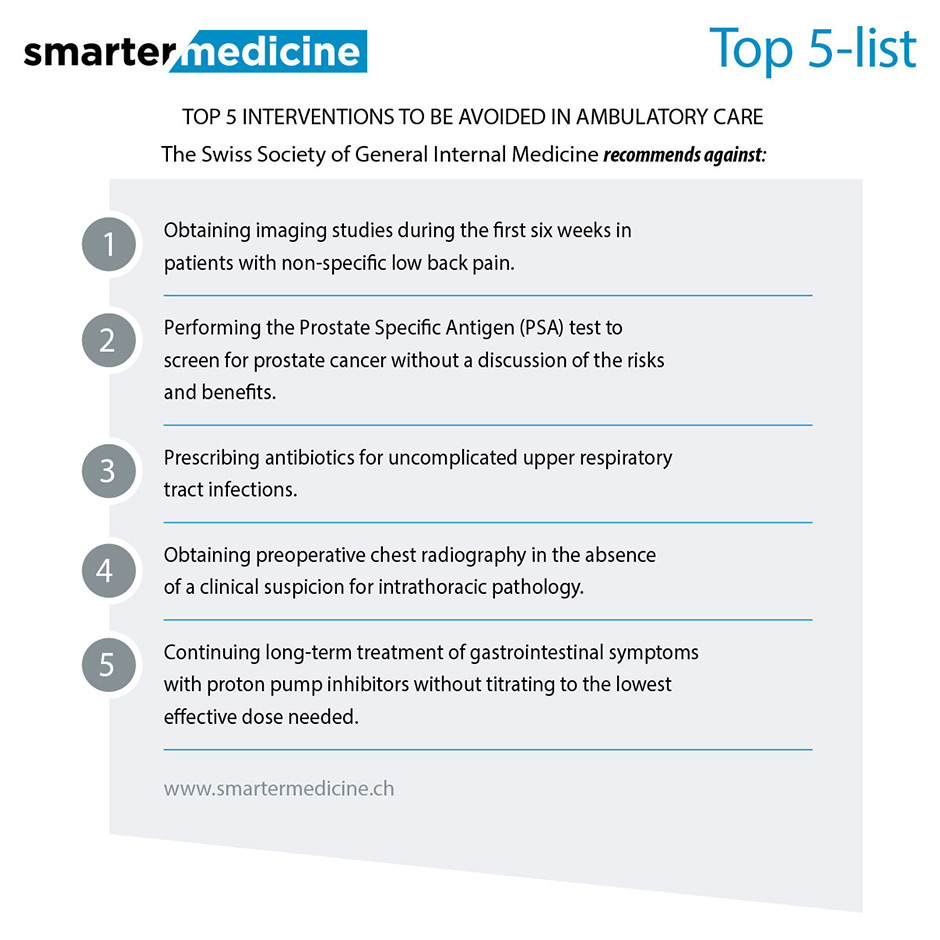

Figure

Top five list of the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine. May 2014.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14125

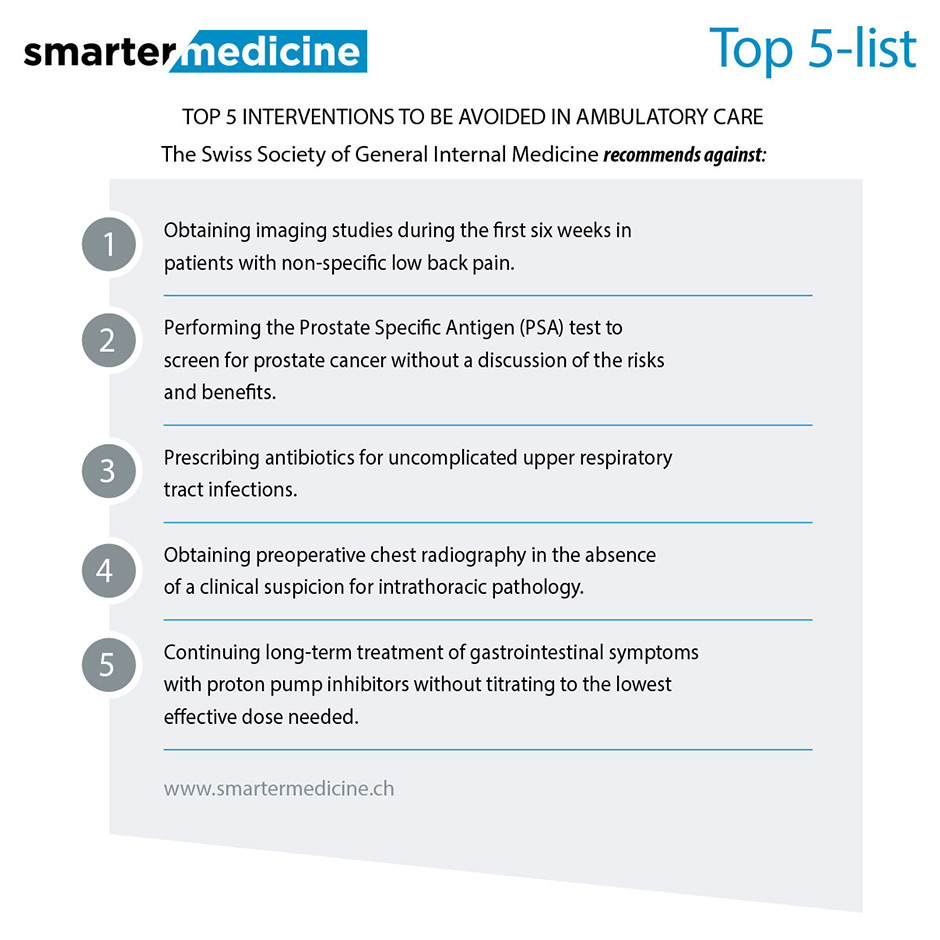

In May 2014, at the opening of its annual congress in Geneva, the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine launched a public campaign named “smarter medicine”. It listed five tests or treatments that are often prescribed in ambulatory general internal medicine, but that may not provide any meaningful benefit for at least some patients and that may carry the risk of generating harms and costs (fig. 1) [1].

Figure

Top five list of the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine. May 2014.

It is difficult to find a precise date or a starting point for the concept that some medical strategies may have no added value for patients, but rather may harm them and waste medical resources. Already in 1976, Ivan Illich wrote “The medical establishment has become a major threat to health” [2]. An editorial of the British Medical Journal (BMJ) published in 2002 by a journalist, Ray Moynihan, and Richard Smith, then Editor of the BMJ, entitled “Too much medicine? Almost certainly” [3], represents a milestone of this paradigm and launched the concept of “winding back the harms of over-diagnosis and over-treatment” [4].Then came the “choosing wisely” campaign in the USA, launched in 2012 and built on the efforts developed since 2009 by the National Physicians Alliance, funded by the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation. The Alliance guided representatives from three primary care specialists to develop “top five” lists of achievable changes in medical practice that might reduce risks and, possibly, costs [5]. Much less known, however, is the “disinvestment” strategy started in 1999 in the United Kingdom by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to support the National Health Services (NHS) in identifying “low value” activities that could be stopped, because of having a poor risk-benefit profile. Within 10 years, NICE identified 800 possible clinical interventions for potential disinvestment [6].

Echoing the “choosing wisely” campaign in the USA, in 2012 the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences issued a position paper named “sustainable medicine” in which it urged medical societies to list 10 strategies of proven limited benefit to decrease the burden of healthcare costs [7]; the Academy now takes an active role in supporting these societies to develop clinical guidelines [8].

All the initiatives listed above point towards a common goal: to decrease the use of medical strategies with no or with limited value to patients, either resulting from the routine non-evidence‒based prescription of tests or treatments, or from overdiagnosis and overtreatment.

NICE was established in 1999 principally so that the NHS would reimburse only pharmaceuticals and medical technologies considered clinically relevant and cost-effective. Thus, local NHS bodies were asked to fund only technologies that NICE had approved within the prior six months. After the UK Health Select Committee, the chief medical officer, Liam Donaldson, recommended that NICE “should be asked to issue guidance to the NHS on disinvestment, away from established interventions that are no longer appropriate or effective, or do not provide value for money” [9]. Andy Burnham, then Minister of Health, followed his recommendation and asked NICE to begin in 2006 a “pilot ineffective treatments programme” [10]. Many problems arose [6]: (i.) opponents of disinvestment pointed out the flaws of using average estimates of a clinical effect based on populations and argued that one specific intervention may be beneficial for an individual patient; (ii.) professional stakeholders became concerned that once an intervention was named as a possible candidate for disinvestment, its use would be prejudiced regardless of the final guidance; (iii.) economists argued that disinvestment may necessitate the use of costly alternatives; and, finally, (iv.) lack of data on usage made it impossible to guarantee that substantial savings would be made. The NICE experts had to agree with other international experiences that identifying and removing services can be difficult and very controversial [11]. The NICE pilot finally concluded that clinical guidelines would be the best way to identify disinvestment and to implement it; thus, NICE commissioned an annual report from the Cochrane Collaboration to identify reviews that concluded that an intervention was not recommended, and ended up offering on its website “do not do” recommendations” and “guidance” about what would save NHS money [12]. NICE efforts now concentrate on editing guidelines based on consensus techniques, which integrate the evidence from systematic reviews with social values and patient preferences [6]. Controversies about NICE are still ongoing in the UK, but advisory bodies have realised that much more information and evidence are necessary before they decide to ban tests or procedures.

In 2009, while trying to pass its Patient Affordable Care Act, the Obama administration called for the support of the healthcare related industries (insurance companies, pharmaceutical manufacturers, medical device makers, and hospitals) and of the physicians. All agreed to forego some profits, with the exception of the medical profession. They made no promises, but called for malpractice reform, with the suggestion that high healthcare costs were triggered by the legal but not the medical system [13].

In a legendary editorial, the ethicist Howard Brody wrote “A profession that has sworn to put the patient’s interest first cannot justifiably stand idly by and allow a legislation that would extend basic access to care to go down to defeat while refusing to contemplate any meaningful measures it might take to reduce health care costs” [14]. In the same editorial, he proposed that each specialty society commit itself immediately by setting up a “top five list” of “five diagnostic tests or treatments that are very commonly ordered by members of that specialty, that are among the most expensive services provided, and that have been shown by currently available evidence not to provide any meaningful benefit to at least some categories of patients for whom they are commonly ordered”. Almost simultaneously, the American Board of Internal Medicine awarded a grant to the National Physicians Alliance to develop and disseminate top-five lists that could be adopted by primary care providers (family medicine, internal medicine and paediatrics) [15]. The “less is more” movement was launched [16], with a commitment of the Editor of the Archives of Internal Medicine to publish a series of articles focused on top-five activities [17]. The “choosing wisely” campaign launched in 2012 took over and became supported by the American College of Physicians [18].

What are physicians’ views about their role in controlling healthcare costs? In 2009, the President of the American Medical Association (AMA) did not seem to consider that physicians could play a significant role in terms of cutting future medical costs [13]; some physicians share this view in Switzerland as well. However, in 2012 Tilburt et al conducted a mailed cross-sectional survey among 3,897 practicing physicians, all members of the AMA, to assess their attitudes towards, and perceived role in, the reduction of healthcare costs [19]. A total of 2,556 (65%) answered and scored their enthusiasm for 17 cost-containment strategies and agreement with an 11-measure cost-consciousness scale. Most physicians (76%) reported being aware of the costs of the tests/treatments they recommended; 79% agreed that they should adhere to clinical guidelines that discourage the use of care with only marginal benefit and 89% agreed that they should take a more prominent role in limiting the use of unnecessary tests.

Although similar data are currently lacking in Switzerland, this study shows that, at least in the USA, practicing physicians reported having some direct responsibility for addressing healthcare costs and expressed general agreement about several quality initiatives to reduce costs.

In a rubric on its website, named “Five things physicians and patients should question”, “choosing wisely” encourages physicians, patients and other healthcare stakeholders “to think and talk about medical tests and procedures that may be unnecessary, and in some instances can cause harm to help make wise decisions about the most appropriate care based on a patient’s individual situation” [5].

Interestingly enough, the “choosing wisely” initiative very early involved consumer associations, which developed and disseminated materials to patients through large consumer reports and consumer groups to encourage and help patients ask their physicians questions about tests and procedures that they may find unnecessary.

The “choosing wisely” initiative in the USA was widely advertised not only in the newspapers of the consumer associations, but also in the lay press. Similarly, the launching of the public campaign “smarter medicine” in May 2014, at the opening of the annual congress of the Swiss Society of General Internal Medicine in Geneva, was largely echoed by public Swiss Radio and Television in the four linguistic regions of Switzerland, as well as by private radio stations, and by the lay press [20–21].

The NICE experience demonstrates that, as elsewhere in the world [11], too much political, technocratic or administrative pressure may endanger strategies aimed at reducing unnecessary medical tests or procedures. Such pressures and stringent regulatory measures about pharmaceuticals and medical technologically, systematically trigger major controversies and opposition; they are unlikely to be accepted and to achieve substantial savings [10].

By contrast, opinion leaders, whether physicians, academic leaders or ethicists, may make a difference. No-one will ever forget the 2010 editorial of Howard Brody in the New England Journal of Medicine [14], or another paper that he published in the same journal in 2012 named “From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance”. In addition, such new paradigms should be advocated and supported by leading scientific or academic institutions, such as the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences [7, 8], in addition to being prioritised and implemented by medical specialties. Some preliminary data now show that physicians themselves agree that they should take a more prominent role in limiting the use of unnecessary tests [19].

The lay press should be involved early, so that slogans such as “less is more”, “choosing wisely” or “smarter medicine” be widely publicised, and not only their rationale. One of the strengths of the “choosing wisely” campaign resides in its partnership with the consumer associations. Consumer reports largely contribute to public education campaigns, which should be intense and sustained.

In summary, only intense networking will be able to disseminate the message that medical tests or treatments that do not provide any meaningful benefit and that may carry the risk of generating harms and unnecessary costs should be abandoned.

Politicians can undoubtedly contribute to the success of these strategies, but rather than putting physicians alone under pressure and setting up stringent regulatory measures, they should network with all stakeholders and put emphasis on a broader agenda, the one of improving quality and efficiency, and make sure that patients receive “the right care at the right time in the right way” [8].

1 Selby K, Cornuz J, Neuner-Jehle S, Perrier A, Zeller A, Meier CA, et al. “Smarter medicine”: 5 interventions à éviter en médecine interne générale ambulatoire. Schweizerische Aerzte Zeitung. 2014;2014:95:20. French

2 Illich I. Limits to medicine. London: Marion Boyars, 1976.

3 Moynihan R, Smith R. Too much medicine? Almost certainly. BMJ. 2002;324:859–60.

4 Glasziou P, Moynihan R, Richards T, Godlee F. Too much medicine; too little care. Time to wind back the harms of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. BMJ. 2013;346:f1271.

5 Choosing wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation. 2013 http://www.choosingwisely.org

6 Garner S, Littlejohns P. Disinvestment from low value clinical interventions: NICELY done? BMJ. 2011;343:d4519.

7 Sustainable Medicine. Position paper of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, 2012.

8 Amstad, Gaspoz JM, Zemp L. Guidelines and choosing wisely: to do’s and not to do’s. Schweizerische Aerzte Zeitung 2015;96(5):130–131. German.

9 Donaldson L. On the state of the public health: annual report of the chief medical officer 2005. Department of Health, 2005.

10 NICE. Disinvestment project plan, 20 February 2006. http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/whoweare//seniormanagementteam/meetings/2006/21february2006/disinvestment_project_plan_20_february_2006_version_1.jsp.

11 Elshaug AG, Hiller JE, Tunis SR, Moss JR. Challenges in Australian policy processes for disinvestment form existing, ineffective health care practices. Aust N Z Health Policy 2007;4:23.

12 NICE. Cost savings. http://www.nice.org.uk/aboutnice/whawedo/niceandthenhs/CostSaving.jsp.

13 Rohack JJ. American Medical Association president’s address the AMA House of Delegates, Houston, November 7, 2009 http://www.ama.assn.org/assets/meeting/mm/rohack-speech.pdf)

14 Brody H. Medicine’s ethical responsibility for Health Care Reform – The Top five list. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(4):283–85.

15 ABIM Foundation. Medical professionalism in the New Millenium: A Physican Charter 2002. http://www.abimfoundation.org/Professionalism/~/media/Files/Physician%20Charter.ashx http://www.abimfoundation.org/Professionalism/~/media/Files/Physician Charter.ashx .

16 The Good Stewardship Working Group. Online first / Less is more. The “Top 5” lists in primary care. Meeting the Responsibility of professionalism. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1385–90.

17 Grady D. The “Top 5” Health care activities for which less is more. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1390–91.

18 Volpp KG, Loewenstein G, Asch DA. Choosing wisely. Low-value services, utilization, and patient cost-sharing. JAMA. 2012;308(16):1635–6.

19 Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, Thorsteinsdottir B, James KM, Egginton JS, et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380–88.

20 Zuercher Caroline. Ces examens inutiles. La Société Suisse de Médecine Interne Générale déconseille cinq tests aux praticiens. Tribune de Genève, 15 mai 2014.

21 Sacco F. L’abus de médecine peut nuire à la santé. Le Temps, 21 novembre 2014. French.

22 Brody H. From an ethics of rationing to an ethics of waste avoidance. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(21):1949–51.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.