Figure 1

Steps the patient indicated before he decided to come to the emergency department?

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13565

A pilot survey of 200 consecutive patients from Switzerland

Although Switzerland has an excellent general practitioner (GP) system, there is a growing trend for patients to go directly to a local emergency department [1, 2]. This is particularly the case for “out-of-hours” emergencies and in urban areas [3]. A study from Bern showed that up to 75% of all out-of-hours patients visiting the emergency department (ED) had no GP [5]. There are a variety of reasons for this trend, including the unrestricted opening hours of emergency departments, their general accessibility by public transport or a subjective feeling of the urgency of the illness/injury [4]. However, many patients feel that there are other barriers hindering their access to primary care. These include language barriers or natural shame, which prevents them from being able or wanting to describe their problems to the GP and which leads them to prefer the anonymity of the emergency department [5].

Figure 1

Steps the patient indicated before he decided to come to the emergency department?

But an uncontrolled patient mixture of non-urgent walk-in patients and acute emergencies in the same emergency department inevitably makes it more difficult to provide genuine emergencies with rapid treatment, leading to deterioration in the quality of emergency services, together with higher overall costs [6]. This can lead to a crisis in emergency department medical care, with overcrowding, overboarding and delays in care [7].

To our knowledge, this is the first study from Switzerland which surveys and discusses the motives of walk-in patients in visiting a university emergency department during GP office hours.

A series of consecutive walk-in patients were analysed. Intoxicated patients or patients who could not understand German were excluded. Data acquisition was performed during general practitioners’ office hours. To avoid selection bias, we performed the survey on 31 randomly chosen days, between 11 July 2011 and 31 August 2011, except weekends and Thursday afternoons, when GP offices in Bern are closed. The patients were interviewed using a paper based, self-administered questionnaire (pdf), which was distributed by a medical student not involved in the medical treatment. The questionnaire was based on a previously published questionnaire, which was adapted to the needs of our survey [9]. The adaptation was performed using expert opinion (UM, AB, AKE). The questionnaire consisted of 15 questions: 7 on demographic characteristics, 3 on the reason for visiting the emergency department, 2 on the patient’s satisfaction and 3 on how patients define a medical emergency situation. Descriptive statistics were performed. We did not monitor a severity index in the included or in the excluded patients. This means that the urge to visit the emergency department was not quantified. Thus the study focused on the decision process when patients decide to visit our department

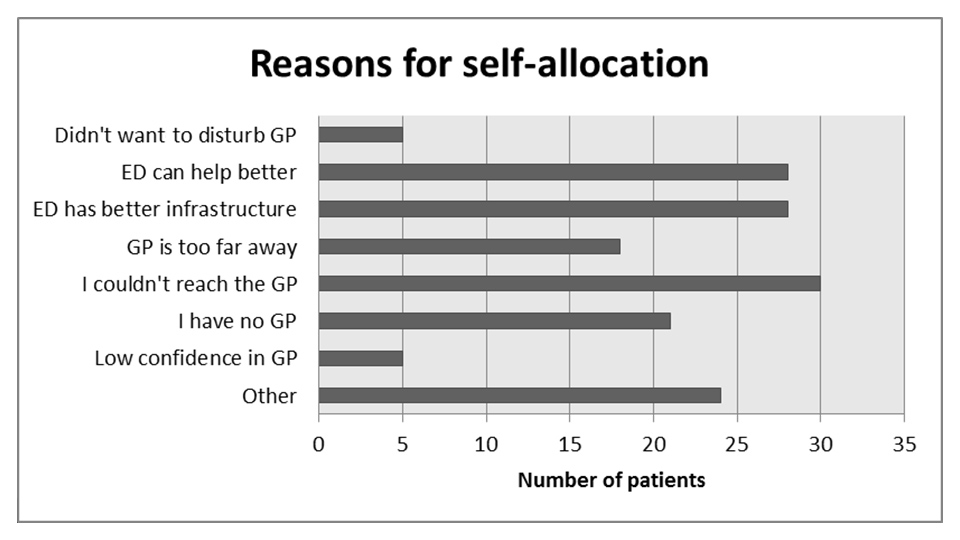

Figure 2

Why did I choose to visit a hospital ED instead of a GP?

No ethics approval was necessary for this kind of survey.

200 patients (males = 129) were interviewed during the study period. Their mean age was 35.5 years (range 15–83). 65% of the patients (n = 129) were male and 70% (n = 136) were of Swiss origin. The majority of walk-in patients interviewed – 82% (n = 165) – were registered with a GP.

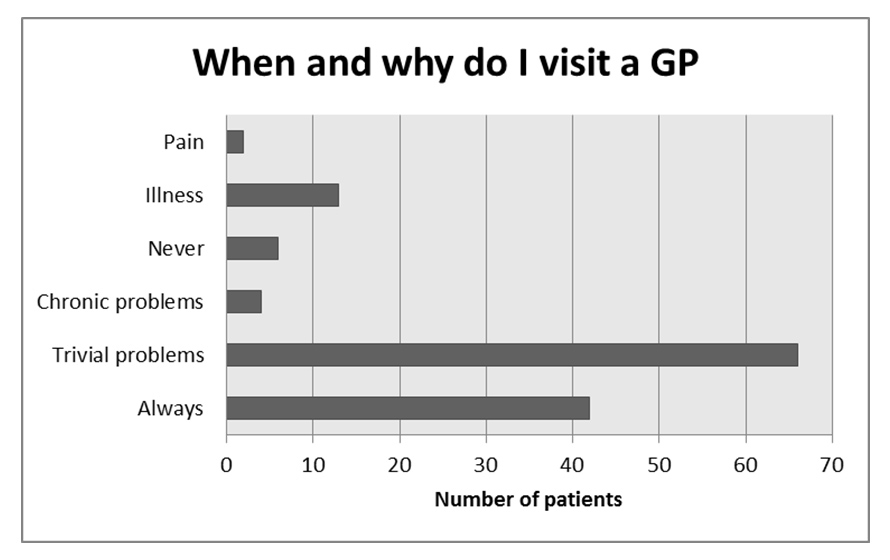

Figure 3

When and why do I visit a GP?

There was no difference between Swiss and non-Swiss patients with respect to the affiliation to a GP; 83% of Swiss patients (n = 113) and 80% of non-Swiss walk-in patients (n = 51) were registered.

With respect to employment status, 132 (66%) of all patients were fully or part time employed, 10 (5%) were unemployed, 28 (14%) in education, 9 (4%) had a disabled person pension fund and 20 (10%) patients were retired. 53 (27%) patients had received higher education (University), 110 (55%) patients intermediate level education (professional training), 30 (15%) basic education and 6 (3%) no education.

When asked about the circumstances of admission and subjective drivers to visit our emergency department, 39% (n = 61) patients reported greater confidence in the hospital emergency department (fig. 1 and 2).

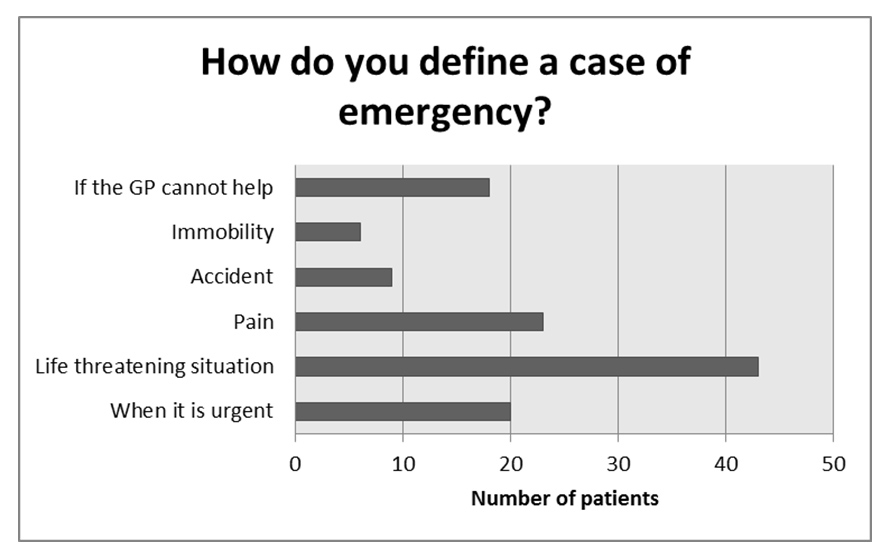

When asked “When and why do I visit a GP?”, most of them either stated that this was for trivial problems (54%, n = 66) or always (35%, n = 42) and the majority defined an emergency as either a condition requiring rapid attention or a life threatening situation (53%, n = 63). (fig. 3 and 4)

With nearly all Swiss hospitals running at a high number of ED visits, it has become more difficult to see patients within a specific period of time and in all necessary detail. This seems especially true for patients who not require the full attention of the ED staff, as do stroke or trauma patients, and who compete for a limited number of doctors and nurses. With no other place to send less seriously ill or injured patients in need of attention, EDs must hold these patients for increasingly greater periods of time until a physician or a nurse is available to see them. These patients, commonly referred to as “walk-in patients”, require substantial care and consume the limited resources of the ED. Such walk-in patients, who mingle with higher triaged patients on the same floor, essentially shrink the capacity of the ED and compromise its ability to provide timely care for incoming outpatient cases as well as acute patients who are still waiting to be seen. Although, no high level evidence exists that such walk-in patients increase the risk of medical errors, we suggest physical and medical separation of walk-in patients from the other patients during triage. In this way, we acknowledge the wish of the patient to be seen in hospital and provide them with primary care at the same time. Some hospitals in Switzerland have acknowledged this by creating partnership programmes with local GP’s or by outsourcing the “walk-in business” to ED integrated primary care provider groups.

Figure 4

How do you define an emergency?

The increasing urbanisation in Switzerland, the increasing mobility of the population with the high proportion of commuters, as well as the new demands on the opening hours for service suppliers of all types, do not seem to stop at the doors of emergency departments or general practices [9].

It is interesting that 51 (25%) of the patients first called the GP, who then advised them to go directly to the ED without seeing them and about 30 patients (15%) failed to reach their GP during office hours. There are many possible reasons for this and a further study should look closer to this point.

Moreover, increasing numbers of patients – both Swiss and foreigners – have no GP at all – as an earlier study has shown [4]. Most of the patients interviewed were socially integrated, had a job and even a GP, if only theoretically. Our survey though might be of limited reliability, due to the small numbers of patients. Anyhow our study is another small piece of the puzzle to help us to understand why people in medical emergencies prefer to consult rather a hospital than their own GP. Our study supports the impression from current literature that there is a growing demand for hospital-based emergency medicine. Some emergency patients seem to feel that only hospital EDs can provide them with adequate emergency treatment, but the underlying sociological reasons for this remain unclear. We can only speculate about the reasons for this. Is it a question of supply and demand? There are eight emergency departments in our city alone which offer their services all around the clock. Only a future large study on the drivers and barriers to emergency care in Switzerland can provide additional answers.

The increase in the numbers of walk-in patients is one of the main reasons that many emergency departments in Switzerland and other countries are suffering from bottlenecks in their capacity – with unfortunate consequences. Hospital staff are frustrated, patients complain about long waiting times, ambulances must be diverted, higher costs arise and the reliability and quality of health care and treatment may be at risk. Although most primary care physicians provide their patients with a high standard of care in any kind of emergencies, we speculate that in future more walk-in patients will turn their backs on their GPs and rely on hospital ED’s in case of medical emergencies [10].

What is important is that GPs, hospitals, politicians and insurance companies should work together to solve these problems and to guarantee cost-effective and high quality health care for emergency patients within and outside hospitals.

1 «Notfälle direkt ins Spital? Ein wichtiger Mechanismus der Kostenlawine». Hoby G. Standpunkte • Schweiz Ärztezeitung. 2005;86(27):1694–5.

2 Bagatellunfall auf der Notfallpforte eines Universitätsspitals. Müller U. PrimaryCare. 2005;5(17):39.

3 Out-of-hours demand in primary care: frequency, mode of contact and reasons for encounter in Switzerland. Huber CA, Rosemann T, Zoller M, Eichler K, Senn O. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011;17(1):174–9.

4 Interdisciplinary emergency response units: he who comes too late is punished by life and or by the hospital management! Exadaktylos AK, Zimmermann H. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2009;134(23):1236–7.

5 Referral practice among Swiss and non-Swiss walk-in patients in an urban surgical emergency department. Clément N, Businger A, Martinolli L, Zimmermann H, Exadaktylos AK. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010 Oct 21.

6 Emergency medicine and acute care surgery: a modern “Hansel and Gretel” fairytale? Exadaktylos AK, Velmahos GC. Emerg Med J. 2008;25(6):321–2.

7 Strategic emergency department design: An approach to capacity planning in healthcare provision in overcrowded emergency rooms. Exadaktylos AK, Evangelopoulos DS, Wullschleger M, Bürki L, Zimmermann H. J Trauma Manag Outcomes. 2008;2(1):11.

8 Motivation and relevance of emergency room visits among immigrants and patients of Danish origin. Marie Norredam, Anna Mygind, Anette Sonne Nielsen, Jens Bagger, Allan Krasnik. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(5):497–502. Epub 2007 Jan 27.

9 Cost reduction strategies for emergency services: insurance role, practice changes and patients accountability. Simonet D.Health Care Anal. 2009;17(3):1–19. Epub 2008 Feb 28. Review.

10 Management and outcome of severely elevated blood pressure in primary care: A prospective observational study. Merlo C, Bally K, Martina B, Tschudi P, Zeller A. Swiss Med Wkly. 2012;142:0.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.