Such outcome analyses would need to control for a number of factors that probably also have a major impact on the post-transplantation outcome, such as ischaemia time, surgical aspects, and recipient selection criteria and medical condition at the time of transplantation.

The scores evaluated in this study are able to predict the likelihood that a donor lung is deemed transplantable by Swiss experts in lung transplantation. However, applying scoring systems that were developed from single-centre data or abroad to a national level requires careful adaptation to available data prior to their use in clinical practice.

As an alternative to adapting established scores, our analysis of donor characteristics could also serve as a basis for the derivation of a national quality score de novo. Such a new score would need to be validated on an independent sample and ideally tested for its predictive value in terms of post-transplantation outcome. Further studies could focus on outcome by including not only donor criteria but also ischaemia time, surgical aspects and the medical situation of the recipient at time of transplantation. A multivariate analysis of these factors may be of interest.

Donor lung utility in Switzerland is high compared with most other European countries or the USA despite a relatively low average organ quality in the Swiss lung donor pool. Yet, post-transplantation outcomes are overall comparable to other countries, which emphasizes the excellent quality of care of the Swiss lung transplant programme.

The authors would like to thank Marie Roumet and Moana Mika for their help with the statistical analysis.

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

1European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines. Guide to the quality and safety of organs for transplantation. 6th ed. S.l.: COUNCIL OF EUROPE; 2016.

2 Chaney J , Suzuki Y , Cantu E, 3rd , van Berkel V . Lung donor selection criteria. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6(8):1032–8.

3 Sommer W , Kühn C , Tudorache I , Avsar M , Gottlieb J , Boethig D , et al. Extended criteria donor lungs and clinical outcome: results of an alternative allocation algorithm. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32(11):1065–72. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2013.06.021

4 Botha P . Extended donor criteria in lung transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2009;14(2):206–10. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/MOT.0b013e328326c834

5 Van Raemdonck D , Neyrinck A , Verleden GM , Dupont L , Coosemans W , Decaluwé H , et al. Lung donor selection and management. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(1):28–38. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1513/pats.200808-098GO

6 Orens JB , Boehler A , de Perrot M , Estenne M , Glanville AR , Keshavjee S , et al., Pulmonary Council, International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. A review of lung transplant donor acceptability criteria. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22(11):1183–200. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-2498(03)00096-2

7 Smits JM , van der Bij W , Van Raemdonck D , de Vries E , Rahmel A , Laufer G , et al. Defining an extended criteria donor lung: an empirical approach based on the Eurotransplant experience. Transpl Int. 2011;24(4):393–400. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1432-2277.2010.01207.x

8 Inci I , Ehrsam J , Hillinger S , Opitz I , Schneiter D , Benden C , et al. The impact of donor comorbidities in predicting long-term survival in lung transplantation: the Zurich Donor Score. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2015;21(suppl1):S35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/icvts/ivv204.126

9 Oto T , Levvey BJ , Whitford H , Griffiths AP , Kotsimbos T , Williams TJ , et al. Feasibility and utility of a lung donor score: correlation with early post-transplant outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(1):257–63. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.07.040

10 Swets JA . Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science. 1988;240(4857):1285–93. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615

11R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. [Internet]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2017. Available from: https://www.R-project.org/

12Council of Europe. International figures on donation and transplantation 2014. Newsl Transpl [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2016 Jul 28];20. Available from: https://www.edqm.eu/sites/default/files/newsletter_transplant_2015.pdf

13 Somers J , Ruttens D , Verleden SE , Cox B , Stanzi A , Vandermeulen E , et al. A decade of extended-criteria lung donors in a single center: was it justified? Transpl Int. 2015;28(2):170–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/tri.12470

14 Weiss J , Elmer A , Mahíllo B , Avsec D , Cozzi E , Haase-Kromwijk BJJM , et al. Evolution of deceased organ donation activity vs. efficiency over a 15 year period: an international comparison. TPA-2017-1604R1 [Preprint, revised 2018 Feb 1].

15ISHLT. Characteristics for transplants performed between january 1, 2015 and december 31, 2016 [Internet]. ISHLT Transplant Registry Quarterly Reports for Lung in Europe. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.ishlt.org/registries/quarterlyDataReportResults.asp?organ=LU&rptType=donor_demo&continent=3

16OPTN. Deceased donors recovered in the U.S. by donor age [Internet]. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/view-data-reports/national-data/

17 Valapour M , Skeans MA , Smith JM , Edwards LB , Cherikh WS , Callahan ER , et al. OPTN/SRTR annual data report 2014: lung. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(S2, Suppl 2):141–68. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13671

18Koller MT, Stampf S, Rick J, Bianco S, Branca S, Achermann R, et al. Swiss Transplant Cohort Study report (May 2008 - December 2015) [Internet]. Basel; 2016 Aug [cited 2016 Nov 1] p. 76. (STCS Report). Available from: http://www.stcs.ch/internal/reports/stcs_annualreport_august_2016_final.pdf

19ISHLT. Survival rates for transplants performed between july 1, 2012 and june 30, 2016 [Internet]. ISHLT Transplant Registry Quarterly Reports for Lung in Europe. 2017 [cited 2017 Aug 29]. Available from: https://www.ishlt.org/registries/quarterlyDataReportResults.asp?organ=LU&rptType=tx_p_surv&continent=3

No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.