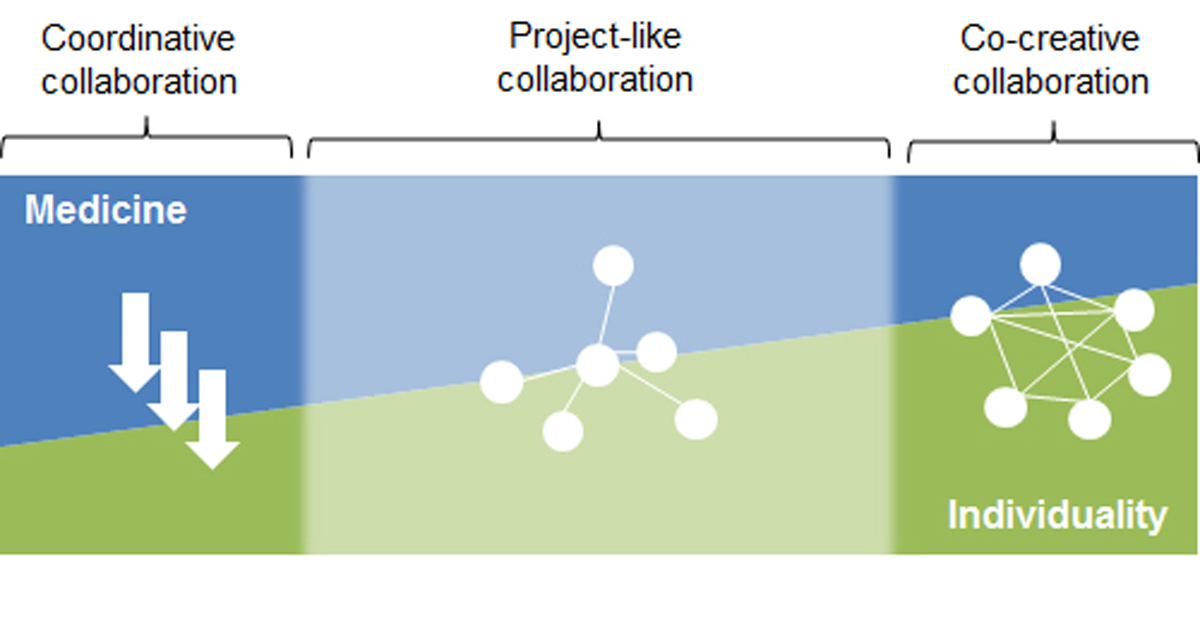

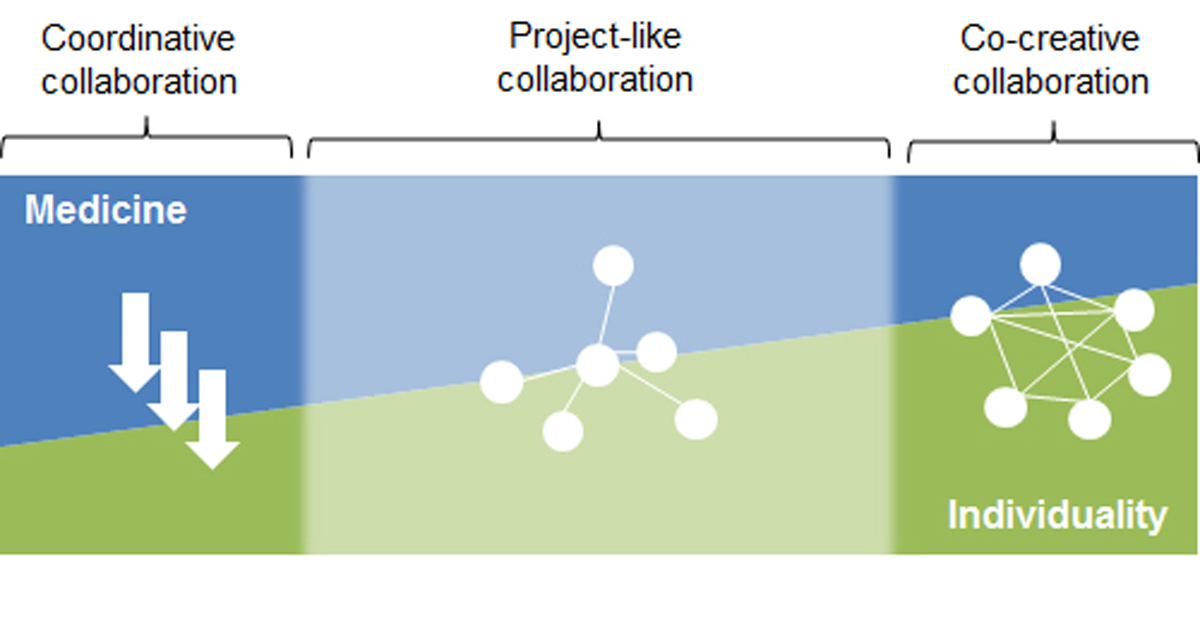

Figure 1 The spectrum, the three forms of interprofessional collaboration and the three corresponding modes of organisation (programme, hub, network). Adapted from Mintzberg and Glouberman (2001) [14].

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14525

Health system actors and observers are in agreement as to the importance and desirability of interprofessional collaboration (IPC) between healthcare professionals (nurses, physicians, physiotherapists, pharmacists, etc.). Enhanced IPC has long been seen as a path to higher quality and lower spending in health care and as an opportunity “to equalize power relations among health practitioners” [1]. Despite these widely accepted beliefs, the term IPC is still relatively new. For a long time, the concept of professionalism was reserved for the traditional professions (physicians, theologians, attorneys) [2, 3]. Since the 1960s, a progressive extension of the term IPC, involving several different professions in general as in health care, may have been noted [4]. During this shift in focus from professionalism to interprofessionalism, not only the relevance of non-medical and of nursing competencies in particular, but also the necessity of consistent negotiation and coordination processes between the different professions, became evident. Against this background, it is obvious that IPC has gained increasing attention during recent years.

This development is reflected in the emergence of a bewildering variety of definitions of IPC to be found in the literature. For IPC in health care there is an extensive, but highly disparate literature available: in a 2017 updated systematic Cochrane review, only nine studies (2009: five) met the inclusion criteria of assessing the impact of practice-based interventions designed to change IPC and were included in the meta-analysis [5]. It is therefore not astonishing that the authors conclude “that there is not sufficient evidence to draw clear conclusions on the effects of IPC interventions”.

A discourse analysis exploring 188 articles on IPC published from 1960 to 2011 is enlightening [6]. The most important insight from this analysis is, as the authors state, “that, over the last 50 years, the term ‘interprofessional collaboration’ has not signified the same thing to all who use and apply the term”. In particular, this meta-analysis has shown that academic discourse on IPC comprises two major strands: a utilitarian discourse, primarily concerned with the gains in efficiency and improved outcomes that can be achieved through increased collaboration between different professional groups in healthcare, and an emancipatory discourse, largely devoted to ways of overcoming the dominance of a single (e.g., medical) profession over others (e.g,. nursing professionals) and placing interprofessional power relations on a more equal footing. It is thus not surprising that IPC is also used as a political concept, or even, in certain contexts, as a battle cry. It also serves as an instrument for articulating interests, defining positions and highlighting the need for action.

In the present survey, we therefore eschewed an ex ante definition of IPC and instead set ourselves the goal of reconstructing what IPC means in the practice of health professionals – also because this practice may contrast with theoretical and normative conceptions of IPC [7].

The fundamental objective of the study was to explore, in five different settings (primary care, surgical care, internal medicine, psychiatric care and palliative care), what is described by practitioners as successful or unsuccessful IPC and, from this, to derive strategies for improving collaboration between health professionals. The selection of these settings was intended to give a broad bandwidth of the reality of Swiss health care. These settings should not be confused with medical disciplines, but should instead be understood as methodical modelling of different patterns of interprofessional interactions. The study was based on a total of 25 qualitative, narrative interviews conducted with members of different professional groups in the five settings mentioned above. Of these, 5 interviews were conducted in university hospitals, 14 in non-university hospitals and 6 in outpatient contexts. Of the 25 interviews, 20 were in German and 5 in French. As interviewees, we invited physicians (10), nurses (10), clinical psychologists (2), occupational therapists (2) and one physiotherapist (table 1). There was no refusal to participate in our interviews. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and subjected to an in-depth analysis in a multi-stage evaluation process based on the principles of the Grounded Theory [8–12]. The material was analysed in three circular steps. First, the material was scanned for descriptions of IPC. Second, these unsorted narrations were searched for recurrent patterns. The result was the construction of core categories. Third, we identified categories especially relevant regarding the SAMW-Charta and reanalysed the material in several data workshops.

Table 1 Overview settings and interviewees.

| Physicians | Nurses | Other | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical care | 3 | 2 | – |

| Internal medicine | 3 | 3 | – |

| Psychiatric care | 1 | 1 | 1 psychologist 1 occupational therapist |

| Palliative care | 1 | 2 | 1 psychologist 1 occupational therapist |

| Primary care | 2 | 2 | 1 physiotherapist |

Methodologically, the focus on successful examples implies an exploration of positive variations reinforced by contrasts with negative variations. An analysis of this kind makes it possible to identify factors that, from the perspective of the health professionals interviewed, are central to IPC.

A main finding of our study is that what were described by professionals as examples of successful IPC may be identified as three distinct modes of collaboration between different professions:

Another finding emerging from the interviewees’ narrations was the extent to which either medicine – on the basis of professional self-conceptions and skills – holds interpretive authority or the individuality of the patient, but also the specific expertise and individuality of the various health professionals concerned, comes into play or even predominates. Therefore, we propose a continuum between a medically driven collaboration (blue area in fig. 1) at one end of the spectrum and a collaboration driven by the individuality of the patients as well as of the healthcare professionals at the other end of the spectrum (green area in fig. 1). Two diametrically opposed examples are resuscitation and palliative care: in the former case, collaboration follows the logic of medical action, whereas in the latter it is structured by multidimensional processes of negotiation between the patient’s perspective and values and the various professional perspectives. Evidently, the relationship between these two dimensions can vary: this can be represented schematically as a continuum, with the relative proportions increasing or decreasing.

Figure 1 The spectrum, the three forms of interprofessional collaboration and the three corresponding modes of organisation (programme, hub, network). Adapted from Mintzberg and Glouberman (2001) [14].

In addition, the examples of IPC described involve three distinct modes of organisation, or ways in which actions are coordinated: a clearly ordered, structured combination/sequence of different skills and responsibilities (“programme”); flexible recourse to various professional skills, guided by a central “hub”; and a “network” in which the various skills are organised interactively [14, 15].

The three forms of collaboration, the medicine/individuality ratio and the corresponding modes of organisation (programme, hub, network) are summarised in a heuristic diagram (fig. 1).

The interviewees’ narrations provided striking evidence that the question of whether and how IPC occurs, and is perceived by the participants as successful or unsuccessful, strongly depends on the contexts or settings in which these health professionals work. This is an interesting finding, since it could also be (and indeed has been) assumed that IPC is driven by individuals, teams, education, profession or management and thus depends, respectively, on individual preferences, team dynamics, the type of education experienced, membership of a given profession, or the extent to which IPC has been defined as a goal by management. These factors certainly do influence the practice and perceptions of IPC. However, our results additionally show to what extent setting-specific structures are constitutive of both the practical implementation and the subjective perception of IPC.

Intensified IPC, according to the perceptions and narrations of the professionals interviewed, occurs primarily in response to patient “crises”. However, the types of “crisis” and the resultant forms of intensified IPC vary enormously: in acute somatic crises, for example, the coordination of the various professionals’ expertise follows a medical logic, whereas end-of-life crises in patients receiving palliative care give rise to individualised treatment pathways, without conforming to a single rationale.

Whereas these two forms of intensified IPC are associated with particular types of case or patient, the third – project-like collaboration – is less situation-specific. It involves ad hoc or more highly organised processes designed to improve the management of cases that require a number of different disciplines and professions. Project-like collaboration comes into play in cases where a weakly coordinated combination of complementary skills – the “norm” in healthcare – is felt to be inadequate. This form of collaboration varies widely and is found in diverse settings. Examples were observed in inpatient internal medicine, primary care or inpatient psychiatric care; they demonstrate that project-like collaboration is time-consuming and often precarious in environments where it is the exception rather than the rule.

Given that the form and the success of IPC are context-dependent, it seems appropriate to take a more nuanced view of standard measures to promote intensified IPC. Two points are immediately apparent. Firstly, indisputably – and this was emphasised by all interview partners – a constructive culture of cooperation and equal-footing relations between professional groups are key requirements for successful IPC; measures to promote such conditions are therefore appropriate. At the same time, the results of our study suggested that cultural change provides a necessary but not sufficient foundation for sustainable promotion of IPC. Equally crucial is recognition of, and adjustment to, the specific requirements of each setting, defined in organisational and professional terms.

Secondly, taking on board the experience of the professionals interviewed in the five settings, IPC is not to be equated with the (re-)allocation of responsibilities between professional groups, or with delegation and/or substitution. The shifting of responsibilities between professional groups, however appropriate this may be for various reasons, does not automatically involve the element of consolidation of processes and actions described above. It should be noted, however, that the discussion and implementation of such reallocations can provide excellent opportunities for IPC-related (cultural) reflection.

Given the rising complexity of treatments, the impending shortage of healthcare professionals and the upwards spiral of healthcare expenditure, the calls for more and better collaboration between the different professional groups are becoming louder in Switzerland. Against this background, different major initiatives have been taken recently in Switzerland, e.g. by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) or by the Swiss Office of Public Health (FOPH) [16].

The present survey was also intended to serve as a basis for recommendations as to how IPC could be fostered in Swiss health care. Given the diversity of forms of collaboration we have presented above, it becomes evident that there can be no single, universally applicable recommendation that would promote intensified IPC in all the various areas and clinical settings. Rather, there is a need to consider the requirements and possibilities for each particular form of collaboration. We therefore propose different options for action at the macro-, meso- and micro-level with the aim to establish common ground for further discussions on IPC.

The concept of IPC is often invoked in cases where attention is to be drawn to existing shortcomings, in order to strengthen one’s own position and/or to highlight unsatisfactory working conditions and/or results. Here, as a political and politicisable idea, IPC can assume an important indicator function.

Successful IPC was primarily described as an “island” of intensified collaboration, which is typically of a temporary or project-like nature and is thus dependent on instruments for institutionalisation. These can take the form of structures, tools or so-called boundary objects [17]. What these all have in common is that they can be part of different social worlds (e.g. professional groups) and help to integrate and promote interaction between them. According to our study, interprofessional organisational structures such as boards or ethics committees have proved to be indispensable especially where the health professionals concerned are confronted with the demands of both coordinative collaboration (typically involving time pressure) and co-creative collaboration (requiring a significant investment of time). By enabling the reconciliation of these demands, such structures serve as an important instrument for improving IPC.

At the individual level, awareness should be raised, in particular of the social, structural and cultural dynamics characterising IPC in the health system; this is a prerequisite for a constructive approach to the topic.

The study was supported by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences.

1 Dingwall R . Accomplishing Profession. Sociol Rev. 1976;24(2):331–50. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1976.tb00116.x

2Stichweh R. Professionen in einer funktional differenzierten Gesellschaft, in: Combe A, Helsper W (Hg.): Pädagogische Professionalität. Untersuchungen zum Typus pädagogischen Handelns. Frankfurt a. M: Suhrkamp/Insel; 1996. pp 4969

3Atzeni G. Professionelles Erwartungsmanagement. Zur soziologischen Bedeutung der Sozialfigur Arzt. Baden-Baden: Nomos; 2016

4 Corwin R . The Professional Employee: A Study of Conflict in Nursing Roles. Am J Sociol. 1961;66(6):604–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1086/223010

5 Reeves S , Pelone F , Harrison R , Goldman J , Zwarenstein M . Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD000072.

6 Haddara W , Lingard L . Are we all on the same page? A discourse analysis of interprofessional collaboration. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1509–15. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a31893

7World Health Organization. A Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education & Practice. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

8Glaser B, Strauss A. Grounded Theory, Strategien qualitativer Forschung, Göttingen: Huber; 1998

9Strübing J. Grounded Theory. Zur sozialtheoretischen und epistemologischen Fundierung des Verfahrens der empirisch begründeten Theoriebildung. Wiesbaden: Springer VS; 2008

10 Nassehi A , Saake I . Kontingenz: Methodisch verhindert oder beobachtet? Ein Beitrag zur Methodologie der qualitativen Sozialforschung. Z Soziol. 2002;31(1):66–84.

11 Nassehi A , Saake I . Begriffsumstellungen und ihre Folgen – Antwort auf die Replik von Hirschauer/Bergmann. Z Soziol. 2002;31(3):337–43.

12 Vogd W . Systemtheorie und Methode? Zum komplexen Verhältnis von Theoriearbeit und Empirie in der Organisationsforschung. Soziale Systeme. 2009;5(1):97–136.

13 Weick K , Roberts K . Collective Mind in Organizations. Heedful Interrelating on Flight Desks. Adm Sci Q. 1993;38(3):357–81. doi:.https://doi.org/10.2307/2393372

14 Glouberman S , Mintzberg H . Managing the care of health and the cure of disease--Part II: Integration. Health Care Manage Rev. 2001;26(1):70–84, discussion 87–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1097/00004010-200101000-00007

15Mintzberg H. The Structuring of Organizations. Basingstoke: Macmillan; 1979

16Schweizer Akademie der Medizinischen Wissenschaften. Charta: Zusammenarbeit der Fachleute im Gesundheitswesen. Basel: SAMW; 2014.

17 Star SL , Griesemer JR . Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907-39. Soc Stud Sci. 1989;19(3):387–420. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

18 Huber M , Koch S , Hund-Georgiadis M , Mäder M , Borgwardt S , Stieglitz RD . Diagnostische Validität des Basler Vegetative State Assessments - BAVESTA. International Journal of Health Care Professions. 2014;1:50–60.

The study was supported by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences.