“Swiss physicians’ attitudes to assisted suicide”

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14142

Susanne

Brauer, Christian

Bolliger, Jean-Daniel

Strub

Summary

PRINCIPLES: In Switzerland, assisted suicide is legal as long as it does not involve self-serving motives. Physician-assisted suicide is regulated by specific guidelines issued by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS). This article summarises the results of an empirical study of physicians’ attitudes to assisted suicide in Switzerland, which was commissioned by the SAMS. The study (in German) is available online at: http://www.samw.ch .

METHODS: Twelve qualitative interviews and a written survey were conducted, involving a disproportional, stratified random sample of Swiss physicians (4,837 contacted, 1,318 respondents, response rate 27%).

RESULTS: Due to the response rate and the wide variation of respondents from one professional speciality to another, the findings and interpretations presented should be regarded as applying only to the group of physicians who are interested in or are particularly affected by the issue of assisted suicide. They cannot be generalised to the whole body of physicians in Switzerland. Of the respondents, 77% considered physician-assisted suicide to be justifiable in principle, while 22% were fundamentally opposed to it. Although 43% could imagine situations where they would personally be prepared to perform assisted suicide, it is clear from the study that this potential readiness does not mean that all respondents would automatically be prepared to perform it in practice as soon as the legal criteria are met. The vast majority of respondents emphasised that there should be no obligation to perform physician-assisted suicide. Opinions differed as to whether physician-assisted suicide should remain restricted to cases where the person concerned is approaching the end of life. While a large majority of respondents considered physician-assisted suicide also to be justifiable in principle in non-end-of-life situations, 74% supported the maintenance of the end-of-life criterion in the SAMS Guidelines as a necessary condition for physician-assisted suicide. Over 50% of the respondents had never been confronted with a request for assisted suicide by a patient.

CONCLUSIONS: The vast majority of physicians surveyed considered assisted suicide to be justifiable in principle; however, their support was strongly dependent on the specific situation. The study indicates that even physicians expressing a potential readiness to perform assisted suicide themselves would not do so automatically if all the criteria for assisted suicide were met. Assisted suicide thus appears to be an exceptional situation, which physicians would only become involved in on a voluntary basis. The authors recommend that the current SAMS Guidelines regulating physician-assisted suicide in Switzerland should be reviewed with regard to the end-of-life criterion as a necessary condition for physician-assisted suicide.

A qualitative and quantitative empirical study

Introduction

This study was commissioned by the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences (SAMS) in spring 2013. The aim was to obtain an overview of the range of views held by physicians in Switzerland on the subject of assisted suicide, and of their experiences in this area. The study was prompted by the controversy which arose in 2012 over the regulation of physician-assisted suicide [1]. The SAMS Guidelines on “End-of-life care”, which form part of the Code of the Swiss Medical Association (FMH), allow for the possibility of physician-assisted suicide in exceptional cases, although the criteria specified are more stringent than the general legal requirements for assisted suicide in Switzerland: “Based on the patient’s condition, it can be assumed that the end of life is imminent. Alternative options for providing relief have been discussed and, if desired, implemented. The patient has decisional capacity, and the desire for suicide is well-considered, arose without external pressure, and is persistent. This has been verified by an independent third party, who need not be a physician.” [2] The position paper issued by the Central Ethics Committee of the SAMS in 2012 adds: “In particular, it must be excluded that the desire for suicide is a symptom of a mental disorder.” [3]

Physician-assisted suicide is primarily understood as the prescription or dispensing of a drug for the purpose of suicide [4–6]. Other actions constituting assisted suicide are, for example, inserting or leaving a cannula in place for the purpose of suicide by infusion, or providing specific instructions for suicide [7, 8].

According to the Federal Statistical Office, for persons resident in Switzerland, the number of assisted suicides rose from 187 to 508 between 2003 and 2012; the number of cases of assisted suicide involving persons not resident in Switzerland is not known. Given the lack of precise data available, it is difficult to estimate future developments.

The present study involved a qualitative and a quantitative component. The findings and interpretations relate to the group of physicians who are interested in or particularly affected by the issue of assisted suicide in Switzerland.

|

Table 1: Total of physicians in Switzerland, contacted physicians, and respondents of the questionnaire. |

|

|

Total of physicians

|

Contacted physicians

|

Respondents

|

|

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

n

|

%

|

Response rate (%)

|

|

Total*

|

31,555 |

100 |

4,837 |

100 |

1,318 |

100 |

27 |

|

Language region*

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| German-speaking |

22,066 |

70 |

2,771 |

57 |

766 |

58 |

28 |

| French-speaking |

8,171 |

26 |

1,376 |

28 |

377 |

29 |

27 |

| Italian-speaking |

1,318 |

4 |

690 |

14 |

175 |

13 |

25 |

| |

|

Sex**

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Male |

20,426 |

61 |

3,171 |

66 |

831 |

63 |

26 |

| Female |

12,816 |

39 |

1,666 |

34 |

487 |

37 |

29 |

| |

|

Specialty**

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Family medicine |

6,569 |

20 |

866 |

18 |

312 |

24 |

36 |

| Geriatrics |

195 |

1 |

195 |

4 |

81 |

6 |

42 |

| Psychiatry |

3,426 |

10 |

760 |

16 |

236 |

18 |

31 |

| Medical oncology |

282 |

1 |

282 |

6 |

81 |

6 |

29 |

| Neurology |

503 |

2 |

503 |

10 |

119 |

9 |

24 |

| Other |

22,267 |

67 |

2,231 |

46 |

489 |

37 |

22 |

| Source (population): *FMH membership dataset, February 2014 (basis for random sampling); **FMH Medical Statistics 2013.

Source (contacted physicians/respondents): Survey of physicians conducted by Büro Vatter/Brauer & Strub. |

Methods

Qualitative study (interviews)

Sampling and data collection

Twelve individual structured interviews were conducted with physicians. To ensure balance, the interviewees were selected in accordance with the following criteria: the broadest possible range of views, specialties which are presumably more frequently confronted with groups of patients requesting suicide or with completed suicide, and various regions (German-/French-/Italian-speaking Switzerland), areas (rural/urban) and work settings (hospital/independent practice).

Analysis

The interview data were evaluated using a two-part inductive analysis. The individual case-based analysis examined the positions taken by the subject, the types of supporting argument used, the topics considered important, the concepts employed and the individual perspective. In the thematic cross-analysis, the interviews were compared along thematic dimensions. The resulting thematic structure was used firstly to describe the range of views held and secondly to relate the positions adapted to core ethical values underlying the views expressed.

The goals of the qualitative part of the study were to identify key questions and points associated with the issue of assisted suicide, to document the positions and reasons cited, and to prepare for the quantitative part of the study.

Quantitative study (written survey)

Sampling and data collection

For the written survey, address data were obtained from the membership database of the Swiss Medical Association (FMH) in February 2014. A disproportionate stratified random sample (4837) was then selected, with oversampling of (1) linguistic minorities (Italian- and French-speaking Swiss) and (2) specialties of particular interest – family medicine, psychiatry and psychotherapy (hereafter psychiatry), neurology, medical oncology and geriatrics [9, 10].

After pretesting, where participants were invited to comment on problems, the German questionnaire was translated into Italian and French, and each of the translated versions was checked by two persons with native-speaker expertise in the relevant national language. Attached to the questionnaire was a definition of the term “physician-assisted suicide” and a summary of the applicable regulations. The survey was conducted by post between 7th March and 28th April 2014. The response rate was 27% (n = 1,318). Although only slight differences in readiness to participate were observed between sexes and between language regions, response rates varied widely from one specialty to another (table 1).

Measures

The questionnaire included questions on topics such as the following:

‒ Basic attitude to physician-assisted suicide (“Physicians should not perform assisted suicide”, “Physicians should be allowed to perform assisted suicide”, “Physicians should be obliged to perform assisted suicide”).

‒ Could the respondents imagine any situations where they would personally be prepared to perform assisted suicide? (Possible answers: yes, probably, probably not, no.)

‒ Basic attitude to physician-assisted suicide in particular clinical situations: Do the respondents consider assisted suicide to be justifiable in principle in various scenarios? (Possible answers: yes, probably, probably not, no.)

‒ Attitude to the end-of-life criterion specified in the SAMS Guidelines: Do the respondents believe assisted suicide should only be permissible if the patient can be assumed to be approaching the end of life, i.e. if death can be expected to occur within a matter of days or weeks? (Possible answers: yes, probably, probably not, no.)

‒ Attitude to the provisions specified in the SAMS Guidelines which require a second opinion to be obtained in advance – not necessarily from a physician – on the patient’s decisional capacity and on whether the desire for suicide is well-considered.

Analysis

For the analysis, the results were weighted so as to reflect the actual weight of the various language regions. In the case of specialties, the target weight was not the actual proportion of the total medical population accounted for by the various specialties, but the proportion adjusted to reflect the widely varying response rates. Owing to the response rate and the wide variation of respondents from one professional speciality to another, the findings and interpretations presented here should be regarded as applying to the group of physicians who are interested in or particularly affected by the issue of assisted suicide. Thus the findings cannot be generalised to the whole body of physicians in Switzerland. The weighted results are reported below. They do not differ substantially from the results of an unweighted analysis.

|

Table 2: Respondents’ readiness to perform assisted suicide. |

| Basic attitude to

assisted suicide |

Survey question: Can you imagine any situations where you would be prepared to perform assisted suicide? |

| |

Yes |

Probably |

Probably not |

No |

Don’t know, no answer |

Total |

| Physicians should not perform assisted suicide |

n. |

|

1 |

36 |

246 |

7 |

290 |

| % |

|

|

3 |

19 |

1 |

22 |

| Physicians should be allowed to perform assisted suicide |

n |

252 |

276 |

203 |

161 |

63 |

956 |

| % |

19 |

21 |

15 |

12 |

5 |

73 |

| Physicians should be obliged to perform assisted suicide |

n |

26 |

16 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

49 |

| % |

2 |

1 |

|

|

|

4 |

| No answer

|

n |

3 |

5 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

23 |

| % |

|

|

|

|

|

2 |

| Total

|

n |

281 |

298 |

249 |

414 |

75 |

1,318 |

| % |

21 |

23 |

19 |

31 |

6 |

100 |

| Types of basic attitude |

| Potentially prepared to perform assisted suicide |

n |

570 |

| % |

43 |

| Accepts principle of assisted suicide |

n |

370 |

| % |

28 |

| Opposed to assisted suicide |

n |

290 |

| % |

22 |

| Other |

n |

95 |

| % |

7 |

| Source: Survey of physicians conducted by Büro Vatter/Brauer & Strub; n = 1,318; the figures presented are weighted and rounded. Therefore, their sum may slightly differ from the total numbers. |

|

Table 3: Respondents’ assessment of whether physician-assisted suicide is justifiable in principle for various conditions. |

| |

Survey question: Is physician-assisted suicide justifiable in principle (assuming the patient has decisional capacity)? |

| Patient characteristics |

Yes |

Probably |

Probably not |

No |

Don’t know, no answer |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| Seriously ill, severe pain, end of life |

765 |

58 |

269 |

20 |

81 |

6 |

180 |

14 |

23 |

2 |

| Seriously ill, severe pain, end of life; minors |

338 |

26 |

459 |

35 |

135 |

10 |

299 |

23 |

87 |

7 |

| Serious muscular or neurological disease (e.g. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) |

377 |

29 |

425 |

32 |

199 |

15 |

278 |

21 |

39 |

3 |

| Severe pain due to chronic progressive disease |

306 |

23 |

471 |

36 |

247 |

19 |

238 |

18 |

56 |

4 |

| Advanced age, multimorbidity; dependent on care |

282 |

21 |

360 |

27 |

241 |

18 |

396 |

30 |

39 |

3 |

| Dementia |

125 |

10 |

247 |

19 |

320 |

24 |

542 |

41 |

84 |

6 |

| Refractory, chronic, severe mental illness |

129 |

10 |

290 |

22 |

333 |

25 |

489 |

37 |

77 |

6 |

| Advanced age, healthy; suicide desired for personal reasons |

100 |

8 |

161 |

12 |

265 |

20 |

737 |

56 |

55 |

4 |

| Source: Survey of physicians conducted by Büro Vatter/Brauer & Strub; n = 1,318; the figures presented are weighted and rounded. Therefore, their sum may slightly differ from the total numbers. |

|

Table 4: Respondents’ position on the end-of-life-criterion in the SAMS Guidelines. |

| |

Survey question: Should the following condition be maintained in the SAMS Guidelines? |

| |

Yes |

Probably |

Probably not |

No |

No answer |

| n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

| End of life is imminent |

661 |

50 |

321 |

24 |

112 |

8 |

145 |

11 |

80 |

6 |

| Source: Survey of physicians conducted by Büro Vatter/Brauer & Strub; n = 1,318; the figures presented are weighted and rounded. Therefore, their sum may slightly differ from the total number. |

Results

Selected results of the empirical study are given below. They concern:

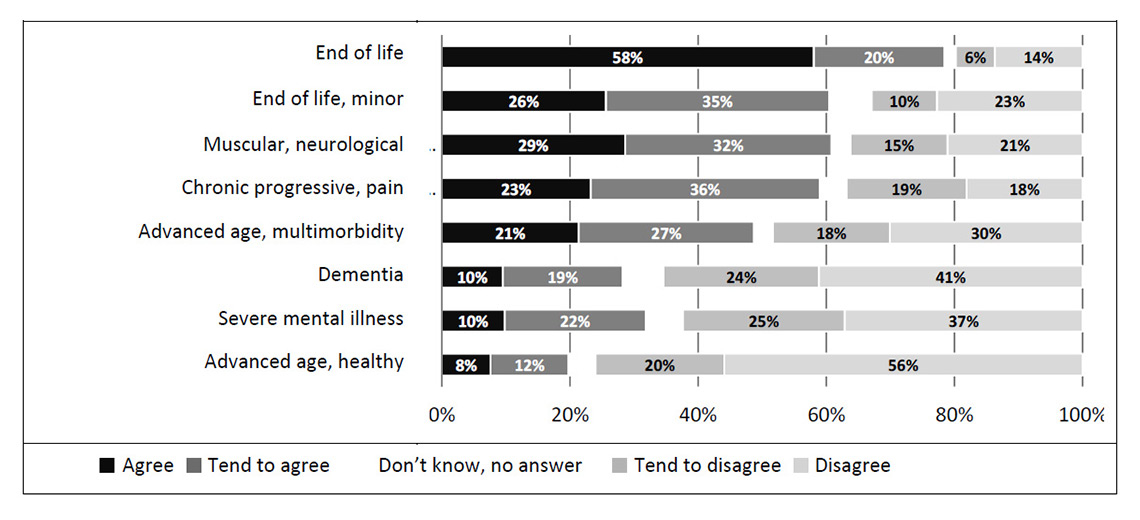

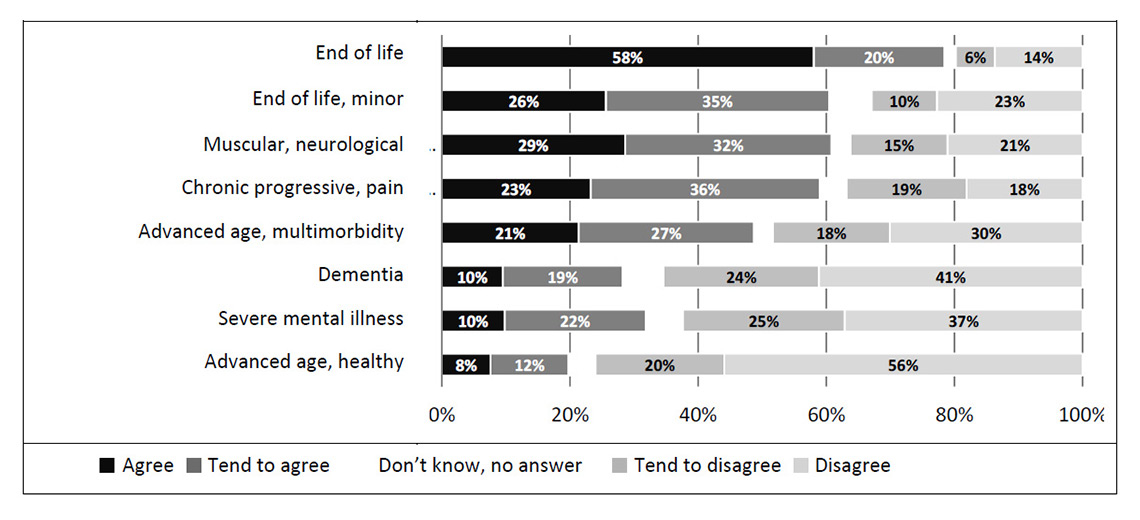

Figure 1

Respondents’ assessment of whether physician-assisted suicide is justifiable in principle for various conditions.

Source: Survey of physicians conducted by Büro Vatter/Brauer & Strub; n = 1,318 (weighted).

Survey question: Is physician-assisted suicide justifiable in principle in the following situations (assuming the patient has decisional capacity)?

‒ Physicians’ basic attitudes to assisted suicide

‒ Attitudes to assisted suicide in relation to specific patient groups

‒ Ethical arguments used to justify or oppose physician-assisted suicide

‒ Physicians’ potential readiness to be involved in a suicide

‒ The end-of-life criterion as a necessary condition for physician-assisted suicide

Physicians’ basic attitudes to assisted suicide

As regards the basic attitude to physician-assisted suicide, the following picture emerges (table 2): 73% of all respondents believed that, in principle, physicians should be allowed to assist suicide if the legal eligibility criteria are met; 22% were fundamentally opposed to assisted suicide; and 4% said that physicians should be obliged to perform assisted suicide if the legal eligibility criteria are met. In conjunction with individual readiness to perform assisted suicide, three basic attitudes to physician-assisted suicide can be identified: while 43% not only considered physician-assisted suicide to be acceptable in principle but could also imagine situations where they would personally be prepared to perform it, 28% tolerate physician-assisted suicide but would not perform it themselves. In contrast to these two groups, 21% are fundamentally opposed to physician-assisted suicide and cannot imagine situations where they would personally be prepared to perform it. Over 50% of the respondents had never been confronted with a request for assisted suicide by a patient.

Attitudes to assisted suicide in relation to specific patient groups

With regard to specific patient groups, the picture is more complex, as is apparent from fig. 1 and table 3.

Physicians were presented with eight different scenarios outlining the condition of various types of person desiring suicide. The question to be answered was: “Regardless of whether you would personally perform assisted suicide, do you consider it justifiable in principle for a physician, on request, to prescribe or dispense a drug to a patient for the purpose of suicide in the following situations? Assume in each case that the person has decisional capacity.”

For patients whose condition meets the eligibility criteria for assisted suicide specified in the SAMS Guidelines – namely, “The person desiring suicide is seriously ill, suffering severe pain and approaching the end of life, i.e. death can be expected to occur within a matter of days or weeks” – a total of 78% considered assisted suicide to be justifiable in principle, answering either “yes” (58%) or “probably” (20%).

In the case of end-of-life patients who are minors, the level of support was lower, totalling 61%. In all the other cases where it is clear from the description that the patient is not at the end of life, the proportion of respondents considering assisted suicide justifiable was also markedly and significantly (p <0.01) lower than for the first situation described:

‒ For patients with a serious muscular or neurological disease (e.g. amyotrophic lateral sclerosis) and for those with severe pain due to chronic progressive disease, around 60% (tended to) support assisted suicide.

‒ For patients of advanced age who have multimorbidity and are dependent on care, supporters and opponents of assisted suicide were roughly equally balanced.

‒ Around 30% (tended to) support assisted suicide in the case of patients with dementia or for persons with severe mental illness.

‒ Around 20% (tended to) support assisted suicide for persons who are of advanced age but otherwise healthy.

A subanalysis revealed neither that psychiatrists showed any over- or underaveraged level of acceptance of assisted suicide for patients with severe pschyciatric disorder, nor that neurologists showed any over- or underaveraged level of acceptance of assisted suicide for patients with severe muscular or neurological disease (see full report p. 73ff.).

It is notable that the level of acceptance of assisted suicide was higher for elderly patients with multimorbidity (48%) than for patients with mental illness (32%) or dementia (29%). With regard to the debate on so-called rational suicide (Bilanzsuizid) in healthy elderly persons, it should also be noted that as many as 20% of the sample surveyed here would consider physician-assisted suicide acceptable. This finding could be related to the observation from the qualitative study that support for physician-assisted suicide is determined not so much by a purely medical view of the severity of disease as by the subjective suffering of the person concerned and the impossibility of mobilising further medical, personal or social resources to alleviate this suffering.

Overall, for the majority of respondents, support for assisted suicide depends on the specific situation. This was in line with the findings of the qualitative interviews, where emphasis was placed on consideration of individual cases, and generalisations concerning the inclusion or exclusion of specific patient groups were avoided. For only a minority (less than a third) does approval or rejection of assisted suicide not depend on the description of the situation of the person requesting it. Broadly speaking, the more clearly a purely somatic and terminal disease is present, the greater the acceptance of assisted suicide.

Ethical arguments used to justify or oppose physician-assisted suicide

The fact that a large majority of physicians do not question the acceptability of physician-assisted suicide was clearly demonstrated by the written survey. The qualitative interviews revealed a number of arguments used for the ethical justification of assisted suicide as a medical responsibility. These included, in particular, the alleviation of suffering as a goal of medicine, which may also be served in the last resort by assisted suicide. Here, the administration of a lethal dose of a drug is perceived as a humane form of dying in contrast to so-called violent methods of suicide. Apart from the alleviation of suffering, respect for patient autonomy is cited in the qualitative interviews as an ethical justification for physician-assisted suicide.

In the qualitative interviews, it was emphasised that the quality of the physician-patient relationship is important for appropriate assisted suicide. This means that the relationship should have existed for some time and be characterised by trust, and that, as well as medical expertise, the physician should have knowledge of the patient and his or her social/family environment. This knowledge – also rated as important by a vast majority in the written survey – was deemed necessary to permit evaluation of the eligibility criteria for assisted suicide specified in the professional code – in particular, whether the desire for suicide is well-considered and voluntary. In the qualitative interviews, a key role in this connection was assigned to the general practitioner. This impression was confirmed by the written survey: family medicine is the specialty which, given the high rate of participation in the survey, appears to take an above-average interest in the topic of assisted suicide (table 1). With regard to the appropriate role of physicians in the area of assisted suicide, what emerges as a common denominator for the great majority of respondents is the view that assisted suicide should always be undertaken on a voluntary basis. This excludes scenarios of emergency assisted suicide or an obligation to perform assisted suicide if all the specified criteria are met. The central importance attached to voluntariness and physician autonomy was frequently emphasised in the qualitative interviews.

Physicians’ potential readiness to be involved in a suicide

Physicians’ readiness to be involved in a suicide was explored in the questionnaire firstly in general terms and secondly via a detailed list of activities associated with assisted suicide. From the latter set of questions, it is evident that almost all physicians are prepared to advise, inform and continue to treat the person concerned. The vast majority are also prepared to evaluate the eligibility criteria for assisted suicide specified in the professional code. From a legal viewpoint, however, these actions do not form part of assisted suicide. Among the physicians surveyed, the study reveals a discrepancy between the reported readiness actually to participate in assisted suicide (29%) and the expressed potential readiness (43%). This difference is statistically significant and cannot be regarded as a chance result of the sample selected. A misunderstanding of what is meant by assisted suicide in each case can also be ruled out, since for both sets of questions the term was defined as the prescription or dispensing of a drug for the purpose of suicide. The authors interpret the discrepancy as evidence that assisted suicide is viewed as an exceptional situation in which one is not obliged to participate even if all the eligibility criteria are met. In other words, assisted suicide is a medical option which physicians do not wish to categorically rule out, but which they have reservations about actually pursuing. In this case, referring a patient to another physician who is prepared to perform assisted suicide or to an assisted suicide organisation – which around half the respondents would consider – may represent a compromise.

The discrepancy between reported readiness to actually participate in assisted suicide and expressed potential readiness could be also elaborated from another angle.1 Assisted suicide in Switzerland is a rare event. Most assisted suicides are performed by physicians who are members of right-to-die-organisations, not by physicians who work in hospitals, nursing homes or doctors’ surgeries. Accordingly, the lack of experiences and confrontation could be also a reason for the discrepancy in the physicians’ attitudes described above. Research also indicates that physicians are more reluctant to support assisted suicide when they have to take full and final responsibility for it, in contrast to nurses for example [14].

The end-of-life criterion as a necessary condition for physician-assisted suicide

As regards attitudes to the professional code, the picture that emerged from the survey is similar to the findings of the qualitative interviews: the respondents appeared to distinguish between different levels of behavioural norms and options. Thus, an individual may be personally opposed to assisted suicide and rule it out as an option for him/herself, while at the same time supporting physician-assisted suicide in the ethical guidelines which define a broader normative framework for the profession as a whole.

The written survey revealed a striking discrepancy with regard to the end-of-life criterion. According to the SAMS Guidelines, a necessary condition for the acceptability of assisted suicide is that the person concerned has a life expectancy of only a few days or weeks. A large majority of the respondents (74%) indicated that this condition should be maintained in the Guidelines (table 4). This contradicted the statements made concerning the acceptability of assisted suicide in specific clinical situations (fig. 1, table 3). In the evaluation of specific situations, it became clear that only a minority (10%) took the view that assisted suicide should be restricted to patients at the end of life. This proportion is low compared with a study carried out in 2008 [15, 16], where 57% of respondents said that physician-assisted suicide must be limited to terminally ill patients; in that study, however, the question was worded in much stronger terms, with participants being asked whether or not assisted suicide should be “morally condemned”. In our study, a majority of respondents (72%) also considered assisted suicide to be justifiable for patients in non-terminal stages of disease.

The discrepancy between the view that the end-of-life condition should be maintained in the SAMS Guidelines and the view that assisted suicide is also acceptable in non-terminal stages of disease also appeared at another point in the written survey. Whereas four-fifths of all respondents – including physicians fundamentally opposed to assisted suicide – said they were prepared to evaluate the criteria of decisional capacity (81%) and a well-considered desire for suicide (80%) specified in the professional code, the readiness to evaluate whether the person is near the end of life was considerably lower. Only 63% were prepared to do so. The proportions were particularly striking in the group potentially prepared to be involved in assisted suicide: almost all of this group (90%) would evaluate the criteria of decisional capacity and a well-considered desire, but only two-thirds (66%) would evaluate the end-of-life criterion. There was thus a minority – 12% of all respondents – that would be prepared to be involved in assisted suicide without evaluating all the criteria specified by the professional code.

These discrepancies concerning the end of life as a necessary condition for the acceptability of assisted suicide require an explanation. A terminological misunderstanding can be ruled out, as the meaning of “end of life” as understood by the SAMS (days to a few weeks before the onset of death) was explicitly defined several times in the questionnaire. As a possible explanation for the discrepancy, it is suggested that the end-of-life criterion specified in the SAMS Guidelines only represents an ideal solution for a small minority of respondents. The majority may support the criterion as a compromise, in order to prevent – depending on one’s basic attitude – a loosening or a tightening of the conditions in the professional code. However, this would also call into question the binding nature of the SAMS Guidelines in actual medical practice for the end-of-life condition.

Conclusions

The vast majority of physicians surveyed consider assisted suicide to be justifiable in principle, however, their support is strongly dependent on the specific clinical situation. The study indicates that even physicians expressing a potential readiness to perform assisted suicide themselves would not do so automatically if all the criteria for assisted suicide were met. Assisted suicide thus appears to be an exceptional situation, which physicians would only do on a voluntary basis.

The authors recommend that the current SAMS Guidelines regulating physician-assisted suicide in Switzerland should be reviewed with regard to the end-of-life criterion as a necessary condition for physician-assisted suicide. This also needs to be discussed because the end-of-life criterion is the key factor determining the inclusion or exclusion of certain groups of patients. The discrepancy identified in the written survey – between the view of a clear majority that assisted suicide is also acceptable for patients not at the end of life and the simultaneously expressed view that this criterion should be maintained in the SAMS Guidelines as a prerequisite for assisted suicide – is to be taken seriously as a sign of ambivalence in physicians’ attitudes to assisted suicide.

References

1 Sax A. Suizidhilfe – (k)eine ärztliche Aufgabe? Bericht von der Podiumsdiskussion der Schweizerischen Ärztezeitung vom 27. November 2012 in Basel. Schweiz Ärzteztg. 2013;94(4):108–11.

2 SAMW. Betreuung von Patientinnen und Patienten am Lebensende. Medizinisch-ethische Richtlinien der SAMW. Vom Senat der SAMW am 25. November 2004 genehmigt [cited 2015 Apr 2]. Available from: http://www.samw.ch .

3 SAMW. Probleme bei der Durchführung von ärztlicher Suizidhilfe: Stellungnahme der Zentralen Ethikkommission (ZEK) der SAMW. Von der ZEK am 20. Januar 2012 genehmigt [cited 2015 Apr 2]. Available from: http://www.samw.ch

4 Bosshard G, Broeckaert B, Clark D, Materstvedt L J, Gordijn B, Müller-Busch HC. A role for doctors in assisted dying? An analysis of legal regulations and medical professional positions in six European countries. J Med Ethics. 2008;34:28–32.

5 Hotz KP. Barbiturat – das Sterbemittel Natrium-Pentobarbital NaP. In: Wehrli H et al., editors. Der organisierte Tod: Sterbehilfe und Selbstbestimmung am Lebensende – Pro und Contra. Zürich: Orell Füssli; 2012. p. 233–42.

6 Peterková H. Sterbehilfe und die strafrechtliche Verantwortlichkeit des Arztes. Bern: Stämpfli; 2013.

7 Stratenwerth G, Wohlers W. Schweizerisches Strafgesetzbuch – Handkommentar. Bern: Stämpfli; 2013.

8 Trechsel S. Schweizerisches Strafgesetzbuch, Praxiskommentar. Zürich: Dike; 2008.

9 Löfmark R, Nilstun T, Cartwright C, Fischer S, van der Heide A, Mortier F, et al. Physicians’ experiences with end-of-life decision-making: Survey in 6 European countries and Australia. BMC Medicine. 2008;6(4).

10 Bosshard G, Fischer S, Bär W. Open regulation and practice in assisted dying: How Switzerland compares with the Netherlands and Oregon. Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132:527–34.

11 Fischer S, Bosshard G, Faisst K, Tschopp A, Fischer J, Bär W, et al. Swiss doctors’ attitudes towards end-of-life decisions and their determinants. A comparison of three language regions. Swiss Med Wkly. 2005;135: 370–76.

12 Burkhardt S, Wyss K. L’assistance au suicide en Suisse: la position des médecins. Revue Medicale Suisse. 2007;3:2861–64.

13 Schwarzenegger C, Manzoni P, Studer D, Leanza C. Einstellungen der Mediziner und Juristen sowie der Allgemeinbevölkerung zur Sterbehilfe und Suizidbeihilfe. In: Wehrli H et al., editors. Der organisierte Tod: Sterbehilfe und Selbstbestimmung am Lebensende – Pro und Contra. Zürich: Orell Füssli; 2012. p. 209–32.

14 Guedj M, Gibert M, Maudet A, Muñoz Sastre MT, Mullet E, Sorum PC. The acceptability of ending a patient’s life. J Med Ethics. 2005;31(6):311–17.

15 Pfister E, Biller-Adorno N. The reception and implementation of ethical guidelines of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences in medical and nursing practice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(11–12):160–7.

16 Pfister E, Biller-Adorno N. Physician-Assisted Suicide: Views of Swiss Health Care Professionals. Bioethical Inquiry. 2010;7:283–5.