Figure 1

Medical sites and units belonging to the Division of Primary Care Medicine.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13620

An observational pilot study

Ambulatory care is a mandatory component of post-graduate training in general internal medicine, where residents learn outpatient management of acute and chronic diseases, prevention, health promotion and patient-centreed care, with the opportunity to build longitudinal relationships with their patients [1, 2]. The outpatient setting is considered to be the place where patients now receive most of their acute, chronic and preventive care [3]. The shift of care from inpatient to outpatient settings observed in the last decade increased the importance and attractiveness of education in ambulatory practice, especially in the USA and Switzerland, where training traditionally focused on hospital settings [4, 5].

In Switzerland, residents are required to train for a minimum of 6 months in ambulatory medicine, generally after having spent 2 years in hospital settings, in order to obtain the new title of specialist in general internal medicine, formerly separated into general or internal medicine [6].

In Switzerland, most ambulatory training in general internal medicine still takes place in the outpatient clinics of academic medical centres for historical reasons. Vocational training in private medical practices started in the 1990’s [7], and is highly valued by both trainees and trainers [8]: more than 95% of them reported that vocational training improved their knowledge and skills needed in primary care and more than 50% of trainees considered vocational training to better fit with their professional goals than hospital training [8]. However, limited financing and availability of training positions make it impossible to accommodate all candidates [9].

Academic medical centres experience three main challenges in training residents in ambulatory care. First, residents are exposed to a complex patient population in terms of medical and psychosocial issues, which may not be representative of the patients seen in private practices. In the USA, academic postgraduate training sites care for more vulnerable populations, such as Afro-Americans, Latinos, as well as Medicare or Medicaid patients [10]. Medical problems are often complicated by poverty, illiteracy, mental illness and many other cultural, social and economic challenges [3]. The situation is similar in Switzerland, where academic outpatient clinics essentially care for vulnerable populations [11–13]. Such psychosocial complexity may prepare residents to face and cope with health disparities, but can also overwhelm them, while they are already struggling to learn the fundamentals of outpatient practice [3].

Second, the experience of continuity of care is often lacking in academic centres, where residents rotate usually for a year or less. One year is a short period of time to build up relationships with patients, to evaluate the impact of medical decisions and prescriptions on the course of patients’ illnesses, and to discover different aspects of team work in chronic disease management. In addition, continuity of care appears to be particularly important for more vulnerable patients [14].

Third, during a training year in academic settings, residents may often be exclusively assigned to care for a specific type of patient population, such as elderly people, undocumented migrants, prisoners or patients with substance abuse, because it facilitates the organisation of care and team work within a unit. This may be a matter of concern, since residents’ patient case mix may not be representative of patient populations that residents will care for once in private practice [15].

For these reasons, the Division of Primary Care Medicine of the Geneva University Hospitals decided in 2007 upon a reform of its postgraduate curriculum in outpatient general internal medicine that was implemented in October 2008.

In this paper, we report the development, implementation and evaluation of a postgraduate curriculum designed to respond to residents’ training needs in terms of patient case mix, variety of relevant clinical activities and continuity of care, while allowing the division to continue to appropriately fulfill its commitment to vulnerable patients.

The Division of primary care medicine is part of the Department of Community Medicine, Primary Care and Emergency Medicine at the University Hospitals of Geneva, Switzerland. It is spread out over 7 geographically distinct medical sites over the city (fig. 1). However, most clinical activities are conducted in the main hospital building (fig. 1). Its mission consists in delivering medical care, in providing pre- and post-graduate training, and in conducting research in community-based clinics in Geneva, a canton of 450000 inhabitants. Each year, it provides 15000 scheduled medical consultations and 13000 consultations at its medical and surgical walk-in emergency clinics. It also trains 38 full time residents in ambulatory care. Its patient population includes the general population of Geneva and, more specifically, vulnerable populations such as asylum seekers, undocumented migrants, patients without insurance coverage, prisoners, frail elderly people bound to their homes, and patients with substance abuse. A previous study showed that 50% of the patients attending the primary care clinic were immigrants and that 40% did not speak French [16].

Figure 1

Medical sites and units belonging to the Division of Primary Care Medicine.

Figure 2

Model of a week organisation before and after the implementation of the new curriculum.

Before 2008, many residents would typically work during a week for 4 days in a continuity clinic and one day in the emergency walk-in clinic during one year. Others would work during the whole week in a specific unit of the division, providing care to elderly people at home, prisoners or patients with substance abuse during the same year (fig. 2). As a result, some residents were exposed to a very specific profile of patients (e.g., young males in prison, middle-aged South American women in the clinic for undocumented patients, old and frail elderly in the elderly day hospital), while others were not experiencing continuity of care over an entire year. In parallel, nurses, dieticians and social workers would see patients at residents’ request but, in some units, there were no regular interprofessional sessions planned to exchange information about patients and work progress.

The planning and development of the new curriculum was guided by two principles: continuity of care and exposure to a wide variety of patients and clinical activities.

The following steps were undertaken:

Using a literature review [17–22], a group of senior residents from different clinical units defined, inside three dimensions (patient, self and environment), core competencies to be acquired during the two years of residency training in ambulatory care. They are summarised in table 1 and more detailed information on general and specific learning objectives for each clinical unit can be found on the primary care division’s website [23]. These competencies and learning objectives were then reviewed by a panel of academic and non-academic general practitioners, in order to organize the content of the structured and non-structured learning activities of the curriculum. Structured training includes 5 weekly training hours required by the Swiss society of physicians (FMH) and non-structured learning activities refer to formal and informal supervision provided during clinical activities.

Resident supervisions, implemented in 2007, were strengthened and consisted in: (1) 1 hour of supervision per half-week (protected time in the schedule) with the same supervisor, to discuss the clinical cases of the day; (2) direct observation of one consultation per month by the supervisor followed by 10 minutes of feedback; and (3) structured review of 5 medical files per month by the supervisor, with the use of a 14 item-checklist focusing on the following aspects: history taking and physical exam (adequate link between patient’s symptoms and the problem list), appropriateness of diagnostic investigations, treatment and follow-up, appropriateness of preventive interventions, appropriateness of specialist referrals, documentation of allergy and medication intolerance, documentation of missed appointment, phone calls, etc…

In parallel, a mixed group of senior residents and residents regularly met during 6 months in 2007 to identify and prioritize clinical activities taking place in the division of primary care medicine, according to the clinical fields in which residents were expected to become skilled and professionally competent. The clinical activities taking place in the following settings were considered to be compulsory: continuity clinics, surgical and medical walk-in emergencies, home visits to elderly people, and substance abuse consultations. Clinics for prisoners, health service for hospital employees, and the short-stay unit for investigations and treatments were considered as optional rotations.

Subsequently, learning objectives were elaborated by the senior residents working in the different care units and reviewed by a committee for relevance and clarity, before being disseminated.

In the new curriculum, the training week was divided into two blocks: 2½ days dedicated to the same continuity clinic for 2 years and 2½ days devoted to 6–12 months rotation in different clinical units, such as walk-in medical and surgical emergency clinics, clinics for prisoners, home visits for the elderly. This organisation aimed at conciliating both continuity of care for chronic patients and exposure to a wider spectrum of clinical activities for residents (fig. 2). Care for patients with substance abuse were integrated into follow-up consultations with bi-monthly supervision, preceded by a two half-day crash course on substance abuse for residents, given by addiction specialists in the field. Four hours of structured teaching activities were concentrated in one half day (Wednesday morning) to allow all residents working in different geographical areas to attend them.

Because residents spent less time in the same unit (2½ days instead of 4 to 5 days a week), we decided to reinforce team work in order to maintain quality of care and communication through 3 changes: 1) creation of small clinical sub-units or teams composed of 1 attending physician, 2 part-time senior residents, 6 to 8 residents and a secretary in all units; 2) maintenance of the attending physician and senior residents in the same unit over an entire year; 3) bi-monthly meetings with other health professionals working on the same team (nurses, dietician, social workers and administrative staff).

| Table 1: List of professional core competencies, resident learning outcomes and training activities of the new curriculum | |||||||

| Dimension | Professional competencies and learning outcomes After completion of the two year educational programme, the resident will be able to: | % Structured training | Structure training | Unstructured training | Inter- professional meetings | External training | Mentorship |

| Patient | Perform a complete and appropriate patient evaluation | 75% | X | ||||

| Apply effective and appropriate preventive and therapeutic interventions | X | X | |||||

| Document relevant elements of care in the medical file | X | ||||||

| Establish a trustful relationship and partnership with the patient | X | X | |||||

| Self | Care of one’s self | 10% | X | X | X | ||

| Acquire, maintain and improve professional competences | X | X | X | ||||

| Establish an career or personal development plan | X | X | |||||

| Develop critical thinking and use it in clinical decision making | X | X | |||||

| Demonstrate commitment to patients, profession and society by a respectful and ethical behavior | X | X | X | ||||

| Demonstrate commitment to patients, profession and society by taking part into the professional self-regulations | X | ||||||

| Environment | To collaborate with health professionals and other workers | 15% | X | X | X | ||

| Use resources in an appropriate manner | X | X | X | ||||

| Orient the patient in the socio-sanitary environment in an appropriate way | X | X | X | ||||

| Favour prevention and health promotion on both individual and community levels | X | X | X | ||||

| Inform oneself about medical professional politics | X | ||||||

| Participate to the development and maintenance of a quality system | X | ||||||

| Facilitate medical students’ and other health professionals’ learning | |||||||

| Contribute to creation, diffusion, application and use of new medical knowledge and practice | X | ||||||

The curriculum was implemented on 1 October 2008, at the start of a new academic year.

One senior attending physician and a secretary were designated to take responsibility for the overall management aspects of the curriculum. It consisted of:

1 Regularly collecting, documenting and validating residents’ planned schedules, activities and absences on an overview table (work done by the secretary). We used an Excel table hosted on a common server to manage and make this information accessible in a registry by all computers from all sites of the division.

2 Re-allocating residents in case of unplanned absences and ensuring balance in residents’ reallocation between the different clinical units.

During the first 3-month implementation, bi-monthly meetings were organised between the attending physicians in charge of the units to discuss difficulties linked to the new curriculum and to find solutions. It essentially focused on re-scheduling interprofessional meetings and ensuring that all residents received the same information and training sessions specific to each unit.

At three months, the Head of the Division organised a half-day brainstorming meeting on the new curriculum, involving all medical, nursing and administrative collaborators. According to the results of a written survey described below, three discussion groups worked on the following problematic issues: 1) difficulties in transmitting information and in patient follow-up over the week between resident pairs; 2) interprofessional collaboration; 3) dilution of specific knowledge required in some units (for example, knowledge of administrative procedures related to migrants (e.g., asylum seekers or undocumented migrants). Several remedial strategies were found and adopted during the following 6 months: 1) transmission of information between resident pairs: allocation of the first 30 minutes of the first working day of the half-week (Monday and Thursday) to residents’ contact by phone or e-mail with their work partner about patient follow-ups; overlapping of residents’ working days by senior residents’ working days in order to ensure better follow-up of some complex or unstable patients; 2) more frequent integration of other health professionals in structured training and teaching activities; and 3) dedication of one hour/month of structured training time to specific aspects related to the units, in order to gain more specific information/knowledge/skills. In addition, as all groups highlighted the importance of a common computerised patient file to improve communication, we accelerated the development of an electronic medical record.

The content of the structured and non-structured training activities was organised according to the core competencies and learning objectives defined above (table 1). During the half-day of structured training, topics of learning activities were distributed over the year in the following way: 75% of structured learning activities were dedicated to patient care and focused on clinical issues (e.g., urinary tract infection, arterial hypertension), 10% to one self (e.g., self-awareness seminars, journal clubs and case presentation prepared by residents) and 15% to patient care and environment (e.g., workshop on social insurances organised by social workers). More detailed information is accessible on the primary care division’s website [23].

Three and 24 months after its implementation on 1 October 2008, satisfaction with the new curriculum was evaluated through postal and electronic surveys among all residents working in the division, independently from the time they entered the new curriculum, and among senior residents, nurses and administrative staff. The survey was developed to assess the impact of the new curriculum on quality of patient care, team work, and residents’ learning, consisted of questionnaire items developed using a Delphi-type of process. A sample of residents, senior residents, nurses and administrative staff were asked to make suggestions about the topics/themes to survey. A first survey draft was then sent back to them and content and formulations were modified according to their remarks. The final questionnaire included 10 items using a 5-point Likert scale (not agree (1) to fully agree (5). We focus here on the 4 most relevant items dealing with the major curriculum changes: global satisfaction, amount of learning, difficulties with patient follow-up over the week, impact of interprofessional meetings on patient care, and team work. They included the following questions: 1) I am globally satisfied with the curriculum organisation which allows residents to follow patients during two years and to increase their clinical experience by rotating in different units of the division; 2) The presence of residents in the unit during half a week is sufficient for patient follow-up; 3) Interprofessional meetings improve the quality of patient care; 4) Interprofessional meetings increase team building and cohesion. Two additional questions were added for residents: 1a) the new curriculum increases my learning 1b) to work on two different sites creates more benefits than difficulties.

To assess whether the quality of postgraduate training changed after implementation of the curriculum, we also used data from the yearly self-administered surveys performed by the Swiss society of physicians (FMH) among residents, which evaluate the quality of the postgraduate training centres. We could not compare our results with other centres involved in ambulatory care training, since the FMH does not give access to results of other institutions individually. Finally, we reviewed the division’s yearly planning documents between 2006 and 2010 to identify the proportion of residents who suffered from burnout, experienced a major deviation from their initial plan due to a pregnancy or a career change, as well as the number of weeks during which a replacement was required to overcome these difficulties.

The new 2-year postgraduate curriculum was developed to ensure that residents would be exposed to a sufficiently broad spectrum of clinical activities and to an appropriate case mix of patients, while facilitating continuity of care on a longer follow-up period for chronic patients. It required redefining core competences to be acquired, reorganising the residents’ working week in two different clinical activities and strengthening interprofessional collaboration to ensure patient follow-up and communication. Despite management difficulties linked to these entangled activities and some resistance to change from some professional groups, the new curriculum seemed to meet some of its educational objectives. Most residents who responded to the survey expressed their satisfaction with the new curriculum, particularly because of the wide variety of learning experiences. Combination of acute and longitudinal clinical activities where especially appreciated. Residents acknowledged that working in two different sites provided a positive balance. Interprofessional meetings were highly valued by all collaborators. However residents, nursing and administrative staff reported difficulties in patient follow-up due to decreased time spent by residents in each clinical unit.

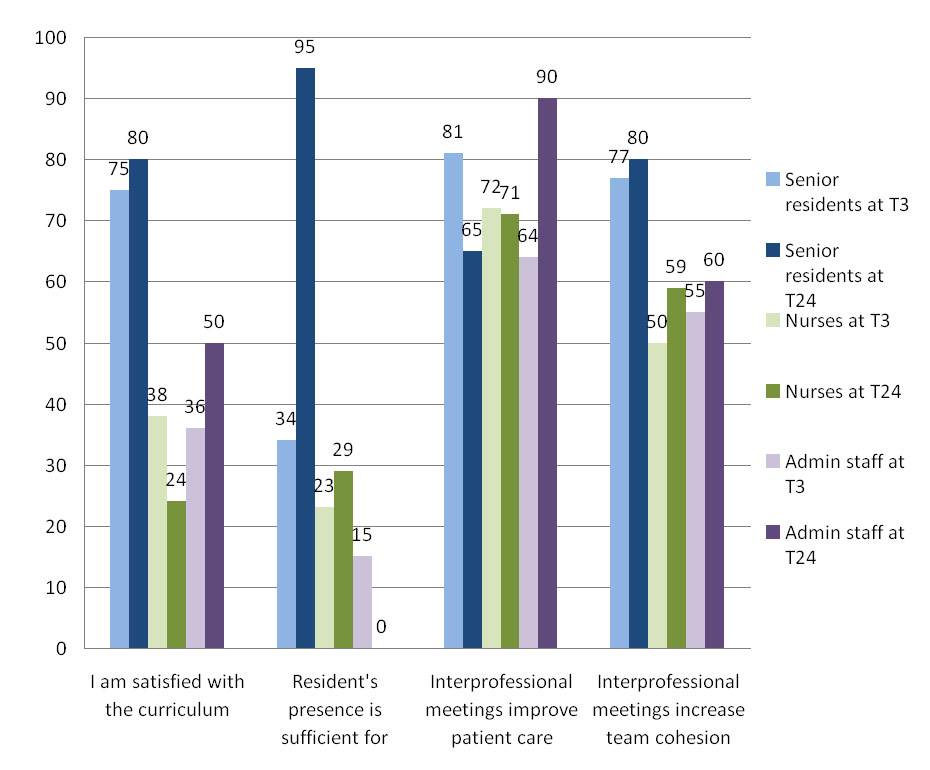

Figure 5

Evaluation of the new curriculum at 3 (T3) and 24 months (T24) by senior residents, nurses and administrative staff (expressed in %).

Response rates: senior residents: n = 19 (43%) at T3 and n = 20 (44%) at T24; nurses: n = 28 (47%) at T3 and n = 17 (27%) at T24, administrative staff: n = 26 (87%) at T3 and n = 10 (50%) at T24.

Our results are in accordance with other data showing that training in ambulatory care was considered to be optimal and successful when residents were exposed to an adequate number and variety of patients [24], but also when there is a good balance between longitudinal and acute care. Continuity of care was highly valued by the residents who stayed in the division two years. Numerous studies show that continuity of care has a positive impact with increased satisfaction of both patients and physicians and decreased patients’ use of emergency rooms [5, 25, 26]. Extending the training period to two years offers residents more opportunities to develop and consolidate their competencies in ambulatory medicine and provides longer continuity of care and interpersonal relationships with patients, which is particularly important for vulnerable populations [14].

Residents, nursing and administrative staff reported difficulties in patient follow-up with the new curriculum. Several improvements were made during the following years to ensure that residents would be easily reachable for questions regarding patients, while working at another site, and that transmissions and hands-off procedures would be secured by setting specific time slots in the residents’ weekly schedules.

All valued interprofessional meetings, especially for patient follow-up and, to a lesser degree, for team building. Such meetings may contribute to train professionals in how to function as interprofessional health care teams. Given the current shift from inpatient to outpatient care and the emergence of disease management programmes, primary care institutions have a new important educational role to play in providing opportunities for different health professionals to learn from and about each other and to prepare them to work in teams [27]. Interprofessional teamwork and collaboration are strongly encouraged by accrediting bodies in medicine, nursing and social work, in Switzerland and elsewhere [28]. They are seen as essential strategies to improve health care processes and outcomes [29, 30]; however, they require good communication skills and strong information and communication technologies (ICT). A shared electronic medical record by all health professionals, wished by all collaborators, is now being implemented in our division and will become a complementary tool to improve transmission of information and follow-up of patients over the week.

The complexity of the new organisation required important management and coordination resources. Use of more sophisticated electronic human resources software than simple Excel tables may facilitate the management of complex schedules, activities and absences. They may help to both take into account and to conciliate unit-specific and institutional priorities and constraints. In addition, transferring the organisational challenges of such curricula to a skilled project manager may be highly desirable and could help decrease the amount of time dedicated by senior physicians to purely administrative management of human resources.

Successful implementation of a new organisation in health care or education depends on three core elements – the level and nature of the evidence, the context of environment into which the change is to be placed and the methods or ways in which the process is facilitated [31]. The need for more diverse and enlarged learning activities was based on medical experts and research-based literature [3, 5, 15] .The context, the division of primary care, is a diversified organisation composed of several care units geographically spread over the city, as shown in figure 1, and which tended to work in a rather autonomous way [32]. Such organisation pattern did not favour the curriculum’s development and implementation, because it forced specific units to adapt their functioning and priorities to the new educational challenges. However, facilitation processes, such as a strong leadership of the head of the division, active involvement of senior residents, acting as bridges between units’ specificities and the overall educational project requirements, as well as the multiple preparatory interprofessional meetings, helped to make the project implementable. The implemented project led to the desired diversification of clinical activities and formalisation of residents’ professional competencies.

There were several limitations in the design, implementation and evaluation of the curriculum. First, the yield of the evaluation survey was limited by a rather low response rate and we cannot exclude a bias by respondents being either very dissatisfied or very satisfied with the new curriculum. However, response rates to the national survey performed by the Swiss society of physicians were equally low before and during the implementation of the curriculum; although we have no explanation for it, it would be surprising that reasons for not answering surveys would have differed between years. Second, patients, as opposed to residents, senior residents and private general practitioners, were not involved in designing or evaluating the curriculum, despite the fact that they were directly concerned by the changes introduced. We do not know in which way they were affected by it. Since our division was not yet included in routine patient satisfaction surveys of the Geneva University Hospitals, we could not document any change in patient satisfaction regarding their care. However, there was no report of patients quitting, while the number of patients being cared for in our division increased over the last two years. Third, we did not assess residents’ performance in an objective and summative way and, therefore, were unable to know whether their performance improved over time thanks to the curriculum change. Such assessments are highly desirable and will be soon required by the Swiss Federation of Physicians (FMH) for board certification in general internal medicine.

In conclusion, the new two-year postgraduate curriculum in outpatient general internal medicine was developed to better prepare residents to provide preventive, acute, and chronic care to the general population, by increasing diversity in learning activities, patient case mix, and continuity of care over a longer period of training. The implementation of a new curriculum for post graduate residency training appeared to be satisfying. It gave us the opportunity to revise and formalise competences to acquire, redesign the training activities accordingly, identify compulsory clinical activities and reinforce interprofessional collaboration. It also gave us insights into challenges which have to be addressed when disseminating new training schedules and activities: it needs local champions, makes management of human resources more complex and requires the skills of a real project manager. It also requires additional ICT support to optimise interprofessional team care and, finally, it makes patient care more challenging. The next step is to define and implement an assessment system in order to monitor residents’ progress and professional performance along future organisational changes.

1 Perkoff GT. Teaching clinical medicine in the ambulatory setting. An idea whose time may have finally come. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(1):27–31.

2 Wiest FC, Ferris TG, Gokhale M, Campbell EG, Weissman JS, Blumenthal D. Preparedness of internal medicine and family practice residents for treating common conditions. JAMA. 2002;288(20):2609–14.

3 Holmboe ES, Bowen JL, Green M, Gregg J, DiFrancesco L, Reynolds E, et al. Reforming internal medicine residency training. A report from the Society of General Internal Medicine’s task force for residency reform. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1165–72.

4 Junod AF. Will there be room for the teaching of internal medicine in a university hospital? Swiss Med Wkly. 2002;132(1-2):4–6.

5 Bowen JL, Salerno SM, Chamberlain JK, Eckstrom E, Chen HL, Brandenburg S. Changing habits of practice. Transforming internal medicine residency education in ambulatory settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(12):1181–7.

6 Fédération des Médecins Suisses. Programme de formation postgraduée du 1er janvier 2011: spécialiste en médecine interne générale 2011 [20th June 2011]. Available from: http://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf5/aim_wbp_f.pdf.

7 Brinkley B, Viret JD. Assistanat au cabinet médical: le modèle genevois. Primary Care. 2001;1:454–5.

8 Feller S. L’assistanat au cabinet médical: «... la période la plus instructive de ma formation!». Bulletin des médecins suisses. 2005;86(39):2237–43.

9 Conférence suisse des directrices et des directeurs cantonaux de la santé. Rapport final: financement «formation postgrade spécifique»: http://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf5/aim_wbp_f.pdf.; 2006 [20th June 2011].

10 Gilchrist V, Miller RS, Gillanders WR, Scheid DC, Logue EE, Iverson DC, et al. Does family practice at residency teaching sites reflect community practice? J Fam Pract. 1993;37(6):555–63.

11 Marti C WH. Inégalités sociales et accès aux soins: conséquences de la révision LAMal (article 64A). Rev Med Suisse. 2006;2:2503–7.

12 Wolff H, Besson M, Holst M, Induni E, Stalder H. Inégalités sociales et santé: l’expérience de l’Unité mobile de soins communautaires à Genève Rev Med Suisse. 2005;1:2218–22.

13 Bodenmann P, Althaus F, Carbajal M, Marguerat I, Kohler D, Jackson Y, et al. «La enfermedad del millionario» («la maladie du millionnaire») Prise en charge transculturelle d’une patiente équatorienne. Forum Med Suisse. 2010;10(6):102–7.

14 Nutting PA, Goodwin MA, Flocke SA, Zyzanski SJ, Stange KC. Continuity of primary care: to whom does it matter and when? Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(3):149–55.

15 Irby DM. Teaching and learning in ambulatory care settings: a thematic review of the literature. Acad Med. 1995;70(10):898–931.

16 Bischoff A, Tonnerre C, Loutan L, Stalder H. Language difficulties in an outpatient clinic in Switzerland. Soz Praventivmed. 1999;44(6):283–7.

17 Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada. The CanMEDS 2005 Physician Competency Framework 2011 [20th June 2011]. Available from: http://rcpsc.medical.org/canmeds/CanMEDS2005/index.php.

18 The European Academy of Teachers in General Practic and Family Medicine. The European definition of general practice/family medicine 2005. Available from: http://www.euract.org/.

19 Working group under a mandate of the Joint Commission of the Swiss Medical Schools. Swiss Catalogue of Learning Objectives for Undergraduate Medical Training 2008 [20th June 2011]. Available from: http://sclo.smifk.ch/downloads/sclo_2008.pdf.

20 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Common program requirements: General competencies 2007 [20th June 2011]. Available from: http://www.acgme.org/acWebsite/home/home.asp.

21 Pruitt SD, Epping-Jordan JE. Preparing the 21st century global healthcare workforce. BMJ. 2005;330(7492):637–9.

22 Hays RB, Davies HA, Beard JD, Caldon LJ, Farmer EA, Finucane PM, et al. Selecting performance assessment methods for experienced physicians. Medical education. 2002;36(10):910–7.

23 Primary Care Division GUH. Training, supervision and evaluation: http://premier-recours.hug-ge.ch/enseignement/PresentationSMPR_Objectifs_Progr_didactique_Supervision_Mentorat_Recherche_2010-11x.pdf; page 13-19 and 20-33; 2008 [4th March 2012].

24 Schultz KW, Kirby J, Delva D, Godwin M, Verma S, Birtwhistle R, et al. Medical students’ and residents’ preferred site characteristics and preceptor behaviours for learning in the ambulatory setting: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2004;4:12.

25 Ogrinc G, Mutha S, Irby DM. Evidence for longitudinal ambulatory care rotations: a review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(7):688–93.

26 Saultz JW, Albedaiwi W. Interpersonal continuity of care and patient satisfaction: a critical review. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(5):445–51.

27 Price D, Howard M, Hilts L, Dolovich L, McCarthy L, Walsh AE, et al. Interprofessional education in academic family medicine teaching units: a functional program and culture. Can Fam Physician. 2009;55(9):901–1 e1-5.

28 Group de Travail de l'Association Suisse des Sciences Médicales. Les futures profils professionnels des médecins et des infirmiers dans la pratique ambulatoire et clinique. Bulletin des médecins suisses. 2007;88(46):1942–52.

29 Zwarenstein M, Goldman J, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration: effects of practice-based interventions on professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD000072.

30 Coleman MT, Roberts K, Wulff D, van Zyl R, Newton K. Interprofessional ambulatory primary care practice-based educational program. J Interprof Care. 2008;22(1):69–84.

31 Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Quality in health care: QHC. 1998;7(3):149–58.

32 Mintzberg H. Patterns in strategy formation. Management Science. 1978;24:934–48.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.