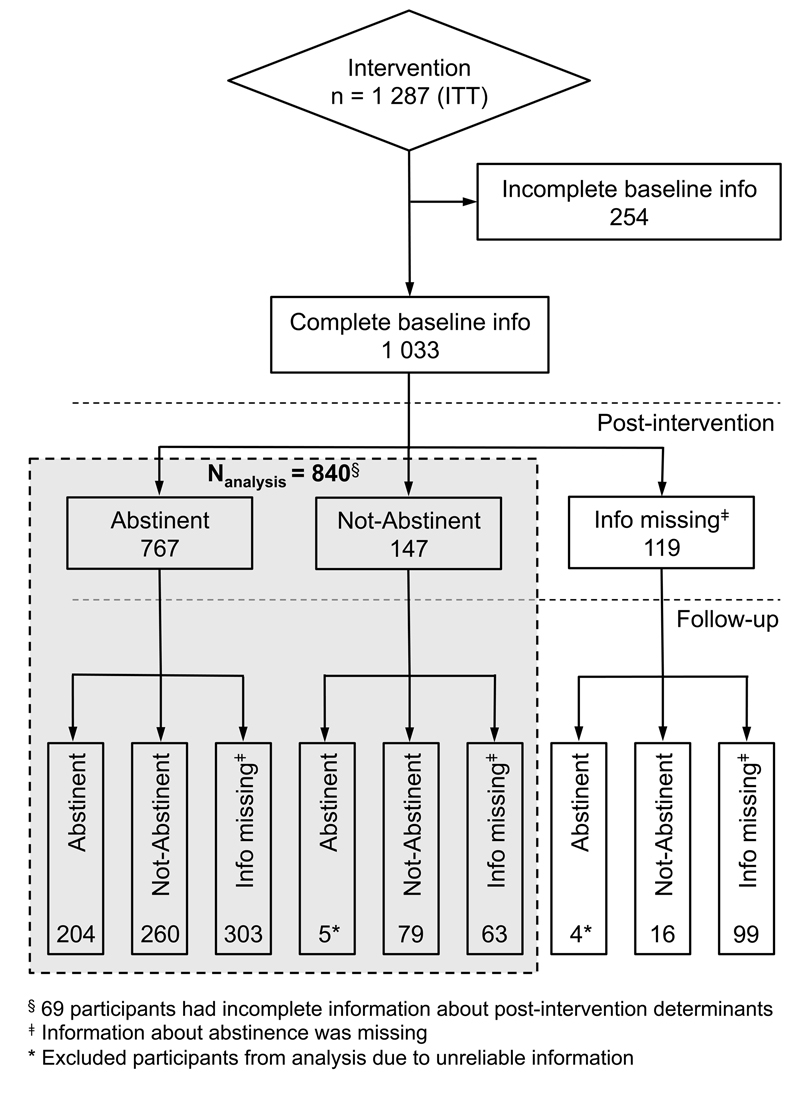

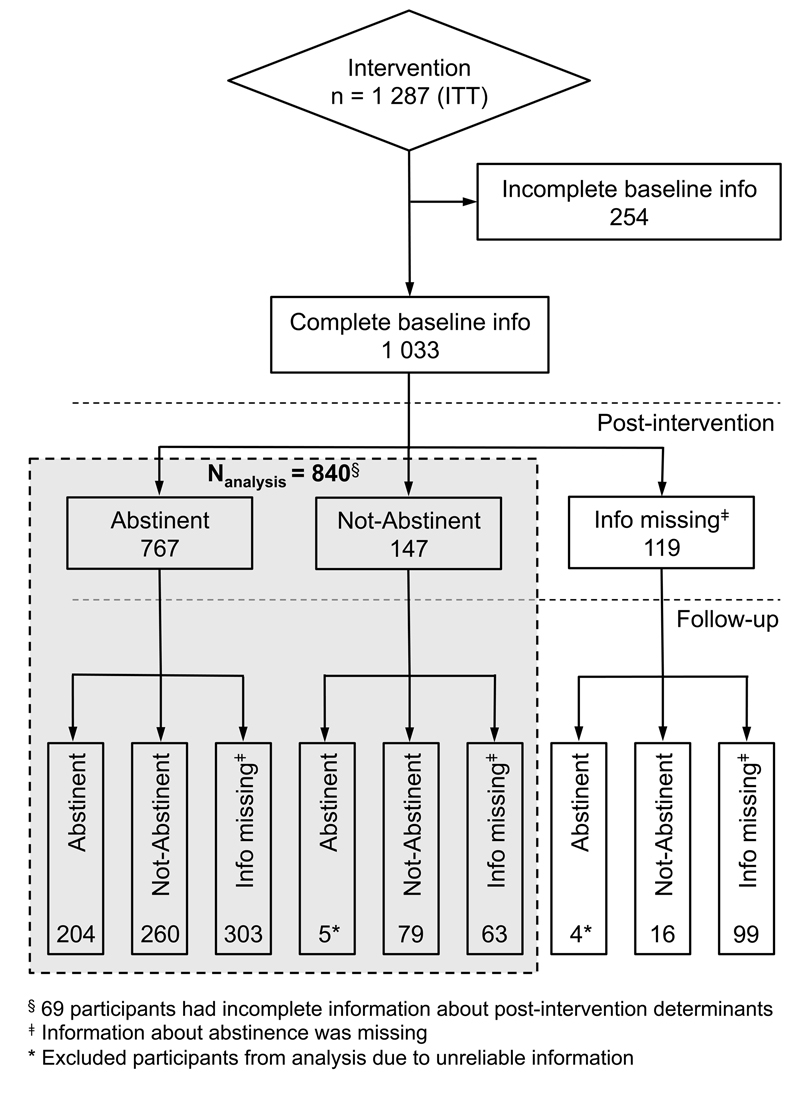

Figure 1 Flow chart of study participants

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14500

In 2012, 25.9% of the Swiss population above the age of 15 were smokers [1]. In Switzerland, smoking accounts for approximately 9000 deaths each year and for economic damage of up to 10 billion Swiss francs from medical treatment costs, losses in productivity and intangible costs (loss of quality of life, years of life lost) [2, 3]. Smoking cessation is associated with a reduction of total morbidity and mortality related to cardiovascular diseases, chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases and lung cancer [4].

Group behavioural therapy is considered effective for achieving long-term smoking abstinence and thereby preventing tobacco-related diseases [5, 6]. Group interventions might also be more cost-effective than more expensive interventions for single smokers, because of the better use of the trainers’ time [7]. Group interventions furthermore offer a setting of social learning and the possibility to share experiences, encourage and support each other, potentially increasing members' supportive social networks, which may contribute to satisfactory cessation rates [8, 9]. As most people spend about a third of their day at work, established communication channels in this setting can reach and encourage a large number of smokers to participate in a smoking cessation programme. Participants could also benefit from sustained peer group support and positive peer pressure within the company. Other advantages are the proximity of the training to the workplace and the opportunity for companies to support the health of their employees [10].

Shortly after Switzerland signed the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) in 2004, the Lung Association Basel launched the project “Enterprise Smoke-free” (“Unternehmen rauchfrei”), which supports companies interested in regulating smoking at their workplaces [11, 12]. A smoking cessation programme for a workplace setting was developed in collaboration with the Institute for Therapy Research (IFT) in Munich and implemented in the various language regions of Switzerland [13]. The programme was further strengthened in 2010, when a nationwide law that limits second-hand smoke exposure in most workspaces and public indoor areas was implemented [14].

Our hypothesis was that demographic and personal characteristics, as well as the social environment (e.g., family, friends, and co-workers), of the participants have a direct and indirect influence on their motivation to stop smoking and on short- or long-term abstinence failure. Additionally, we expected that some external factors, such as training, trainer and company characteristics, withdrawal symptoms and use of pharmacotherapy influence relapse rates.

The hypothesis was built in the light of the following evidence from cessation interventions different from ours. Demographic determinants such as gender, age, body mass index and work function (as a marker for education status) have been shown to be directly associated with abstinence failure [15–19]. Smoking characteristics known to influence smoking cessation include years of smoking, number of cigarettes smoked per day and time of first cigarette smoked after waking up [16, 20–22]. Motivation factors such as intention to stop smoking, previous smoking cessation attempts and incentives, including provision of costs or time for training by employer, were reported to have an impact on smoking relapse [23–26]. There are only a few studies describing the association between relapse rates and training characteristics such as training structure, group size and trainer gender [8, 27]. The effect of withdrawal symptoms and weight gain are well documented and have a significant impact on abstinence failure [28, 29]. Additionally, pharmacotherapy has been shown to help prevent smoking relapse [30].

The ultimate objective of this current analysis was to identify groups of smokers at increased risk of abstinence failure in this specific workplace-set intervention, who would benefit from additional support before or during training sessions.

This prospective cohort study was part of an evaluation programme mandated by the Swiss Tobacco Prevention Fund to assess accountability and quality of smoking cessation courses within the Enterprise Smoke-free programme.

The participants were contacted at their workplace through internal newsletters, intranet news, posters and flyers. Three anonymised questionnaires were distributed to participants: at the beginning of, the end of, and 12 months after the end of the training. To improve the response rate for the 1-year follow-up questionnaire, participants were reminded first with a letter, then by up to three phone calls and, more recently, also by e-mail.

All participants were informed, orally in the first session and again in writing at later time-points, about the scientific evaluation and confidential data handling. Participation in the programme was voluntary, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The joint ethics committee of northwest and central Switzerland (EKNZ) approved this study based on the evaluation data in April 2015.

Enterprise Smoke-free is a cognitive behavioural group therapy combined with up to three individual proactive telephone counselling calls of up to 10 minutes each. The structure and content of the programme is described in table 1. Enterprise Smoke-free is based on the commonly used multicomponent treatment programme, including a fixed quit day, social support, motivational enhancement, lifestyle changes, coping techniques for risk situations, and relapse prevention [31]. It was enhanced by elements from psycho-education, and change- and acceptance-oriented psychotherapy methods, including clarification of goals, imagination rehearsal, acceptance strategies, skills training, emotion regulation and stress tolerance [32, 33]. Pharmacotherapy was not a standard component of the cessation therapy, but its use was not actively discouraged.

Table 1 Training structure and content.

| Phase | Sessions | Methods | Content | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Standard

(6 weeks) |

Compact

(4 weeks) |

Super compact

(2 weeks) |

|||

| Preparation | Information event | Information about smoking and cessation programme. Motivating to participate. Offering decision support. |

|||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | Cognitive preparation, motivation, psycho-education | Quiz about smoking and non-smoking. Lecture on smoking, non-smoking and passive smoking. Self-monitoring of smoking behaviour. | |

| 2 | Motivation, reinforcing ambivalence, self-control | Collecting arguments pro-smoking and pro-smoke-free-living. Personal gain of smoke-free-living. |

|||

| 3 | 2 | Motivation, psycho-education, coping skills, behavioural alternatives to smoking | Lecture on the functioning of smoking in dependent smokers. Identification of smoking situations. Alternatives to smoking. Information on nicotine replacement. |

||

| Coping skills, self-management | Preparation for quit day. Lecture on strategies to cope with craving. | ||||

| Quit day | Stop smoking. | ||||

| Stabilisation | Proactive telephone counselling | Talking about individual situations. | |||

| 4 | 3 | 2 | Relapse prevention, positive reinforcement, psycho-education | Exchange of experiences. Lecture on lapse and relapse. Lecture on withdrawal symptoms. Rewards for smoke-free living. |

|

| 5 | |||||

| 6 | Relapse prevention, positive reinforcement, imagination | Exchange of experiences. Developing a non-smoker’s identity. Retrospection. Planning the smoke-free future. |

|||

| Proactive telephone counselling | Talking about individual situations. | ||||

Developed in collaboration with the Institute for Therapy Research (IFT).

On the basis of the standard programme (six weekly sessions of 90 minutes), compact (4 weeks, three sessions of 180 minutes) and super-compact (two weekly sessions of 270 minutes) versions were developed at the request of two big companies, for organisational reasons. Irrespective of programme type, a quit day is fixed in the middle of the programme. Training types differ in the number of sessions and time between quit day and end of the training, but not in their content or total contact time of 540 minutes.

Trainers were certified after attending an extensive standardised training seminar according to the IFT model. To maintain high training quality, highly structured manuals were distributed to the trainers and they have to attend an annual advanced training session [5].

The only incentive for participants to join the programme was the waiving of the training fee, offered by most companies. Only a few companies linked fee reimbursement to successful abstinence during the training.

Figure 1 shows the flow chart of study participants. All participants who voluntarily attended the Enterprise Smoke-free smoking cessation training at their workplace between 16 February 2006 and 25 September 2012 were included in this study. The study population therefore consisted of 1287 smokers aged 16 to 68 years.

Figure 1 Flow chart of study participants

Sociodemographic characteristics, smoking behaviour, motivation to quit, training and health data were taken from the questionnaires developed by the IFT and condensed for evaluation purpose by the Lung Association Basel and the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute Basel [5].

First, we identified the postintervention and 1-year quit rates as outcomes. The study sample used to describe the quit rate consisted of all 1287 participants. Abstinence was thereby defined in accordance with the Russell Standard defining criteria for the standard evaluation of abstinence rate of smoking cessation interventions [34]. The Russell Standard consists of: a follow-up for 6 or 12 months; self-reported abstinence allowing up to five cigarettes in total; biochemical verification of abstinence at follow-up; and use of an intention-to-treat approach in which data from the full sample of all smokers are included in the analysis unless they have died or moved to an untraceable address. According to the Russell Standard and in our study, nonabstinence was defined as self-reported nonabstinence for persons smoking more than five cigarettes in total since the quit day [34]. Dropouts from the training, nonresponders to the postintervention questionnaire, persons lost to follow-up, and persons who refused to participate in one of three evaluation questionnaires or had missing data on abstinence at the postintervention assessment and at 1-year follow-up were classified as nonabstinent at postintervention and after 1 year, respectively. This is a conservative approach to avoid overestimation of therapy benefits due to the higher likelihood of non-quitters being lost to follow-up. We also took into account a trichotomous outcome variable with levels “smoking abstinence”, “nonabstinence”, and “nonresponse at the 1-year follow-up” to specifically examine the reasons for nonabstinence or nonresponse.

Second, we investigated risk factors for nonabstinence from smoking at the postintervention assessment and at 1 year as outcomes. The study sample to investigate predictors of smoking relapse consisted of 840 participants only; 447 participants were excluded because of incomplete pre- and postintervention variables, missing information about postintervention abstinence, unreliable information about abstinence (declaration as not abstinent or information missing at postintervention but as abstinent at follow-up), and other inaccurate information.

The risk factors for nonabstinence were grouped into sociodemographic determinants, smoking determinants, motivational determinants and training determinants at baseline (see table 2 below for specific variables in these groups), as well as into health determinants and training determinants at postintervention (see table 3 for specific variables in these groups).

Among the sociodemographic determinants, the work function of the training group was used to classify participants into raw socioeconomic groups because of missing detailed information on education and income of the individual participants. Smoking determinants were selected and partly classified according to the Fagerström test for nicotine dependence [35]. The participants’ health characteristics were based on known nicotine withdrawal symptoms and weight gain as a main unfavourable health effect [29, 36].

Categorical data were described using absolute and relative frequencies and quantitative variables were summarised as mean and standard deviation. Wald tests were used to assess the statistical significance of estimates and to compare related estimates.

The association of smoking abstinence failure (nonabstinence) with a total of 39 variables was analysed using multilevel logistic regression models with random intercept for training courses. These large numbers of potential predictor variables were selected on the basis of the literature and available data, in order to minimise the risk of confounding of important effects and in order to find novel entry points of potential relevance to improve quit rates.

Analyses were conducted both with a dichotomous nonabstinence variable (with abstinence as reference group), including participants according to the intention-to-treat principle, and with a trichotomous nonabstinence variable distinguishing reported nonabstinence from lack of reporting. The trichotomous variable was analysed with multinomial logistic regression using “abstinence” as reference and adjusted for clustering within training courses by use of robust variance estimates. Models were built as follows. First, each of the variables was investigated for association with nonabstinence in minimally adjusted models, which were only adjusted for basic sociodemographic determinants (gender, age, work function, training language). Second, all variables were included in fully adjusted models. Five of the 39 variables had to be dropped from the models owing to collinearity problems (recommendation at postintervention; recommendation at 1-year follow-up; weight gain at postintervention; weight gain at 1-year follow-up; satisfaction with own collaboration).

Gender, age, training type and use of nicotine replacement or pharmacological therapy were a priori considered as effect modifiers as they are important potential targets for stratified adaption of smoking cessation interventions according to existing evidence. Strata-specific estimates according to gender, age, use of nicotine replacement and training type were obtained by letting the corresponding stratum variable interact with all other independent variables.

Associations were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs).A p-values <0.05 was considered statistically significant for main effects and <0.1 for interaction effects. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE 13.1 (Stata Corporation, TX, USA).

Overall, 1287 employees of 72 diverse companies participated in a total of 169 trainings given by 36 trainers. The costs of the smoking cessation training amounted to about 550 Swiss francs per participant [12].

Baseline characteristics of participants and trainings are presented in table 2, separately for (1) the intention-to-treat (ITT) sample (n = 1287), (2) the sample with complete information on relevant pre- and postintervention questions (n = 840; sample for studying determinants of quitting failure), and (3) the sample with incomplete information (n = 447). The identical grouping was used to show the postinterventional health characteristics and training opinion of participants in table 3.

Table 2 Baseline characteristics of participants and training in Enterprise Smoke-free, stratified by subsample of participants.

|

ITT sample

(all) n = 1287 |

Post-intervention sample

n = 840 |

Incomplete information sample

n = 447 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic determinants | |||

| Participant gender (female) | 540 (42.3) | 323 (38.5) | 217 (49.7) |

| Age (years) | 40.0 ± 10.7 | 39.4 ± 10.6 | 41.1 ± 10.9 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.8 ± 4.4 | 24.9 ± 4.1 | 24.6 ± 5.0 |

| Work function | |||

| Only employee | 545 (44.2) | 365 (43.5) | 180 (45.8) |

| Only management or with employee together | 409 (33.2) | 283 (33.7) | 126 (32.1) |

| Work function unknown | 279 (22.6) | 192 (22.9) | 87 (22.1) |

| Smoking determinants | |||

| Years smoked | 20.1 ± 10.4 | 19.8 ± 10.0 | 20.8 ± 11.1 |

| Cigarettes per day | 18.7 ± 8.1 | 18.4 ± 7.8 | 19.2 ± 8.6 |

| First cigarette after waking up (within 30 minutes) | 726 (58.6) | 484 (57.6) | 242 (60.9) |

| Motivation determinants | |||

| Intention to stop smoking (within 30 days) | 1064 (86.1) | 749 (89.2) | 315 (79.5) |

| Last smoke stop attempt (>1 year ago) | 694 (56.0) | 478 (56.9) | 216 (54.0) |

| Attended information event | 621 (54.2) | 440 (52.4) | 181 (59.2) |

| Attended all training sessions | 857 (76.9) | 675 (80.4) | 182 (66.2) |

| Costs paid (by company) | 1106 (88.5) | 759 (90.4) | 347 (84.6) |

| Time accounted (by participant) | 893 (71.2) | 594 (70.7) | 299 (72.0) |

| Training determinants | |||

| Training type (standard) | 721 (56.0) | 412 (49.0) | 309 (69.1) |

| Language (German) | 890 (69.2) | 552 (65.7) | 338 (75.6) |

| Season by training begin (winter) | 547 (42.5) | 341 (40.6) | 206 (46.1) |

| Group size | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 8.5 ± 2.6 |

| Trainer gender (female) | 864 (67.1) | 55.8 (66.4) | 306 (68.5) |

| Trainer and participant gender (same) | 619 (48.5) | 419 (49.9) | 200 (45.8) |

ITT = intention to treat Data are given as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Table 3 Health characteristics and opinion on training postintervention in Enterprise Smoke-free, stratified by subsample of participants.

|

ITT sample

(all) n = 1287 |

Post-intervention sample

n = 840 |

Incomplete information sample

n = 447 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Health determinants | |||

| Withdrawal symptoms postintervention | 1.9 ± 1.6 | 2.0 ± 1.6 | 1.7 ± 1.5 |

| Sleeping troubles | 234 (21.1) | 199 (23.7) | 35 (13.0) |

| Increased appetite | 493 (44.5) | 375 (44.6) | 118 (43.9) |

| Increased anxiety | 73 (6.6) | 58 (6.9) | 15 (5.6) |

| Increased irritability | 427 (38.5) | 339 (40.4) | 88 (32.7) |

| Difficulty concentrating | 171 (15.4) | 130 (15.5) | 41 (15.2) |

| Depressed mood | 184 (16.6) | 140 (16.7) | 44 (16.4) |

| Increased nervousness or agitation | 376 (33.9) | 299 (35.6) | 77 (28.6) |

| Slow heart beat | 42 (3.8) | 35 (4.2) | 7 (2.6) |

| Other withdrawal symptoms | 129 (11.6) | 103 (12.3) | 26 (9.7) |

| Weight gain postintervention | 421 (40.8) | 303 (38.1) | 118 (49.8) |

| Weight gain at 1-year follow-up | 325 (51.8) | 267 (53.0) | 58 (47.2) |

| Use of pharmacotherapy postintervention | |||

| None | 745 (67.1) | 577 (68.7) | 168 (62.2) |

| NRT only | 316 (28.5) | 227 (27.0) | 89 (33.0) |

| Supportive medications only | 34 (3.1) | 26 (3.1) | 8 (3.0) |

| NRT and supportive medications | 15 (1.4) | 10 (1.2) | 5 (1.9) |

| Training determinants | |||

| Comprehensibility trainer language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 5.8 ± 0.6 | 5.8 ± 0.7 | 5.9 ± 0.6 |

| Satisfaction (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | |||

| With trainer | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.7 | 5.4 ± 0.7 |

| With other participants | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 5.2 ± 0.8 |

| With own collaboration | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.0 |

| With training content | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.8 | 5.1 ± 0.9 |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped | 722 (67.0) | 582 (69.3) | 140 (59.1) |

| Recommendation postintervention | 1045 (95.7) | 795 (96.5) | 250 (93.3) |

| Recommendation at 1-year follow-up | 567 (91.7) | 455 (92.3) | 112 (89.6) |

ITT = intention to treat; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy Data are given as mean ± standard deviation or n (%).

Of all 1287 participants, exclusions were as follows: 19.7% (n = 254) due to incomplete preintervention information; 5.4% (n = 69) due to incomplete postintervention information; 9.2% (n = 119) due to missing information on postintervention abstinence, and 0.4% (n = 5) due to unreliable information on abstinence.

More men than women participated in this workplace-based smoking cessation training (57.7%, n = 737). Overall, 21.5% (n = 277) of all participants were younger than 30 years and 50.0% (n = 643) were older than 40 years. The level of nicotine dependence among participants was high, with 58.6% (n = 726) smoking their first cigarette within 30 minutes after waking up and an average of 18.7 cigarettes per day. The majority (95.3%, n = 1180) of the employees learned about the cessation training through company internal communication channels and 86.1% (n = 1064) were highly motivated to quit smoking. The postintervention and 12-month follow-up questionnaire response rates were 87.4% (n = 1 125) and 49.9% (n = 642), respectively.

The subsample of participants for analysing determinants of smoking cessation differed in several factors from the sample excluded because of missing information (tables 2 and 3 ).

At the end of the training (postintervention), the rate of self-reported abstinence was 83.4% (rate for all participants who answered the questionnaire) or 72.4% (according to an ITT approach: rate in full sample considering dropouts, non-responders and missing data on abstinence as nonabstinent); 14.4% of 1287 subjects actively reported failure to be abstinent; 13.2% of the sample did not respond to this question). One year after the training (1-year follow-up), the corresponding rates of self-reported abstinence were 37.4% and 18.6%, respectively (31.1% actively reported relapse; 50.3% did not respond to this question).

The 12-month abstinence rates associated with the standard (n = 721) and the compact or super-compact programme (n = 566) were similar (18.2% vs 19.1% according to an ITT approach).

Table 4 shows the results of the fully adjusted models including 34 independent predictors. Only the results for variables that were independently and statistically significantly (p <0.05) associated with either nonabstinence postintervention or after 1 year of follow-up are shown in this table (see supplementary tables S1A and S1B in appendix 1 for the full set of associations in minimally adjusted, fully adjusted and multinomial models). More and different factors were associated with nonabstinence at postintervention compared with the 1-year follow-up.

Table 4 Independent determinants of nonabstinence post-training and at 1-year follow-up.

| Determinants (reference group) | Postintervention | 1-year follow-up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonabstinence vs abstinence | Nonabstinence vs abstinence | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Participant gender male (female) | 0.68 | 0.40–1.14 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.63–1.43 | 0.79 |

| Age in years | 0.87 | 0.74–1.02 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.72–0.95 | 0.006 |

| Years smoked | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.25 |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.04 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.03 |

| First cigarette after waking up (after >60 minutes) | 0.68 | 0.25 | ||||

| Within 31 to 60 minutes | 1.33 | 0.62–2.86 | 1.18 | 0.70–1.99 | ||

| Within 6 to 30 minutes | 1.52 | 0.73–3.19 | 1.65 | 0.97–2.80 | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 1.23 | 0.48–3.10 | 1.40 | 0.68–2.88 | ||

| Intention to stop (no intention to stop) | 0.56 | 0.50 | ||||

| In the next 6 months | 0.45 | 0.10–2.02 | 0.71 | 0.13–3.94 | ||

| In the next 30 days | 0.53 | 0.15–1.89 | 0.52 | 0.11–2.45 | ||

| Currently not smoking | 0.24 | 0.03–1.83 | 0.32 | 0.05–1.91 | ||

| Last smoke stop attempt (no stop attempt) | 0.68 | 0.003 | ||||

| Less than 12 months ago | 1.30 | 0.68–2.51 | 2.69 | 1.53–4.73 | ||

| More than 12 months ago | 1.05 | 0.59–1.88 | 1.41 | 0.92–2.15 | ||

| Attended info. event before training (did not attend) | 0.55 | 0.31–0.97 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.44 | 0.75 |

| Compact and super compact training (standard training) | 0.50 | 0.25–1.01 | 0.05 | 1.52 | 0.91–2.56 | 0.11 |

| Training language German (French) | 0.56 | 0.30–1.05 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.49–1.36 | 0.44 |

| Comprehensibility of language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.70 | 0.52–0.94 | 0.02 | 1.04 | 0.80–1.36 | 0.75 |

| Satisfaction with trainer (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.60 | 1.07–2.38 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.56–1.08 | 0.14 |

| Satisfaction with training (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.68 | 0.49–0.95 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.82–1.43 | 0.56 |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped (none or only few helped) | 0.38 | 0.23–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.43–0.98 | 0.04 |

| Sleeping troubles (no sleeping troubles) | 0.42 | 0.22–0.79 | 0.007 | 0.74 | 0.49–1.12 | 0.15 |

| Increased appetite (no increased appetite) | 0.59 | 0.37–0.95 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.76–1.55 | 0.67 |

CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio The p-value is the overall p-value of the respective variable (Wald test). Restricted to participants with complete information in pre- and postintervention questionnaire (n = 840) and adjusted to pre- and postintervention questionnaire variables: participant gender, age, body mass index, work function, years smoked, cigarettes smoked per day, first cigarette smoked after waking up, intention to stop smoking, last smoke stop attempt, attendance to information event, attendance to all training sessions, cost account, time account, training type, training language, season by training begin, group size, trainer gender, trainer and participant gender, comprehensibility of trainer language, satisfaction with trainer, others, and training, withdrawal symptoms (sleeping troubles, increased appetite, increased anxiety, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, increased nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat, and other withdrawal symptoms), use of nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapy, number of helpful techniques learned.

Gender was not associated with nonabstinence at any time-point. Younger participants were less likely to abstain from smoking in the long run (OR 0.83, 95% CI 0.72–0.95).

Smoking-related aspects showed some influence on nonabstinence. Postintervention smoking relapse was related to the number of years smoked (OR 1.06, 95% CI 1.00–1.12) and the number of cigarettes smoked per day (OR 1.04, 95% CI 1.00–1.07). But only higher numbers of cigarettes smoked per day at baseline were still significantly associated with nonabstinence after 1 year (OR 1.03, 95% CI 1.00–1.06). Smoking a cigarette within 30 minutes after waking up showed a statistically nonsignificant association with postintervention and long-term nonabstinence. Failed long-term abstinence was particularly high in participants who had tried to stop smoking within the 12 months preceding the current intervention (OR 2.69, 95% CI 1.53–4.73).

With regard to training-related characteristics, only a poor evaluation of learned techniques translated into a high nonabstinence rate at 1-year follow-up (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.43–0.98). In contrast, most of the training characteristics analysed influenced nonabstinence in the short term, as evidenced by postintervention quit rate (not attending the information event before the training, poor comprehensibility of training language, low satisfaction with training, but not with trainer and considering learned techniques as not helpful, all increased the likelihood of short-term smoking relapse).

Self-reporting of sleeping troubles (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.22–0.79) and increased appetite (OR 0.59, 95% CI 0.37–0.95) was found to decrease rather than increase non-abstinence. But the presence of these or other symptoms are likely to be the result of smoking cessation and they did not predict nonabstinence in the long term.

No evidence was found for associations of nonabstinence with work function, complete attendance of training sessions, provision of cost or time for course by employer, season when training began, group size of training, trainer and participant gender difference, satisfaction with other participants, increased irritability or anxiety, difficulty to concentrate, depressed mood, increased nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat, and other withdrawal symptoms, BMI, as well as use of nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapy (see tables S1A and S1B).

Supplementary tables S2A and S2B (appendix 1) summarises the association of determinants with 1-year nonabstinence stratified by gender, age, use of nicotine replacement, and course type. Only the results for statistically significant interactions in the main effects models (determinants listed in table 4) are shown. Effect modifications by gender, age or training type were observed for the associations of 1-year nonabstinence with the variables satisfaction with trainer and increased appetite (all interaction p <0.05). Interestingly, increased appetite was associated with a higher likelihood of nonabstinence at the 1-year follow-up in women (OR 2.36, 95% CI 1.17–4.75), but not men. There was, furthermore, a suggestion that the statistically nonsignificant gender difference in quit rates may depend on the use of nicotine replacement.

To our knowledge, this is the first smoking cessation programme in a workplace setting that was implemented in the different languages and cultural contexts of a whole country. A rate of self-reported abstinence under real-life conditions of 18.6% with a full sample approach (ITT) at 12-month follow-up was achieved. The true success rate is probably underestimated, given a response rate of 49.9% and the conservative analysis approach in which all participants with missing data on abstinence were considered as nonabstinent. A higher abstinence rate could have been expected given the large percentage (86.1%) of highly motivated participants at the beginning of the training.

The 12-month abstinence rates after smoking cessation reported in the Cochrane reviews vary between 5 and 48% for behavioural group interventions in workplace and other settings [8, 10]. The study of Wenig et al. on an equivalent smoking cessation programme, but implemented in a routine care instead of a workplace setting in Germany, showed abstinence rates of 31.8% (ITT) at the 1-year follow-up. The difference in setting, the higher response rate at the 1-year follow-up (85.5% vs 49.9%) and a higher percentage of older participants (72.5% vs 47.5% older than 40 years), who are more likely to already exhibit smoking related symptoms, can in part explain the higher abstinence rate [5]. A 5-day plan for smoking cessation using similar group behavioural therapy in Switzerland with volunteers, who responded to an announcement in the local media, achieved an abstinence rate of 25% after 1 year [21]. A workplace intervention for healthcare employees in Switzerland, which was based on individual counselling and pharmacological support, reached 24-month quit rates of 37% (ITT). It consisted of intensive individual face-to-face counselling and a much higher endorsement of pharmacological support (93% vs 31% use of pharmacotherapy). Additionally, a re-intervention was offered after failed cessation or relapse. Nearly a quarter of the participants used this opportunity one or more times during the 24 months of the programme [19]. The relatively low response rate of 49.9% at 1-year follow-up in our study is possibly due to voluntary participation in the evaluation process of the programme and a high proportion of incomplete questionnaires (sufficient for evaluation but not for research and therefore excluded), the initial lower effort to obtain follow-up questionnaires due to financial restrictions and the collection of data in the context of a scientific evaluation rather than in a study planned from the start. The low response rate as a relevant factor could partly explain the lower quit rate at 1-year follow-up in the full sample approach (ITT).

The interventions described, including ours, differ in target population (e.g., socioeconomic status, professional background, age), context and type of intervention, as well as cost of the intervention. These differences need to be considered in assessing the cost-effectiveness of these different group interventions. Our data suggests that, for a subsample of workers, a low-cost intervention may be sufficient to achieve long-lasting quit rates. The optimal intervention seems to depend on the personal characteristics of the targeted smokers. Our data provide some guidance as to which worker subgroups benefit from more intensive and thus costly interventions. Concerning personal determinants of smoking cessation, the results of this modern smoking cessation programme suggest that younger and more addicted smokers and those with a recent attempt to quit need prolonged support in order to achieve long lasting abstinence. These results agree well with other studies that showed that the number of years smoked is inversely related to quitting [20–22]. Improved quit rates could be achieved, for example, through prolonged telephone counselling and the opportunity of a re-intervention for participants failing to stop smoking during the training or for those with a smoking relapse [19]. Whether participants with a long history of nicotine addiction also benefit from complementary individual face-to-face counselling or personalised pharmacological cessation support in addition to special attention during and after the training requires further studies in the context of workplace interventions; in this study, self-use of pharmacotherapy did not have an impact on quit rate. The suggestions for additional interventions acknowledge the fact that tobacco dependence is a chronic disease and often requires repeated intervention and multiple attempts to quit [37]. That older participants were shown to be more successful at sustaining abstinence is comparable with other studies [5, 19]. Older persons with health-related symptoms like breathlessness on exertion were shown to more likely than those with chronic sputum production to stay abstinent for 2 years [19].

The current study raises some concerns regarding the negative effect of compact course types on long-term abstinence. As compact course participants are overrepresented among responders this needs further study. The discrepancy between the associations of participants’ satisfaction with trainer or dissatisfaction with training with nonabstinence from smoking postintervention may be interpreted as discontent with the training format and content, while still acknowledging the trainers’ commitment to their abstinence attempt. In line with other studies, no associations were found between abstinence and work function, cost or time account, season in which training took place, group size, trainer gender, trainer and participant gender difference, or satisfaction with others [5, 19].

With respect to symptoms, a higher likelihood of abstinence at the end of the intervention was associated with sleeping problems and increased appetite. We assume that these symptoms are markers of successful smoking cessation rather than a motivational factor to quit. Also, weight gain was associated with abstinence at the postintervention assessment in the minimally adjusted models, but could not be analysed in the fully adjusted model owing to collinearity problems. Therefore, we cannot draw any conclusions concerning the influence of weight gain on abstinence. Neither these nor other symptoms (anxiety, irritability, poor concentration, depressed mood, nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat) were independently associated with 1-year abstinence, either due to the low prevalence of some of these withdrawal symptoms or because their assessment after the course did not identify persons needing additional support for long-term smoking cessation. This may not be true for increased appetite, which was associated with a lower 1-year abstinence rate in women only. The study of McKee et al. showed that women may perceive risks such as postcessation weight gain more strongly than men and are therefore less likely to be motivated to quit smoking and more likely to relapse to smoking [17].

The strengths of this study are that it covers three culturally diverse language regions, has a substantial sample size, a real-life setting, and a relatively high postintervention response rate. Furthermore, we distinguished between nonresponse and not reported abstinence in a multinomial regression analysis and thereby were able to evaluate the role of nonresponse in associations between quit rates and their determinants.

The limiting factors of this study include its observational character and lack of a control group, the limited number of workplace settings considered, the relative large number of variables studied in comparison to the number of participants, the small numbers of participants involved regarding some of the variables, the reliance on self-reported abstinence without confirmation by carbon monoxide measurements or cotinine testing, and its considerable nonresponse rate at the 1-year follow up. The carbon monoxide measurements were not undertaken because of limited financial resources. A limitation of carbon monoxide is furthermore its relative short half-life.

This type of study design and analyses in the absence of a randomised intervention with a control group can provide only suggestive, but not conclusive, evidence on associations between determinants and smoking cessation. Finally, these results may not be applicable to other populations and workplace settings.

In conclusion, this relatively low-cost intervention showed that a reasonable percentage of smokers can be motivated to achieve long-lasting smoking cessation in the context of group behavioural therapy programmes offered in workplace settings. However, young and heavy smokers potentially benefit from re-intervention and additional individual counselling. The problem of increased appetite and subsequent weight gain after smoking cessation may need specific attention in women.

Future studies are still needed to optimise a cost-effective group-level yet personalised counselling approach. Additional factors deserve to be studied, such as the impact of social support (spouse, family, friends, co-workers), workplace environment (regulations, financial support/incentive), trainer characteristics (experience, profession), and other health issues (comorbidity, multiple drug use, mental illnesses).

Table S1 A: Independent determinants of nonabstinence in minimally adjusted models

| Determinants (reference group) | Minimally adjusted models* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Postintervention | 1-year follow-up | |||||

| Multilevel logistic model | Multilevel logistic model | |||||

| Nonabstinence vs abstinence | Nonabstinence vs abstinence | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Participant gender male (female) | 0.65 | 0.42–0.99 | 0.04 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.37 | 0.86 |

| Age in years | 0.96 | 0.95–0.99 | 0.001 | 0.98 | 0.97–1.00 | 0.02 |

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 | 0.30 | 0.97 | 0.94–1.01 | 0.21 |

| Only management or with employee together (only employee) | 0.61 | 0.36–1.03 | 0.06 | 0.81 | 0.55–1.17 | 0.26 |

| Work function unknown (only employee) | 0.75 | 0.43–1.30 | 0.30 | 0.80 | 0.52–1.22 | 0.29 |

| Years smoked | 1.07 | 1.02–1.13 | 0.01 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.18 |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.04 | 1.02–1.07 | 0.002 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.06 | 0.001 |

| First cigarette after waking up within 31 to 60 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 1.49 | 0.74–3.00 | 0.27 | 1.35 | 0.84–2.16 | 0.21 |

| First cigarette after waking up within 6 to 30 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 2.11 | 1.12–3.99 | 0.02 | 2.12 | 1.36–3.30 | 0.001 |

| First cigarette after waking up within 5 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 2.58 | 1.22–5.44 | 0.01 | 2.17 | 1.23–3.86 | 0.01 |

| Intention to stop in the next 6 months (no intention to stop) | 0.48 | 0.12–1.90 | 0.30 | 0.60 | 0.11–3.11 | 0.54 |

| Intention to stop in the next 30 days (no intention to stop) | 0.45 | 0.14–1.45 | 0.18 | 0.49 | 0.11–2.20 | 0.36 |

| Intention: currently not smoking§ (no intention to stop) | 0.20 | 0.03–1.34 | 0.10 | 0.30 | 0.05–1.65 | 0.17 |

| Last smoke stop attempt less than 12 months ago (no stop attempt) | 1.16 | 0.65–2.10 | 0.61 | 2.42 | 1.42–4.11 | 0.001 |

| Last smoke stop attempt more than 12 months ago (no stop attempt) | 0.99 | 0.59–1.66 | 0.96 | 1.33 | 0.90–1.98 | 0.15 |

| Attended information event before training (did not attend) | 0.86 | 0.55–1.35 | 0.51 | 0.97 | 0.69–1.36 | 0.85 |

| Attended all training sessions (did not attend all) | 1.33 | 0.78–2.25 | 0.29 | 0.74 | 0.48–1.14 | 0.17 |

| Training costs born by participant (by company) | 1.61 | 0.83–3.15 | 0.16 | 0.95 | 0.55–1.64 | 0.85 |

| Training time born by participant (by company) | 0.71 | 0.41–1.21 | 0.20 | 1.07 | 0.70–1.65 | 0.74 |

| Compact and super compact training (standard training) | 0.77 | 0.46–1.29 | 0.32 | 1.23 | 0.84–1.79 | 0.29 |

| Training language German (French) | 0.37 | 0.24–0.58 | <0.001 | 1.04 | 0.73–1.48 | 0.82 |

| Season winter (summer) | 1.10 | 0.71–1.71 | 0.67 | 1.44 | 1.02–2.02 | 0.04 |

| Group size | 0.99 | 0.92–1.07 | 0.84 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 | 0.38 |

| Trainer gender male (female) | 0.87 | 0.54–1.39 | 0.56 | 0.69 | 0.49–0.96 | 0.03 |

| Trainer and participant same gender (different gender) | 0.84 | 0.54–1.32 | 0.46 | 0.82 | 0.58–1.16 | 0.25 |

| Comprehensibility of training language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.80 | 0.62–1.04 | 0.10 | 0.96 | 0.74–1.24 | 0.74 |

| Satisfaction with trainer (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.07 | 0.80–1.43 | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.60–0.98 | 0.03 |

| Satisfaction with others (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.04 | 0.79–1.37 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.73–1.14 | 0.40 |

| Satisfaction with oneself (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.48 | 0.39–0.60 | <0.001 | 0.57 | 0.46–0.72 | <0.001 |

| Satisfaction with training (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.76 | 0.60–0.96 | 0.02 | 0.88 | 0.72–1.09 | 0.24 |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped me (none or only few helped) | 0.42 | 0.28–0.64 | <0.001 | 0.69 | 0.48–0.99 | 0.05 |

| Recommended training at postintervention | 0.67 | 0.26–1.71 | 0.40 | 0.41 | 0.12–1.37 | 0.15 |

| Recommended training at 1-year follow-up | 0.39 | 0.17–0.90 | 0.03 | 0.19 | 0.07–0.55 | 0.002 |

| Sleeping troubles (no sleeping troubles) | 0.49 | 0.27–0.87 | 0.02 | 0.95 | 0.65–1.38 | 0.79 |

| Increased appetite (no increased appetite) | 0.54 | 0.35–0.83 | 0.01 | 1.05 | 0.76–1.46 | 0.75 |

| Increased anxiety (no increased anxiety) | 1.86 | 0.95–3.62 | 0.07 | 2.38 | 1.05–5.38 | 0.04 |

| Increased irritability (no increased irritability) | 0.89 | 0.58–1.37 | 0.61 | 0.98 | 0.70–1.36 | 0.89 |

| Difficulty concentrating (no difficulty concentrating) | 1.56 | 0.92–2.64 | 0.10 | 1.92 | 1.14–3.22 | 0.01 |

| Depressed mood (no depressed mood) | 1.61 | 0.99–2.63 | 0.05 | 1.41 | 0.88–2.26 | 0.16 |

| Increased nervousness or agitation (no increased nervousness or agitation) | 1.39 | 0.92–2.12 | 0.12 | 1.39 | 0.98–1.97 | 0.07 |

| Slower heartbeat (no slower heartbeat) | 0.68 | 0.20–2.34 | 0.54 | 1.56 | 0.64–3.84 | 0.33 |

| Other withdrawal symptoms (no other withdrawal symptoms) | 1.08 | 0.58–2.00 | 0.82 | 1.33 | 0.78–2.26 | 0.29 |

| Weight gain at postintervention | 0.30 | 0.18–0.52 | <0.001 | 0.80 | 0.57–1.12 | 0.19 |

| Weight gain at 1-year follow-up | 0.16 | 0.08–0.31 | <0.001 | 0.08 | 0.05–0.13 | <0.001 |

| NRT only (no pharmacotherapy) | 1.42 | 0.90–2.25 | 0.13 | 1.19 | 0.81–1.73 | 0.38 |

| Supportive medications only (no pharmacotherapy) |

0.87 | 0.24–3.10 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 0.42–2.79 | 0.86 |

| NRT and supportive medications (no pharmacotherapy) |

3.58 | 0.86–14.97 | 0.08 | 1.34 | 0.28–6.49 | 0.72 |

BMI = body mass index; CI = confidence interval; NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; OR = odds ratio The p-value is the overall p-value of the respective variable (Wald test). * Restricted to participants with complete information in pre- and postintervention questionnaires (n = 840). The association of the outcomes with each of the determinants was adjusted for participant gender, age, training language, and work function. § 30 participants that probably stopped smoking before beginning the training and succeeded in staying abstinent until then.

Table S1B Independent determinants of nonabstinence in fully adjusted models.

| Determinants (reference group) | Fully adjusted models* | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-training | 1-year follow-up | ||||||||||||

| Multilevel logistic model | Multilevel logistic model | Multinomial model | |||||||||||

| Nonabstinence vs abstinence | Nonabstinence vs abstinence | Nonabstinence vs abstinence | Nonabstinence vs abstinence | ||||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Participant gender male (female) | 0.68 | 0.40–1.14 | 0.14 | 0.95 | 0.63–1.43 | 0.80 | 0.86 | 0.52–1.42 | 0.56 | 1.07 | 0.62–1.84 | 0.80 | |

| Age in years | 0.87 | 0.74–1.02 | 0.08 | 0.83 | 0.72–0.95 | 0.01 | 0.85 | 0.74–0.97 | 0.02 | 0.82 | 0.71–0.94 | 0.01 | |

| BMI | 0.97 | 0.91–1.03 | 0.29 | 0.97 | 0.93–1.02 | 0.24 | 0.98 | 0.93–1.03 | 0.36 | 0.97 | 0.92–1.02 | 0.25 | |

| Only management or with employee together (only employee) | 0.61 | 0.35–1.06 | 0.08 | 0.81 | 0.53–1.24 | 0.34 | 0.99 | 0.60–1.63 | 0.97 | 0.65 | 0.40–1.06 | 0.08 | |

| Work function unknown (only employee) | 0.73 | 0.40–1.33 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.45–1.13 | 0.15 | 0.76 | 0.47–1.23 | 0.27 | 0.69 | 0.40–1.22 | 0.20 | |

| Years smoked | 1.06 | 1.00–1.12 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.05 | 0.25 | 1.02 | 0.99–1.06 | 0.22 | 1.01 | 0.98–1.05 | 0.52 | |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.04 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.06 | 0.03 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.09 | 1.03 | 1.00–1.07 | 0.06 | |

| First cigarette after waking up within 31 to 60 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 1.33 | 0.62–2.86 | 0.46 | 1.18 | 0.70–1.99 | 0.54 | 1.28 | 0.69–2.38 | 0.44 | 1.09 | 0.61–1.96 | 0.77 | |

| First cigarette after waking up within 6 to 30 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 1.52 | 0.73–3.19 | 0.26 | 1.65 | 0.97–2.80 | 0.06 | 1.20 | 0.65–2.20 | 0.56 | 2.30 | 1.28–4.12 | 0.01 | |

| First cigarette after waking up within 5 minutes (after >60 minutes) | 1.23 | 0.48–3.10 | 0.67 | 1.40 | 0.68–2.88 | 0.36 | 1.11 | 0.50–2.45 | 0.80 | 1.82 | 0.77–4.30 | 0.17 | |

| Intention to stop in the next 6 months (no intention to stop) | 0.45 | 0.10–2.02 | 0.30 | 0.71 | 0.13–3.94 | 0.69 | 0.55 | 0.08–3.61 | 0.53 | 1.02 | 0.17–6.20 | 0.98 | |

| Intention to stop in the next 30 days (no intention to stop) | 0.53 | 0.15–1.89 | 0.33 | 0.52 | 0.11–2.45 | 0.41 | 0.43 | 0.08–2.31 | 0.33 | 0.67 | 0.13–3.52 | 0.64 | |

| Intention: currently not smoking§ (no intention to stop) | 0.24 | 0.03–1.83 | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.05–1.91 | 0.21 | 0.12 | 0.02–0.84 | 0.03 | 0.68 | 0.12–3.84 | 0.66 | |

| Last smoke stop attempt less than 12 months ago (no stop attempt) | 1.30 | 0.68–2.51 | 0.43 | 2.69 | 1.53–4.73 | 0.001 | 2.38 | 1.33–4.26 | 0.004 | 3.12 | 1.69–5.78 | <0.001 | |

| Last smoke stop attempt more than 12 months ago (no stop attempt) | 1.05 | 0.59–1.88 | 0.87 | 1.41 | 0.92–2.15 | 0.11 | 1.26 | 0.82–1.93 | 0.30 | 1.62 | 1.06–2.48 | 0.03 | |

| Attended information event before training (did not attend) | 0.55 | 0.31–0.97 | 0.04 | 0.93 | 0.60–1.44 | 0.75 | 0.92 | 0.59–1.46 | 0.74 | 0.95 | 0.56–1.61 | 0.86 | |

| Attended all training sessions (did not attend all) | 1.80 | 0.99–3.29 | 0.05 | 0.79 | 0.49–1.29 | 0.35 | 0.82 | 0.45–1.47 | 0.50 | 0.76 | 0.45–1.28 | 0.30 | |

| Training costs born by participant (by company) | 1.66 | 0.76–3.63 | 0.21 | 1.17 | 0.62–2.22 | 0.62 | 1.01 | 0.49–2.10 | 0.97 | 1.34 | 0.68–2.64 | 0.40 | |

| Training time born by participant (by company) | 0.65 | 0.35–1.21 | 0.18 | 0.91 | 0.56–1.48 | 0.71 | 0.90 | 0.50–1.61 | 0.72 | 0.93 | 0.53–1.63 | 0.81 | |

| Compact and super compact training (standard training) | 0.50 | 0.25–1.01 | 0.05 | 1.52 | 0.91–2.56 | 0.11 | 1.96 | 1.16–3.31 | 0.01 | 1.28 | 0.70–2.34 | 0.42 | |

| Training language German (French) | 0.56 | 0.30–1.05 | 0.07 | 0.82 | 0.49–1.36 | 0.44 | 0.48 | 0.28–0.83 | 0.01 | 1.47 | 0.81–2.68 | 0.21 | |

| Season winter (summer) | 1.35 | 0.81–2.25 | 0.25 | 1.33 | 0.91–1.96 | 0.14 | 1.39 | 0.90–2.15 | 0.13 | 1.25 | 0.81–1.94 | 0.31 | |

| Group size | 1.01 | 0.92–1.11 | 0.79 | 0.96 | 0.89–1.03 | 0.27 | 0.97 | 0.90–1.05 | 0.42 | 0.95 | 0.86–1.04 | 0.25 | |

| Trainer gender male (female) | 0.74 | 0.43–1.28 | 0.28 | 0.77 | 0.52–1.15 | 0.21 | 0.77 | 0.49–1.20 | 0.25 | 0.79 | 0.47–1.35 | 0.39 | |

| Trainer and participant same gender (different gender) | 0.81 | 0.49–1.32 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 0.54–1.17 | 0.25 | 0.76 | 0.48–1.19 | 0.23 | 0.86 | 0.53–1.39 | 0.53 | |

| Comprehensibility of training language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.70 | 0.52–0.94 | 0.02 | 1.04 | 0.80–1.36 | 0.75 | 1.13 | 0.81–1.58 | 0.47 | 0.98 | 0.76–1.27 | 0.88 | |

| Satisfaction with trainer (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.60 | 1.07–2.38 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.56–1.08 | 0.14 | 0.76 | 0.53–1.08 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.56–1.16 | 0.25 | |

| Satisfaction with others (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.60 | 0.79–1.53 | 0.02 | 0.78 | 0.76–1.29 | 0.14 | 0.76 | 0.78–1.34 | 0.13 | 0.81 | 0.73–1.24 | 0.25 | |

| Satisfaction with oneself (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Satisfaction with training (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.68 | 0.49–0.95 | 0.03 | 1.09 | 0.82–1.43 | 0.56 | 1.15 | 0.83–1.58 | 0.41 | 1.03 | 0.77–1.38 | 0.85 | |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped me (none or only few helped) | 0.38 | 0.23–0.61 | <0.001 | 0.65 | 0.43–0.98 | 0.04 | 0.69 | 0.43–1.09 | 0.11 | 0.61 | 0.40–0.91 | 0.02 | |

| Recommended training at postintervention | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Recommended training at 1-year follow-up | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Sleeping troubles (no sleeping troubles) | 0.42 | 0.22–0.79 | 0.01 | 0.74 | 0.49–1.12 | 0.15 | 0.75 | 0.47–1.20 | 0.23 | 0.73 | 0.47–1.12 | 0.15 | |

| Increased appetite (no increased appetite) | 0.59 | 0.37–0.95 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 0.76–1.55 | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.67–1.59 | 0.90 | 1.14 | 0.73–1.78 | 0.57 | |

| Increased anxiety (no increased anxiety) | 1.61 | 0.73–3.56 | 0.24 | 1.73 | 0.71–4.20 | 0.23 | 1.26 | 0.44–3.65 | 0.67 | 2.32 | 0.83–6.45 | 0.11 | |

| Increased irritability (no increased irritability) | 0.74 | 0.42–1.28 | 0.28 | 0.78 | 0.53–1.16 | 0.23 | 0.87 | 0.54–1.41 | 0.58 | 0.71 | 0.45–1.12 | 0.14 | |

| Difficulty concentrating (no difficulty concentrating) | 1.54 | 0.85–2.79 | 0.15 | 1.65 | 0.94–2.90 | 0.08 | 1.70 | 0.87–3.34 | 0.12 | 1.60 | 0.87–2.97 | 0.13 | |

| Depressed mood (no depressed mood) | 1.69 | 0.93–3.08 | 0.09 | 0.93 | 0.54–1.60 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.57–1.74 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.48–1.58 | 0.64 | |

| Increased nervousness or agitation (no increased nervousness or agitation) | 1.49 | 0.89–2.51 | 0.13 | 1.23 | 0.82–1.84 | 0.33 | 1.19 | 0.72–1.96 | 0.49 | 1.25 | 0.76–2.06 | 0.38 | |

| Slower heartbeat (no slower heartbeat) | 1.08 | 0.27–4.24 | 0.92 | 1.63 | 0.61–4.34 | 0.33 | 1.96 | 0.65–5.90 | 0.23 | 1.38 | 0.44–4.27 | 0.58 | |

| Other withdrawal symptoms (no other withdrawal symptoms) | 0.86 | 0.43–1.73 | 0.67 | 1.27 | 0.72–2.24 | 0.41 | 1.24 | 0.68–2.27 | 0.48 | 1.30 | 0.72–2.32 | 0.38 | |

| Weight gain at postintervention | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Weight gain at 1-year follow-up | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

| NRT only (no pharmacotherapy) | 1.21 | 0.73–2.03 | 0.46 | 1.03 | 0.68–1.57 | 0.88 | 1.19 | 0.72–1.97 | 0.51 | 0.87 | 0.56–1.35 | 0.53 | |

| Supportive medications only (no pharmacotherapy) |

0.50 | 0.12–1.97 | 0.32 | 0.72 | 0.26–2.02 | 0.54 | 0.99 | 0.29–3.41 | 0.99 | 0.51 | 0.16–1.66 | 0.26 | |

| NRT and supportive medications (no pharmacotherapy) |

2.20 | 0.51–9.53 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 0.14–3.84 | 0.70 | 1.03 | 0.20–5.38 | 0.97 | 0.50 | 0.08–3.01 | 0.45 | |

The p-value is the overall p-value of the respective variable (Wald test). * Restricted to participants with complete information in pre- and postintervention questionnaires (n = 840) and adjusted to pre- and postintervention questionnaire variables: participant gender, age, body mass index, work function, years smoked, cigarettes smoked per day, first cigarette smoked after waking up, intention to stop smoking, last smoke stop attempt, attendance to information event, attendance to all training sessions, cost account, time account, training type, training language, season by training begin, group size, trainer gender, trainer and participant gender, comprehensibility of trainer language, satisfaction with trainer, others and training, withdrawal symptoms (sleeping troubles, increased appetite, increased anxiety, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, increased nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat, and other withdrawal symptoms), use of nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapy, number of helpful techniques learned. § 30 participants that probably stopped smoking before beginning the training and succeeded in staying abstinent until then.

| Table S2A: Stratified independent determinants of nonabstinence at 1-year follow-up: gender and age. | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinants (reference group) | Male participant | Female participant | Inter-action | ≤40 years old | >40 years old | Inter-action | ||||

| OR | p-value | OR | p-value | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | p-value | |

| Participant gender male (female) | – | – | – | – | – | 0.85 | 0.60 | 1.19 | 0.58 | 0.48 |

| Age in years | 0.81 | 0.03 | 0.79 | 0.05 | 0.99 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Years smoked | 1.02 | 0.34 | 1.02 | 0.55 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.67 | 1.01 | 0.33 | 0.42 |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.03 | 0.10 | 1.04 | 0.24 | 0.89 | 1.05 | 0.10 | 1.03 | 0.16 | 0.65 |

| First cigarette after waking up (after >60 minutes) | 0.20 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| Within 31 to 60 minutes | 0.87 | 0.72 | 1.82 | 0.22 | 1.93 | 0.11 | 0.65 | 0.31 | ||

| Within 6 to 30 minutes | 1.38 | 0.40 | 2.40 | 0.06 | 1.46 | 0.34 | 1.92 | 0.13 | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 0.75 | 0.58 | 4.28 | 0.03 | 1.44 | 0.52 | 1.34 | 0.61 | ||

| Intention to stop (no intention)* | 0.81 | 0.43 | ||||||||

| In the next 6 months | 2.50 | 0.37 | – | 0.97 | 0.75 | 0.82 | 0.24 | 0.31 | ||

| In the next 30 days | 1.53 | 0.63 | – | 0.97 | 0.38 | 0.40 | 0.43 | 0.48 | ||

| Last smoke stop attempt (no attempt) | 0.64 | 0.44 | ||||||||

| Less than 12 months ago | 3.99 | 0.001 | 2.13 | 0.14 | 4.57 | 0.001 | 2.32 | 0.06 | ||

| More than 12 months ago | 1.50 | 0.16 | 1.17 | 0.68 | 1.46 | 0.22 | 1.49 | 0.25 | ||

| Attended info event before training (did not attend) | 0.82 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 0.91 | 0.79 | 1.55 | 0.20 | 0.55 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| Compact and super compact training (standard training) | 1.43 | 0.29 | 1.23 | 0.69 | 0.81 | 1.63 | 0.23 | 1.32 | 0.50 | 0.73 |

| Training language German (French) | 0.95 | 0.90 | 0.94 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 0.67 |

| Comprehensibility of language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.84 | 0.35 | 1.57 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 0.86 | 0.58 | 1.18 | 0.37 | 0.30 |

| Satisfaction with trainer (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.68 | 0.09 | 0.81 | 0.50 | 0.65 | 1.15 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| Satisfaction with training (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.25 | 0.23 | 0.93 | 0.78 | 0.36 | 0.87 | 0.50 | 1.37 | 0.15 | 0.12 |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped (none or only few helped) | 0.70 | 0.22 | 0.59 | 0.17 | 0.71 | 0.67 | 0.23 | 0.62 | 0.12 | 0.82 |

| Sleeping troubles (no sleeping troubles) | 0.59 | 0.05 | 0.96 | 0.93 | 0.31 | 0.69 | 0.27 | 0.65 | 0.15 | 0.89 |

| Increased appetite (no increased appetite) | 0.85 | 0.51 | 2.36 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.43 | 0.22 | 0.94 | 0.83 | 0.31 |

OR = odds ratio p-values from the Wald test Restricted to participants with complete information in pre- and postintervention questionnaires (n = 840*) and adjusted to pre- and postintervention questionnaire variables: participant gender, age, body mass index, work function, years smoked, cigarettes smoked per day, first cigarette smoked after waking up, intention to stop smoking, last smoke stop attempt, attendance to information event, attendance to all training sessions, cost account, time account, training type, training language, season by training begin, group size, trainer gender, trainer and participant gender, comprehensibility of trainer language, satisfaction with trainer, others and training, withdrawal symptoms (sleeping troubles, increased appetite, increased anxiety, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, increased nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat, and other withdrawal symptoms), use of nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapy, number of helpful techniques learned. * 25 additional participants excluded from this analysis because category 4 “currently not smoking” of the variable “intention to stop smoking” could not be estimated in subgroup analysis (n = 815).

Table S2B Stratified independent determinants of nonabstinence at 1-year follow-up: pharmacotherapy use and type of training.

| No pharmaco-therapy | Pharmaco-therapy | Inter-action | Standard | Compact | Inter-action | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Determinants (reference group) | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | p-value | OR | p-value | OR | p-value | p-value |

| Participant gender male (female) | 1.18 | 0.54 | 0.61 | 0.26 | 0.04 | 0.83 | 0.53 | 1.19 | 0.60 | 0.96 |

| Age in years | 0.80 | 0.01 | 0.83 | 0.21 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.07 | 0.86 | 0.18 | 0.39 |

| Years smoked | 1.02 | 0.26 | 1.00 | 0.89 | 0.49 | 1.03 | 0.22 | 1.01 | 0.55 | 0.70 |

| Cigarettes per day | 1.04 | 0.03 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.37 | 1.06 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.84 | 0.08 |

| First cigarette after waking up (after >60 minutes) | 0.16 | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Within 31 to 60 minutes | 1.33 | 0.36 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 1.05 | 0.91 | 1.68 | 0.21 | ||

| Within 6 to 30 minutes | 1.65 | 0.13 | 1.36 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 3.13 | 0.01 | ||

| Within 5 minutes | 2.78 | 0.06 | 0.53 | 0.42 | 0.73 | 0.58 | 2.66 | 0.08 | ||

| Intention to stop (no intention)* | 0.36 | 0.64 | ||||||||

| In the next 6 months | 0.59 | 0.58 | – | 0.99 | 1.33 | 0.79 | – | 0.97 | ||

| In the next 30 days | 0.61 | 0.56 | – | 0.99 | 0.78 | 0.78 | – | 0.97 | ||

| Last smoke stop attempt (no attempt) | 0.23 | 0.96 | ||||||||

| Less than 12 months ago | 2.14 | 0.03 | 7.13 | 0.01 | 3.17 | 0.01 | 2.79 | 0.03 | ||

| More than 12 months ago | 1.25 | 0.42 | 1.47 | 0.38 | 1.33 | 0.38 | 1.38 | 0.32 | ||

| Attended info event before training (did not attend) | 1.10 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.92 | 0.80 | 0.85 | 0.64 | 0.95 |

| Compact and super compact training (standard training) | 1.64 | 0.13 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.45 | – | – | – | – | – |

| Training language German (French) | 0.87 | 0.68 | 0.51 | 0.25 | 0.48 | 1.06 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 0.64 |

| Comprehensibility of language (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.30 | 0.15 | 0.83 | 0.47 | 0.14 | 1.45 | 0.09 | 0.77 | 0.30 | 0.05 |

| Satisfaction with trainer (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 0.64 | 0.03 | 1.13 | 0.75 | 0.24 | 0.80 | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.25 | 0.84 |

| Satisfaction with training (1 = very low to 6 = very high) | 1.11 | 0.54 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.96 | 1.08 | 0.76 | 1.07 | 0.72 | 0.98 |

| Many or nearly all learned techniques helped (none or only few helped) | 0.69 | 0.14 | 0.48 | 0.12 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.69 | 0.22 | 0.99 |

| Sleeping troubles (no sleeping troubles) | 0.56 | 0.03 | 1.04 | 0.93 | 0.29 | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.68 | 0.21 | 0.96 |

| Increased appetite (no increased appetite) | 1.34 | 0.21 | 0.80 | 0.58 | 0.23 | 1.78 | 0.04 | 0.73 | 0.25 | 0.02 |

OR = odds ratio p-values from the Wald test Restricted to participants with complete information in pre- and postintervention questionnaires (n = 840*) and adjusted to pre- and postintervention questionnaire variables: participant gender, age, body mass index, work function, years smoked, cigarettes smoked per day, first cigarette smoked after waking up, intention to stop smoking, last smoke stop attempt, attendance to information event, attendance to all training sessions, cost account, time account, training type, training language, season by training begin, group size, trainer gender, trainer and participant gender, comprehensibility of trainer language, satisfaction with trainer, others and training, withdrawal symptoms (sleeping troubles, increased appetite, increased anxiety, increased irritability, difficulty concentrating, depressed mood, increased nervousness or agitation, slower heartbeat, and other withdrawal symptoms), use of nicotine replacement or other pharmacological therapy, number of helpful techniques learned. * 25 additional participants excluded from this analysis because category 4 “currently not smoking” of the variable “intention to stop smoking” could not be estimated in subgroup analysis (n = 815).

“Enterprise Smoke-free” team (www.unternehmenrauchfrei.ch): Margit Heintz, Anja Reimann, Pia Bitzi, Marlis Waser, Iris Walter, Grégoire Vittoz, Stéphanie Zwissig Vuissoz, Yvonne Uebelhart, Virginie Bréhier, and Claudio Paulin.

Trainers: Anne-Lise Aubry, Renate Bernhardsgrütter, Pia Bitzi, Michael Boguslaw, Judi Bonetti, Virginie Bréhier, Els Bühler, Lydia Eisenmann, Marlise Fehlmann, Regula Friedl, Catherine Gex, Richard Gibel, Christophe Gut, Elena Haechler-Papais, Lilo Halter, Andrea Heeb, Sandra Isler, Bettina Janko-Schirmer, Anne-Christine Joris Brouwer, Claudine Joris Mayoraz, Sandra Lauterer, Katrin Lerch, Silvia Loosli, Josiane Ludi, Claudia Marin-Galli, Markus Marthaler, Paula Martin, Michèle M. Salmony Di Stefano, Elke Schelling, Claudia Thon-Mahrt, Grégoire Vittoz, Eleonora Volken-Heilmann, Iris Walter, Marlis Waser, Barbara Wehrli, Carmen Wicki, Peter Woodtli, Monika Zimmermann.

Lungenliga beider Basel (www.llbb.ch)

IFT Institut für Therapieforschung, München (www.ift.de)

IFT-Gesundheitsförderung, München (www.ift-gesundheitsfoerderung.de)

This work was supported by the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute Basel (Switzerland) and by the Lung Association Basel (Switzerland). No conflicts of interest are to be declared.

1Gmel G, Kuendig H, Notari L, Gmel C, Flury R. Suchtmonitoring Schweiz - Konsum von Tabak in der Schweiz im Jahr 2012. Addiction Monitoring in Switzerland. 2013.

2Junker C. Smoking-attributable mortality in Switzerland. Estimation for the years 1995 to 2007. Federal Statistical Office. 2009.

3Wieser S, Kauer L, Schmidhauser S, et al. Synthesis report – Economic evaluation of prevention measures in Switzerland. Federal Office of Public Health. 2009.

4 Wu J , Sin DD . Improved patient outcome with smoking cessation: when is it too late? Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2011;6:259–67.

5 Wenig JR , Erfurt L , Kröger CB , Nowak D . Smoking cessation in groups--who benefits in the long term? Health Educ Res. 2013;28(5):869–78. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt086

6 Song F , Huttunen-Lenz M , Holland R . Effectiveness of complex psycho-educational interventions for smoking relapse prevention: an exploratory meta-analysis. J Public Health (Oxf). 2010;32(3):350–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdp109

7 Cromwell J , Bartosch WJ , Fiore MC , Hasselblad V , Baker T ; Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Cost-effectiveness of the clinical practice recommendations in the AHCPR guideline for smoking cessation. JAMA. 1997;278(21):1759–66. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1997.03550210057039

8 Stead LF , Lancaster T . Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;(2):CD001007.

9 Hajek P . Current issues in behavioral and pharmacological approaches to smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 1996;21(6):699–707. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(96)00029-9

10 Cahill K , Lancaster T . Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2(2):CD003440.

11WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. World Health Organization. 2003. http://www.who.int/tobacco/framework/WHO_FCTC_english.pdf.

12Nichtrauchen kann man lernen. Unternehmen rauchfrei, Lungen Liga. 2012. http://www.unternehmenrauchfrei.ch/fileadmin/user_upload/PDF/Nichtrauchen_kann_man_lernen.pdf.

13 Gradl S , Kroeger CB , Floeter S , Piontek D . Effectiveness of a modern smoking cessation programme based on international guidelines. Verhaltensther Verhaltensmed. 2009;30(2):169–85.

14 Durham AD , Diethelm P , Cornuz J . Why did Swiss citizens refuse a comprehensive second-hand smoke ban? Swiss Med Wkly. 2014;144:w13983.

15 Osler M , Prescott E . Psychosocial, behavioural, and health determinants of successful smoking cessation: a longitudinal study of Danish adults. Tob Control. 1998;7(3):262–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.7.3.262

16 Monsó E , Campbell J , Tønnesen P , Gustavsson G , Morera J . Sociodemographic predictors of success in smoking intervention. Tob Control. 2001;10(2):165–9. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/tc.10.2.165

17 McKee SA , O’Malley SS , Salovey P , Krishnan-Sarin S , Mazure CM . Perceived risks and benefits of smoking cessation: gender-specific predictors of motivation and treatment outcome. Addict Behav. 2005;30(3):423–35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.05.027

18 Borrelli B , Hogan JW , Bock B , Pinto B , Roberts M , Marcus B . Predictors of quitting and dropout among women in a clinic-based smoking cessation program. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16(1):22–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.16.1.22

19 Stolz D , Scherr A , Seiffert B , Kuster M , Meyer A , Fagerström KO , et al. Predictors of success for smoking cessation at the workplace: a longitudinal study. Respiration. 2014;87(1):18–25. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1159/000346646

20 Matheny KB , Weatherman KE . Predictors of smoking cessation and maintenance. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54(2):223–35. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199802)54:2<223::AID-JCLP12>3.0.CO;2-L

21 Frikart M , Etienne S , Cornuz J , Zellweger J-P . Five-day plan for smoking cessation using group behaviour therapy. Swiss Med Wkly. 2003;133(3-4):39–43. Available from: https://smw.ch/en/article/doi/smw.2003.10068/

22 Meamar R , Etedali F , Sereshti N , Sabour E , Samani MD , Ardakani MR , et al. Predictors of smoking cessation and duration: implication for smoking prevention. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(Suppl 2):S194–200.

23 Boardman T , Catley D , Mayo MS , Ahluwalia JS . Self-efficacy and motivation to quit during participation in a smoking cessation program. Int J Behav Med. 2005;12(4):266–72. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm1204_7

24 Garvey AJ , Bliss RE , Hitchcock JL , Heinold JW , Rosner B . Predictors of smoking relapse among self-quitters: a report from the Normative Aging Study. Addict Behav. 1992;17(4):367–77. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(92)90042-T

25 Fisher EB, Jr , Bishop DB , Levitt-Gilmour T , Cappello MT , Ashenberg ZS , Newman E . Social support in worksite smoking cessation: qualitative analysis of the EASE project. Am J Health Promot. 1994;9(1):39–47, 75. doi:.https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-9.1.39

26 Cahill K , Perera R . Competitions and incentives for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(4):CD004307.

27 Alterman AI , Gariti P , Mulvaney F . Short- and long-term smoking cessation for three levels of intensity of behavioral treatment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(3):261–4. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.15.3.261

28 Hendricks PS , Delucchi KL , Benowitz NL , Hall SM . Clinical significance of early smoking withdrawal effects and their relationships with nicotine metabolism: preliminary results from a pilot study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014;16(5):615–20. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntt204

29 Froom P , Melamed S , Benbassat J . Smoking cessation and weight gain. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(6):460–4.

30 Cahill K , Stevens S , Perera R , Lancaster T . Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation: an overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;5(5):CD009329.

31Abrams DB. The Tobacco Dependence Treatment Handbook: A Guide to Best Practices. New York: Guilford Press; 2003.

32Linehan M. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993.

33Hayes SC. Get Out of Your Mind & Into Your Life: The New Acceptance & Commitment Therapy. Oakland: New Harbinger Publications; 2005.

34 West R , Hajek P , Stead L , Stapleton J . Outcome criteria in smoking cessation trials: proposal for a common standard. Addiction. 2005;100(3):299–303. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00995.x

35 Fagerstrom KO , Schneider NG . Measuring nicotine dependence: a review of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. J Behav Med. 1989;12(2):159–82. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00846549

36 Hughes JR , Hatsukami D . Signs and symptoms of tobacco withdrawal. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1986;43(3):289–94. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800030107013

37 Fiore MC , Jaen CR , Baker TB , et al., Clinical Practice Guideline Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence 2008 Update Panel, Liaisons, and Staff. A clinical practice guideline for treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update. A U.S. Public Health Service report. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35(2):158–76. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.009

YH, CQ, and NPH developed the conceptual framework for and conducted the research.

LG, CQ, and YH extracted and checked the data.

LG and CS gave statistical support.

YH, CQ, and NPH wrote the publication, with additional input from all authors.

This work was supported by the Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute Basel (Switzerland) and by the Lung Association Basel (Switzerland). No conflicts of interest are to be declared.