Sources of distress for physicians and nurses working in Swiss neonatal intensive care units

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14477

Sabine D.

Kleina, Hans Ulrich

Buchera, Manya J.

Hendriksab, Ruth

Baumann-Hölzlec, Jürg C.

Streulib, Thomas M.

Bergerd, Jean-Claude

Fauchèrea, , on behalf of the Swiss Neonatal End-of-Life Study Group

aDepartment of Neonatology, Perinatal Centre, University Hospital Zurich,

bInstitute of Biomedical Ethics and History of Medicine,

cDialogue Ethics Foundation,

dNeonatal and Paediatric Intensive Care Unit,

Sources of distress for physicians and nurses working in Swiss neonatal intensive care units

w14477

Summary

BACKGROUND

Medical personnel working in intensive care often face difficult ethical dilemmas. These may represent important sources of distress and may lead to a diminished self-perceived quality of care and eventually to burnout.

AIMS OF THE STUDY

The aim of this study was to identify work-related sources of distress and to assess symptoms of burnout among physicians and nurses working in Swiss neonatal intensive care units (NICUs).

METHODS

In summer 2015, we conducted an anonymous online survey comprising 140 questions about difficult ethical decisions concerning extremely preterm infants. Of these 140 questions, 12 questions related to sources of distress and 10 to burnout. All physicians and nurses (n = 552) working in the nine NICUs in Switzerland were invited to participate.

RESULTS

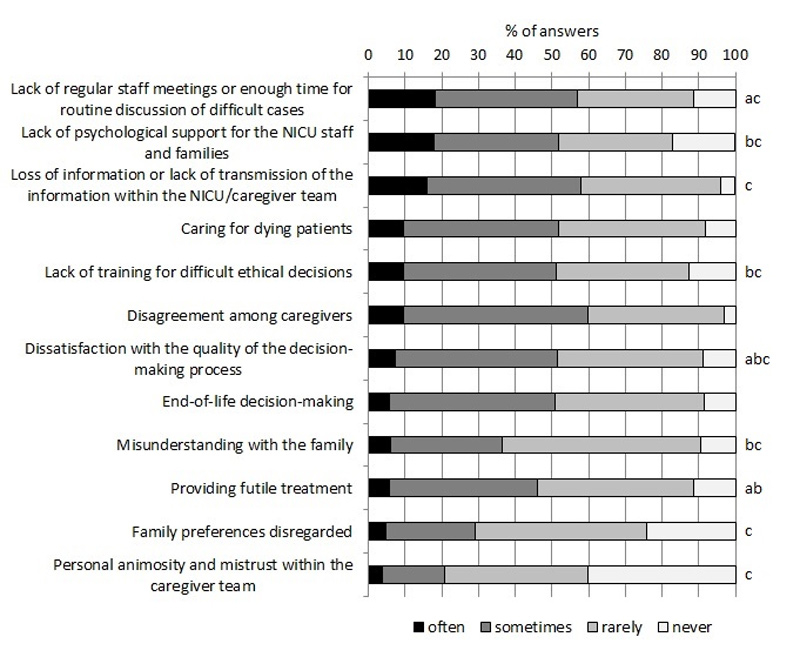

The response rate was 72% (398). The aspects of work most commonly identified as sources of distress were: lack of regular staff meetings, lack of time for routine discussion of difficult cases, lack of psychological support for the NICU staff and families, and missing transmission of important information within the caregiver team. Differences between physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions became apparent: for example, nurses were more dissatisfied with the quality of the decision-making process. Different perceptions were also noted between staff in the German- and French- speaking parts of Switzerland: for example, respondents from the French part rated lack of regular staff meetings as being more problematic. On the other hand, personnel in the French part were more satisfied with their accomplishments in the job. On average, low levels of burnout symptoms were revealed, and only 6% of respondents answered that the work-related burden often affected their private life.

CONCLUSIONS

Perceived sources of distress in Swiss NICUs were similar to those in ICU studies. Despite rare symptoms of burnout, communication measures such as regular staff meetings and psychological support to prevent distress were clearly requested.

Introduction

Difficult ethical questions and conflicts are commonly encountered by physicians and nurses working in intensive care units (ICUs) and may, together with working environmental factors, represent significant sources of distress. Uncertain or impaired decision-making capacity, disagreement among caregivers, and limitation of treatment at the end of life were the ethical difficulties most often reported by European physicians [1]. In a survey of ICU staff, 72% of the respondents reported at least one perceived conflict within the previous week [2]. Two groups of conflicts were identified: behaviour-related conflicts, i.e. personal animosity, mistrust or communication gaps, and conflicts around end-of-life care, i.e. lack of psychological support, absence of staff meetings, problems or dissatisfaction with the decision-making process.

Few studies have focused on neonatal ICUs (NICUs) and on potential sources of distress prevailing in this particular environment, although such problems were pointed out more than 35 years ago [3]. Personnel working in a delivery room reported insecurity in communicating with parents and providing emotional support in circumstances of primary palliative care as the most common source of distress [4]. Environmental factors, such as shortage of staff, were also named, but, interestingly, providing medical care to the patient was not mentioned. On the other hand, a recent systematic review described moral stress in NICUs and paediatric ICUs, namely inability to act according to one’s own moral judgement due to constraints, which occurred because of “doing too much” (aggressive use of technology, disproportionate interventions), sense of powerlessness, and communication around life and death issues [5].

Compared with the general working professions in the Unites States, physicians reported an increased risk of burnout and were less likely to be satisfied with their work-life balance. Burnout differed considerably between medical specialties, and practitioners in general paediatrics and paediatric subspecialties scored lower than average on burnout [6]. However, increased work stress and emotional exhaustion need to be addressed, since they have been linked to diminished self-perceived quality of care among hospital paediatricians [7]. A recent study even found an association between the perception of working too hard and increased healthcare-associated infection rates in very low birth weight neonates [8]. Thus, we aimed to identify possible sources of work-related distress and to assess symptoms of burnout within physicians and nurses working in Swiss NICUs.

Materials and methods

From June to August 2015, we conducted an online survey in collaboration with gfs-zurich (Market & Social Research) to explore the attitudes of neonatal physicians and nurses regarding difficult ethical decision making for extremely preterm infants in Switzerland. The whole questionnaire comprised 140 questions. One set of 12 closed questions sought to identify possible sources of distress that could occur during work (some of which had been previously identified [2]). One question asked how often the work-related burden affected the staff’s private life (possible answers: “often”, “sometimes”, “rarely” or “never”). Another 10 questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory [9] were also included; these were chosen according to their content and so that questions from each subscale were used. Factor analysis confirmed the correct allocation of the selected questions to the respective subscales. Questions about decision making and attitudes and values of neonatal physicians and nurses were adopted from the previously conducted EURONIC study [10].

All 121 physicians and 431 nurses working in the nine level III NICUs in Switzerland were invited to participate. Participation was voluntary, interviewees were asked for consent preceding the actual online survey, and responses were anonymised before analysis. The Ethics Committee of the Canton Zurich waived the need for approval of this survey.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Armonk, NY, USA). Results are presented as proportions or means with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Mann-Whitney U tests or Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to compare groups, since data were acquired on an ordinal (“often”, “sometimes”, “rarely”, “never”) or interval scale with non-normal distribution (0 = never, 6 = every day). A p-value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Of the 552 healthcare professionals invited to participate, 398 responded (response rate 72%). Seventy-nine percent of the physicians from the German-speaking part of Switzerland and 81% of the physicians from the French-speaking part answered the questionnaire. There was an underrepresentation of nurses from the French speaking part within the respondents: only 59% of the nurses from the French-speaking part responded, compared with 77% of the nurses from the German-speaking part (p <0.001).

Ninety-six (24%) of the respondents were physicians, 302 (76%) were nurses. The length of working experience in a NICU was ≤5 years for 138 healthcare professionals (35%), 6–15 years for 158 (40%), and >15 years for 101 (25%). A total of 284 (71%) of the respondents worked in the German-speaking part of Switzerland, and 114 (29%) in the French-speaking part.

The aspects of work most commonly identified as sources of distress were lack of regular staff meetings or insufficient time for routine discussion of difficult cases (18% answered that this occurred “often”), as well as lack of psychological support for the NICU staff and families (18%), and the loss of information or poor transmission of information within the NICU/caregiver team (16%; fig. 1). In contrast, family preferences were rarely disregarded and mistrust within the caregiver team rarely encountered. Nurses rated lack of regular staff meetings (U = ˗3.351, p = 0.001), dissatisfaction with the quality of the decision-making process (U = ˗ 3.241, p = 0.001), and providing futile treatment (U = ˗ 2.579, p = 0.01) as significantly more stressful than the physicians did. Besides, several of the listed burdens were reported less often with increasing work experience (lack of psychological support H(2) = 8.31, p = 0.016; lack of training H(2) = 20.17, p <0.001; dissatisfaction with the quality of the decision-making process H(2) = 9.15, p = 0.010; misunderstanding with the family H(2) = 7.67, p = 0.022; providing futile treatment H(2) = 11.01, p = 0.004) or among neonatal healthcare professionals working in the German speaking part of Switzerland (lack of regular staff meetings U = ˗4.933, p<0.001; lack of psychological support U = ˗5.701, p <0.001; loss of information U = ˗4.613, p <0.001; lack of training U = ˗5.890, p <0.001; dissatisfaction with the quality of the decision-making process U = ˗2.207, p = 0.027; misunderstanding with the family U = ˗4.778, p<0.001; family preferences disregarded U = ˗2.277, p = 0.023; personal animosity U = ˗3.375, p = 0.001).

When asked if the work-related burden affected their private lives, 6% of the respondents answered this was often the case, 36% said sometimes, 43% rarely and 15% never. Physicians’ private lives were significantly more often affected than nurses’ (U = ˗2.041, p = 0.041).

Questions from all three subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory (personal accomplishment, emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation) revealed that there was a low level of burnout among Swiss NICU personnel (tables 1, 2, 3

). Physicians felt significantly more frustrated in their job than nurses and were more likely to treat some patients as if they were impersonal objects, although over 70% of both professional groups answered that this was “never” the case (table 1). Longer work experience was associated with fewer signs of burnout, especially in the subscales of “emotional exhaustion” and “depersonalisation” (table 2). Healthcare professionals from the French-speaking region rated negative as well as positive aspects as occurring more often (table 3). Significant positive correlations were found between the questions from the subscale “emotional exhaustion” and the question about work-related burden affecting private life (feeling emotionally drained r = 0.409, p <0.001; feeling burned out r = 0.367, p <0.001; feeling fatigued when facing another day r = 0.299, p <0.001; feeling frustrated r = 0.272, p <0.001).

Table 1 Selected questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory: by profession.

|

Mean (95% confidence interval)*

|

p-value†

|

|

All

(n = 396)

|

Physicians

(n = 94)

|

Nurses

(n = 302)

|

|

| I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job‡

|

4.38

(4.23–4.53) |

4.57

(4.33–4.82) |

4.32

(4.13–4.50) |

0.508 |

| I feel very energetic‡

|

4.16

(4.01–4.31) |

4.32

(4.07–4.56) |

4.11

(3.93–4.28) |

0.580 |

| In my work, I deal with emotional problems very calmly‡

|

3.14

(2.93–3.35) |

3.38

(2.99–3.78) |

3.07

(2.83–3.31) |

0.258 |

| I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job§

|

1.96

(1.82–2.10) |

2.14

(1.86–2.42) |

1.91

(1.74–2.08) |

0.094 |

| I feel emotionally drained from my work§

|

1.35

(1.24–1.46) |

1.56

(1.31–1.82) |

1.29

(1.16–1.41) |

0.059 |

| I feel burned out from my work§

|

1.33

(1.21–1.45) |

1.53

(1.26–1.81) |

1.26

(1.13–1.40) |

0.123 |

| I feel frustrated by my job§

|

1.33

(1.22–1.44) |

1.56

(1.31–1.82) |

1.26

(1.14–1.38) |

0.037

|

| I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally¶

|

0.87

(0.75–0.99) |

0.80

(0.58–1.02) |

0.89

(0.74–1.04) |

0.895 |

| I don’t really care what happens to some patients¶

|

0.42

(0.32–0.52) |

0.43

(0.23–0.62) |

0.41

(0.30–0.53) |

0.457 |

| I feel I treat some patients as if they were impersonal objects¶

|

0.30

(0.22–0.38) |

0.47

(0.27–0.67) |

0.24

(0.16–0.32) |

0.010

|

Table 2 Selected questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory: by length of work experience.

|

Mean (95%confidence interval)*

|

p-value†

|

|

Length of experience

|

|

|

≤5 years

(n = 138)

|

6–15 years

(n = 156)

|

>15 years

(n = 101)

|

|

| I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job‡

|

4.15

(3.89–4.41) |

4.56

(4.32–4.79) |

4.41

(4.10–4.71) |

0.049

|

| I feel very energetic‡

|

4.28

(4.07–4.49) |

4.15

(3.91–4.39) |

4.01

(3.69–4.33) |

0.730 |

| In my work, I deal with emotional problems very calmly‡

|

3.26

(2.93–3.59) |

3.31

(2.99–3.62) |

2.70

(2.25–3.15) |

0.087 |

| I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job§

|

2.23

(1.98–2.48) |

1.93

(1.70–2.16) |

1.63

(1.37–1.89) |

0.006

|

| I feel emotionally drained from my work§

|

1.51

(1.30–1.73) |

1.32

(1.15–1.49) |

1.19

(0.99–1.39) |

0.161 |

| I feel burned out from my work§

|

1.58

(1.36–1.80) |

1.32

(1.12–1.52) |

0.99

(0.79–1.19) |

0.001

|

| I feel frustrated by my job§

|

1.52

(1.33–1.71) |

1.40

(1.21–1.59) |

0.98

(0.80–1.16) |

<0.001

|

| I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally¶

|

1.08

(0.88–1.28) |

0.99

(0.76–1.22) |

0.37

(0.20–0.53) |

<0.001

|

| I don’t really care what happens to some patients¶

|

0.61

(0.41–0.80) |

0.38

(0.23–0.54) |

0.21

(0.07–0.35) |

0.003

|

| I feel I treat some patients as if they were impersonal objects¶

|

0.54

(0.36–0.71) |

0.19

(0.11–0.26) |

0.13

(0.02–0.24) |

<0.001

|

Table 3 Selected questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory: by region.

|

Mean (95% confidence interval)*

|

p-value†

|

|

German speaking area

(n = 282)

|

French speaking area

(n = 114)

|

|

| I have accomplished many worthwhile things in this job‡

|

4.14

(3.96–4.32) |

4.97

(4.73–5.21) |

<0.001

|

| I feel very energetic‡

|

3.95

(3.78–4.13) |

4.67

(4.44–4.89) |

<0.001

|

| In my work, I deal with emotional problems very calmly‡

|

2.65

(2.41–2.89) |

4.37

(4.07–4.67) |

<0.001

|

| I feel fatigued when I get up in the morning and have to face another day on the job§

|

1.91

(1.74–2.09) |

2.09

(1.82–2.36) |

0.230 |

| I feel emotionally drained from my work§

|

1.25

(1.12–1.37) |

1.61

(1.38–1.85) |

0.005

|

| I feel burned out from my work§

|

1.08

(0.95–1.21) |

1.95

(1.71–2.18) |

<0.001

|

| I feel frustrated by my job§

|

1.15

(1.03–1.26) |

1.80

(1.56–2.04) |

<0.001

|

| I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally¶

|

0.67

(0.55–0.79) |

1.35

(1.05–1.65) |

<0.001

|

| I don’t really care what happens to some patients¶

|

0.34

(0.23–0.45) |

0.61

(0.40–0.83) |

0.002

|

| I feel I treat some patients as if they were impersonal objects¶

|

0.24

(0.16–0.32) |

0.43

(0.26–0.60) |

0.025

|

Discussion

Our study reveals that Swiss NICU personnel perceived the lack of routine discussions of difficult cases, lack of psychological support and poor transmission of information as more stressful than caring for very sick or dying newborn infants. This need for more structured professional exchange has previously been specified for ICU and delivery room settings [2–4], and, in a single-centre study, the introduction of an intensive communication strategy has even shown to reduce burnout amongst ICU caregivers [11].

In this survey, 42% of respondents reported that work-related burden often or sometimes affected their private lives, which is comparable to the 40% found in our previous pilot study [12] in which 74% of the neonatal health care providers indicated no physical complaints, psychosomatic symptoms or exhaustion. Hobbies and discussions with family and friends have been proposed and identified as main coping strategies to counterbalance distress at work [3, 4, 12]. Additionally, lower burnout rates were found in paediatric ICU staff who used “debriefing” or tried to “look for positives” [13].

Physicians and nurses often differ in their perceptions: for example, in French ICUs, the decision-making process was perceived as satisfactory by 73% of physicians but only 33% of nurses [14]. In our survey, 65% of physicians and 43% of nurses were satisfied with the quality of the decision-making process: this difference was smaller than in the French study, but still significant.

Distress and symptoms of burnout decreased with increasing work experience, possibly because experienced personnel were more often in leading positions with the capability of decision making and may have learnt to handle difficult situations better, or because physicians and nurses experiencing considerable problems on the job had resigned in earlier years of their career. A recent study investigated physician trainees’ experiences in NICUs [15]. The trainees experienced conflicts and distress while learning to care for critically ill and dying infants, and conflict was the most pervasive theme in their narratives.

Our survey revealed differences between the perceptions of personnel in the German- and French-speaking areas of Switzerland. These differences were not surprising, since they are noted in Switzerland in a variety of health-related topics. Interestingly, the answers in this survey were always more emotional in the French speaking part: positive items such as having accomplished worthwhile things in the job were rated more positively, while negative items were rated more negatively. In general, employees in the French-speaking areas have been shown to experience more work-related stress [16].

Strengths of this survey were that all Swiss NICU physicians and nurses were invited to participate and that a good response rate was achieved. Limitations include the fact that answers provided a self-reported and self-perceived view of the respondents, and no objective measures (e.g., days of absence due to illness) were used. Because of the length of the full questionnaire, only 10 questions from the Maslach Burnout Inventory could be employed, which limited comparability to other studies as we did not formally assess burnout.

From our results we conclude that perceived conflicts in Swiss NICUs were similar to those found in other studies. In contrast, personal animosity and mistrust occurred less commonly in our study. Several differences between physicians’ and nurses’ perceptions as well as between the two largest language regions in Switzerland regarding the lack of regular staff meetings or dissatisfaction with the quality of the decision-making process became apparent. Although single individuals may be at risk, on average low levels of burnout symptoms were found among Swiss NICU personnel. Nevertheless, communicative measures such as regular staff meetings and psychological support to prevent distress were clearly requested.

Appendix Members of the Swiss Neonatal End-of-Life Study Group

The Swiss Neonatal End-of-Life Study Group includes the following local coordinators (listed in alphabetical order of study site): Aarau: Neonatal Unit, Dept. of Paediatrics, Kantonsspital Aarau (Meyer Philipp, MD) – Basel: Neonatal Unit, University Children’s Hospital Basel UKBB (Neumann Roland, MD; Itin Renate) – Bern: Neonatal Unit, University Children’s Hospital, Inselspital (Nelle Mathias, MD; Stoffel Liliane) – Chur: Neonatal Unit, Dept. of Paediatrics, Kantonsspital Chur (Scharrer Brigitte, MD; Roloff Kai) – Geneva: Neonatology and Pediatric Intensive Care, Dept. of Paediatrics, University Hospital HCUG (Pfister Riccardo, MD) – Lausanne: Division of Neonatology, Dept. of Paediatrics, University Hospital CHUV (Roth Matthias, MD; Contino Magali) – Lucerne: Neonatal Unit, Children’s Hospital, Kantonsspital Luzern (Berger Thomas, MD; Schlegel Ulrike) – St. Gallen: Neonatal Unit, Children’s Hospital, Kantonsspital St. Gallen (Jaeger Gudrun, MD; Dutler Ruth) – Zurich: Department of Neonatology, University Hospital Zurich (Fauchère Jean-Claude, MD; Dinten Barbara).

*

Members of the Swiss Neonatal End-of-Life Study Group are listed in the appendix.

References

1

Hurst

SA

,

Perrier

A

,

Pegoraro

R

,

Reiter-Theil

S

,

Forde

R

,

Slowther

AM

, et al.

Ethical difficulties in clinical practice: experiences of European doctors. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(1):51–7. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2005.014266

2

Azoulay

E

,

Timsit

JF

,

Sprung

CL

,

Soares

M

,

Rusinová

K

,

Lafabrie

A

, et al.; Conflicus Study Investigators and for the Ethics Section of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(9):853–60. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC

3

Marshall

RE

,

Kasman

C

. Burnout in the neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 1980;65(6):1161–5.

4

Garten

L

,

Glöckner

S

,

Siedentopf

JP

,

Bührer

C

. Primary palliative care in the delivery room: patients’ and medical personnel’s perspectives. J Perinatol. 2015;35(12):1000–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2015.127

5

Prentice

T

,

Janvier

A

,

Gillam

L

,

Davis

PG

. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(8):701–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410

6

Shanafelt

TD

,

Hasan

O

,

Dyrbye

LN

,

Sinsky

C

,

Satele

D

,

Sloan

J

, et al.

Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023

7

Weigl

M

,

Schneider

A

,

Hoffmann

F

,

Angerer

P

. Work stress, burnout, and perceived quality of care: a cross-sectional study among hospital pediatricians. Eur J Pediatr. 2015;174(9):1237–46. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00431-015-2529-1

8

Tawfik

DS

,

Sexton

JB

,

Kan

P

,

Sharek

PJ

,

Nisbet

CC

,

Rigdon

J

, et al.

Burnout in the neonatal intensive care unit and its relation to healthcare-associated infections. J Perinatol. 2017;37(3):315–20. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.211

9Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. The Maslach burnout inventory: Manual. 3rd ed. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists; 1996.

10

Cuttini

M

,

Nadai

M

,

Kaminski

M

,

Hansen

G

,

de Leeuw

R

,

Lenoir

S

, et al.; EURONIC Study Group. End-of-life decisions in neonatal intensive care: physicians’ self-reported practices in seven European countries. Lancet. 2000;355(9221):2112–8. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02378-3

11

Quenot

JP

,

Rigaud

JP

,

Prin

S

,

Barbar

S

,

Pavon

A

,

Hamet

M

, et al.

Suffering among carers working in critical care can be reduced by an intensive communication strategy on end-of-life practices. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(1):55–61. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2413-z

12

Hauser

N

,

Natalucci

G

,

Bucher

HU

,

Klein

SD

,

Fauchère

JC

. Work-related burden on physicians and nurses working in neonatal intensive care units. Journal of Neonatology and Clinical Pediatrics.

2015;2(2):13.

13

Colville

G

,

Dalia

C

,

Brierley

J

,

Abbas

K

,

Morgan

H

,

Perkins-Porras

L

. Burnout and traumatic stress in staff working in paediatric intensive care: associations with resilience and coping strategies. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(2):364–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3559-2

14

Ferrand

E

,

Lemaire

F

,

Regnier

B

,

Kuteifan

K

,

Badet

M

,

Asfar

P

, et al.; French RESSENTI Group. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(10):1310–5. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200207-752OC

15

Boss

RD

,

Geller

G

,

Donohue

PK

. Conflicts in learning to care for critically ill newborns: “It makes me question my own morals”. J Bioeth Inq. 2015;12(3):437–48. doi:.https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-015-9609-9

16Grebner S, Berlowitz I, Alvarado V, Cassina M. Stress bei Schweizer Erwerbstätigen. Bern: Staatssekretariat für Wirtschaft; 2010.