Figure

Recruitment of general practitioners.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14201

In many countries, certification of sickness absence is typically performed by general practitioners (GPs). Sickness certification is a complex process involving numerous judgments and assumptions of the patients’ disease, the credibility of their complaints, their capacity to perform the tasks required at their workplace, and prognostic estimates on the patients’ expected return to work [1–4] In Switzerland, most employers request a sickness certificate on the third day of absence from work to validate the patient’s work incapacity. The certificate, usually issued by the GP, legitimises the employee’s absence, gives access to social security, and facilitates his or her return to work [5, 6].

Physicians in other countries, mostly GPs, are known to find sickness certification a problematic task. Three systematic reviews [7–9] indicate several problems that physicians experience: a role conflict between caring for a sick person and judging a claim for sickness absence, relational problems with the patient when the physician feels that the claim is not justified, and a lack of knowledge and skills to assess work capacity and the expected duration of work incapacity. Later studies [10–15] point to the same problems in sickness certification.

Researchers suggest different types of solutions: changing the procedure of sickness certification in healthcare provision [16], adapting the role and influence of the employer [17], but most of all researchers suggest improving the knowledge and skills of the certifying physicians [7, 8]. One limitation of the present knowledge regarding GPs’ sickness certification practices is that the studies are predominantly from the Scandinavian countries and the United Kingdom. One study from Switzerland from 2007 [16] suggests that similar problems exist there. These problems were identified in free texts, however, and their frequency cannot be compared with the findings of those from other countries. For this, a survey among GPs in different areas of Switzerland, using set items with questions about frequencies, would be needed.

We were interested to know if the same problems exist in Switzerland and to the same degree as in other countries and what solutions would be directly accessible to GPs (leaving aside changes of the healthcare system and the role of employers). Switzerland is especially interesting as it consists of three regions that differ in language. The legal conditions with regard to healthcare and sickness absence do not differ between the Swiss regions.

The aim of this study was to explore the views of Swiss GPs about sickness certification, their practices and experience, with a focus on professional skills and on problematic interactions with patients.

We conducted a cross-sectional study with a web-based questionnaire survey among Swiss GPs on their experience and attitudes towards sickness certification.

We disseminated the questionnaire through existing networks of GPs affiliated with the five academic institutes for primary care (Basel, Berne and Zurich in German-speaking Switzerland, 65% of the population; Geneva and Lausanne in French-speaking Switzerland, 23% of the population). These institutes organise training in primary care during formal education, undertake research, and act as important stakeholders for GPs.

The participants were GPs issuing sickness certificates as part of their clinical practice.

We developed a comprehensive questionnaire. The issues addressed in the survey were identified through the literature, public debate [18, 19], and focus group interviews with GPs associated with the Institute for Primary Care Basel. We drafted, discussed and fine-tuned questions in iterative rounds. We integrated 25 questions including their Likert scales, from a comprehensive Swedish questionnaire on sickness certification practices that had been administered in numerous studies in Sweden and other countries [14, 20–27]. We translated the Swedish questions into German and French, and verified them with bilingual researchers (L.H, J.S) from the institutes for primary care in Lausanne and Geneva. We pretested the questionnaire with physicians who were not involved in the questionnaire development, by asking them to go through the survey and report any misunderstanding of questions or any question that they found inappropriate.

The final questionnaire contained 51 closed questions and 3 open-ended questions to collect data on specific experience and approaches for potential solutions to perceived problems. Here, we report results of 37 closed items related to the study aim. Those items address the following four main categories.

1. Behaviour and experiences of physicians with patients (10 questions) and employers (2 questions) in sickness certification, including potentially adversarial situations (12 questions such as “How often do you face problems with patients around the certification of sickness absence?”) with six response options on frequency.

2. Professional skills required for certifying sickness absences that physicians may experience as problematic (12 questions such as “How problematic do you find it to provide a long-term prognosis about the patient’s future work capacity?”) with response options “very problematic”, “rather problematic”, “somewhat problematic”, “not at all problematic”.

3. Different approaches to advance competence in sickness certification (seven options to consider “What approaches do you regard as suitable to acquire or advance competence in certifying sickness absence?” as “very suited”, “somewhat suited” and “not suited”).

4. Views on sickness certification in the professional context (six descriptions “how would you describe certification of sickness absence?” with the option to agree or disagree on e.g., “it is a negotiation”, “a daily battle”; “prescription of a medical therapy”).

In addition, we elicited sociodemographic information on age, gender, professional training, years worked in primary care, and number of sickness certificates issued per week.

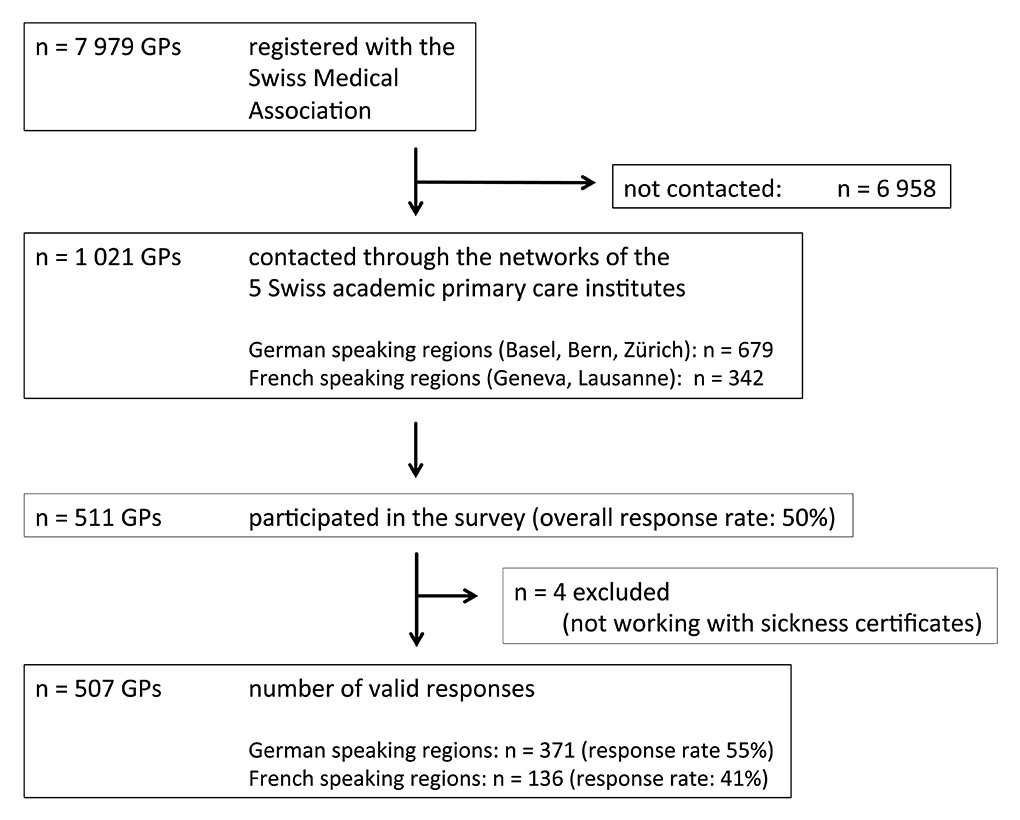

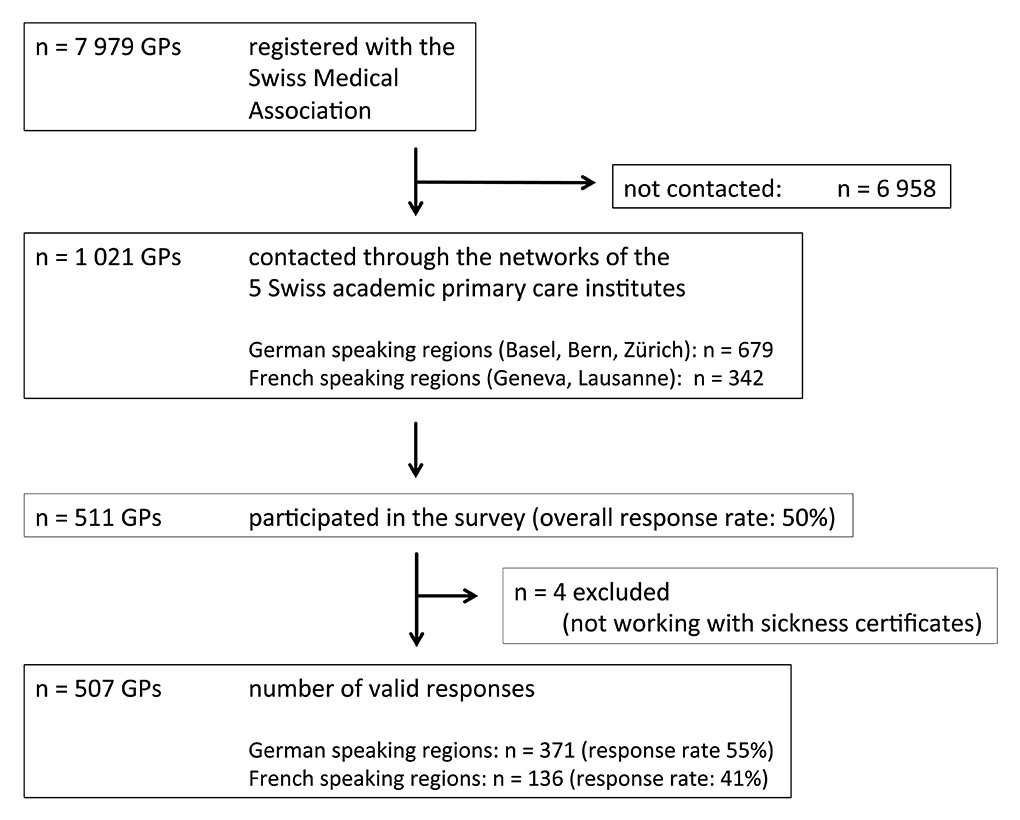

The institutes in Basel, Berne and Zürich conducted the survey between July and December 2013, the institutes in Lausanne and Geneva between May and August 2014, with two reminders each, distributed by the institutes to their associated GPs via e-mail. The invitation letters contained information about the background of the study, its goals, the content of the questionnaire, and time requirements to fill it out. We also mentioned that participation in the study implied informed consent and that there were no incentives for taking part in the survey. The survey was hosted by online survey platform https://www.surveygizmo.com/ . We contacted 1 021 physicians, representing 12% of all registered GPs in Switzerland.

We present our findings in accordance with the guidance proposed by Bennett and colleagues for survey research [28]. We included all eligible questions that provided more than just demographic information, irrespective of the number of questions answered. We used descriptive statistics to analyse the responses. We dichotomised the response options in table 3 (pooling “very problematic” and “rather problematic”) and in table 4 (pooling “very suited” and “somewhat suited”). Because of few missing data, we analysed every item and treated missing values as “missing per item”. We used X2-statistics to compare the results from German- and French-speaking Switzerland, defining a p-level of 0.01 as significant.

The study was approved by the ethics board Basel (EKNZ Ethikkommission Nordwestschweiz) – (reference EK 337/13)

| Table 1:Characteristics of the survey population. | ||||

| All respondents n = 511 | German-speaking n = 372 | French-speaking n = 139 | χ2 test statistics | |

| Gender (female) | 125 (24%) | 78 (21%) | 47 (33%) | p <0.01 |

| Age group: 30–39 years 40–49 years 50–59 years 60–64 years 65+ years | 24 (4%) 119 (24%) 206 (41%) 128 (25%) 31 (6%) | 14 (4%) 84 (23%) 157 (42%) 95 (25%) 22 (6%) | 10 (5%) 35 (26%) 49 (37%) 33 (25%) 9 (7%) | p = 0.75 |

| Time practiced as general physician: Up to 4 years 5–9 years 10 and more | 34 (6%) 64 (13%) 410 (81%) | 22 (6%) 39 (10%) 310 (84%) | 12 (7%) 25 (19%) 100 (74%) | p = 0.64 |

| Discipline: General internal medicine General medicine Other | 256 (51%) 219 (44%) 33 (5%) | 166 (45%) 176 (48%) 28 (7%) | 90 (67%) 43 (32%) 5 (1%) | p <0.01 |

| Certificates per week: None 1 per month 1 to 5 6 to 20 >20 | 4 (1%) 12 (2%) 173 (34%) 269 (53%) 53 (11%) | 1 (0%) 8 (2%) 106 (29%) 215 (58%) 42 (11%) | 3 (2%) 4 (3%) 67 (49%) 54 (40%) 11 (8%) | (without “never”) p <0.01 |

| Excluded GPs issuing no certificates | n = 4 | n = 1 | n = 3 | |

| Valid questionnaires for analysis | n = 507 | n = 371 | n = 136 | |

| Table 2:Situations and activities in sickness certification, encountered at least once a week. | ||||

| All respondents n = 507 | German-speaking n = 371 | French-speaking n = 136 | χ2 test statistics | |

| (a) Global rating of adversarial situations: | ||||

| GP perceive sickness certification as problematic | 158 (31%) | 123 (33%) | 32 (24%) | p = 0.05 |

| (b) General behaviour around sickness certification: | ||||

| GP recommends sick leave and patient declines | 45 (9%) | 33 (9%) | 12 (9%) | p = 0.99 |

| GP contacts employer | 7 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 0 | p = 0.10 |

| Employer contacts GP | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 0 | p = 0.22 |

| GP consults with colleagues | 3 (1%) | 2 (0.5%) | 1 (1%) | p = 0.79 |

| (c) Potentially adversarial situations: | ||||

| GP experience difficulties with patients | 69 (14%) | 49 (13%) | 20 (15%) | p = 0.62 |

| Patient requests sick leave for a nonmedical reason | 53 (10%) | 36 (10%) | 17 (12%) | p = 0.36 |

| Patient requests sick leave and GP declines | 40 (8%) | 31 (8%) | 9 (7%) | p = 0.51 |

| GP issues sickness certificate for a nonmedical reason | 38 (6%) | 15 (4%) | 13 (10%) | p = 0.01* |

| GP issues sickness certificate without face-to-face consultation | 19 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 6 (4%) | p = 0.61 |

| Patient tries to make GP feel guilty | 20 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 7 (5%) | p = 0.43 |

| GP worries that patient would change GP in the event of a refusal | 7 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (2%) | p = 0.33 |

| * Significant p-value (≤0.01) | ||||

| Table 3:Tasks related to sickness certification that general practitioners experience as problematic (pooling the responses for “very problematic” and “rather problematic”). | ||||

| All respondents n = 507 | German-speaking n = 371 | French-speaking n = 136 | χ2 test statistics | |

| (a) global rating: | ||||

| Find it problematic to handle sickness certifications | 43 (9%) | 28 (8%) | 15 (11%) | p = 0.21 |

| (b) ratings of specific tasks: | ||||

| To estimate long-term prognosis about future work capacity | 313 (64%) | 223 (60%) | 90 (74%) | p <0.01* |

| To handle situations where GP and patient disagree about the need for sick leave | 272 (54%) | 170 (46%) | 102 (76%) | p <0.01* |

| To assess the reduction in work capacity with regards to job demands | 214 (42%) | 142 (38%) | 72 (53%) | p <0.01* |

| To assess the optimal duration of sick leave | 144 (29%) | 80 (22%) | 64 (47%) | p <0.01* |

| To assess whether functional capacity is reduced | 136 (27%) | 91 (25%) | 45 (34%) | p <0.05 |

| To talk about lifestyle changes | 75 (15%) | 43 (12%) | 32 (24%) | p <0.01* |

| To prolong a certificate initially issued by another physician | 72 (14%) | 39 (11%) | 33 (24%) | p <0.01* |

| To address psychosocial problems | 60 (12%) | 37 (10%) | 23 (17%) | p <0.05 |

| To determine whether reduced work capacity is due to disease or injury | 49 (10%) | 40 (11%) | 9 (7%) | p = 0.15 |

| To decide which aspects about sickness certification to document in patients’ file | 33 (7%) | 21 (6%) | 12 (9%) | p = 0.17 |

| To discuss advantages and disadvantages of being sickness absent with patients | 31 (6%) | 14 (4%) | 17 (13%) | p <0.01* |

| * Significant p-value (≤0.01) | ||||

Of 1 021 invited GPs, 511 participated in the survey (response rate 50%). Four physicians with no exposure to sickness certification and without answers to certification practice were excluded. Figure 1 shows the recruitment and responses of GPs.

Figure

Recruitment of general practitioners.

Table 1 presents the distribution of gender, age, discipline, time practiced in primary care, and sickness certificates issued per week, for all participants and according to language region. Three-quarters of the respondents were male, 71% older than 50 years. Respondents were trained as general internist (51%) or general care physician (44%), which are the typical qualifications in Switzerland for practicing as a GP. Eighty-one percent had been practicing as a GP for 10 years and more. Almost all issued at least one sickness certificate per week and 10% issued more than 20 per week.

The majority of GPs rejected the notion that handling sickness certification was a problematic task (104/507 (21%) not at all; 359 / 507 (71%) somewhat), only a few agreed strongly or very strongly (43/507 GPs, 8%, Swiss-German n = 28; Swiss-French: n = 15). Nevertheless, 31% (155/507) encountered problematic situations around sickness certification at least once a week.

Table 2 summarises numbers and rates of GPs who experienced certain situations with patients and employers regarding sickness certification at least once a week. Participants reported potentially adversarial situations where patients requested sick leave for nonmedical reasons (11%), where they disagreed with the patients’ expectations (14%), or where patients made a request and GPs declined (8%). Very few GPs worried that patients would leave because they declined the patients’ request for a sickness certificate (1%). In nonadversarial interactions, 9% encountered situations where they recommended sick leave and the patient declined. Consultations with colleagues or contacts with employers occurred hardly ever.

From a list of 12 sickness certification tasks, the following tasks ranked as top problems (table 3): providing long-term prognosis about future work capacity (64%), handling disagreement with the patient on the need for sick leave (54%), assessing the patient’s reduction of work capacity (42%) and functional capacity in general (27%), or recommending optimal duration of sick leave (28%). Discussion about lifestyle, psychosocial issues, advantages and disadvantages of sick leave, genuine tasks of primary care, presented only infrequently as problematic.

The vast majority of GPs opted for six out of seven opportunities as suitable to acquire or improve competence in sickness certification: specific training during residency in the office (93%) or hospital setting (86%), a forum to discuss with colleagues (83%), courses in insurance medicine (81%) and conflict management (80%), and access to a second opinion from a colleague (80%) (table 4).

When offered six different perspectives on how to view certification of sickness absence in the professional context, the majority considered it as a negotiation process between GP and patient (79%), as prescription of treatment (69%), or as a medical service to be delivered as part of the professional duties (64%). Fifty percent felt it was a problematic task, while 25% experienced it as a satisfying aspect of their medical practice. Ten percent saw it as a daily battle (table 5).

In French-speaking Switzerland, a higher proportion of female GPs participated in the survey (35 vs 21%), a higher proportion of physicians issued between one and five certificates (48% vs 29%) and correspondingly, a lower proportion 6–20 certificates (39% vs 58%) (table 1). A higher proportion of French-speaking GPs found the specific skills related to sickness certification as problematic (table 3), whereas all but one of seven options for advancing competences gained endorsement by more than 75% in both language regions (table 4). In both language regions, the majority of respondents viewed sickness certification as a negotiation process, as a therapeutic prescription and a professional duty, with a higher proportion of French-speaking GPs opting for negotiation (89% vs 75%) and therapeutic prescription (86% vs 63%) and a smaller proportion viewing it as a problematic task (44% vs 64%) (table 5).

| Table 4:Preferred approaches to improve competence in sickness certification (pooling the responses for “very suited” and “somewhat suited”). | ||||

| All respondents n = 507 | German-speaking n = 371 | French-speaking n = 136 | χ2 test statistics | |

| Specific training during residency in ambulatory setting | 464 (93%) | 337 (91%) | 127 (96%) | p = 0.06 |

| Specific training during residency in hospital | 439 (86%) | 312 (85%) | 118 (88%) | p = 0.32 |

| Forum to discuss issues with colleagues | 417 (83%) | 293 (80%) | 124 (93%) | p <0.01* |

| Courses in insurance medicine | 409 (81%) | 288 (79%) | 121 (90%) | p <0.01* |

| Courses in conflict management | 402 (80%) | 296 (81%) | 106 (79%) | p = 0.59 |

| Opportunity for a second opinion | 394 (80%) | 291 (80%) | 103 (79%) | p = 0.90 |

| National disease-specific guidelines for sickness certification | 246 (51%) | 171 (54%) | 75 (44%) | p = 0.06 |

| * Significant p-value (≤0.01) | ||||

| Table 5:Views on sickness certification in a professional context. | ||||

| All respondents n = 507 | German-speaking n = 371 | French-speaking n = 136 | χ2 test statistics | |

| Negotiation between physician and patient | 394 (79%) | 275 (75%) | 119 (89%) | p <0.01* |

| Prescription of a therapy | 343 (69%) | 228 (63%) | 115 (86%) | p <0.01* |

| Service that is expected as part of my professional duties. | 316 (64%) | 230 (63%) | 86 (65%) | p = 0.66 |

| Challenging task | 289 (58%) | 232 (64%) | 57 (44%) | p <0.01* |

| Satisfying aspect of medical practice | 137 (28%) | 111 (31%) | 26 (20%) | p = 0.01* |

| Daily battle | 52 (11%) | 38 (11%) | 14 (11%) | p = 0.98 |

| * Significant p-value (≤0.01) | ||||

We surveyed 507 general practitioners in Switzerland (representing 6% of all GPs) regarding their experience of and attitudes towards sickness certification. Few respondents regarded sickness certification as a problematic task as such, yet one-third reported experiencing problematic situations with patients at least once a week. Respondents commonly experienced as problematic tasks of determining a long-term prognosis, handling disagreement with the patients on the need for sick leave, and establishing the patients’ reduced work capacity, and approved a variety of training opportunities for enhancing their competences. Differences between German- and French-speaking regions exist but are not profound.

A high response rate of 50% documents the importance of sickness certification to GPs. We used multiple approaches (literature review, focus groups, feedback from field experts) to develop sensitive questions, starting with a Swedish survey which has been used internationally [23, 27, 29].

We limited the survey to GPs, excluding hospital physicians and office-based specialists who also issue sickness certificates. By distributing the survey through the networks of the five academic institutes of primary care, we addressed physicians with an interest in research who were likely to be critical and interested in quality of care. Compared with all Swiss GPs, our respondents were older and of male sex [30]. Older GPs are likely to have more experience in handling situations in daily practice and may have worked out their own ways to solve them. Selection bias may have led to both over- and underreporting of problems. We did not collect information on nonresponders.

About 14% of our respondents reported that problematic situations with patients occur on a weekly basis. Studies where the same questions have been used reveal similar rates among GPs in in Sweden (14.1%) and in Norway (11.5%) [23]. Swiss GPs rate these situations as less problematic than their Swedish and Norwegian colleagues. This could be related to many factors, such as the self-certification time: employees in Switzerland need a certificate after 2 days, in Sweden this is 7 days and in Norway –depending on the company – 3 or 8 days. Possibly, sickness that persists after 1 week is more serious and poses more problems to GPs. Differences between German- and French-speaking GPs within Switzerland are not explained by these factors; cultural (e.g., the patient-doctor relationship) and economic (e.g., employee protection) differences could also play a role and this would be worth further investigation.

Few studies reported on direct contacts between physician and employer [16], although the employer’s attitude or working conditions influence the physician’s assessment of the patients work capacity. We confirm that contact between physician and employer rarely occurs. It is up to the judgement of GPs to estimate whether or not contact with the employer of a sick-listed patient would be beneficial.

Assessing the degree of reduction in work capacity and for which specific work tasks it is reduced, estimating the optimal duration of sick leave and how long this reduction is going to persist, are genuine activities of issuing a sickness certificate. These are problematic aspects to the GPs in Switzerland, as they are in Sweden and Norway [23], even if the proportions in Switzerland experiencing this are a bit lower.

GPs participating in this study opted for specific training on sickness certification in general residence or during medical education/residency in general practice as main options to improve their competence. A vast majority also viewed courses on insurance medicine and conflict management as appropriate means, indicating a need for more such competence. Our results are in line with literature that suggested additional training in sickness certification to strengthen the role of physicians as certifying physicians [31]. Swiss GPs indicated high approval of a course in conflict management, highlighting the aspect of (sometimes problematic) communication in sickness certification.

This and previous surveys from Switzerland [16, 32] report differences and common features compared with the results from Scandinavia and the UK. In contrast to these countries, Swiss GPs consistently viewed sickness certification as a genuine professional task and some even experienced it as a satisfying aspect of their practice. In principle, they consider themselves in a good position to deliver the service, given their knowledge of the patients’ antecedents.

Nevertheless, they find problems with these tasks similar to those of their Scandinavian and British colleagues, in particular with reference to the core tasks in sickness certification and with the physician-patient relationship. Swiss GPs call for training at all levels of medical education. However, in order to keep up with good practice and a good relationship with their patient, some suggest facilities for delegating patients to an independent expert if the medical case is complex, if the patient needs long-term sick leave, or if the situation threatens the physician-patient relationship.

This survey shows that sickness certification has genuine challenges across social insurance settings but other problems that impact on attitudes, experiences and practices may well be rooted in the particularities of each national system. International comparative research can help to disentangle the two and allow learning between GPs working in different systems.

When compared with GPs from Scandinavian countries and the UK, sickness certification as such does not present a major problem to Swiss general practitioners. Nevertheless, Swiss GPs identified a lack of competence to deal with specific sickness certification tasks. Training opportunities on sickness certification and insurance medicine in general are welcomed.

Acknowledgements:We thank all respondents for providing us with answers to our questions.

Authors' contributions:SK and WdB prepared the study; SK, WdB, KA developed the study design; SK, WdB, AZ, TR, PF, JS, LH, KA, and RK developed the German and French questionnaires; SK, WdB, AZ, TR, PF, JS, LH disseminated the survey; SK collected and analysed the data; SK, WdB, RK drafted the manuscript; all authors critically reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Supplementary materials:Materials related to this paper can be accessed via the corresponding author.

1 Nilsing E, Soderberg E, Oberg B. Sickness certificates in Sweden: did the new guidelines improve their quality? BMC Public Health. 2012;12:907.

2 Soderberg E, Alexanderson K. Sickness certificates as a basis for decisions regarding entitlement to sickness insurance benefits. Scand J Public Health. 2005;33(4):314–20.

3 Werner EL, Cote P, Fullen BM, Hayden JA. Physicians’ determinants for sick-listing LBP patients: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(4):364–71.

4 Dunner S, Decrey H, Burnand B, Pecoud A. Sickness certification in primary care. Sozial- und Praventivmedizin. 2001;46(6):389–95.

5 Scheil-Adlung X, Sandner L. The case for paid sick leave In: World health Report, Background Paper 9. WHO; 2010.

6 Adema W, Ladaique M. How Expensive is the Welfare State?: OECD Publishing; 2009.

7 Wynne-Jones G, Mallen CD, Main CJ, Dunn KM. What do GPs feel about sickness certification? A systematic search and narrative review. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2010;28(2):67–75.

8 Letrilliart L, Barrau A. Difficulties with the sickness certification process in general practice and possible solutions: a systematic review. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18(4):219–28.

9 Perk J, Alexanderson K. Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU). Chapter 8. Sick leave due to coronary artery disease or stroke. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2004;63:181–206.

10 Kiessling A, Arrelov B. Sickness certification as a complex professional and collaborative activity – a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:702.

11 Lindholm C, Arrelov B, Nilsson G, Lofgren A, Hinas E, Skaner Y, et al. Sickness-certification practice in different clinical settings; a survey of all physicians in a country. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:752.

12 Foley M, Thorley K, Denny M. “The sick note”: a qualitative study of sickness certification in general practice in Ireland. Eur J Gen Pract. 2012;18(2):92–9.

13 Money A, Hussey L, Thorley K, Turner S, Agius R. Work-related sickness absence negotiations: GPs’ qualitative perspectives. The British journal of general practice: the journal of the Royal College of General Practitioners 2010;60(579):721–8.

14 Engblom M, Nilsson G, Arrelov B, Lofgren A, Skaner Y, Lindholm C, et al. Frequency and severity of problems that general practitioners experience regarding sickness certification. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2011;29(4):227–33.

15 Wainwright E, Wainwright D, Keogh E, Eccleston C. The social negotiation of fitness for work: tensions in doctor-patient relationships over medical certification of chronic pain. Health. 2015;19(1):17–33.

16 Bollag U. Sickness certification in primary care – the physician’s role. Swiss Med Wkly. 2007(137):341–6.

17 Black C. Working for a healthier tomorrow. In: Health, work and wellbeing – evidence and research and Employment Edited by Pensions DfWa. London; TSO; 2008.

18 Tschudi P, Bischoff T. Der Hausarzt und das Arztzeugnis. In: Brennpunkt Arztzeugnis Problemerhebung und Lösungsansätze für Patient, Arzt, Arbeitgebende und Versicherung. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland: asim Swiss Academy for Insurance Medicine 2013.

19 Cohen DA. Sickness Absence Certification: Rolling with Resistance – New Concepts and Models for Change. In: Brennpunkt Arztzeugnis Problemerhebung und Lösungsansätze für Patient, Arzt, Arbeitgebende und Versicherung. Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland: asim Swiss Academy for Insurance Medicine 2013.

20 Branstrom R, Arrelov B, Gustavsson C, Kjeldgard L, Ljungquist T, Nilsson GH, et al. Reasons for and factors associated with issuing sickness certificates for longer periods than necessary: results from a nationwide survey of physicians. BMC Public Health. 2013, 13.

21 Lindholm C, von Knorring M, Arrelöv B, Nilsson G, Hinas E, Alexanderson K. Health care management of sickness certification tasks: results from two surveys to physicians. BMC Res Notes. 2013, 6.

22 Ljungquist T, Hinas E, Arrelöv B, Lindholm C, Wilteus AL, Nilsson GH, et al. Sickness certification of patients – a work environment problem among physicians? Occup Med (Lond). 2013;63(1):23–9.

23 Winde LD, Alexanderson K, Carlsen B, Kjeldgard L, Wilteus AL, Gjesdal S. General practitioners’ experiences with sickness certification: a comparison of survey data from Sweden and Norway. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;13:10.

24 Skånér Y, Nilsson GH, Arrelöv B, Lindholm C, Hinas E, Wilteus AL, et al. Use and usefulness of guidelines for sickness certification: results from a national survey of all general practitioners in Sweden. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2).

25 Löfgren A, Hagberg J, Alexanderson K. What physicians want to learn about sickness certification: analyses of questionnaire data from 4019 physicians. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10(61).

26 Lindholm C, Arrelöv B, Nilsson G, Löfgren A, Hinas E, Skånér Y, et al. Sickness-certification practice in different clinical settings; a survey of all physicians in a country. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1).

27 Ljungquist T, Hinas E, Nilsson G, Gustavsson C, Arrelöv B, K. A. Problems with sickness certification tasks: experiences from physicians in different clinical settings. A cross-sectional nation-wide study in Sweden. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015, Accepted

28 Bennett C, Khangura S, Brehaut JC, Graham ID, Moher D, Potter BK, et al. Reporting guidelines for survey research: an analysis of published guidance and reporting practices. PLoS medicine. 2010;8(8):e1001069.

29 Lindholm C, Arrelov B, Nilsson G, Lofgren A, Hinas E, Skaner Y, et al. Sickness-certification practice in different clinical settings; a survey of all physicians in a country. BMC Public Health. 2010;10(1).

30 FMH: Altersstruktur der berufstätigen Ärzte. In., vol. 2 «Allgemeine Innere Medizin, Allgemeinmedizin, Innere Medizin», ambulanter Sektor, 2015.

31 Werner EL, Côté P, Fullen BM, Hayden JA. Physicians’ determinants for sick-listing LBP patients: a systematic review. Clin J Pain. 2012;28(4):364–71.

32 Dunner S, Decrey H, Burnand B, Pecoud A. Sickness certification in primary care. Soz Praventivmed. 2001;46(6):389–95.

Disclosure statement: No funds were received for the study or the preparation of this manuscript. asim, the Department of Insurance Medicine at the University Hospital in Basel, is funded in part by donations from public insurers and a consortium of private insurance companies. KA was funded by the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare. The present study was asim’s initiative. Insurers were not involved in any phase of the study.