Figure 1 The communication competence model (CCM) [31].

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2017.14427

The alarming prevalence of preventable patient safety incidents across the globe and the crucial importance of their disclosure to patients has been widely acknowledged. Numerous institutions now require open disclosure [1, 2], and the benefits are clear. Providers want to disclose errors to their patients [3], patients want to be informed [4–17], and ample evidence shows that effective disclosures facilitate positive outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions [4, 16, 18–22]. Despite this, the practice of disclosure remains rare [18, 23, 24]. The reasons for this gap are manifold. Providers commonly fear professional and legal sanctions [3, 5, 24] and lack the necessary knowledge and/or skills to conduct effective disclosures. Furthermore, they tend to perceive insufficient support from their institutions and colleagues to disclose adverse events to patients [25].

Even when disclosures take place, patients’ needs and expectations are often not met [19, 26–28]. Thus, it is not merely the disclosure, but how the disclosure is conducted that determines its effects [29, 30]. For example, it has been shown that an honest and remorseful disclosure decreases the likelihood of legal sanctions [14], and providers’ nonverbal involvement significantly predicts how patients react [20–22].

In sum, evidence has shown that competent communication is the medium through which positive disclosure outcomes can be attained. If providers communicate well with patients, disclosure outcomes can be enhanced. If disclosures are performed poorly, they induce a host of negative outcomes, ranging from distress, dissatisfaction, lowered trust and empathy, non-forgiveness, non-compliance and doctor-switching to patients’ pursuit of legal advice [20–22].

Communication science defines “competent communication” as goal-directed behaviours that lead to subjective impressions of appropriateness (i.e., legitimacy of behaviours to a given context and expectations) and effectiveness (i.e., ability of behaviours to achieve relatively rewarding outcomes in a given context) [31]. Thus, an error disclosure is competent if patients perceive the disclosing provider’s communication as both appropriate and effective. Based on this notion, appropriate and effective provider-patient communication during a disclosure is the pathway to mobilising patients’ competence impressions, which in turn facilitate beneficial disclosure outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions.

This implies that patient perceptions need to be the empirical starting point for informing the pathway that leads to beneficial rather than detrimental disclosure outcomes. For this reason, this study relied on focus groups with patients to gain greater insight into the behaviours, messages and contextual features of disclosures that patients generally perceive as both appropriate and effective, and that promote beneficial rather than detrimental outcomes.

This study pursued two novel objectives. First, numerous studies to date have investigated patients’ disclosure expectations with qualitative interviews and focus group designs. This study was the first to date to validate these findings in a new geographical context, in order to provide information on the extent to which current disclosure recommendations in the existing literature are applicable to Switzerland.

Second, this study was the first of its kind to apply and extend a predictive theoretical “communication competence model” (CCM) from the communication sciences to empirically inform the operational constituents of communicative competence in the context of medical error disclosures. In other words, this study provides a theoretical backbone to the existing literature, exploring the extent to which a communication science perspective may add to the current knowledge of interpersonal disclosure skills and solidify the pathway to effective disclosure outcomes. The study took an outcomes perspective to assess the quality of disclosures based on patients’ symptoms and behaviours following a disclosure. It considered these outcome measures as indicators of effectiveness, because patients’ symptomatic and behavioural health after a disclosure is a core concern for patients, providers, and healthcare institutions.

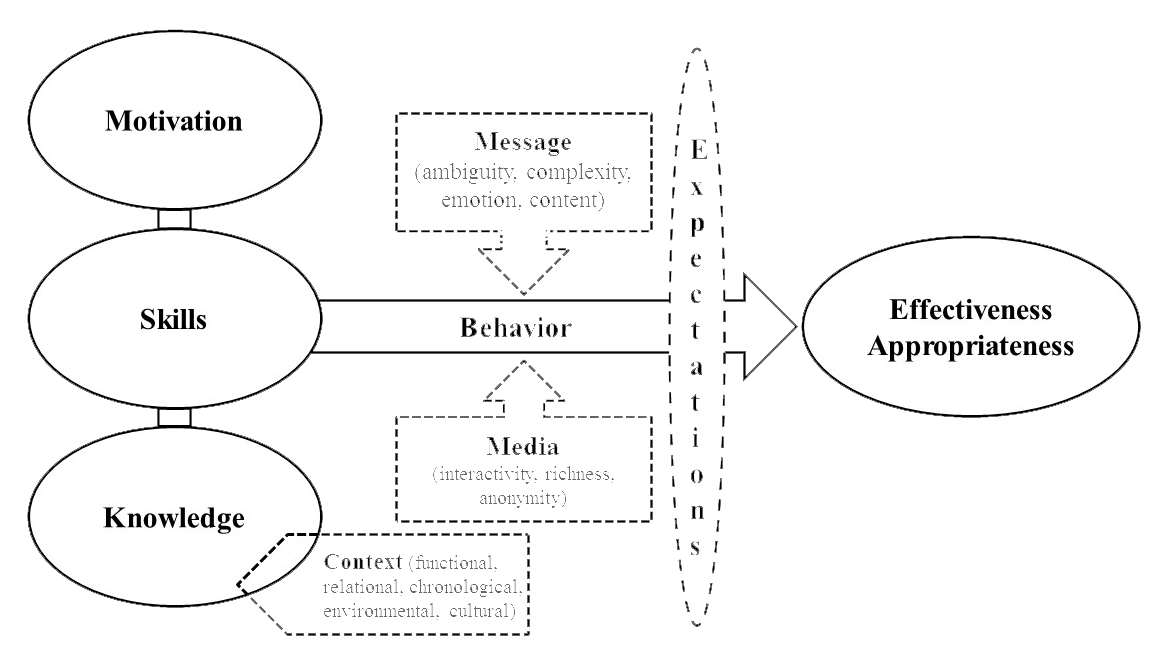

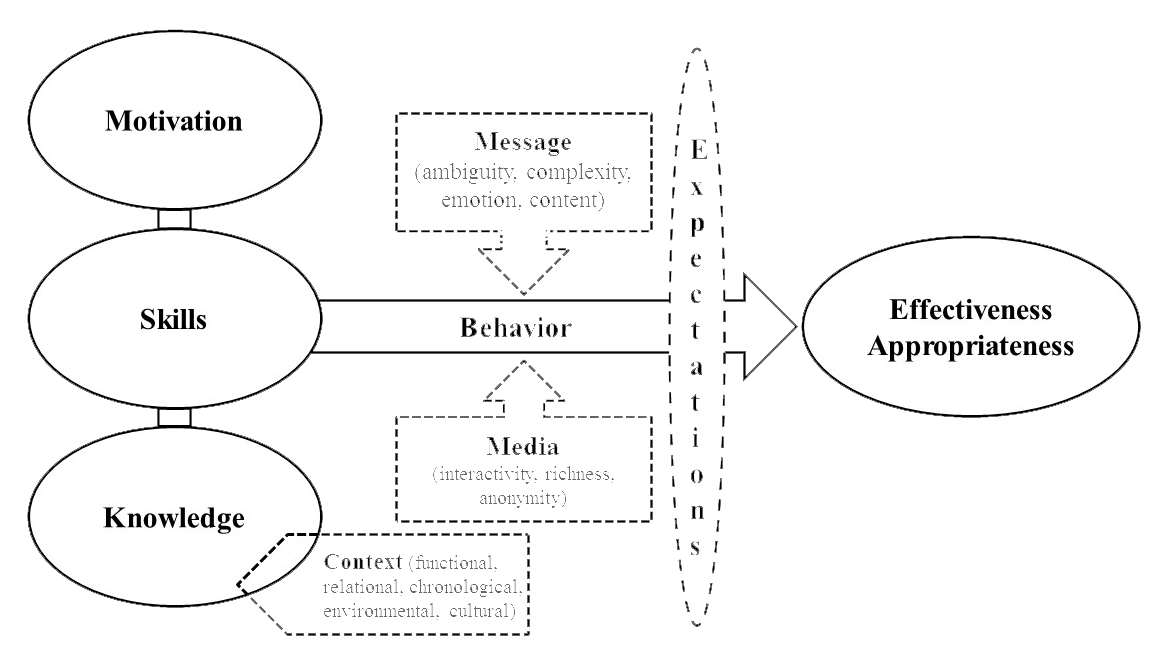

The communication competence model (CCM, fig. 1) is a core theoretical paradigm in the communication sciences. The model postulates that competence impressions are a function of each communicator’s motivation (rewards, costs), knowledge (symbols, roles, context), skills (attentiveness, composure, coordination, expressiveness), expectations and context. Context entails a number of dimensions: functional (e.g., compatibility of conversational objectives), relational (e.g., sense of connection, role interdependence, etc.), chronological (e.g., impositions of time in a given interaction), environmental (e.g., the physical environment and setting of a conversation) and cultural (e.g., rules, rituals, beliefs, and values of the interactants). Based on the CCM, motivation, knowledge, skills, expectations and context directly influence people’s impressions of a person’s communicative competence [31].

Figure 1 The communication competence model (CCM) [31].

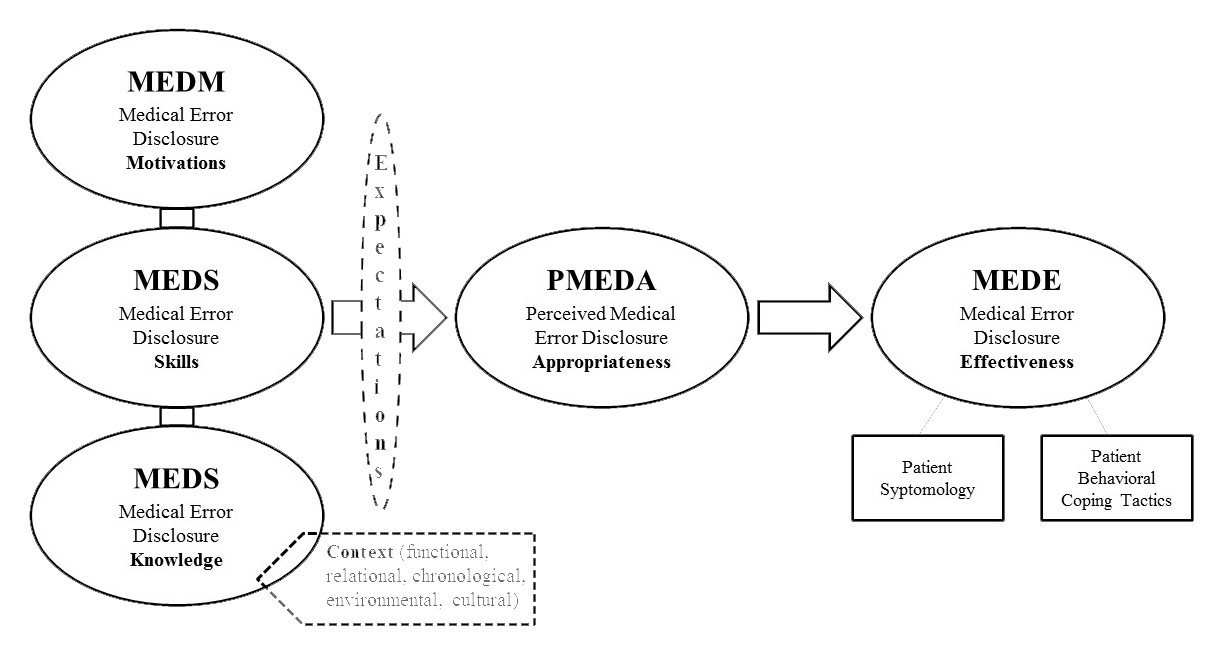

This study applies the CCM to the context of medical error disclosures and extends it to form a “medical error disclosure competence model” (MEDC, fig. 2). Like the CCM, the MEDC predicts that patients’ perceptions of a provider’s disclosure competence will vary as a function of the degree to which a provider has the motivation, knowledge and skills to disclose an error in a way that is perceived by patients as both appropriate and effective in the functional, relational, chronological, environmental and cultural context of the particular disclosure.

Figure 2 The new medical error disclosure competence (MEDC) model.

As an extension of the CCM, the MEDC proposes that appropriateness varies based on patients’ perceptions of the disclosing provider’s motivation, knowledge and skills, and that it functions as both a mediator and moderator of the relationship between disclosure skills and disclosure outcomes. Furthermore, the MEDC assesses effectiveness in terms of objective (rather than perceived) outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions, which are operationalised as patients’ actual symptomatic and behavioural responses to a disclosure (fig. 2).

Given the novelty of the MEDC model, its exploratory status, and the need to substantiate its constructs with empirical content, a number of research questions were proposed to characterise the variables in the hypothesised MEDC model. In particular, this study investigated the following research questions to provide information on Swiss patients’ expectations about providers’ motivation, knowledge, skills and context, as predicted by the MEDC:

As mentioned above, this study also aimed to empirically characterise the communication pathway that facilitates optimal disclosure outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions as predicted by the MEDC (fig. 2). The following research questions were proposed to assess disclosure outcomes (i.e., effectiveness) in terms of the symptoms and behaviours Swiss patients commonly experience and enact in response to a provider’s communicative (in)competence during a medical error disclosure:

As stated above, this investigation also aimed to evaluate the applicability of the existing literature on patients’ desired informational disclosure contents to a Swiss national context. For this objective, the following research question was proposed:

Patients were eligible to participate in this study if they were Swiss citizens, older than 18 years and able to provide written informed consent. Participants qualified as “patients” if they were “active users” of health care at the time of the study, defined as either (1) a hospitalisation within the past 3 years, (2) having a chronic illness, or (3) having a regular source of health care. This national data collection was approved by the ethics committees of all participating Swiss cantons.

A volunteer sample of patients was recruited with the help of the quality management staff of four university hospitals and two public hospitals in the German-, French-, and Italian-speaking parts of Switzerland. The staff distributed recruitment flyers with an attached registration form to current outpatients. The returned flyers were collected in locked boxes at each hospital’s outpatient clinics. The completed registration forms were returned by secure mail to the principal investigator. The self-registered patients were contacted by the principal investigator’s research assistants who validated their eligibility, gathered informed consent and scheduled the focus group meetings. Ten 90-minute focus group meetings were conducted at each hospital between July and November 2014. All patients were paid 20 Swiss francs for their participation.

Three research assistants (two doctoral students and one post-doctoral researcher) were hired and trained to conduct the focus groups at each participating hospital in the language of the respective geographical region. Three focus groups were held in the French-, three in the German- and four in the Italian-speaking cantons of Switzerland. To facilitate meaningful discussions, each focus group was limited to eight participants. Table 1 shows the standardised interview guide.

Table 1 Standardised focus group interview guide.

| Introductory round |

| 1. | Why – for you as a patient – is communication with your provider important to you? |

|---|---|

| 2. | What spontaneously comes to your mind when you hear the phrase “medical error disclosure”? |

| Part I: A hypothetical error disclosure | |

| Hypothetical error scenario (insulin overdose due to physician’s poor handwriting) | |

| 1. | Would you want to know about the error? |

| 2. | What would you expect from your doctor in the aftermath of such a medical error? |

| 3. | What amount of information would you have wanted to get from your doctor after this incident? |

| 4. | From your point of view, where should the disclosure of such an error take place? |

| 5. | How soon after the event should it have taken place? |

| 6. | With the responsible provider or someone else? |

| 7. | Alone, or with a third party? |

| 8. | What kind of behaviour of the physician would you have perceived as appropriate? |

| 9. | What kind of behaviour would have been inappropriate in your opinion? |

| 10. | Could you give a specific example of an optimal error disclosure -- what behaviours would make a physician’s error disclosure optimal? |

| 11. | Which behaviours would compromise the appropriateness of a physician’s error disclosure? |

| 12. | Imagine the error was caught before it harmed you. Would you still want to know about the error? |

| 13. | What about an event in which the error did reach you, but did not affect your health negatively. Would you still want to be informed about the error? |

| Part II: Actual experiences of a medical error disclosure | |

| Instruction: Patients who experienced an error in their care write down their experience | |

| 1. | Thinking about the person who disclosed the error to you: what behaviours did you perceive as appropriate? |

| 2. | What behaviours did you perceive as inappropriate? |

| 3. | Which aspects of the disclosure would you have changed, and why? |

| 4. | Reflecting on your individual events, what amount of information would you have wanted to obtain from your provider after the incident? |

| 5. | From your point of view, where should the disclosure have taken place? |

| 6. | How soon after the event should it have taken place? |

| 7. | With the responsible provider or someone else? |

| 8. | Alone or with a third party? |

| 9. | What kind of behaviour of the physician would have improved the disclosure? |

| 10. | What kind of behaviour of the physician would have compromised the disclosure? |

| 11. | Could you give a specific example of an optimal error disclosure -- what behaviors would make a physician’s error disclosure optimal? |

| 12. | Which behaviours would compromise the appropriateness of a physician’s error disclosure? |

| Closing round | |

| 1. | If you had the power to determine how physicians need to talk to patients after an error, what would you decide? |

| 2. | Is there anything else you would like to add? Did we forget anything important? |

The focus group discussions were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. For initial data reduction, one doctoral student and one post-doctoral researcher were hired and trained by the principal investigator to code the transcripts in their original language into broader context units (the largest units of text that needed to be included in the analysis, see [32]). The coded context units were then translated into English by each coder for further analysis by the principal investigator. The principal investigator coded the translated context units line-by-line into mutually exclusive recording units (see italicised labels of the exemplars in table 2). The recording units were then classified into the higher-level MEDC constructs (motivation, knowledge, skills, expectations, context, informational contents, outcomes) in accordance with a codebook based on the theoretical framework. Any recording units that did not classify into the higher-level MEDC categories were recorded in an “undefined” category for further thematic analysis. This category yielded several topic domains (e.g., handoffs, patient activation, privacy management, etc.) that reach beyond the scope of this study and thus are not elaborated in this paper.

Table 2 Coding categories and exemplars.

| Disclosure contents | ||

| Verbal apology | 1. Verbal enactment token: “I’m sorry,” “I apologise” 2. Source: doctors, nurses, and the hospital 3. Contents: in combination with an admission and explanation of the error |

|

| Responsibility | 1. Rationale: “they are no longer Gods in white;” “This is what makes physicians human – if they can admit an error;” “it can break aggressive reactions” 2. Admission as a core component of responsibility (versus cover-up/denial) 3. Admission and responsibility are inherently tied (e.g., “I really made a mistake”) 4. Source: it needs to come from “the boss, because he is responsible for his team, and I would like to see that” |

|

| Account | 1. What happened to this point in time (chronologically) 2. Why the patient is there 3. Why and how this could happen 4. What should have been done 5. What the patient needs to do now as a consequence of the error (e.g., adjusted behaviours/medication, etc.) 6. Consequences of the error 7. Corrective steps that will be taken 8. Performative sincerity of the account: “not that he pours it like a bucket onto the patient;” “deliver the information in a way that the situation can calm down” 9. Opportunity to ask questions |

|

| Remorse | 1. Apology: “it’s easy to apologise, but asking for forgiveness is something different;” “that I notice that the physician truly feels sorry;” “not that he only says tac-tac-tac, but that I can feel that he feels sorry” 2. Responsibility: “this wasn’t fake, he truly felt responsible for it;” “I can feel that he feels responsible, because he wants to know everything from A–Z” |

|

| Truthfulness | 1. Openness: “to talk to me openly;” “not rambling around” 2. Honesty: “he may need further exams and say ‘I made an error, but I don’t know why’, this is important” 3. Transparency: “if there is no clarity in the communication, the trust will be missing” 4. Authenticity: “it has to be on a level that feels and is completely authentic” |

|

| Diminution | 1. Ignorance: “the worst thing they can ever do is to pretend that nothing happened” 2. Arrogance: “but if they come highly arrogant and make everything seem half as bad, then it is twice as hard to forgive them” 3. Denial: “he continued to deny the error” 4. Lack of ethics: “it is one thing if the doctor doesn’t want to admit to himself that he made an error, but it is the right thing to inform the patient” |

|

| Reparation | 1. Process of reparation: “where can we go from here;” “what they will do about it;” “how things can be repaired” 2. Reparation of the patient’s health: “what can be done so that I feel better;” “how this can all be straightened out so that none of it remains and impacts my health” 3. Financial reparation (if justified): “if anything else needs to get done, it is covered by the institution;” “any extra costs will be taken care of” 4. Reparation of the patient’s professional life: “I am lying in intensive care and am unable to go to work – that he simply helps me in this situation, so I as the patient don’t have to communicate this to my employer on top of everything else, that the hospital did this to me” 5. Reparation of the patient’s psychological state: “maybe offer me some psychological support” |

|

| Future forbearance | 1. Investigation/reflection: “that people have stopped and thought about it, that solutions have been considered, I think this is very important” 2. Prevention: “that they consider, how can we prevent this from happening again next time?” 3. Learning/improvement: “that they draw consequences from it, to minimize future errors;” “because it allows us to say that the error didn’t happen for nothing, that it improved things;” “because it is much worse if you keep making errors” 4. Relational implications: “it shows that these people care for our health;” “if I don’t get this information, I would feel like the hospital doesn’t give a damn” 5. Content: “the doctor may not know, but he can say ‘other procedures will be put in place so that errors like this don’t happen again’, that would be comforting” |

|

| Medical error disclosure competence (MEDC) model | ||

| Motivation | Approach-oriented | 1. Relational establishment: building a close relationship as a foundation for mutual empathy 2. Relational maintenance: open door for the patient to revisit, so the patient doesn’t feel left alone with the error 3. Relational investment: “It would be somewhat of a compensation if the patient could revisit the physician in the future and say: ‘Listen, I have a problem.’” 4. Relational sincerity: “talk to you with the heart” 5. Relational recognition: “straighten things out for the patient” 6. Relational perspective-taking: empathy regarding the patient’s personal and professional life |

| Avoidance-oriented | 1. Relational avoidance: being unresponsive, disappearing, turning away 2. Identity separation: appearing snobbish, superiority, hiding behind medical terms 3. Defensiveness: tendency to attack to defend oneself |

|

| Knowledge | 1. Informational preferences: knowing about the patient’s participatory vs authoritarian care preference 2. Medical records/history: being informed about the patient’s entire care history 3. Individuality: knowing what type of person the patient is, knowing his/her wants |

|

| Skills | Attentiveness | 1. Physical barriers: a desk, stacked-up charts, or ringing phone are barriers to communication 2. Direct body orientation: sitting in front of the patient, face-to-face 3. Touch: “a hand on my shoulder” 4. Body lean: “that he takes a chair and leans over” 5. Eye contact: “eye-to-eye;” “that the physician looks at me when I talk;” “if one of them doesn’t look at me, I feel like they don’t even know I am here, that is very unkind” 6. Listening: “that I as the patient have the feeling that this person really listens to me, that his thoughts aren’t somewhere else” 7. Informational attentiveness: “that I have the feeling that he has made it a priority to be here with me to tell me what happened and why, not just en-passant” 8. Relational sensitivity: “empathy;” “that he gets into the skin of the patient;” “that the patient feels taken seriously;” “to seek personal contact with the patient;” “that there is a certain devotion, it is important that this comes across” 9. Proximity: sitting close but not too close to the patient, “it makes me uncomfortable if the physician remains close to the door instead of coming to my bed – it makes me feel like he is about to leave;” versus “I would not want too much closeness – he is the doctor, he is there, I am the patient, I am over here” |

| Composure | 1. Voice: a calm voice 2. Speed of talk: calmly explain what happened 3. Confidence: “to give confidence – saying ‘it’s going to be fine, don’t worry’ is comforting” |

|

| Coordination | Generating pauses to give patients an opportunity to react | |

| Expressiveness | 1. Voice: “a kind voice, for sure;” “an equal tone of voice” 2. Facial expressions: “a small smile when he comes in, we all need that when we’re sick” 3. Clarity: telling me in a very clear way;” “with a certain simplicity” 4. Emotional displays: “it should not get too emotional – informative and clear” |

|

| Interpersonal adaptability | 1. Shared decision-making: “I value when the doctor asks what I want so I can decide;” “I believe such decisions are situational – we can think about it now, but when it comes down to it, we may decide differently” 2. Features of the particular care episode: “appropriate, in that moment, is whatever meets the needs of the patient;” “it is difficult to find a universal solution – everyone reacts differently and perceived things differently;” “that’s completely individual;” “the doctor needs to feel out the patient;” “the doctor needs to notice how the patient reacts” 3. Language use: “not in pseudo-Latin;” “use simpler words, words we use outside the field of medicine;” “not in paragraphs and manuals, but with clear language;” “talk to me in a way that I can understand it – if I am only a housewife and a mother, then I would like that he speaks my language;” “you should come into my head – it’s not me, the patient, who has to enter the head of the doctor” 4. Information provision: “it is important to get a feel of how much information the patient needs so the patient doesn’t get overwhelmed;” “how much information a patient needs depends on each patient;” “the physician needs to provide information subtle and see how the patient reacts” 5. Nonverbal displays: “some patients don’t necessarily need a hand on their shoulder – others maybe more so” |

|

| Context | Functional | 1. Care companions: “four ears hear more than two” 2. Neutral third party: work up the error, validate the information 3. Written communication: so the patient can better understand and revisit the information 4. Health condition: “if I was on the intensive care station, I did not want to be occupied with such things;” “I really only need supporting words at that moment” |

| Relational | 1. Care companions: alleviate impact, emotional support 2. Neutral third party: safe environment; e.g., “If I tell him something that will upset him and he is going to take revenge against me and not treat me again, what am I going to do?”; “I shouldn’t be alone with the doctor, because I don’t trust a doctor who harmed me.” 3. Discloser: “whether it is the physician or a nurse makes no difference to me;” “the one who made the mistake – I would want to present my anger to the person who harmed me;” “I wouldn’t want to see that person, I wouldn’t want to have anything to do with him anymore;” “If the doctor can’t communicate well, it’s better if someone else does it” 4. Supervisor: “that the boss himself takes care of it” versus “he only attends to cover the physician (…), they help each other anyway” |

|

| Chronological | 1. Time allotment: “I should not feel like the doctor is in a hurry;” “that the person really shows that he takes and has the time to talk to me about this, without interruptions;” “something like this needs time to process – if the patient has questions later, there should be the opportunity to continue the conversation” 2. Timing: “that we can come back to it later,” “setting up a meeting for it, not in between two visits;” “disclosing in a moment that is already critical can aggravate the situation;” “I would want to be awake and responsive” 3. Timeliness: “immediately, because patients will notice very quickly that something is not right;” “the sooner the better;” versus “one should wait 2 or 3 days before disclosing, so that the body can recover from the error” |

|

| Environmental | 1. Number of people present: “the physicians should not outnumber the patient’s side;” “there were too many doctors (…) there was no doctor-patient communication in that moment” 2. Communication channel: “not over the phone” 3. Location: “in a medical practice” versus “no matter where” 4. Privacy level: “not in the patient’s bedroom with visitors present,” “not where other patients are around” versus “it would be even more honest if others hear it as well” |

|

| Cultural | No entries | |

| Medical error disclosure competence (MEDC) outcomes | ||

| Symptomology | Disturbance | 1. Sadness: “I would be sad.” 2. Disappointment: “I would be disappointed in the hospital and the physician.” 3. Hurt: “When you go to a doctor for over 25 years and he tells you that you’re the problem, that really hurts you.” |

| Affective health | 1. Distress: “I almost had a car accident, I was so distressed after the disclosure.” 2. Fear: “I spent three weeks thinking that I was going to die.” 3. Anger: “this is my life – I got irritated and aggressive.” |

|

| Cognitive health | 1. Sense of helplessness: “Then comes helplessness.” 2. Cognitive processing: “I would be able to better deal with it.” |

|

| Physical health | “I was in shock, I couldn’t breathe anymore” versus “much of my suffering was alleviated by the way in which the physician disclosed the error” | |

| Social health | “I can’t work anymore, and they cannot find a way to deal with it” | |

| Resource health | No entries | |

| Spiritual health | No entries | |

| Civic health | 1. Resignation: “there is no hope for justice;” 2. Lost trust: “I don’t trust them anymore” |

|

| Resilience | “That I remain in control, that would be comforting” | |

| Behaviours | Moving inward | “I was feeling some days that when I get out of the hospital, I am going to commit suicide” (–) “I was able to forgive the physician and come to terms with the situation” (+) |

| Moving outward | Involving a supervisor or third party to talk about the case if the disclosure was not sufficient | |

| Moving away | 1. Relational avoidance: “I never went to that doctor again;” “I am finished with my physician;” 2. Relational distancing: “I don’t let them touch me anymore if they don’t explain everything to me” |

|

| Moving toward/with | “I would respect this physician much more compared to physicians who cover up their error and blame it on someone else;” “I understood they make errors, so I learned to collaborate” | |

| Moving against | 1. Punishment/sanctions: “I would do everything for her to get sanctioned!” 2. Reputation damage: “Nobody goes to him because I talk about him.” 3. Legal procedures: “I filed a law suit.” |

|

In accordance with the MEDC, the coding scheme (see table 2) assessed providers’ disclosure motivations, knowledge, skills, context and expectations. Motivations were dichotomised into approach- and avoidance-oriented motivations. Knowledge was assessed as a unidimensional construct. Skills encompassed individual (attentiveness, composure, coordination, expressiveness) and dyadic (interpersonal adaptability) communication skills. The coding scheme operationalised all five a priori dimensions of context (functional, relational, chronological, environmental, cultural) and dichotomised patients’ expectations across two separate code sheets (expectations breached, expectations met).

As discussed above, this study took an outcomes perspective to evaluate the effectiveness of medical error disclosures. Such outcomes were analysed in terms of patients’ symptoms and behaviours in response to a disclosure.

Patients’ symptomatic outcomes were assessed on the basis of a typology of symptomology [33], which categorises symptoms (defined as “changes in health or life quality”) into (1) general disturbance (e.g., emotional or psychological), (2) affective health (e.g., anger, distress), (3) cognitive health (e.g., loss of self-esteem, sense of helplessness), (4) physical health (e.g., alcohol problems, drug abuse), (5) social health (e.g., relationship deterioration, work disruption), (6) resource health (e.g., financial cost), and (7) resilience (e.g., stronger self-concept).

Patients’ behavioural outcomes were categorised with a behavioural coping tactics scale [33] to assess patients’ behavioural reactions in terms of (1) moving inward (seeking self-improvement or insulation), (2) moving outward (seeking constructive assistance from others), (3) moving away (distancing oneself from the other, avoiding interaction with the other), (4) moving toward/with (constructively approaching the other, negotiating terms with the other), and/or (5) moving against (seeking/preparing to harm or incapacitate the other).

Ample studies have empirically substantiated the informational contents patients generally expect providers to discuss during an error disclosure [4, 5, 7, 12, 13, 17, 34–37]. To validate the applicability of these existing findings to Switzerland, the following categories were included in the coding scheme: verbal apology, responsibility, remorse, account, reparation, future forbearance, truthfulness and diminution.

Sixty-three patients participated in the ten focus group meetings. The patients were predominantly female (64%) and averaged 51 years of age, with their ages ranging from 22–80 years. The focus group characteristics are presented in table 3. The results discussed below are summarised in table 2.

Table 3 Characteristics of the focus groups.

| Patients (n = 63) | |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (range) | 50.67 (22–80) |

| Male, number (%) | 23 (36%) |

| Female, number (%) | 40 (64%) |

Patients expected providers to approach an error disclosure with the motivation to (1) establish a close, trusting relationship with their patient (as a foundation for mutual empathy), (2) maintain a relationship with their patient (opening the door for the patient to return in the future so the patient does not feel left alone with the error), and (3) invest in their relationship with the patient (demonstrating a willingness to “pay” for the error in “relational terms”). Patients also expected that providers approach them with a sense of (4) relational sincerity (taking the patient seriously, convey genuine respect), (5) relational recognition/reparation (e.g., recognising the impact of the error on the patient’s life, being motivated to straighten things out for the patient), and (6) relational perspective-taking (e.g., showing empathy, discussing implications of the error for the patient’s personal and professional life).

Patients judged providers as incompetent if they conveyed avoidance motivations during an error disclosure. Such motivations included (1) relational avoidance (e.g., if the provider was unresponsive, disappeared or physically turned away), (2) identity separation (e.g., if the provider appeared snobbish, accentuated superiority, hid behind technical terms), and (3) defensiveness (e.g., if providers had a tendency to defend themselves for the error).

Patients expected providers to demonstrate (1) understanding and awareness of the patient’s informational preferences (e.g., their participatory versus authoritarian care preferences), (2) informed knowledge of the patient’s medical history/records, and (3) recognition of the patient’s individuality (e.g., what type of person the patient is, what the patient wants and doesn’t want).

In regard to the functional context of disclosures, patients preferred the presence of (1) care companions (who could pick up information that patients may miss in a state of distress), (2) a neutral third party (who could help with working up the error, assessing the patient’s ability to understand the information and validating the information objectively), and (3) supplementary written communication (as an additional resource for patients to understand and later revisit the information). Patients also expected providers to consider their health condition (e.g., whether the patient is “present” enough to understand and digest the disclosed information, and whether a disclosure is “health-promoting” in the context of the patient’s condition).

Patients also discussed the relational context of a medical error disclosure. Patients preferred the presence of (1) care companions (who could lend emotional support), and (2) a neutral third party (external to the institution, who could help establish a trusting communication environment). Patients further discussed but did not find agreement on (3) who the discloser should be (the person who made the error or someone else), and (4) whether a supervisor should be present during the disclosure (i.e., the person in charge).

The chronological context of a competent medical error disclosure was also discussed. Patients raised the importance of providers’ (1) time allotment (allowing “plenty of time” without interruptions) and (2) timing of the disclosure (when the patient is responsive). Patients discussed but did not find agreement on the disclosure’s (3) timeliness (whether an error should be disclosed immediately versus “waiting 2–3 days” until the patient has recovered from the adverse event).

Patients expressed clear preferences regarding the environmental context of an appropriate medical error disclosure. They discussed the (1) number of people present at the disclosure (clinicians should not outnumber the patient’s side) and the (2) communication channel (“not over the phone”). Patients did not find agreement on the desired (3) location of a disclosure (“in a medical practice” versus “no matter where”) and the (4) privacy level of a disclosure (with or without visitors / other patients present).

No coded items categorised under cultural context.

Patients expected numerous communication skills from their providers in the context of a medical error disclosure.

Patients discussed providers’ distracting use of (1) physical barriers (e.g. a desk, stacked-up charts, a ringing phone), and the facilitating functions of (2) direct body orientation (sitting in front of the patient, face-to-face), (3) appropriate touch (e.g., “a hand on my shoulder”), (4) body lean (e.g., “that he takes a chair and leans over”), and (5) eye contact (e.g., “that the physician looks at me when I talk”). Patients also highlighted the importance of providers’ (6) listening (e.g., “that his thoughts aren’t somewhere else”), (7) informational attentiveness (e.g., “not just en-passant”), and (8) relational sensitivity (e.g., “that there is a certain devotion”). Patients discussed but did not find agreement on a proper (9) proximity (i.e., sitting close but not too close to the patient).

Patients clearly expected that providers effectively calm down the situation during a disclosure. Patients particularly discussed the importance of provider’s (1) tone of voice (e.g., a calm voice), (2) speed of talk (e.g., “calmly explain what happened”), and (3) confidence (e.g., “to give confidence – conveying ‘it’s going to be fine’ ”).

Only one coded item categorised under the skill cluster coordination. Patients discussed the importance of providers generating pauses to give patients opportunities to react.

Patients discussed the expressiveness of providers’ communication in respect to their appropriate use of (1) tone of voice (kind voice), (2) facial expressions (a small smile when entering the room), (3) clarity (clear and simple communication), and (4) emotional displays (not appearing too emotional).

Another desired communicative skill that emerged from the focus group data referred to providers’ ability to recognise and spontaneously adapt to patients’ ad-hoc expressed needs and expectations. Patients particularly discussed the importance of such interpersonal adaptability in respect to providers’ considerations regarding (1) shared decision making (sensitivity to patients’ ad-hoc decision-making preferences) and (2) features of the particular care context (e.g., “the doctor needs to see how the patient reacts”). Patients also expected interpersonal adaptability with regard to providers’ (3) language use (no medical jargon, adapting the language to the patient), (4) information provision (getting a feel of how much information the patient needs without getting overwhelmed), and (5) nonverbal displays (e.g., “some patients don’t necessarily need a hand on their shoulder – others maybe more so”).

In accordance with the existing literature, Swiss patients expected that providers assume responsibility for an error. Patients particularly (1) discussed the rationale behind this expectation (e.g., “this is what makes physicians human – if they can admit an error;” “it can break aggressive reactions”), (2) recognised admission as a core component of a responsibility declaration (because it prevents impressions of “cover-up” and denial), (3) suggested that admission and responsibility are inherently tied (e.g., “I really made a mistake”), and (4) highlighted that the source of responsibility statements matters (i.e., “it needs to come from the boss”).

Second, patients unanimously expected a verbal apology token from the provider (“I am sorry,” “I apologise”). They particularly discussed the importance of the apology’s (1) source (an apology needing to come from both the responsible clinicians and the hospital) and (2) contents (i.e., the apology needing to be delivered in combination with an admission and explanation of the error).

Third, patients expected that providers convey a full account of the medical error, including explanations of (1) what happened up to this point in time (chronologically), (2) why the patient is here, (3) why and how this happened, (4) what should have been done differently, and (5) what the patient needs to do now as a consequence of the error (e.g., adjusted behaviours / medication intake, etc.). Patients also expected a discussion of the (6) consequences of the error and (7) corrective steps that will be taken. Finally, patients discussed the importance of (8) performative sincerity of the account (e.g., “not that he pours it like a bucket onto the patient”), and (9) an opportunity to ask questions.

Patients discussed but could not find agreement on the (10) amount of information that should be given in the account (e.g., “it doesn’t have to go into full detail;” “I want to know every single detail so I don’t need to go to the internet to find out about possible complications;” “I first want to know the important stuff, and then return to the rest later”).

Patients expected that providers express remorse both in their (1) apology (e.g., “not that he only says tac-tac-tac, but that I can feel that he feels sorry”) and (2) responsibility declarations (e.g., “this wasn’t fake, he truly felt responsible for it”).

Furthermore, patients discussed four facets of truthfulness that they deemed important for error disclosures: (1) openness (e.g., “not rambling around”), (2) honesty (e.g., he may say that he needs further exams), (3) transparency (e.g., clear and straightforward communication), and (4) authenticity.

In the same vein, patients disliked three types of diminution: (1) ignorance (pretending that nothing happened), (2) arrogance (e.g., making everything seem half as bad), (3) denial (e.g., “he continued to deny the error”), and (4) a lack of ethics (e.g., disregarding the patient’s right to know).

Patients talked about five different types of reparation they expected providers to discuss during an error disclosure: (1) the process of reparation (how the consequences will be repaired), (2) reparation of their health (what will be done to make the patient feel better), (3) financial reparation (if justified, covering extra expenses), (4) reparation of their professional life (e.g., offering to talk to the patient’s employer), and (5) reparation of their psychological state (e.g., offering psychological support).

Patients also expected statements about future forbearance. They discussed that institutions need to actively engage in (1) investigation/reflection, (2) prevention, and (3) learning/improvement (drawing consequences to minimise future errors). Patients also discussed the (4) relational implications (e.g., “it shows that these people care for our health”), and (5) possible contents of a future forbearance declaration (e.g., “the doctor may not know, but he can say ‘other procedures will be put in place so that errors like this don’t happen again’”).

Patients raised numerous symptomatic consequences of incompetent error disclosures, all of which might have been alleviated – some even prevented – by a more competent disclosure. Patients’ symptoms ranged from general disturbance (sadness, disappointment, hurt feelings), affective health (distress, fear, anger), cognitive health (sense of helplessness, cognitive processing of the error), physical health (e.g., “I was in shock, I couldn’t breathe anymore” versus “much of my suffering was alleviated by the way in which the physician disclosed the error”), social health (e.g., “I am now permanently at the hospital, I cannot work anymore, and they cannot find a way to deal with it”), civic health (resignation and lost trust), to resilience (e.g., “that I remain in control, that would be comforting”). Surprisingly, patients did not discuss any effects of disclosures related to resource health (e.g., financial damages, time lost at work, etc.) and spiritual health (e.g., loss of faith in public systems, healthcare institutions, etc.).

As a direct result of incompetent error disclosures, patients reported (1) moving inward (e.g., “I was feeling some days that when I get out of the hospital, I am going to commit suicide”), (2) moving outward (involving a supervisor or third party to talk about the case if the disclosure was not sufficient), (3) moving away (relational avoidance and distancing), and (4) moving against the disclosing physician (punishment, sanctions, intentional reputation damage, legal procedures).

In response to competent error disclosures, patients reported (1) moving inward (e.g., “I was able to forgive the physician and come to terms with the situation”) and (2) moving toward/with the physician (e.g., “I would respect this physician much more compared to physicians who cover up their error and blame it on someone else;” “I understood they make errors, so I learned to collaborate”).

The objective of this study was twofold. First, this investigation aimed to evaluate the extent to which existing findings in the error disclosure literature regarding patients’ desired disclosure contents apply in the context of Switzerland. Second, this study applied and extended a competence model from the communication sciences to characterise the disclosure processes that facilitate optimal outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions.

This study provided evidence that patients in Switzerland generally expect similar informational contents during an error disclosure compared to patients in other countries (as discussed in previous studies [5, 19]). The findings of this first Swiss national investigation suggest that a “holy trinity” – evident in the combined conveyance of responsibility, apology and account – constitutes informational contents for an error disclosure that patients commonly perceive as both appropriate and effective, facilitating optimal disclosure outcomes for all involved care providers.

The findings of this study empirically characterise the operational contents of the proposed MEDC model constructs (fig. 2). Patients had clear expectations regarding their providers’ motivation, knowledge and communicative skills, as well as the extent to which providers adapt their communication to the context of the particular disclosure settings. These elements were identified as key determinants of patients’ competence perceptions.

This preliminary evidence implies that the MEDC model might be a fitting predictive framework rooted in communication science for characterising the pathway that leads to optimal disclosure outcomes. Given the qualitative focus of this initial exploratory investigation, this study does not warrant any causality inferences, but it lays the groundwork for future scale development and experimental testing of the MEDC model. Subsequent studies with more representative sample sizes are needed to examine the causal effects that are hypothesised on the basis of the model, with providers’ motivation, knowledge, skills and contextualisation predicting patients’ competence perceptions that, in turn, lead to (un)favourable disclosure outcomes. In other words, future studies need to examine the extent to which harmed patients’ perceptions of a disclosure as being appropriate will be effective in triggering optimal outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions, as assessed by patient’s symptoms and behaviours following a disclosure (see fig. 2).

The findings of this investigation add to and extend the body of existing work that already supports good disclosure in significant ways. In addition to describing the concrete communication skills that substantiate the pathway to facilitating positive disclosure outcomes, this study draws attention to the importance of considering the “grey zones” of medical error disclosures, particularly with regard to the amount of content that ought to be disclosed to patients. Given the findings of this study, a gradual disclosure might be a more competent alternative to an immediate full account. It is also important to feel out each patient’s personal needs and preferences for nonverbal comforting evident in providers’ use of proximity and touch. The findings of this investigation imply that patients will react differently to this kind of “tangible” nonverbal communication, suggesting that interpersonal adaptability is a critical communication skill for providers in the context of medical error disclosures to patients. Structural interventions can also be used to facilitate such interpersonal adaptability from an organisational perspective, for example, by proactively inquiring about patients’ preferences regarding when, where, and by whom an error should be disclosed in case of an unexpected event (table 4).

Table 4 Disclosure areas requiring provider’s and institution’s interpersonal adaptation.

| Prior to a disclosure, it would be important to determine: |

| 1. Patients’ preferences regarding who should disclose the error |

| 2. Timeliness (patients’ preferences regarding how soon the error should be disclosed) |

| 3. Location (patients’ preferences regarding where and how privately an error should be disclosed) |

| 4. Detail (the amount of detail a patient wants the disclosure to entail; also patients’ preferences for a gradual versus one-stop disclosure) |

| During the disclosure, it is important to feel out the following: |

| 1. Proximity (how close to sit to the patient during the disclosure) |

| 2. Touch (whether the patient needs a “hand on the shoulder”) |

| 3. Amount of information (amount of information a patient can digest during the disclosure without getting overwhelmed) |

The abovementioned “grey zone” implication constitutes a limitation that has constrained the interpretability and empirical value of many previous investigations in similar ways. A gradual disclosure implies that error disclosures involve multiple interactions. However, most studies to date that investigated error disclosures utilised retrospective and cross-sectional designs. Future investigations need to examine the communication processes as they develop over time and how they contribute to outcomes across numerous interactions.

Another limitation regards the “translatability” of the findings to an applied context that is multi-faceted, particularly with regard to diverse disciplines contributing valuable evidence to “good practice” recommendations. For example, the focus of the MEDC model on disclosure performance may be interpreted as “cheap grace” [38] by ethicists who regard the principles of ethical service as more important than facilitating patient perceptions to improve objective outcomes. In addition, the MEDC model starts with the well-being of the patient and only tangentially regards the “second victim” [39] perspective, by both (1) proposing that if a patient feels better and “behaves” optimally after a disclosure, then the “second victim” will also benefit from improved outcomes, and (2) regarding the context of a disclosure in the model (i.e., who should disclose the error). The model does not resolve the structural and emotional challenges that commonly inhibit disclosures.

These limitations illustrate the importance of disciplines needing to join rather than counter-argue their various “good practice” approaches to disclosing medical errors. As long as they cannot define a common ground in terms of measurable outcomes that matter equally to all stakeholders involved, this diversity of perspectives – much more so than any structural and skills challenges – will pose a critical barrier to improving practice.

The results of this investigation suggest that there is no “one-size-fits-all” approach to competent medical error disclosures. Thus, error disclosures do not lend themselves for a checklist approach. Instead, the findings of this study encourage a process that facilitates a cultural change and skills training approach. This study delivers two evidence-based starting points for such an intervention. First, patients agreed on a core set of behaviours and messages that contribute to perceptions of competent disclosures. Patients also expressed clear preferences regarding the contextual features of an error disclosure. These findings (summarised in table 5) can be used to design evidence-based disclosure training that is grounded in a predictive communication science model.

Table 5 Medical error disclosure competence (MEDC) training guidelines

| In preparation for the disclosure, take into account the following contextual considerations: |

| 1. | Decide whether the disclosure is beneficial to the patient’s health condition; if not, consider disclosing the error to a family member instead, or disclose it later when the patient is stable. |

|---|---|

| 2. | If possible, the patient should bring a care companion to the disclosure. |

| 3. | Invite a neutral (external) third party to the disclosure (as a person of trust for the patient). |

| 4. | Send the patient a written account after the disclosure so the patient can revisit and better understand the communicated information. |

| 5. | Make sure you schedule plenty of time for the disclosure (no time limit would be ideal). |

| 6. | Recognise the disclosure as a gradual, sequential conversation (there will be more than one meeting with the patient, the patient will need time to process and revisit the information). |

| DO NOT invite too many care participants to the disclosure – the number of clinicians should not outnumber the patients’ side. | |

| DO NOT disclose an error over the phone. | |

| Enter the disclosure with the motivation to: | |

| 1. | Establish a close, trusting relationship with the patient (as a foundation for mutual empathy). |

| 2. | Maintain a relationship with the patient (opening the door for the patient to return in the future). |

| 3. | Invest into the relationship with the patient (“paying for” the error in relational terms). |

| 4. | Demonstrate relational sincerity (take the patient seriously, convey genuine respect). |

| 5. | Straighten things out for the patient (e.g., in light of the error’s impact on the patient’s life). |

| 6. | Alleviate the implications of the error for the patient’s personal and professional life. |

| DO NOT appear avoidant, distant, or defensive. | |

| Enter the disclosure with informed knowledge about the patient’s: | |

| 1. | Informational preferences (i.e., participatory or authoritarian care style). |

| 2. | Medical history/records. |

| 3. | Personal preferences (e.g., what type of person the patient is, what the patient [doesn’t] want). |

| DO NOT enter any disclosure unprepared. | |

| During the disclosure, demonstrate the following communication skills: | |

| 1. | Attentiveness (sit in front or next to the patient; directly face the patient; occasionally lean toward the patient; make appropriate eye contact with the patient; look at the patient while s/he talks; show the patient that you are listening to him/her; show the patient that you have made it a priority to be here with him/her; seek personal contact with the patient and take his/her comments seriously; demonstrate a certain devotion to the patient’s needs; show the patient that you truly care for his health and well-being). |

| 2. | Composure (humbly try to calm down the situation; use a calm voice; calmly explain what happened; talk with calm confidence). |

| 3. | Coordination (pause appropriately to give the patient an opportunity to react) |

| 4. | Expressiveness (display a small smile when you enter the room; use a kind, equal tone of voice; talk to the patient very clearly; try to talk in simple terms; be empathic but do not get too emotional – remain informative and clear). |

| 5. | Interpersonal adaptability (spontaneously embrace needs or expectations that the patient expresses nonverbally or verbally ad-hoc; feel out the patient and see how the patient reacts; for example, be sensitive to the patient’s needs to decide something on his/her own; speak the patient’s language, check whether the patient understands what you are saying; try to enter the patient’s head; get a feel of how much information the patient needs so s/he does not get overwhelmed; see whether the patient needs a “hand on the shoulder”). |

| DO NOT introduce physical barriers to the conversation (e.g. a desk in between you and the patient, stacked-up charts, a ringing phone or beeper) | |

| DO NOT use technical language or medical terms that the patient may not understand | |

| During the disclosure, make sure to explicitly state the following contents: | |

| 1. | Be as open, honest, transparent, and authentic in your communication as possible. |

| 2. | Admit and assume responsibility for the error (e.g., “I really made a mistake”; if applicable, a statement of responsibility should also be conveyed by your supervisor). Make sure to express the responsibility with remorse. |

| 3. | All clinical attendees should state a verbal apology (i.e., “I am sorry,” “I apologise”; ideally, an apology should also be communicated from the hospital administration). Make sure to express the apology with remorse. |

| 4. | Provide an explanation of (a) what happened to this point in time (chronologically), (b) why the patient is here, (c) why and how this could happen, (d) what should have been done, and (e) if applicable, what the patient needs to do now as a consequence of the error (e.g., adjusted behaviours/medication intake etc.). Succinctly and clearly discuss the (a) consequences of the error and (7) corrective steps that will be taken. |

| 5. | Discuss what you will do / suggest doing next to correct the situation and/or repair the consequences of the error. |

| 6. | Discuss how you intend to repair the patient’s health (so that the patient feels better). |

| 7. | Offer the patient psychological support. |

| 8. | If applicable, offer the patient financial reparation (that any extra costs will be covered). |

| 9. | If applicable, discuss how you intend to repair the patient’s professional life (e.g., inform the patient’s employer). |

| 10.. | Ensure future forbearance by stating that you will actively engage in an investigation to reflect and draw consequences from this experience to prevent such errors in the future (conveying that the error didn’t happen for nothing, but that it led to improve things). |

| 11.) | Make sure to deliver the explanation succinctly, clearly, and with a calm voice. |

| 12.) | Give the patient an opportunity to ask questions. |

DO NOT ramble around the subject.

DO NOT ignore or deny the error.

DO NOT downplay the situation / make everything seem half as bad.

DO NOT display any arrogance whatsoever.

Second, there are aspects of disclosures on which patients did not agree (see table 4). As discussed above, these areas require interpersonal adaptability as an indispensable communication skill for competent disclosures. Interpersonal adaptability allows frontline providers to spontaneously respond to patients’ ad-hoc expressed needs and expectations in a way that patients will perceive as competent (effective and appropriate). It is also a relevant skill for institutions. For example, patients explicitly discussed that institutions might consider implementing a patient preference assessment at check-in to preliminarily document patients’ general disclosure preferences. The areas that require interpersonal adaptability, based on the results of this study, are summarised in table 4.

Patients clearly distinguished effects of competent versus incompetent disclosure communication on their symptomatic and behavioural outcomes. This study evidenced a broad array of such symptoms and behaviours. The measures that were used to assess patients’ outcomes in this investigation lend themselves as holistic assessment tools of patients’ post-disclosure experiences.

This study constitutes a first national investigation in Switzerland to evaluate the applicability of the existing literature on medical error disclosure to a Swiss context. It is also the first study to apply and extend a predictive model from the communication sciences to empirically describe what “competence” looks like in the context of medical error disclosures to patients. The findings of this investigation provide first evidence-based insights for a disclosure training programme that is rooted in communication science, focusing on communication skills as the pathway to facilitating optimal disclosure outcomes for patients, providers and healthcare institutions.

The author acknowledges Francesca Giuliani (USZ Zurich University Hospital), Linda Bourke Szirt (Basel University Hospital), Prof. Jean-Blaise Wasserfallen (CHUV Lausanne University Hospital), Adriana De Giorgi (EOC Ticino) and Dr Pierre Chopard (HUG Geneva University Hospital) for supporting the data collection in their respective cantons. The author also thanks Damian Rosset (PhD candidate, University of Neuchatel) and Zlatina Kostova (PhD, University of Massachusetts) for their support with the initial data reduction and translations.

This study was funded by a national research grant of the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project number 105312_146977).

1National Quality Forum. Safe Practices for Better Healthcare–2009 Update: A Consensus Report. Washington, DC: NQF; 2009.

2The Joint Commission. Comprehensive accreditation manual. CAMH for hospitals: the official handbook. Oakbrook Terrace, IL: Joint Commission; 2010.

3 Evans SB , Yu JB , Chagpar A . How radiation oncologists would disclose errors: results of a survey of radiation oncologists and trainees. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;84(2):e131–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.03.010

4 Mazor KM , Simon SR , Yood RA , Martinson BC , Gunter MJ , Reed GW , et al. Health plan members’ views about disclosure of medical errors. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(6):409–18. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-140-6-200403160-00006

5 Gallagher TH , Waterman AD , Ebers AG , Fraser VJ , Levinson W . Patients’ and physicians’ attitudes regarding the disclosure of medical errors. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1001–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.8.1001

6 Hammami MM , Attalah S , Al Qadire M . Which medical error to disclose to patients and by whom? Public preference and perceptions of norm and current practice. BMC Med Ethics. 2010;11(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-11-17

7 Hingorani M , Wong T , Vafidis G . Attitudes after unintended injury during treatment a survey of doctors and patients. West J Med. 1999;171(2):81–2.

8 Ushie BA , Salami KK , Jegede AS , Oyetunde M . Patients’ knowledge and perceived reactions to medical errors in a tertiary health facility in Nigeria. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(3):820–8.

9 Witman AB , Park DM , Hardin SB . How do patients want physicians to handle mistakes? A survey of internal medicine patients in an academic setting. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(22):2565–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.1996.00440210083008

10 Hobgood C , Peck CR , Gilbert B , Chappell K , Zou B . Medical errors-what and when: what do patients want to know? Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(11):1156–61.

11 Blendon RJ , DesRoches CM , Brodie M , Benson JM , Rosen AB , Schneider E , et al. Views of practicing physicians and the public on medical errors. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(24):1933–40. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa022151

12 Mazor KM , Goff SL , Dodd K , Alper EJ . Understanding patients’ perceptions of medical errors. J Commun Healthc. 2009;2(1):34–46. https://doi.org/10.1179/cih.2009.2.1.34

13 Bismark M , Dauer E , Paterson R , Studdert D . Accountability sought by patients following adverse events from medical care: the New Zealand experience. CMAJ. 2006;175(8):889–94. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060429

14 Wu AW , Huang I-C , Stokes S , Pronovost PJ . Disclosing medical errors to patients: it’s not what you say, it’s what they hear. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):1012–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1044-3

15 Hobgood C , Tamayo-Sarver JH , Elms A , Weiner B . Parental preferences for error disclosure, reporting, and legal action after medical error in the care of their children. Pediatrics. 2005;116(6):1276–86. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0946

16The Kaiser Family Foundation, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2006 Update on Consumers’ Views of Patient Safety and Quality Information. 2006. Available from: https://kaiserfamilyfoundation.files.wordpress.com/2013/01/7819.pdf

17 Espin S , Levinson W , Regehr G , Baker GR , Lingard L . Error or “act of God”? A study of patients’ and operating room team members’ perceptions of error definition, reporting, and disclosure. Surgery. 2006;139(1):6–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.07.023

18 White AA , Gallagher TH , Krauss MJ , Garbutt J , Waterman AD , Dunagan WC , et al. The attitudes and experiences of trainees regarding disclosing medical errors to patients. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):250–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181636e96

19 Iedema R , Allen S , Britton K , Piper D , Baker A , Grbich C , et al. Patients’ and family members’ views on how clinicians enact and how they should enact incident disclosure: the “100 patient stories” qualitative study. BMJ. 2011;343(jul25 1):d4423. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4423

20 Hannawa AF . “Explicitly implicit”: examining the importance of physician nonverbal involvement during error disclosures. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13576.

21 Hannawa AF . Disclosing medical errors to patients: effects of nonverbal involvement. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):310–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2013.11.007

22 Hannawa AF , Shigemoto Y , Little TD . Medical errors: Disclosure styles, interpersonal forgiveness, and outcomes. Soc Sci Med. 2016;156:29–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.03.026

23 Lander LI , Connor JA , Shah RK , Kentala E , Healy GB , Roberson DW . Otolaryngologists’ responses to errors and adverse events. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(7):1114–20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlg.0000224493.81115.57

24 Kaldjian LC , Jones EW , Wu BJ , Forman-Hoffman VL , Levi BH , Rosenthal GE . Disclosing medical errors to patients: attitudes and practices of physicians and trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):988–96. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0227-z

25 Wu AW , Boyle DJ , Wallace G , Mazor KM . Disclosure of adverse events in the United States and Canada: an update, and a proposed framework for improvement. J Public Health Res. 2013;2(3):e32. https://doi.org/10.4081/jphr.2013.e32

26 Chan DK , Gallagher TH , Reznick R , Levinson W . How surgeons disclose medical errors to patients: a study using standardized patients. Surgery. 2005;138(5):851–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.surg.2005.04.015

27 Mazor KM , Greene SM , Roblin D , Lemay CA , Firneno CL , Calvi J , et al. More than words: patients’ views on apology and disclosure when things go wrong in cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;90(3):341–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.07.010

28 Hannawa AF . Shedding light on the dark side of doctor-patient interactions: verbal and nonverbal messages physicians communicate during error disclosures. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(3):344–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.030

29 Vincent C , Young M , Phillips A . Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet. 1994;343(8913):1609–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(94)93062-7

30 Hickson GB , Clayton EW , Githens PB , Sloan FA . Factors that prompted families to file medical malpractice claims following perinatal injuries. JAMA. 1992;267(10):1359–63. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1992.03480100065032

31 Spitzberg BH . Axioms for a theory of intercultural communication competence. Annu Rev Engl Learn Teach. 2009;14:69–81.

32Krippendorff K. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2013.

33 Spitzberg BH . The tactical topography of stalking victimization and management. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2002;3(4):261–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838002237330

34The Conceptual Framework for the International Classification for Patient Safety. Version 1.1 Final Technical Report. Geneva: World Health Organization World Alliance for Patient Safety; 2009.

35 Keatings M , Martin M , McCallum A , Lewis J . Medical errors: understanding the parent’s perspective. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2006;53(6):1079–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2006.09.004

36Department of Health. Making Amends: A Consultation Paper Setting Out Proposals for Reforming the Approach to Clinical Negligence in the NHS. A Report by the Chief Medical Officer. London: Stationery Office, 2003.

37 Duclos CW , Eichler M , Taylor L , Quintela J , Main DS , Pace W , et al. Patient perspectives of patient-provider communication after adverse events. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(6):479–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzi065

38 Berlinger N . Avoiding cheap grace. Medical harm, patient safety, and the culture(s) of forgiveness. Hastings Cent Rep. 2003;33(6):28–36. https://doi.org/10.2307/3527823

39 Wu AW . Medical error: the second victim. The doctor who makes the mistake needs help too. BMJ. 2000;320(7237):726–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7237.726

This study was funded by a national research grant of the Swiss National Science Foundation (Project number 105312_146977).