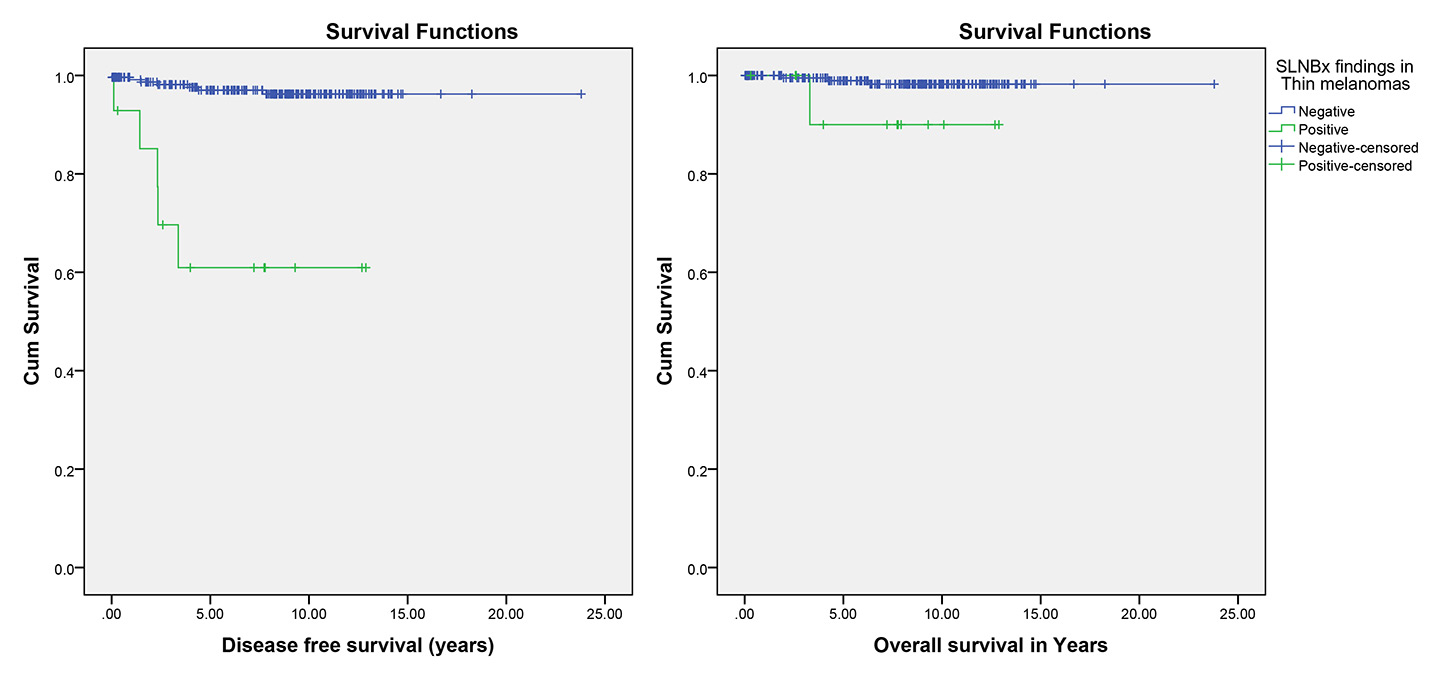

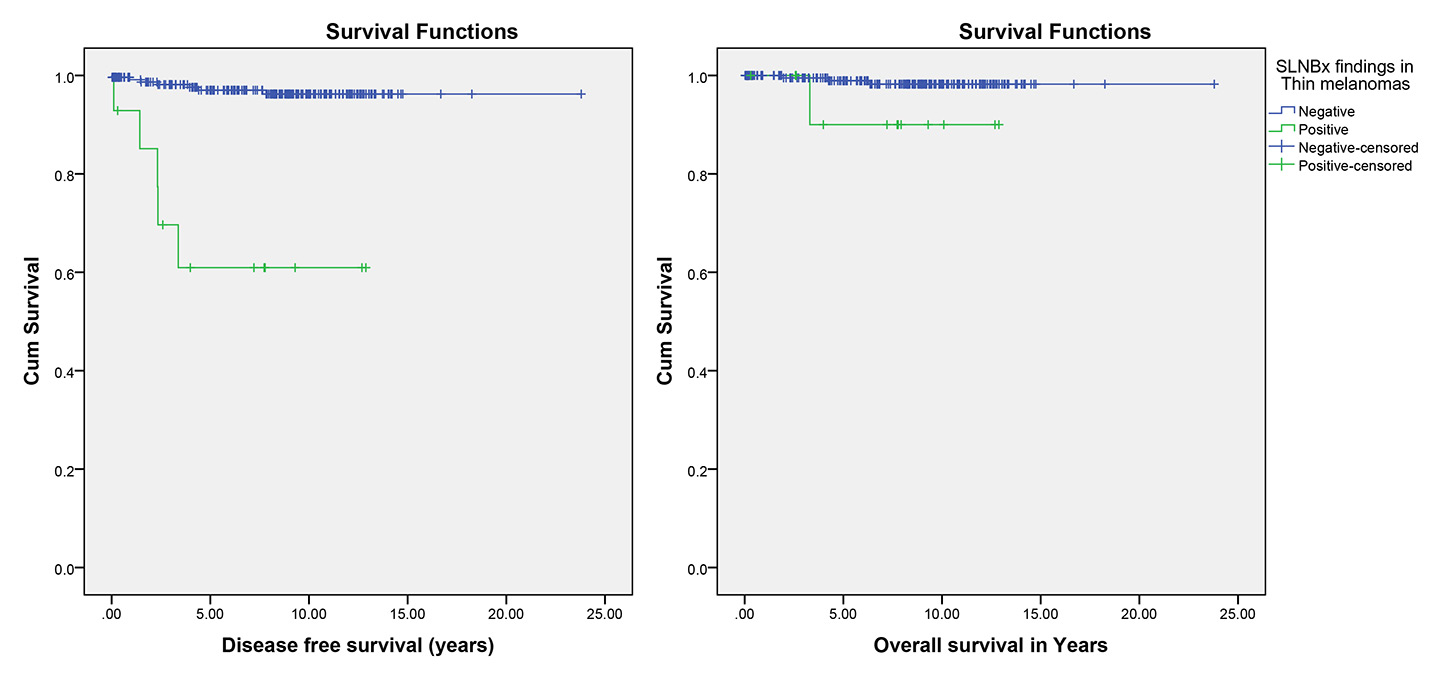

Figure 1

Effect of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBx) result on disease-free and overall survival in thin melanoma (p <0.001 and p = 0.077, respectively).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2016.14358

Malignant melanoma is a common type of skin cancer, which is potentially lethal if not diagnosed and excised at an early stage [1–3]. Although mortality rates have increased at a significantly lower rate, which has been attributed to improved early detection as evidenced by the diagnosis of thinner lesions over this time period [4, 5], its incidence continues to increase fastest of all cancers in Switzerland [6]. Since there is such a high incidence rate of melanoma, population-based data are important to improve early diagnosis and streamline screening programmes in local populations [3]. It is estimated that approximately 15 to 25% of patients with a clinically negative lymph node examination carry microscopic nodal metastases. As a result, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), which is the most sensitive and accurate investigative method for establishing regional node status in patients with melanoma, has gained rapid acceptance in the treatment of patients with melanoma [7–11]. However, its role and benefit in patients with melanomas of different Breslow’s thickness is still controversial [12]. As a result, the current study mainly aimed to evaluate the effect of lymph node biopsy results on disease-free and overall survival of patients with melanomas of different Breslow’s thickness.

We performed a retrospective cohort review of the melanoma database of patients from the University Hospital Bern, Switzerland. The study period was from 1990 to 2014, with the follow-up ending in 2015. All cases of single, primary localised cutaneous melanoma tumours were evaluated. Patients without complete medical records, documented surgical margins or regular follow-up were excluded from the study. All procedures were carried out in accordance with the standards of the ethical committee of the Canton of Bern, Switzerland (2016-00382), on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. Collected data consisted of patients’ gender, age, tumour location, tumour type, Breslow’s thickness, ulceration and SLNB result. In addition, locoregional recurrence, distant metastases, disease-free and overall survival were used as the crucial parameters to compare outcome between the study groups.

In this study, the lesions were categorised into thin (≤1.0 mm), Intermediate (1.0–4.0 mm) and thick melanomas (≥4.0 mm) [13]. Additionally, locoregional recurrence after primary excision was considered to include recurrence locally at the site of the primary lesion, regionally in the draining lymph node basin, and/or anywhere in between [11, 14–16]. Spread from primary tumour to distant lymph nodes or distant organs was defined as distant metastasis [17–19].

All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 21.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, U.S.A.). All p-values relate to a two-sided test with an α level of 0.05. For categorical and continuous characteristics, χ2-test, Fisher’s exact test and analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to detect possible differences among the study groups. Disease-free and overall survival were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. For disease-free survival, patients confirmed to be without locoregional recurrence or distant metastasis were censored using their last contact date. For overall survival, patients confirmed to be alive were censored using their last contact date. The confidence interval (CI) of hazard ratios (HRs) for Cox regression and overall survival (for time-to-event variables) were calculated. The p-value based on log rank (Mantel-Cox test) was used to check if the study groups had different disease-free and overall survival functions. The Cox proportional hazard model was used to estimate the bivariate association between each endpoint and the available patient/tumour characteristics. Prognostic factors considered for the multivariate Cox analysis of the primary melanomas were age, gender, tumour thickness, ulceration and positive SLNB [9, 20, 21]. A p-value<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Between 1990 and 2014, 1111 patients (527 female, 584 male; mean age 64.33 ± 15.44 years) with single, primary localised cutaneous melanoma tumours were considered in the analyses in this study, with mean follow-up of 22 77.3 days.

Figure 1

Effect of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBx) result on disease-free and overall survival in thin melanoma (p <0.001 and p = 0.077, respectively).

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) Breslow’s depth of the study patients’ primary melanoma tumours was 1.92 ± 2.70 mm (0.09–45 mm). A total of 179 (16.1%) of our study patients had ulceration in their tumours. Superficial spreading melanoma was the most frequent (48.6%) and amelanotic melanoma the least frequent (0.5%) tumour type. Furthermore, the trunk area was the location of the highest number of primary tumours (40.0%). For 889 (80.0%) patients, SLNB was performed. Of the melanomas evaluated, 464 (41.8%) were thin, 523 (47.0%) intermediate and 124 (11.2%) thick. As presented in table 1, statistical analysis showed no significant differences between the patients in the different thickness groups regarding age, gender and melanoma location. However, the incidence of ulceration, positive sentinel lymph node biopsies, metastasis and death increased significantly with the thick melanomas (p<0.001). Furthermore, the multivariate Cox analysis showed that age, ulceration, Breslow’s depth and SLNB result significantly influenced disease-free survival. This analysis also showed that age, gender, ulceration, Breslow’s depth and SLNB result significantly affected overall survival (table 2).

Ten (2.2%) patients with thin melanoma had locoregional recurrence and 15 (3.2%) had distant metastases, which were significantly more frequent in the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.007 and p = 0.003; respectively). However, although the death attributed to melanoma was more frequent in the patients with positive SLNB, this difference was not statistically significant (p= 0.187; tables 1 and 3). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier methods showed that the patients with negative SLNB had better disease-free survival than the patients with positive SLNB (p<0.001). Although mean overall survival time of the patients with positive SLNB (11.92 years, 95% CI 10.14–13.71) was less than in the patients with negative SLNB (23.45 years, 95% CI 23.06–23.84), this difference was not significant (p= 0. 077; table 4, fig. 1).

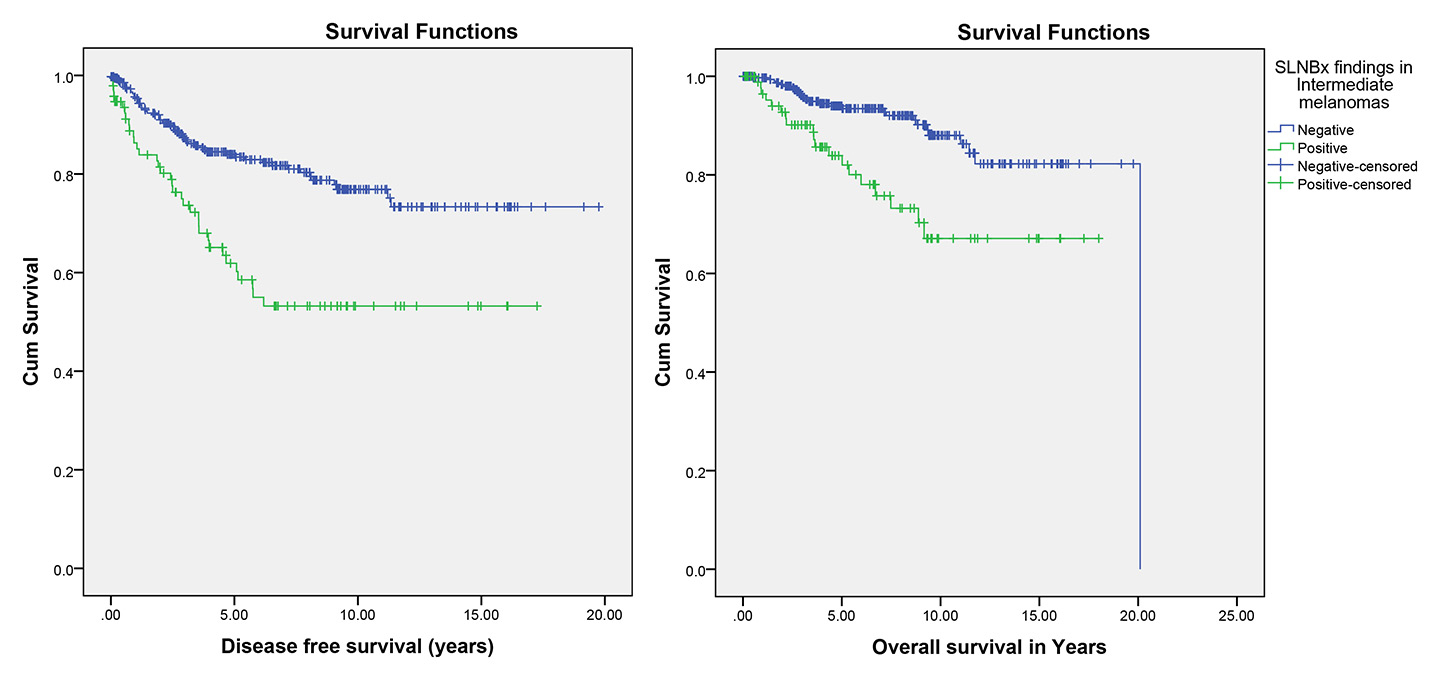

Locoregional recurrence, distant metastases and death attributed to melanoma occurred in 74 (14.1%), 69 (13.2%) and 51 (9.8%), respectively, among the patients with intermediate melanomas, and were significantly more frequent in the patient with positive SLNB (p <0.001; tables 1 and 3). Additionally, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed significantly better disease-free and overall survival in the patients with negative SLNB than in the patients with positive SLNB (p <0.001; table 4, fig. 2).

Figure 2

Effect of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBx) result on disease-free and overall survival in intermediate melanoma (p <0.001 and p <0.001, respectively).

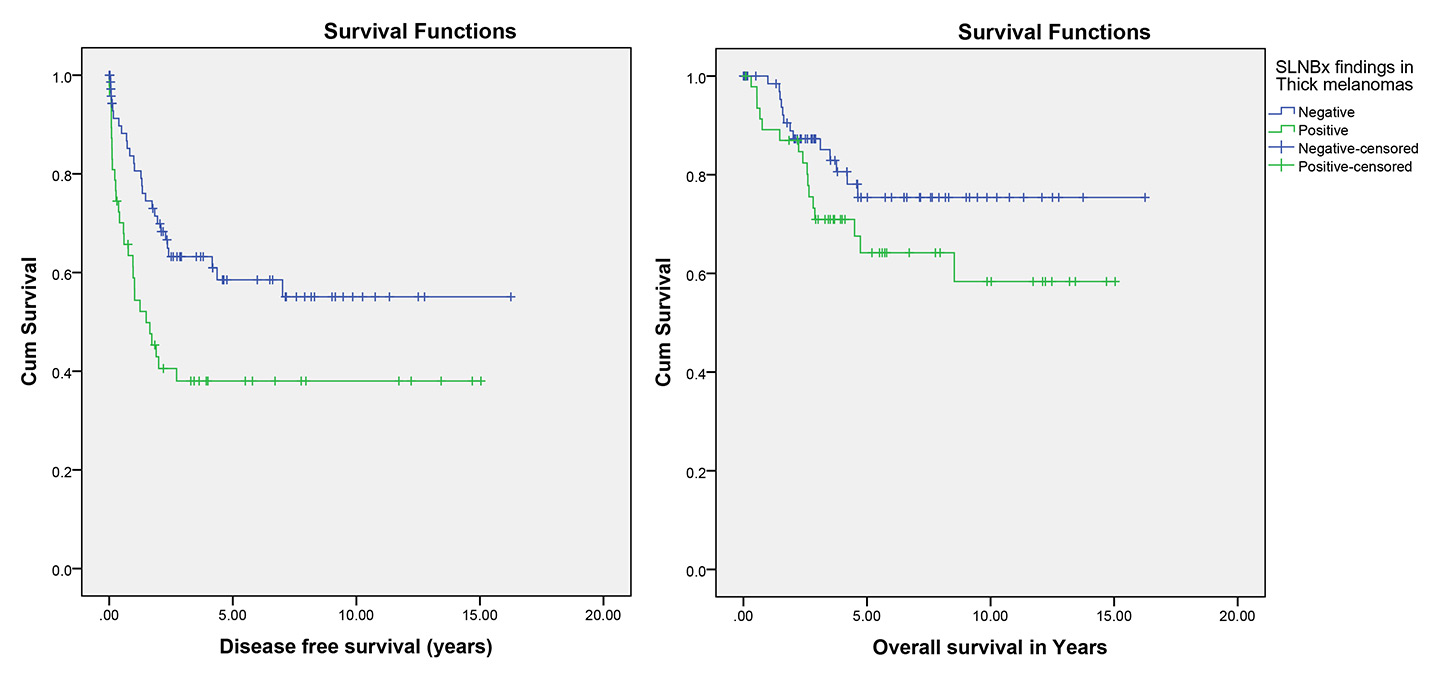

Figure 3

Effect of sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBx) result on disease-free and overall survival in thick melanoma (p = 0.008 and p = 0.13, respectively).

Evaluation of thick melanomas showed 41 (33.1%) patients with locoregional recurrence, 41 (33.1%) with distant metastases and 29 (23.4%) with death attributed to melanoma, which were significantly more frequent in the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.001, 0.017 and 0.05; respectively; tables 1 and 3). In addition, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed significantly better disease-free survival in the patients with negative SLNB than in the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.008). However, despite worse mean overall survival in the patients with positive SLNB (10.10 years, 95% CI 8.16–12.03) compared with the patients with negative SLNB (12.91 years, 95% CI 11.30–14.52), this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13; table 4, fig. 3).

| Table 1:Patients and tumour characteristics according to melanoma thickness. | |||||

| Characteristics | Melanoma group | p-value | |||

| Thin | Intermediate | Thick | |||

| Gender (no./%) | Female | 225 (48.5) | 254 (48.6) | 48 (38.7) | 0.119 |

| Male | 239 (51.5) | 269 (51.4) | 76 (61.3) | ||

| Age (Years) | Mean ± SD | 64.0 ± 15.3 | 64.6 ± 15.7 | 64.1 ± 14.6 | 0.819 |

| Median | 64.0 | 66.0 | 67.0 | ||

| Breslow (mm) | Mean ± SD | 0.6 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 6.9 ± 5.6 | – |

| Median | 0.6 | 1.6 | 5.2 | ||

| Melanoma site (no./%) | Head and Neck | 67(14.4) | 65 (12.4) | 27 (21.8) | 0.059 |

| Trunk | 196 (42.2) | 200 (38.2) | 48 (38.7) | ||

| Upper Extremity | 73 (15.7) | 104 (19.9) | 15 (12.1) | ||

| Lower Extremity | 128 (27.6) | 154 (29.4) | 34 (27.4) | ||

| Melanoma Type (no./%) | NM | 48 (10.3) | 246 (47.0) | 89 (71.8) | <0.001 |

| SSM | 329 (70.9) | 193 (36.9) | 18 (14.5) | ||

| Others | 87 (18.8) | 84 (16.1) | 17 (13.7) | ||

| Ulceration | 14 (3.0) | 107 (20.5) | 58 (46.8) | <0.001 | |

| Positive SLNB | 14 (5.0) | 95 (19.3) | 47 (38.8) | <0.001 | |

| Locoregional recurrence | 10 (2.2) | 74 (14.1) | 41 (33.1) | <0.001 | |

| Distant metastases | 15 (3.2) | 69 (13.2) | 41 (33.1) | <0.001 | |

| Death attributed to melanoma | 11 (2.4) | 51 (9.8) | 29 (23.4) | <0.001 | |

| NM = nodular melanoma; SD = standard deviation; SLNB = sentinel lymph node biopsy; SSM = superficial spreading melanoma | |||||

| Table 2:Cox analysis based on melanoma thickness. | ||||

| Factors associated with disease-free survival | Factors associated with overall survival | |||

| Variable | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) |

| Age | 0.001 | 1.019 (1.008–1.031) | <0.001 | 1.033 (1.017–1.051) |

| Sex | 0.452 | 0.885 (0.643–1.217) | 0.004 | 0.466 (0.276–0.784) |

| Ulceration | <0.001 | 0.430 (0.306–0.604) | 0.016 | 0.537 (0.325–0.889) |

| Positive SLNB | <0.001 | 0.310 (0.220–0.435) | <0.001 | 0.295 (0.180–0.483) |

| Breslow thickness | <0.001 | 1.098 (1.072–1.124) | <0.001 | 1.080 (1.049–1.111) |

| CI = confidence interval; SLNB = sentinel lymph node biopsy | ||||

| Table 3: The association between sentinel lymph node biopsy result and clinical outcomes in patients with melanomas of different thickness. | |||||||||

| Thin melanoma | Intermediate melanoma | Thick melanoma | |||||||

| Variable | Negative SLNB | Positive SLNB | p-value | Negative SLNB | Positive SLNB | p-value | Negative SLNB | Positive SLNB | p-value |

| Locoregional recurrence (no./%) | 6 (2.3) | 3 (21.4) | 0.007 | 40 (10.0) | 25 (26.3) | <0.001 | 16 (21.6) | 24 (51.1) | 0.001 |

| Distant metastases (no./%) | 4 (1.5) | 3 (21.4) | 0.003 | 36 (9.0) | 28 (29.5) | <0.001 | 18 (24.3) | 22 (46.8) | 0.017 |

| Death attributed to melanoma (no./%) | 3 (1.1) | 1 (7.1) | 0.187 | 27 (6.7) | 19 (20.0) | <0.001 | 13 (17.6) | 16 (34.0) | 0.05 |

| Table 4: The association between sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) result and clinical outcomes in patients with different melanoma thicknesses. | |||||||||

| Melanoma thickness group | SLNB result | Mean disease-free survival (years) | Mean overall survival (years) | ||||||

| Estimate | Std. error | 95% confidence interval | Estimate | Std. error | 95% confidence interval | ||||

| Lower bound | Upper bound | Lower bound | Upper bound | ||||||

| Thin | Negative | 23.03 | 0.29 | 22.47 | 23.59 | 23.45 | 0.20 | 23.06 | 23.84 |

| Positive | 8.62 | 1.50 | 5.68 | 11.57 | 11.92 | 0.91 | 10.14 | 13.71 | |

| Intermediate | Negative | 15.73 | 0.49 | 14.77 | 16.68 | 17.84 | 0.45 | 16.96 | 18.73 |

| Positive | 10.46 | 0.86 | 8.77 | 12.15 | 13.68 | 0.85 | 12.01 | 15.34 | |

| Thick | Negative | 9.80 | 0.95 | 7.93 | 11.67 | 12.91 | 0.82 | 11.30 | 14.52 |

| Positive | 6.20 | 1.04 | 4.15 | 8.25 | 10.10 | 0.99 | 8.16 | 12.03 | |

The use of SLNB for accurate disease staging is a key part of the early detection of occult metastatic disease in the regional lymph nodes and the preliminary management of many people with localised melanoma [22–25]. However, it is not uniformly accepted at all specialised centres as the standard of care as a result of the important controversy relating to its usefulness (therapeutic efficacy, safety and costs) [22, 25]. However, our study on different melanoma groups indicated that a positive SLNB is associated with worse outcomes in melanoma patients, regardless of melanoma thickness. In this study, multivariate Cox analysis found that age, ulceration, Breslow’s depth and SLNB result significantly decreased disease-free survival. Others have also reported the impact of SLNB status [12, 26–28], ulceration [12, 26, 27], and increased Breslow’s thickness [12, 28, 29] on disease-free survival. This analysis also demonstrated that age, gender, ulceration, Breslow’s depth and SLNB result significantly affected overall survival; previous reports have concluded that the overall survival of patients with thick melanoma was affected by SLNB status [26–28], ulceration [27, 28], and increased Breslow’s thickness [12, 26, 28].

The overall incidence of a positive SLNB in thin melanoma in prior studies has ranged from 0 to 7.8% but the studies differed in their definition of thin melanoma and inclusion criteria [25, 30–35]. Similarly, positive SLNB was detected in 5.0% of our patients. Some authors have suggested that SLNB is not useful unless it can be shown to improve survival, because thin primary melanoma has a 96% survival rate after 20 years of follow-up [36, 37]. However, other authors demonstrated sentinel node metastases as the single most important prognostic indicator in patients with melanoma [36, 38, 39]. Of the patients with thin melanoma, 10 (2.2%) with locoregional recurrence and 15 (3.2%) with distant metastases were observed, and there were significantly more among the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.007 and p = 0.003, respectively). Furthermore, Kaplan-Meier methods interestingly showed that the patients with negative SLNB had better disease-free survival than the patients with positive SLNB (p <0.001).

Our findings provide support for previous analyses [25, 39, 40], which showed that disease-free survival is significantly associated with SLNB results in patients with thin melanomas. Nevertheless, Wong et al. [41] did not find a significant difference between thin melanomas with positive and negative sentinel lymph nodes regarding disease-specific survival (p = 0.77). Although mean overall survival time in the patients with positive SLNB was less than the patients with negative SLNB, this difference was not statistically significant (p= 0.077) in our study. However, in the recent studies, the importance of sentinel node status in overall survival of melanoma patients was supported, since thin melanomas with positive SLNB had significantly poorer prognosis [25, 39, 40, 42].

The incidence of a positive SLNB in the intermediate melanoma group in the current study was 19.3%. However, Morton et al. found 16.0% tumour-positive sentinel nodes in intermediate melanomas [43]. Our literature review showed that SLNB in intermediate melanoma is less controversial, because the staging of intermediate-thickness primary melanomas according to the results of sentinel node biopsy provides important prognostic information and identifies patients with nodal metastases whose survival can be prolonged by immediate lymphadenectomy. Therefore, SLNB is recommended for patients with intermediate-thickness melanomas of any anatomic site [43]. Locoregional recurrence, distant metastases and death attributed to melanoma were detected in 26.3%, 29.5% and 20%, respectively, of patients with intermediate melanomas and positive SLNB, and were significantly different from the patients with negative SLNB. (p<0.001). In contrast, Morton et al. reported a 26.2% melanoma-specific mortality rate in the biopsy group if the node contained metastases [43], which might be due to the thicker mean Breslow’s depth in their groups compared with our patients (1.98 ± 0.63 mm vs 1.92 ± 2.70 mm). A significant difference between sentinel node negative and node positive groups was also observed in our study for disease-free and overall survival (p <0.001). This observation is consistent with prior reports of intermediate melanoma patients by Morton et al., which showed significantly shorter disease-free and overall survival in their patients with intermediate melanomas if the sentinel node was free of metastases (p <0.001) [43].

Positive SLNB was observed in 38.8% of the patients with thick melanoma in the current study. Despite the fact that SLNB for lymph node staging of thick primary cutaneous melanomas has been recommended by various guideline and studies [17, 29, 44–48], its beneficial effects are still controversial [11, 26, 44]. Opponents state that the procedure is useless in the patients with thick melanoma because it does not provide significant prognostic information, and outcome will be changed by occult metastasis and not SLNB status [10, 26, 44, 49, 50]. These statements have been supported by studies showing no benefit in overall survival according to the SLNB result [10, 11, 51]. On the other hand, other evidence indicates that patients with thick melanoma are not a homogenous group regarding prognosis and tumour behaviour. Those with regional node involvement may belong to a subgroup of thick melanoma patients with a significantly worse prognosis than those with negative SLNB [10, 26, 29, 52]. Evaluation of patients with thick melanomas in the current study showed 51.1% locoregional recurrence, 46.8% distant metastases and 34% death attributed to melanoma, which were significantly more frequent in the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.001, p = 0.017 and p = 0.05, respectively). Likewise, Fairbairn et al. found a 50% disease recurrence rate in patients with positive SLNB compared with 23% in those with negative results [10]. Jacobs et al. found 8% disease recurrence in the patients with a negative SLNB and 40% recurrence in the SLNB positive group [29]. Furthermore, survival analysis showed significantly better disease-free survival in the patients with negative SLNB than in the patients with positive SLNB (p = 0.008). Our findings provide support for the previous analyses by Rughani et al. [53], Gajdos et al. [26], Fujisawa et al. [12], Mozzillo [40] and Fairbairn et al. [10], which showed that SLNB negative thick melanomas were associated with a significantly better disease-free survival. However, despite worse mean overall survival of the patients with positive SLNB than of the patients with negative SLNB, this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.13). In a similar study, Fairbairn et al. [10] did not find a significant difference in overall survival between the SLNB positive and negative groups (p = 0.66). On the other hand, Gershenwald et al. [27], Gajdos et al. [26], Ferrone et al. [54], Carlson et al. [52], Rughani et al. [53], Fujisawa et al. [12] and Mozzillo et al. [40] reported that overall survival differed significantly for the SLNB positive patients compared with the SLNB negative group.

Our current study is certainly not without limitations. The chief of them was the study design – a retrospective observational study – and all the biases associated with this kind of study should be taken into consideration. Furthermore, we were not able to assess concerns about the morbidities and complication rates following SLNB for our melanoma patients.

The information obtained from the present study provides insight into application of SLNB as a prognostic indicator in patients with different thicknesses of melanoma. Based on a recent phase III trial conducted by Morton et al. [38], performing SLNB per se might not significantly change 10-year melanoma-specific survival, but it can significantly prolong 10-year disease-free survival compared with an observation group. Furthermore, biopsy-based staging of melanomas provides important prognostic information, and its outcome will inform the next steps in patient management, as it identifies patients with nodal metastases who might benefit from immediate complete lymphadenectomy or use of potential adjuvant therapies [38, 42, 55, 56].

1 Garbe C, Peris K, Hauschild A, Saiag P, Middleton M, Spatz A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of melanoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline – Update 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2012;48(15):2375–90.

2 Sladden MJ, Balch C, Barzilai DA, Berg D, Freiman A, Handiside T, et al. Surgical excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;4.

3 Heppt MV, Reinholz M, Tietze JK, Kerl K, French LE, Berking C, et al. Clinicopathologic features of primary cutaneous melanoma: a single centre analysis of a Swiss regional population. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25(2):127–32.

4 Bennàssar A, Ishioka P, Vilalta A. Surgical treatment of primary melanoma. Dermatol Ther. 2012;25(5):432–42.

5 Lens M, Dawes M. Global perspectives of contemporary epidemiological trends of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Br J Dermatol. 2004;150(2):179–85.

6 Bouchardy C, Lutz J-M, Kühni C. Cancer in Switzerland, Situation and development from 1983 to 2007. 2011.

7 Morton DL, Cochran AJ, Thompson JF, Elashoff R, Essner R, Glass EC, et al. Sentinel node biopsy for early-stage melanoma: accuracy and morbidity in MSLT-I, an international multicenter trial. Ann Surg. 2005;242(3):302–11.

8 Valsecchi ME, Silbermins D, de Rosa N, Wong SL, Lyman GH. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with melanoma: a meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(11):1479–87.

9 Balch CM, Soong SJ, Gershenwald JE, Thompson JF, Reintgen DS, Cascinelli N, et al. Prognostic factors analysis of 17,600 melanoma patients: validation of the American Joint Committee on Cancer melanoma staging system. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(16):3622–34.

10 Fairbairn NG, Orfaniotis G, Butterworth M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in thick malignant melanoma: a 10-year single unit experience. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2012;65(10):1396–402.

11 Hunger RE, Michel A, Seyed Jafari SM, Shafighi M. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in thick malignant melanoma: A 16-year single unit experience. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25(5):472–6.

12 Fujisawa Y, Otsuka F, Japanese Melanoma Study G. The benefit of a sentinel lymph node biopsy and adjuvant therapy in thick (>4 mm) melanoma: multicenter, retrospective study of 291 Japanese patients. Melanoma Res. 2012;22(5):362–7.

13 Coit DG, Andtbacka R, Anker CJ, Bichakjian CK, Carson WE 3rd, Daud A, et al. Melanoma. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2012;10(3):366–400.

14 Squires MH, 3rd, Delman KA. Current treatment of locoregional recurrence of melanoma. Curr Oncol Rep. 2013;15(5):465–72.

15 Grotz TE, Glorioso JM, Pockaj BA, Harmsen WS, Jakub JW. Preservation of the deep muscular fascia and locoregional control in melanoma. Surgery. 2013;153(4):535–41.

16 Karakousis CP, Balch CM, Urist MM, Ross MM, Smith TJ, Bartolucci AA. Local recurrence in malignant melanoma: long-term results of the multiinstitutional randomized surgical trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 1996;3(5):446–52.

17 Balch CM, Gershenwald JE, Soong SJ, Thompson JF, Atkins MB, Byrd DR, et al. Final version of 2009 AJCC melanoma staging and classification. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(36):6199–206.

18 Hunger RE, Seyed Jafari SM, Angermeier S, Shafighi M. Excision of fascia in melanoma thicker than 2 mm: no evidence for improved clinical outcome. Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1391–6.

19 Hunger RE, Angermeier S, Seyed Jafari SM, Ochsenbein A, Shafighi M. A retrospective study of 1- versus 2-cm excision margins for cutaneous malignant melanomas thicker than 2 mm. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72(6):1054–9.

20 Gillgren P, Drzewiecki KT, Niin M, Gullestad HP, Hellborg H, Månsson-Brahme E, et al. 2-cm versus 4-cm surgical excision margins for primary cutaneous melanoma thicker than 2 mm: a randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;378(98.03):1635–42.

21 Hudson LE, Maithel SK, Carlson GW, Rizzo M, Murray DR, Hestley AC, et al. 1 or 2 cm margins of excision for T2 melanomas: do they impact recurrence or survival? Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(1):346–51.

22 Kyrgidis A, Tzellos T, Mocellin S, Apalla Z, Lallas A, Pilati P, et al. Sentinel lymph node biopsy followed by lymph node dissection for localised primary cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;5:Cd010307.

23 Ross MI. Sentinel node biopsy for melanoma: an update after two decades of experience. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2010;29(4):238–48.

24 Morton DL. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy for melanoma: past, present, and future. Ann Surg Oncol. 2001;8(9 Suppl):22S–28S.

25 Ranieri JM, Wagner JD, Wenck S, Johnson CS, Coleman JJ 3rd. The prognostic importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(7):927–32.

26 Gajdos C, Griffith KA, Wong SL, Johnson TM, Chang AE, Cimmino VM, et al. Is there a benefit to sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with T4 melanoma? Cancer. 2009;115(24):5752–60.

27 Gershenwald JE, Mansfield PF, Lee JE, Ross MI. Role for lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thick (> or = 4 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(2):160–5.

28 Scoggins CR, Bowen AL, Martin RC 2nd, Edwards MJ, Reintgen DS, Ross MI, et al. Prognostic information from sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thick melanoma. Arch Surg. 2010;145(7):622–7.

29 Jacobs IA, Chang CK, Salti GI. Role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thick (>4 mm) primary melanoma. Am Surg. 2004;70(1):59–62.

30 Corsetti RL, Allen HM, Wanebo HJ. Thin < or = 1 mm level III and IV melanomas are higher risk lesions for regional failure and warrant sentinel lymph node biopsy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(6):456–60.

31 Bedrosian I, Faries MB, Guerry D 4th, Elenitsas R, Schuchter L, Mick R, et al. Incidence of sentinel node metastasis in patients with thin primary melanoma (< or = 1 mm) with vertical growth phase. Ann Surg Oncol. 2000;7(4):262–7.

32 Lowe JB, Hurst E, Moley JF, Cornelius LA. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2003;139(5):617–21.

33 Jacobs IA, Chang CK, DasGupta TK, Salti GI. Role of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin (<1 mm) primary melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(5):558–61.

34 Nahabedian MY, Tufaro AP, Manson PN. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for the T1 (thin) melanoma: is it necessary? Ann Plast Surg. 2003;50(6):601–6.

35 Warycha MA, Zakrzewski J, Ni Q, Shapiro RL, Berman RS, Pavlick AC, et al. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node positivity in thin melanoma (<or = 1 mm). Cancer. 2009;115(4):869–9.

36 Joyce KM, McInerney NM, Joyce CW, Jones DM, Hussey AJ, Donnellan P, et al. A review of sentinel lymph node biopsy for thin melanoma. Ir J Med Sci. 2015;184(1):119–23.

37 Green AC, Baade P, Coory M, Aitken JF, Smithers M. Population-based 20-year survival among people diagnosed with thin melanomas in Queensland, Australia. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(13):1462–7.

38 Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Nieweg OE, Roses DF, et al. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(7):599–609.

39 Wright BE, Scheri RP, Ye X, Faries MB, Turner RR, Essner R, et al. Importance of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Arch Surg. 2008;143(9):892–9.

40 Mozzillo N, Pennacchioli E, Gandini S, Caracò C, Crispo A, Botti G, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in thin and thick melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(8):2780–6.

41 Wong SL, Brady MS, Busam KJ, Coit DG. Results of sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thin melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13(3):302–9.

42 Phan GQ, Messina JL, Sondak VK, Zager JS. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for melanoma: indications and rationale. Cancer Control. 2009;16(3):234–9.

43 Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, Mozzillo N, Elashoff R, Essner R, et al. Sentinel-node biopsy or nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(13):1307–17.

44 Martinez SR, Shah DR, Yang AD, Canter RJ, Maverakis E. Sentinel lymph node biopsy in patients with thick primary cutaneous melanoma: patterns of use and underuse utilizing a population-based model. ISRN Dermatol. 2013;2013:315609.

45 Gershenwald JE, Ross MI. Sentinel-lymph-node biopsy for cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(18):1738–45.

46 Covarelli P, Vedovati MC, Becattini C, Rondelli F, Tomassini GM, Messina S, et al. The sentinel node biopsy in patients with thick melanoma: outcome analysis from a single-institution database. In vivo. 2011;25(3):439–43.

47 Ra JH, McMasters KM, Spitz FR. Should all melanoma patients undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy? Curr Opin Oncol. 2006;18(2):185–8.

48 Marsden JR, Newton-Bishop JA, Burrows L, Cook M, Corrie PG, Cox NH, et al. Revised UK guidelines for the management of cutaneous melanoma 2010. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2010;63(9):1401–19.

49 Thompson JF, Shaw HM. The prognosis of patients with thick primary melanomas: is regional lymph node status relevant, and does removing positive regional nodes influence outcome? Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(8):719–22.

50 Perrott RE, Glass LF, Reintgen DS, Fenske NA. Reassessing the role of lymphatic mapping and sentinel lymphadenectomy in the management of cutaneous malignant melanoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;49(4):567–88.

51 Gutzmer R, Al Ghazal M, Geerlings H, Kapp A. Sentinel node biopsy in melanoma delays recurrence but does not change melanoma-related survival: a retrospective analysis of 673 patients. Br J Dermatol. 2005;153(6):1137–41.

52 Carlson GW, Murray DR, Hestley A, Staley CA, Lyles RH, Cohen C. Sentinel lymph node mapping for thick (>or=4-mm) melanoma: should we be doing it? Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(4):408–15.

53 Rughani MG, Swan MC, Adams TS, Marshall A, Asher R, Cassell OC, et al. Sentinel node status predicts survival in thick melanomas: the Oxford perspective. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2012;38(10):936–42.

54 Ferrone CR, Panageas KS, Busam K, Brady MS, Coit DG. Multivariate prognostic model for patients with thick cutaneous melanoma: importance of sentinel lymph node status. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9(7):637–45.

55 Merkow J, Paniccia A, Jones E, Jones T, Hodges M, Stovall R, et al. Association of sentinel lymph node diameter with melanoma metastasis. Am J Surg. 2016;S0002-9610(16)30011–3.

56 Mocellin S, Lens MB, Pasquali S, Pilati P, Chiarion Sileni V. Interferon alpha for the adjuvant treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(6):CD008955.

Disclosure statement: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.