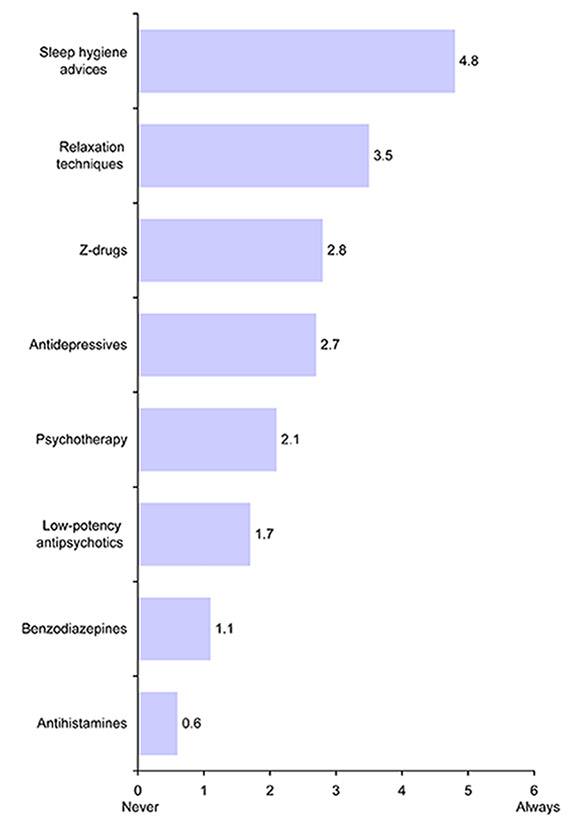

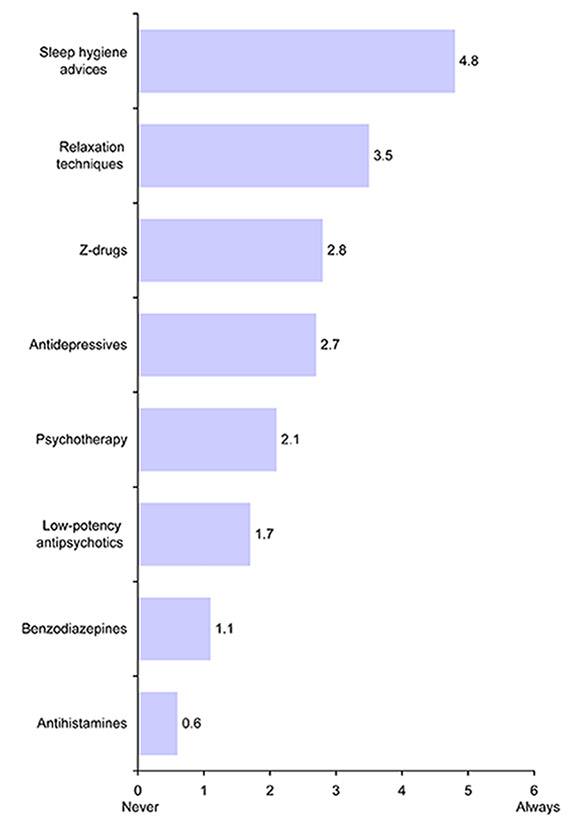

Figure 1

Use of different treatments for patients with insomnia.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2013.13745

In many countries including Germany the use of benzodiazepine hypnotics continues to fall, while a substantial increase has occurred in prescribing newer non-benzodiazepines, zolpidem and zopiclone (“Z-drugs”) [1–8]. However, there is a lack of evidence on differences in clinical effectiveness and safety between short-acting benzodiazepines and Z-drugs for treating insomnia [9–11]. The reasons for this gap between the available evidence and physicians prescribing behaviour have only been rarely assessed. In a survey of 84 British general practitioners (GPs), Siriwardena et al. found that Z-drugs were attributed with greater benefits and less side effects compared to benzodiazepines [12]. Z-drugs were also believed to be safer for more elderly patients, which also contradicts the current evidence. For persons aged 60 years and older, a meta-analysis found that the benefits of hypnotics are modest at best and are outweighed by the increased risks [13]. However, the study of Siriwardena et al. [12] is the only work published regarding GPs’ perceptions of the benefits and risks of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, and this question has not been addressed in a larger sample or another country.

Thus the aim of this study was to fill this gap and to compare perceptions of benefits and harms of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs of German GPs.

In Germany, about 55,000 GPs work in the outpatient sector. A questionnaire survey was mailed to a simple random sample of 1,350 German GPs between May and June 2012. Several strategies shown by a recent Cochrane review to increase response to postal questionnaires were applied [14]. Those include pre-notification, a short questionnaire, follow-up contact, providing a second copy of the questionnaire at follow-up, personalised postcards and letters, hand-written signatures, and academic origin of the study. A postcard announcement was sent one week before the two-sided questionnaire including a pre-addressed return envelope was mailed out. Three weeks later, a reminder including another copy of the questionnaire as well as a pre-addressed return envelope was sent to all non-responders. No further actions were taken and no financial incentives were provided.

Figure 1

Use of different treatments for patients with insomnia.

The questionnaire consisted of four sections concerning treatment of insomnia, perceptions of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs, private prescriptions of hypnotics and demographic information. The GPs were asked to indicate on a seven-point Likert scale (0 = never to 6 = always) how often they use several pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments for insomnia. This question was also applied by Sivertsen et al. [8]. To study perceptions on benefits and harms, the same questions consisting of 12 items were asked on both benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Each of these items was rated on a five-point Likert scale. For instance, answers on how participants rate the effectiveness of these hypnotics ranged from “lacking/ very small” to “very strong”. The items presented in table 2 and table 3 were adopted from Siriwardena et al. [12].

For the sample size calculation, the comparisons of the benefits and harms of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs rated on the five-point Likert scale were used. Aiming for a power of 95% at an α error of 1% to detect a mean difference of 0.24 (Cohen’s d = 0.2) with a standard deviation of 1.2, a total of 470 participants were needed. Taking into account a response of 35% would result in a sample size of at least 1,343. Therefore, questionnaires were mailed out to 1,350 GPs.

Baseline characteristics are presented as percentages or as means with standard deviation. The main interest of this study was on differences in perceptions of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. Wilcoxon signed rank test for paired observations was used for comparison between groups. Responses of the five-point Likert scales are presented within three categories. Due to multiple testing, only p values ≤0.01 were considered statistically significant.

All statistical analyses were performed with SAS for Windows version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Out of 1,350 questionnaires sent out, 458 were returned (response 33.9%). Baseline characteristics are presented in table 1. The mean age of the respondents was 53.3 years and 59.4% of them were male. On average, they had been in practice for 16.3 years.

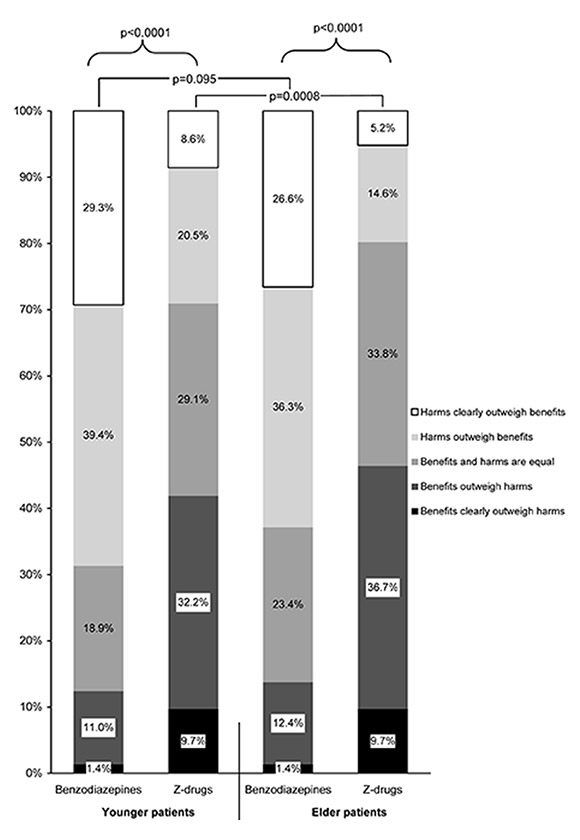

Figure 2

Perceptions of GPs on overall benefits and harms of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs in younger and in elderly patients.

As shown in figure 1, relaxation techniques and sleep hygiene advice were the most common types of treatment for insomnia. However, Z-drugs were the most prescribed pharmacological interventions and benzodiazepines were used much less frequently.

Participants perceived that Z-drugs were significantly more effective in terms of reduced night-time waking, feelings of being rested on waking and improved daytime functioning than benzodiazepines (p <0.0001 for all comparisons), but not in terms of reduced time to get to sleep and increased total sleep time (table 2). As shown in table 3, all studied side effects were believed to be significantly less often for patients receiving Z-drugs (p <0.0001 for all comparisons). For instance, whereas 73.4% and 80.4% answered that tolerance and withdrawal effects on stopping occur often or very often/ always respectively on benzodiazepines, these values were only 30.6% and 28.7% respectively for Z-drugs.

GPs perceived that Z-drugs have a much better overall ratio of benefits and harm as compared to benzodiazepines both in younger and elder patients (fig. 2). The ratio of benefits and harm of benzodiazepines was believed to be similar for younger and elder patients (p = 0.095). For Z-drugs, it was more often believed that harms outweigh benefits in younger than in elder patients (29.1% vs. 19.8%; p = 0.0008).

| Table 1: Baseline characteristics of participating GPs (n = 458). | |

| Baseline characteristics | Distribution* |

| Mean age, in years (SD) | 53.3 (8.7) |

| Age groups, in years | |

| <45 | 16.7% |

| 45–54 | 38.9% |

| 55–64 | 34.9% |

| 65+ | 9.6% |

| Sex | |

| Male | 59.4% |

| Female | 40.6% |

| Region of practice | |

| East | 18.4% |

| West | 81.6% |

| Type of practice | |

| Single-handed practice | 51.9% |

| Group practice | 45.3% |

| Others | 2.9% |

| Mean years in practice (SD) | 16.3 (9.7) |

| *n varies due to missing data. | |

| Table 2: Perceptions of GPs on the benefits of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. | |||||||

| Associated benefit | Benzodiazepines | Z-drugs | p-value | ||||

| Lacking/ very small or small | Moderate | Strong or very strong | Lacking / very small or small | Moderate | Strong or very strong | ||

| Reduced time to get to sleep | 7.3% | 24.6% | 68.2% | 2.5% | 26.6% | 70.9% | 0.038 |

| Reduced night-time waking | 10.9% | 43.2% | 45.9% | 4.3% | 40.7% | 55.0% | <0.0001 |

| Increased total sleep time | 19.4% | 44.2% | 36.3% | 14.2% | 46.3% | 39.5% | 0.036 |

| Feelings of being rested on waking | 57.7% | 36.9% | 5.4% | 15.6% | 46.6% | 37.8% | <0.0001 |

| Improved daytime functioning | 57.5% | 36.2% | 6.3% | 22.0% | 46.8% | 31.2% | <0.0001 |

| Table 3: Perceptions of GPs on the side effects of benzodiazepines and Z-drugs. | |||||||

| Frequency of side effect | Benzodiazepines | Z-drugs | p-value | ||||

| Never / very rarely or rarely | Occasionally | Often or very often / always | Never / very rarely or rarely | Occasionally | Often or very often / always | ||

| Tolerance (decreased responsiveness) | 5.4% | 21.2% | 73.4% | 29.5% | 39.9% | 30.6% | <0.0001 |

| Withdrawal effects on stopping | 5.4% | 14.2% | 80.4% | 33.6% | 37.7% | 28.7% | <0.0001 |

| Craving | 1.6% | 9.3% | 89.2% | 15.8% | 27.5% | 56.7% | <0.0001 |

| Confusion | 30.5% | 49.6% | 20.0% | 73.6% | 22.5% | 3.9% | <0.0001 |

| Falls | 31.6% | 49.7% | 18.8% | 72.8% | 23.3% | 3.9% | <0.0001 |

Although there is no compelling evidence for clinically relevant differences in effectiveness and safety between short-acting benzodiazepines and Z-drugs [9–11], German GPs perceived that Z-drugs were more effective compared to benzodiazepines. These results are very well in line with the survey conducted by Siriwardena et al. [12]. Interestingly, in both studies no statistically significant differences between benzodiazepines and Z-drugs were found for the item “reduced time to get to sleep”. About 70% of the GPs in both studies believed that hypnotics have a strong or very strong influence on this sleep variable and the effects on total sleep time were rated much smaller. On the contrary, in a meta-analysis on benzodiazepines in insomnia, Holbrook et al. found a non-significant decreased sleep latency by 4.2 minutes but a significantly increased total sleep duration by 61.8 minutes when compared to a placebo [15]. The finding that GPs attribute much fewer side effects to Z-drugs compared to benzodiazepines is also well in line with the results of Siriwardena et al. [12]. Germane to this, GPs perceived that Z-drugs have a better overall ratio of benefits and harms both in younger and elder patients. However, this measure was rated similarly for benzodiazepines independently of age and Z-drugs were even believed to have a higher benefit in elder than in younger patients. This is also not supported by the current evidence. As a rough comparison, the number needed to treat for improved sleep quality was 13 while the number needed to harm for any adverse event (mainly psychomotor and cognitive side effects and fatigue) was 6 for patients aged 60 years and older in the meta-analysis of Glass et al. [13].

An overestimation of the true effectiveness of hypnotics as well as the perception of fewer side effects of Z-drugs might lead to a more frequent use. In this study, Z-drugs were the most prescribed pharmacological interventions and benzodiazepines were used less often. This finding is quite in line with the results of a survey of GPs in Norway [8]. More positive perceptions might also be a reason for long-term use of Z-drugs. In a Danish as well as a British study, about 9 out of 10 users of Z-drugs received prescriptions for periods longer than 4 weeks [1, 7]. On the contrary, guidelines recommend that treatment with hypnotics should not be continued beyond 4 weeks [10, 11]. This discrepancy might be due to the fact that many patients suffer from chronic insomnia due to a lack of readily available alternatives. Although cognitive-behavioural therapy has shown long-term improvements for up to 12–24 months in head-to-head studies [16] and it is also effective in the elderly [17, 18], this intervention is comparably time-consuming and patients need to be seen by a psychotherapist. The average waiting time for a first psychotherapy appointment was rated by the participating GPs in this study to be 13.5 weeks (with a median of 12 weeks). This seems to be another barrier to implementation of evidence and guidelines on hypnotics. In certain situations prescribing hypnotics provides GPs with an opportunity to “do something” [19]. Further research in this context should focus on reasons for perceptions not supported by current evidence and barriers to implementation of guidelines.

A major strength of this work was that a large sample of German GPs could be studied. However, this increases the likelihood that even small differences will appear significant and this should be considered when interpreting the findings of this study. A limitation of this survey is the response of only 33.9%, which might lead to selection bias. However, this is quite comparable with other recently published surveys of German GPs with responses ranging between 23.3% and 46.1% [20–25]. Furthermore, as compared with the total sample, respondents did not differ with respect to sex (with 61.4% vs. 59.4% males) and region of practice (with 81.3% vs. 81.6% working in the West). Another source of bias might be social desirability when studying GPs perceptions on psychotropic substances that have the potential to cause dependence and tolerance. A further criticism refers to the fact that questions on perceptions on benefits and side effects were not divided into short-term and long-term use. However, this was also not done in the study of Siriwardena et al. [12] and one aim was to compare results of both surveys.

In conclusion, German GPs’ perceptions of benefits and side effects of Z-drugs and bezodiazepines were quite comparable to a British study conducted 7 years before. GPs perceived that Z-drugs were more effective and safer compared to benzodiazepines and that the overall ratio of benefits and harms in the elderly was no worse than in younger patients, which is not supported by current evidence. Physicians should consider the lack of difference between these types of drugs and the importance of restricting hypnotic prescriptions for short periods of time. This underlines the importance of implementing evidence and guidelines into clinical practice.

The questionnaire is provided in the appendix (PDF).

Acknowledgement: I thank all participating GPs for their support, and Dr. Roland Windt, Melanie Tamminga and Tim Jacobs for their help in conducting this study. We are grateful to Prof. Niroshan Siriwardena who provided a copy of his questionnaire developed for his survey.

1 Andersen AB, Frydenberg M. Long-term use of zopiclone, zolpidem and zaleplon among Danish elderly and the association with sociodemographic factors and use of other drugs. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(4):378–85.

2 Johnell K, Fastbom J. The use of benzodiazpines and related drugs amongst older people in Sweden: associated factors and concomitant use of other psychotropics. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24(7):731–8.

3 Hausken AM, Furu K, Skurtveit S, Engeland A, Bramness JG. Starting insomnia treatment: the use of benzodiazepines versus z-hypnotics. A prescription database study of predictors. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(3):295–301.

4 Hoffmann F, Glaeske G, Scharffetter W. Zunehmender Hypnotikagebrauch auf Privatrezepten in Deutschland. Sucht. 2006;52(6):360–6.

5 Hollingworth SA, Siskind DJ. Anxiolytic, hypnotic and sedative medication use in Australia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(3):280–8.

6 Kassam A, Carter B, Patten SB. Sedative hypnotic use in Alberta. Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(5):287–94.

7 Siriwardena AN, Qureshi MZ, Dyas JV, Middleton H, Orner R. Magic bullets for insomnia? Patients’ use and experiences of newer (Z drugs) versus older (benzodiazepine) hypnotics for sleep problems in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(551):417–22.

8 Sivertsen B, Nordhus IH, Bjorvatn B, Pallesen S. Sleep problems in general practice: a national survey of assessment and treatment routines of general practitioners in Norway. J Sleep Res. 2010;19(1 Pt 1):36–41.

9 Dündar Y, Boland A, Strobl J, Dodd S, Haycox A, Bagust A, et al. Newer hypnotic drugs for the short-term management of insomnia: a systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8(24):1–125.

10 DGSM – Deutsche Gesellschaft für Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin. S3-Leitlinie Nicht erholsamer Schlaf/Schlafstörungen. Somnologie. 2009;13(Supplement 1):4–160.

11 NICE – National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of zaleplon, zolpidem and zopiclone for the short-term management of insomnia. Technology Appraisal Guidance 77. NICE, London, 2004.

12 Siriwardena AN, Qureshi Z, Gibson S, Collier S, Latham M. GPs’ attitudes to benzodiazepine and ‘Z-drug’ prescribing: a barrier to implementation of evidence and guidance on hypnotics. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56(533):964–7.

13 Glass J, Lanctôt KL, Herrmann N, Sproule BA, Busto UE. Sedative hypnotics in older people with insomnia: meta-analysis of risks and benefits. BMJ. 2005;331(7526):1169.

14 Edwards PJ, Roberts I, Clarke MJ, Diguiseppi C, Wentz R, Kwan I, et al. Methods to increase response to postal and electronic questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):MR000008.

15 Holbrook AM, Crowther R, Lotter A, Cheng C, King D. Meta-analysis of benzodiazepine use in the treatment of insomnia. CMAJ. 2000;162(2):225–33.

16 Riemann D, Perlis ML. The treatments of chronic insomnia: a review of benzodiazepine receptor agonists and psychological and behavioral therapies. Sleep Med Rev. 2009;13(3):205–14.

17 Buysse DJ, Germain A, Moul DE, Franzen PL, Brar LK, Fletcher ME, et al. Efficacy of brief behavioral treatment for chronic insomnia in older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(10):887–95.

18 Sivertsen B, Omvik S, Pallesen S, Bjorvatn B, Havik OE, Kvale G, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy vs zopiclone for treatment of chronic primary insomnia in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;295(24):2851–8.

19 Anthierens S, Habraken H, Petrovic M, Christiaens T. The lesser evil? Initiating a benzodiazepine prescription in general practice: a qualitative study on GPs’ perspectives. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2007;25(4):214–9.

20 Behmann M, Schmiemann G, Lingner H, Kühne F, Hummers-Pradier E, Schneider N. Job satisfaction among primary care physicians: results of a survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(11):193–200.

21 Berg-Beckhoff G, Heyer K, Kowall B, Breckenkamp J, Razum O. The views of primary care physicians on health risks from electromagnetic fields. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(46):817–23.

22 Joos S, Musselmann B, Szecsenyi J, Goetz K. Characteristics and job satisfaction of general practitioners using complementary and alternative medicine in Germany – is there a pattern? BMC Complement Altern Med. 2011;11:131.

23 Karbach U, Schubert I, Hagemeister J, Ernstmann N, Pfaff H, Höpp HW. Physicians’ knowledge of and compliance with guidelines: an exploratory study in cardiovascular diseases. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011;108(5):61–9.

24 Schneider N, Engeser P, Behmann M, Kühne F, Wiese B. Spezialisierte ambulante Palliativversorgung. Die Erwartungen von Hausärzten. Schmerz. 2011;25(2):166–73.

25 Unrath M, Zeeb H, Letzel S, Claus M, Escobar PN. Identification of possible risk factors for alcohol use disorders among general practitioners in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:w13664.

Funding / potential competing interests: This work is funded by a grant of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG; project funding reference number HO 4782/1-1). The author declares no competing interests.

Ethical approval: The ethics committee of the University of Bremen advised that an ethical approval was not required for this study (e mail dated 4 May 2011).