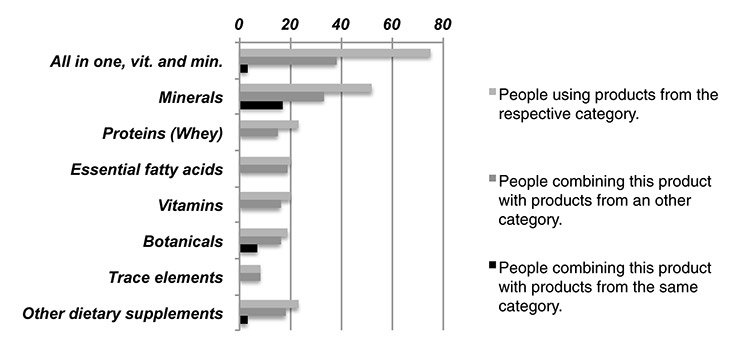

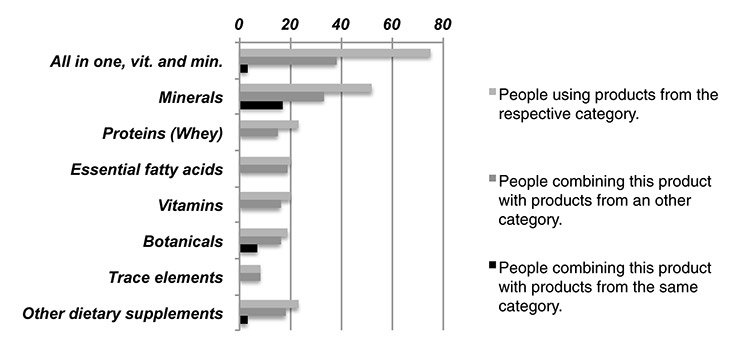

Figure 1

Categories and combinations of dietary supplements used (n = 147).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13807

In industrialised countries, diet is usually well balanced and contains sufficient nutrients, which is notably linked with the variety of foods available and a significant extension of enriched food products [1, 2]. In Switzerland, enriched food products doubled between 1996 and 2000, and increased by 30% in the following two years [3]. Nevertheless, dietary supplement (DS) use increased rapidly in recent years [4, 5] and reached a prevalence of 56.5% in the United States general population in 2001 [6], 49% in Italy in 2008 [7] and 26% in Lausanne, Switzerland in 2007 [8]. Although some populations benefit from DS intake [9], excessive intake might have deleterious effects [10].

DS consumers usually have an enhanced nutritional intake and adopt healthier lifestyles than nonconsumers [11–14]. However, recent data showed that DSs are also used by unhealthy users [13]. For healthy subjects without nutritional deficiency, some studies showed a reduction of cardiovascular disease or cancer incidence with a few substances such as selenium [15–17]. However, other studies, such as the Iowa women’s health study, questioned the long-term safety of dietary supplementation and revealed increased cancer incidence [18, 19] and overall mortality for supplement users [20]. Dietary supplementation can also provoke adverse events [21, 22] and interactions with medication [23], which may be especially problematic as 30% to 50% of nutritional supplement users declare that they do not inform their physician about their consumption [24, 25].

As DSs are so popular, it is important to know the reasons for choosing to take a DS and the perception of risks. A study of lifestyle characteristics found that 48% of DS users agreed that the use of the product is an easy way to stay healthy [14]. Reasons for DS use vary a great deal, with the most common being general improvements in health and wellbeing, such as feeling better (41%), improving overall energy levels (40.8%) and boosting immune systems (35.9%) [26]. One study by Neuhouser [27] showed that only 21% used supplements on the advice of health professionals and 41% used supplements because they made them feel good. Some participants thought that supplements could prevent cancer or heart disease. Up to 60% of users stated that a balanced diet did not contain enough nutrients. The belief that taking a DS has a beneficial effect on health could decrease the desire for other changes, like exercise activity or a healthy diet [28].

Given the scarcity of information in this area, our aim was to explore the category of DS used, motivations and risk perception of consumers in a convenient sample of the general population in the region of Lausanne, Switzerland, and to explore potential gender differences. Our hypothesis was that DS users were unaware of potential short- and long-term risks and that most of them did not take a specific supplement for a known deficiency, but rather one or more products with a mixture of nutrients for a variety of reasons. This preliminary study should provide more information for physicians and health authorities on consumers’ habits with DS use.

We used the definition published by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) [29], referring to the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA). Participants were recruited at the entrances of pharmacies, supermarkets and sports centres in different regions of the City of Lausanne, Switzerland. During short periods of 1 to 3 hours randomly spread between June and August 2011, all French-speaking customers were invited to participate in the study.

Data were collected by one researcher (DT) on site, using a semistructured interview lasting 2 to 5 minutes. The first part of the questionnaire recorded demographic data. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions on product identity (name, content or other information that allowed exact identification of the product such as packaging design or description of the advertisement), reason for use and sources of information, and a closed question on a subjective estimate of potential effects (yes, no, don’t know). We also asked about products consumed by household members, but only if the respondent was the buyer or the person who recommended the DS. The third and last part of the questionnaire concerned the perception of risks; the participants’ were asked to what extent they agreed with the following sentence: “the use of dietary supplements presents no risk” (agree, rather agree, rather disagree or disagree). Participants were then asked if and where they looked for information about possible risks, and if they informed their physicians about their DS use. They were also asked to estimate the monthly cost of their DS consumption. Participants’ answers to open questions were coded and then regrouped for data analysis.

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS Statistics 19 for Macintosh OS X (IBM). Quantitative variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Comparisons between males and females were made using chi-square tests. Statistical tests were performed at a two-sided 5% significance level. The study has been submitted to the ethics committee of the University of Lausanne, which approved running the survey as planned.

| Table 1:Description of the study group (n = 147). | ||

| n | ||

| Sex | Male | 58 |

| Female | 89 | |

| Age | <18 years | 8 |

| 18–30 years | 26 | |

| 31–45 years | 39 | |

| 46–60 years | 26 | |

| >60 years | 48 | |

| Interview location | Pharmacy | 49 |

| Supermarket | 54 | |

| Sports centre | 44 | |

Out of a total of 483 people contacted, 259 rejected participation and 105 were excluded for not taking dietary supplements within the last 12 months. The 119 included participants provided information on 147 users within their household (table 1). The acceptance rate was lowest in supermarkets (28%) and highest in sports centres (59%). Men refused participation more often than women (63% vs 48%).

Figure 1

Categories and combinations of dietary supplements used (n = 147).

The products most often consumed were all-in-one products containing a mixture of minerals and vitamins or products containing only minerals, followed by botanicals, protein products and products containing essential fatty acids. The interviewer noticed that DS users, especially all-in-one users, often ignored the substances contained in their DS.

Among the 147 users, 72 (49%) used one all-in-one product and 3 (2%) used two all-in-one products. Sixty-six (45%) subjects used one single product, containing one or multiple ingredients, 54 respondents (37%) used two and 26 (18%) regularly combined three supplements or more. There were numerous combinations of products (fig. 1). Most products were taken once daily. Estimated expenses were between CHF 2 and CHF 200 monthly per person, with a mean estimate of CHF 36.70 (±30.40). People used DSs for a variety of reasons. The most commonly cited reasons were to improve general health and wellbeing as well as fitness, or medical reasons. Thirty-one (21%) consumers did not know for at least one product what the purpose of their DS use was. Some participants mentioned common concerns such as fatigue (n = 22; 15%) and the desire to improve wellbeing (n = 24; 16%). Only 15 (10%) people clearly stated that they took DSs to prevent an illness. Protein-only products were exclusively used to improve fitness and products containing only minerals were especially often used for medical reasons. Products (n = 273) were recommended primarily by health professionals (physicians and pharmacists; n = 102; 37%) and peers (n = 62; 23%). Less often, people learned of them from print media (n = 30; 11%) or sales points (n = 28; 10%). The Internet was mentioned as primary source in only 8 (3%) cases.

Seventy-five percent of participants thought that dietary supplementation presents no or hardly any risk (table 2) and 39% stated that they looked for potential risks of the products they used. Five had no opinion or did not want to answer this question. There was a significant difference between male and female participants (table 3). Although men searched more often for potential risks (p <0.001), they turned less frequently to health professionals to obtain this information (p = 0.007). Concerns raised were limited to misuse and overdose: nobody questioned the long-term safety of a correctly used product. Forty-nine percent of participants stated that their physicians were informed about their consumption. Male participants shared this information significantly less frequently with their physicians than female participants (p = 0.008).

| Table 2: Risk perception. Answer to the statement “the use of dietary supplements does not present any risks” (n = 114). | ||

| n | % | |

| I agree | 54 | 47.4% |

| I rather agree | 32 | 28.1% |

| I rather disagree | 13 | 11.4% |

| I disagree | 15 | 13.2% |

| Table 3: Gender differences in attitudes to dietary supplements. | |||

| Female | Male | p-value | |

| Searched for potential risks (n = 118) | 21 (28%) | 25 (60%) | <0.001 |

| Turned to health professionals to get information (n = 46) | 10 (48%) | 3 (12%) | 0.007 |

| Shared information about consumption with their physicians (n = 119) | 44 (57.9%) | 14 (32.6%) | 0.008 |

The aim of this study was to explore categories, motivations and risk perception of DS use in Switzerland in a convenient nonclinical sample of the general population. As in our study, a study in Italy showed that vitamins and minerals were the most commonly used DSs [7]. According to other studies [30–32], the majority of respondents used products containing a variety of substances. Giammaroli showed that 44% of DS users used only one category of food supplement and 54% were multiple users [7]. We noticed during the interviews that all-in-one DS users especially often ignored the substances contained in their DS. They just desired a DS and did not care about its exact content. A respondent using vitamins stated: “it just feels good in the morning [to take my vitamins]”. Six respondents over 60 years old reported that they felt compelled to take dietary supplements because of their age. More than half of DS users stated that they felt positive effects from the intake of DSs. As in other studies that explored risk perception of DS among specific populations [24, 33], our study also showed that risk perception is generally low. This leads to positive perceived evaluations of risk-benefit [34, 35] even if there is no clear scientific evidence for the benefits of many DSs. They are often used on a “if it doesn’t help, it won’t harm” basis, with the users ignoring potential risks. Blendon [26] showed that more than one-third of supplement users (35.9%) had not told their physician that they used any DS. Our results also showed that physicians could miss information about DS use if they do not ask their patients. As shown in figure 1, three DS users combined all-in-one products with other DSs and even with another all-in-one DS, which could lead to an excess of one or another substance. Physicians could point out this risk to their patients, especially to men who seemed not to speak spontaneously with their physician about DSs, and help them to read the ingredients of the DS.

Our study showed that men discussed DS use with their physician less frequently than female participants. Many studies showed that men seek professional help less frequently than women and, when they do seek help, they ask fewer questions [36]. It seems to be the same for DS use. Our results showed that women searched for potential risks less frequently than men. A potential explanation could be that they already received enough risk information from their physician.

There are some limitations to our exploratory study. First, our convenient sample was relatively small and we faced refusals from potential participants, thus we were not able to define specific profiles of users nor to draw any conclusion regarding the representativeness of our sample. For example, participants recruited at sport centres are more likely to belong to the healthy group of DS users [37]. We made no distinction between prescribed supplements linked with medical conditions (for example, calcium supplementation) and other types of supplements, as subjects sometimes did not know whether a supplement was prescribed by their physician or not.

There are some lessons that can be learned from this study. As DS consumption is common in our society and patients often do not speak spontaneously about DSs during a consultation, physicians should be trained to assess actively the use of supplements by their patients, not only to prevent interactions with medication but also to evaluate the patients’ knowledge, needs and perceptions in this area. According to the current scientific data for healthy subjects, physicians should also discuss the high benefit for health of some moderate exercise [38] and balanced diet in comparison with DS use. Also, owing to concerns regarding the long-term safety of such products [18-20], physicians should warn their patients about the potential negative impact of a regular consumption of high doses of products containing multiple components, whose effects are not well understood. Finally, health authorities should develop more resources that could help the public and professionals to obtain factual information about the benefits and risks of DSs. Future studies with larger samples should, for example, focus on potential interactions of DSs with drugs used by patients, or on physicians’ attitudes toward DS use.

1 Beer M. Das Functional-Food-Konzept. In: BAG O, UFSP and SFOPH, ed. Fünfter Schweizerischer Ernährungsbericht/Cinquième rapport sur la nutrition en Suisse. Bern: Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique 2005:709–14. German

2 Beer-Borst S, M. C, Morabia A. Die Bedeutung von «Functional Food» in der Ernährung der erwachsenen Genfer Bevölkerung – eine Bestandesaufnahme. In: BAG O, UFSP and SFOPH, ed. Fünfter Schweizerischer Ernährungsbericht/Cinquième rapport sur la nutrition en Suisse. Bern: Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique 2005:751–66. German

3 Wälti M, Jacob S. Angereicherte Lebensmittel in der Schweiz. In: BAG O, UFSP and SFOPH, ed. Fünfter Schweizerischer Ernährungsbericht/Cinquième rapport sur la nutrition en Suisse. Bern: Office Fédéral de la Santé Publique 2005:767–78. German

4 Lockwood GB. The hype surrounding nutraceutical supplements: do consumers get what they deserve? Nutrition. 2007;23(10):771–2.

5 Balluz LS, Kieszak SM, Philen RM, Mulinare J. Vitamin and mineral supplement use in the United States. Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(3):258–62.

6 Balluz LS, Okoro CA, Bowman BA, Serdula MK, Mokdad AH. Vitamin or supplement use among adults, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 13 states, 2001. Public Health Rep. 2005;120(2):117–23.

7 Giammarioli S, Boniglia C, Carratu B, Ciarrocchi M, Chiarotti F, Mosca M, et al. Use of food supplements and determinants of usage in a sample Italian adult population. Public Health Nutr. 2012:1–14.

8 Marques-Vidal P, Pecoud A, Hayoz D, Paccaud F, Mooser V, Waeber G, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of vitamin or dietary supplement users in Lausanne, Switzerland: the CoLaus study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63(2):273–81.

9 Beitz R, Mensink GB, Fischer B, Thamm M. Vitamins – dietary intake and intake from dietary supplements in Germany. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56(6):539–45.

10 Penniston KL, Tanumihardjo SA. Vitamin A in dietary supplements and fortified foods: too much of a good thing? J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103(9):1185–7.

11 Harrison RA, Holt D, Pattison DJ, Elton PJ. Are those in need taking dietary supplements? A survey of 21 923 adults. Br J Nutr. 2004;91(4):617–23.

12 Kirk SF, Cade JE, Barrett JH, Conner M. Diet and lifestyle characteristics associated with dietary supplement use in women. Public Health Nutr. 1999;2(1):69–73.

13 van der Horst K, Siegrist M. Vitamin and mineral supplement users. Do they have healthy or unhealthy dietary behaviours? Appetite. 2011;57(3):758–64.

14 de Jong N, Ocke MC, Branderhorst HA, Friele R. Demographic and lifestyle characteristics of functional food consumers and dietary supplement users. Br J Nutr. 2003;89(2):273–81.

15 Bleys J, Navas-Acien A, Guallar E. Serum selenium levels and all-cause, cancer, and cardiovascular mortality among US adults. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(4):404–10.

16 Holmquist C, Larsson S, Wolk A, de Faire U. Multivitamin supplements are inversely associated with risk of myocardial infarction in men and women – Stockholm Heart Epidemiology Program (SHEEP). J Nutr. 2003;133(8):2650–4.

17 Giovannucci E, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Hunter DJ, Fuchs C, Rosner BA, et al. Multivitamin use, folate, and colon cancer in women in the Nurses’ Health Study. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129(7):517–24.

18 Ebbing M, Bonaa KH, Nygard O, Arnesen E, Ueland PM, Nordrehaug JE, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality after treatment with folic acid and vitamin B12. JAMA. 2009;302(19):2119–26.

19 Klein EA, Thompson IM, Jr., Tangen CM, Crowley JJ, Lucia MS, Goodman PJ, et al. Vitamin E and the risk of prostate cancer: the Selenium and Vitamin E Cancer Prevention Trial (SELECT). JAMA. 2011;306(14):1549–56.

20 Mursu J, Robien K, Harnack LJ, Park K, Jacobs DR, Jr. Dietary supplements and mortality rate in older women: the Iowa Women's Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(18):1625–33.

21 Palmer ME, Haller C, McKinney PE, Klein-Schwartz W, Tschirgi A, Smolinske SC, et al. Adverse events associated with dietary supplements: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;361(9352):101–6.

22 Hathcock JN. Vitamins and minerals: efficacy and safety. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997;66(2):427–37.

23 Gershwin ME, Borchers AT, Keen CL, Hendler S, Hagie F, Greenwood MR. Public safety and dietary supplementation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1190:104–17.

24 Blendon RJ, DesRoches CM, Benson JM, Brodie M, Altman DE. Americans’ views on the use and regulation of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(6):805–10.

25 Hensrud DD, Engle DD, Scheitel SM. Underreporting the use of dietary supplements and nonprescription medications among patients undergoing a periodic health examination. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74(5):443–7.

26 Blendon Rj BJMBMDWKJ. Users' views of dietary supplements. Arch Intern Med. 2012:1–2.

27 Neuhouser ML, Patterson RE, Levy L. Motivations for using vitamin and mineral supplements. J Am Diet Assoc. 1999;99(7):851–4.

28 Chiu YW, Weng YH, Wahlqvist ML, Yang CY, Kuo KN. Do registered dietitians search for evidence-based information? A nationwide survey of regional hospitals in Taiwan. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2012;21(4):630–7.

29 National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM). Dietary and Herbal Supplements. [Internet] 2011 Apr 01 [cited 2011 May 9]; Available from: http://nccam.nih.gov/health/supplements/

30 Radimer K, Bindewald B, Hughes J, Ervin B, Swanson C, Picciano MF. Dietary supplement use by US adults: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2000. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160(4):339–49.

31 Kennedy J. Herb and supplement use in the US adult population. Clin Ther. 2005;27(11):1847–58.

32 Brown BH. Perceptions Related to Dietary Supplements among College Students: University of Tennessee, Knoxville; 2010.

33 O'Dea JA. Consumption of nutritional supplements among adolescents: usage and perceived benefits. Health Educ Res. 2003;18(1):98–107.

34 Centre for Medicines Research (Surrey England). Workshop (1985: Ciba Foundation), Walker SR, Asscher AW. Medicines and risk/benefit decisions. Lancaster, Boston: MTP Press; 1987.

35 Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences CIOMS. Benefit-Risk Balance for Marketed Drugs: Evaluating Safety Signals. Geneva: CIOMS; 1998.

36 Addis ME, Mahalik JR. Men, masculinity, and the contexts of help seeking. Am Psychol. 2003;58(1):5–14.

37 Mullie P, Clarys P, Hulens M, Vansant G. Socioeconomic, health, and dietary determinants of multivitamin supplements use in Belgium. Int J Public Health. 2011;56(3):289–94.

38 Myers J, Kaykha A, George S, Abella J, Zaheer N, Lear S, et al. Fitness versus physical activity patterns in predicting mortality in men. Am J Med. 2004;117(12):912–8.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.