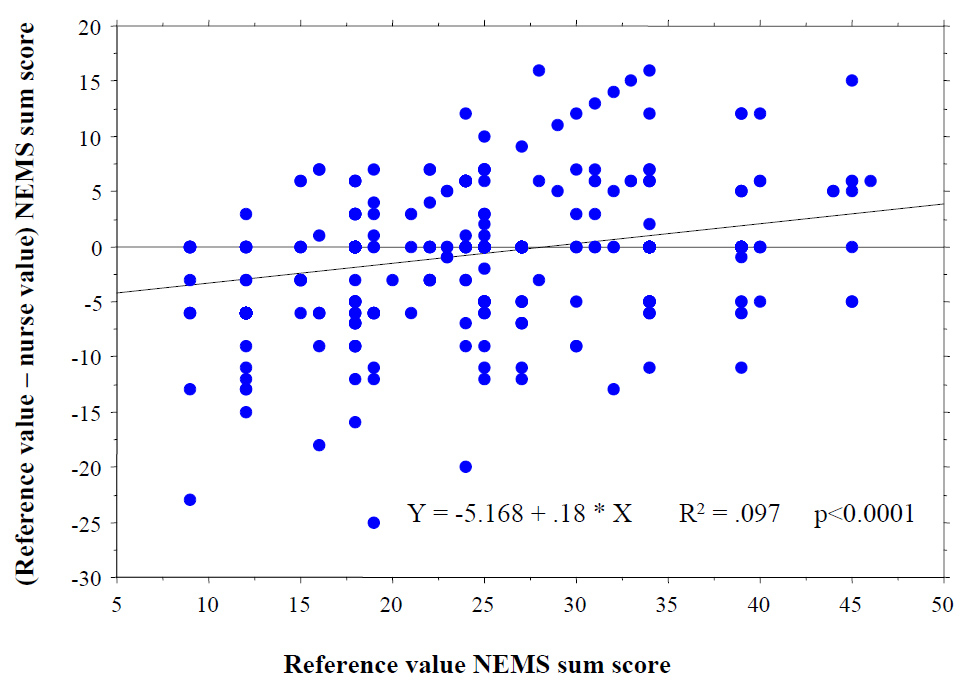

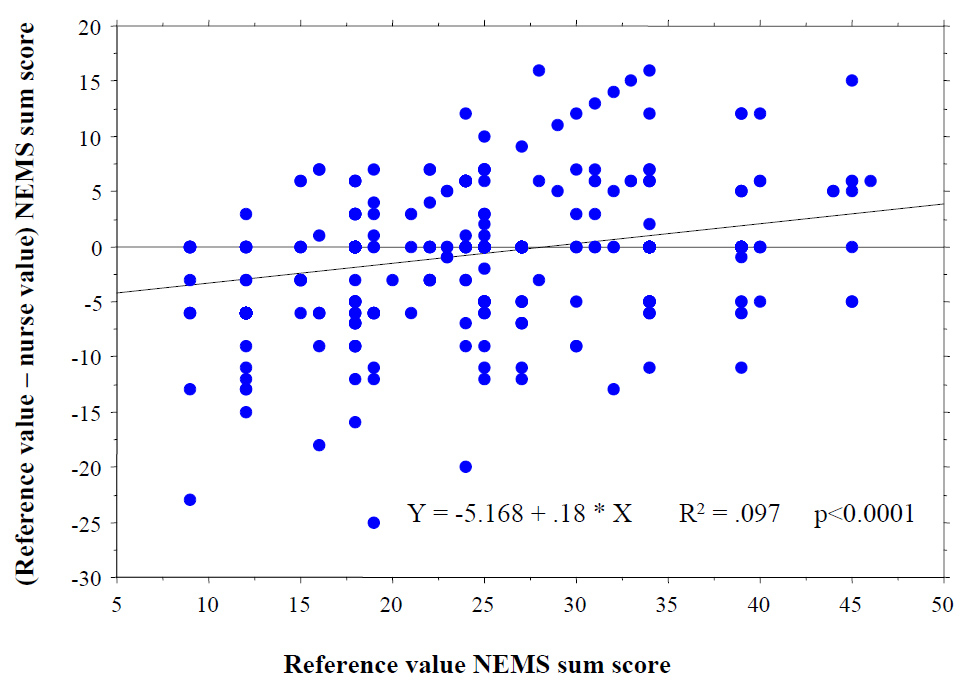

Figure 1

Linear regression between the difference (reference value – nurse value) of the NEMS sum-score and the mean NEMS sum-score [(reference value + nurse value) x 0.5].

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13555

Adequate nurse staffing is a prerogative for good quality of care for both the general ward [1] and the intensive care unit (ICU) [2]. Moreover, burnout and job dissatisfaction among nurses are reported to be inversely associated with low patient-to-nurse ratios [3]. On the other hand, manpower use is a major contributor to costs [4], and scarce financial resources always render sufficient allocation of nurses more difficult. Consequently, suitable therapeutic indexes have been developed to quantify, evaluate and allocate nursing workload at the ICU level [5–7]. The nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS) [8] derives from a simplified form of the therapeutic intervention scoring system (TISS-28) [7] and is now frequently used for management purposes and multicentre ICU studies. These workload indicators have also become, in addition to the simplified acute physiology score II (SAPS II) [9], a key component in defining the degree of hospital reimbursement in Germany [10]. In Switzerland, an analogous procedure – SwissDRG – was introduced at the beginning of 2012 [11, 12]. Moreover, Swiss ICUs have a long tradition concerning quality issues [13] and the NEMS is one of the most important components among the mandatory process indicators that must be collected.

Considering the various implications, accuracy in the assessment of NEMS scores is of the utmost importance. Scoring systems are performant only when they furnish credible results, the latter depending principally on accurate data collection, appropriate know-how and correct application of definitions among the users. Accuracy and reliability of NEMS has been poorly studied, with the exception of a formal analysis of data accuracy in the original publication [8]. However, these results refer to a well defined study setting with specifically trained observers, and to the best of our knowledge no study has so far assessed the accuracy of nurse registered NEMS scores in real life.

The aim of our study was 1) to assess the accuracy of nurse registered NEMS scores in real life, 2) to recognise error-prone variables and 3) to design an appropriate improvement intervention.

This is a retrospective multicentric study conducted within the Department of Intensive Care Medicine of the Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale, Ticino, Switzerland. Our department groups the mixed ICUs from 4 regional teaching hospitals (Bellinzona, Locarno, Lugano, Mendrisio), has a total of 34 beds and cares for about 3,200 adult patients per year. Among the 159 nurses (with varying degrees of occupation), 70% are critical-care registered, whereas the rest are registered nurses with ongoing specific training. Nurse-to-patient ratio is usually 1:1.5.

In our ICUs the NEMS score is manually assessed by the nurses. There are three shifts per day and at the end of each shift the nurse responsible for the respective patient manually scores the past workload according to the original definitions [8]. Along with physiologic data and laboratory findings all medications and therapeutic procedures are consecutively documented by nurses on the daily patient survey charts, from which they are ultimately retrieved for registration of the NEMS score in the electronic medical record system. Identification of the nurse-recorder is assured by means of a personal code. Prior to the study no structured training programme for NEMS was offered. Patients ≥18 years of age, admitted to our ICUs between January 2010 and October 2010 were eligible. In view of the retrospective, non-interventional design of this quality assurance study, no informed consent was required by the Cantonal Ethics Committee.

In order to review a representative collective of NEMS scores among the 2,386 eligible patients we established a list of the 10 most frequent principal discharge diagnoses. For each diagnosis (number of patients drawn per centre) the primary investigator then randomly drew the names of the patients to be analysed, for a total of 30 patients per ICU: septic shock (5), acute ischaemic stroke (3), acute myocardial infarction (3), cardiopulmonary arrest (3), acute heart failure (3), acute respiratory failure due to pneumonia (3), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2), acute pancreatitis (2), polytrauma (2), arrhythmias (2) and patients with an ICU stay shorter than 24 hrs (2). Patients’ charts were then obtained by employees of the corresponding local quality control services and collocated for the review “in loco”.

One critical-care registered nurse and two experienced board registered intensivists were specifically trained for the use of NEMS and created a structured form for review based on the original definitions of the items necessary for NEMS [8].

The analysis was done by the three investigators by means of the above-mentioned template. The review process was performed in two steps. During the first stage the investigators independently examined the charts from all 30 patients and assessed the NEMS scores from the first 6 shifts (all shifts if length of stay <6 shifts). The results were evaluated, differences between the reviewers’ judgments were resolved by discussion and a final consensus (reference value) was achieved. Errors leading to differences between reviewers were categorised as follows: (1.) correlated to the definition (an item misclassified due to wrong application of definitions, e.g. by scoring an intervention not supposed to be so); (2.) due to negligence (if misclassification was based on insufficient chart examination, e.g. by ignoring an intervention) or (3.) due to other mechanisms (neither of the former was applicable).

The second step in the analysis served for comparison between the nurse registered NEMS scores (retrieved from the electronic medical record system by the primary investigator) and the reference value. This procedure was repeated in all four hospitals for a total of 120 patient charts. For each patient the following data were registered: (1.) primary discharge diagnosis; (2.) every variable of the NEMS score; (3.) possible differences in the reviewers’ judgements and (4.) the differences between the nurse registered NEMS score and the reference value. The following variables were retrieved for the nurses who carried out the NEMS scoring: centre, gender, certification and duration of specific professional experience.

Agreement between reviewers was assessed by average measure interclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with Spearman-Brown correction for continuous variables (sum-scores) and with weighted kappa statistics (and 95% confidence interval) for analysis of the different NEMS items. Kappas were calculated only for items where more than 20% of the values differed from baseline [14]. Mean agreement for the sum-scores and for items between reviewers was assessed by calculating their mean % of identical classifications among pair of reviewers. Perfect agreement was defined as identical categorisation of sum-scores and items.

Differences in the sum-scores were assessed by paired t-test. The mean difference (with 95% CI) and the mean absolute difference (i.e. the mean of the value of the difference) between NEMS scores (nurses minus reference value) were calculated. We also assessed the agreement of the sum-scores (reference value – nurse value) by Bland & Altman [15], and performed a simple regression analysis on the plotted Bland & Altman analysis to determine whether the difference (nurses minus reference value) changed depending on the sum-score. Weighted kappa statistics for analysis of the different NEMS items were calculated. Kappas were calculated only for items where more than 20% of the values differed from baseline [14]. Further, a univariate analysis was done to define risk factors for the occurrence of an error in items or sum-scores, including centres and nurse characteristics (gender, professional experience, certification). Results are shown as odds ratios (OR; 95% CI) to estimate the effect size of risk factors associated with an erroneous estimation. A multivariate logistic regression was performed to obtain adjusted estimates of the ORs and to identify factors independently associated with errors, always including for the model the following variables (the 4 centres and the 3 nurse characteristics: gender, certification and duration of experience). The multivariate analysis was performed only for those items with sufficient errors to render the analysis possible: assuming that for each of the 6 predictor variables (centres and nurse characteristics) considered, about 5–10 events should be available, we needed a minimum of 30 and a maximum of 499 errors.

Variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) if not specified otherwise. A p <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with Stata statistical software, release 11.0® (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA) and Statview (SAS institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA).

The three reviewers assessed a total of 529 different NEMS scores (4,761 variables); 184 cases (4% of all variables) where assessment diverged between reviewers and the reference value had to be defined by consensus. Agreement for sum-scores among reviewers was almost perfect (mean ICC = 0.9931 / significant correlation p <0.0001 / p for significant difference >>0.05). Reviewers’ agreement regarding the single variables (table 1) ranged from 0.95 (intravenous medication, supplementary ventilatory care, single vasoactive medication) to 1.0 (basic monitoring). Errors in reviewers’ assessment (table 2) were basically due to negligence or a problem related to the definition of the variable.

Figure 1

Linear regression between the difference (reference value – nurse value) of the NEMS sum-score and the mean NEMS sum-score [(reference value + nurse value) x 0.5].

The nurse registered NEMS score (mean ± SD) was 24.8 ± 8.6 points versus 24.0 ± 8.6 points (p <0.13) of the reference value. Among the 529 NEMS scores, 259 (47%) differed from the reference value in at least one variable. Table 3 shows the accuracy in nurses’ assessment of the single items when compared to the reference value. There was almost perfect agreement in the variables multiple vasoactive medication and mechanical ventilatory support, and it was still substantial for intravenous medication and specific interventions in the ICU. Accuracy across different hospital sites was similar: on average, NEMS scores were slightly overscored throughout all 4 ICUs, each of them, though, presenting different biases and dispersions (table 4). Bland & Altman (reference value – nurse registered NEMS score) was 0.84 ± 10, with a significant correlation between the difference and the reference value, indicating overall an overestimation of lower scores (≤29 points) and underestimation of higher scores with differences between centres (fig. 1).

A total of 134 nurses established the 529 NEMS scores. In the multivariate model quality of assessment was not associated with the hospital site, gender, certification and duration of specific professional experience, with all OR (95%CI) not significantly different from 1.0.

| Table 1: Agreement between reviewers for the single items of the NEMS score. | ||

| Item | Kappaa | Agreementb |

| Basic monitoring | NA | 1 |

| Intravenous medication | 0.84 | 0.95 |

| Dialysis techniques | NA | 0.99 |

| Specific interventions in the ICU | NA | 0.97 |

| Specific interventions outside the ICU | NA | 0.97 |

| Mechanical ventilatory support | 0.76 | 0.98 |

| Supplementary ventilatory care | 0.84 | 0.95 |

| Single vasoactive medication | 0.76 | 0.95 |

| Multiple vasoactive medication | NA | 0.99 |

| a Mean weighted Kappa of the 3 reviewers vs reference value. b Mean proportions of agreement among the 3 reviewers vs reference value. NA not applicable; no reliable Kappa statistics (≤20% of results differ from norm). | ||

| Table 2: Differences between the reviewers’ judgments according to the mechanism of error. | ||||

| Item | Cases | Mechanism of error | ||

| n (%) | Definitiona (n) | Negligenceb (n) | Othersc (n) | |

| Basic monitoring | ||||

| Intravenous medication | 39 (21) | 6 | 30 | 3 |

| Dialysis techniques, all | 7 (4) | 4 | 3 | |

| Interventions in the ICU | 26 (14) | 10 | 9 | 7 |

| Interventions outside the ICU | 25 (14) | 6 | 11 | 8 |

| Mechanical ventilatory support | 17 (9) | 9 | 7 | 1 |

| Supplementary ventilatory care | 27 (15) | 6 | 16 | 5 |

| Single vasoactive medication | 36 (19) | 4 | 30 | 2 |

| Multiple vasoactive medication | 7 (4) | 1 | 6 | |

| Total | 184 | 42 (23) | 113 (61) | 29 (16) |

| a A problem related to the definition of variables and its application (e.g., type of intervention in the ICU). b Insufficient examination of charts (e.g., erroneous exclusion of a specific intervention by lapse). c Other mechanism (e.g., insufficient available data in the chart). | ||||

| Table 3: Accuracy of assessment of the single items by nurses compared to the reference value. | ||||

| Item | Kappaa | Agreementb | NEMSc | |

| Nurse | Reference | |||

| Basic monitoring | NA | 1 | 9.0 ± 0.0 | 9.0 ± 0.0 |

| Intravenous medication | 0.32* | 0.85 | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 4.9 ± 2.3 |

| Dialysis techniques | NA | 0.98 | 0.2 ± 1.1 | 0.2 ± 1.1 |

| Specific interventions in the ICU | NA | 0.88 | 0.6 ± 1.6 | 0.3 ± 1.1 |

| Specific interventions outside the ICU | NA | 0.92 | 0.4 ± 1.4 | 0.4 ± 1.5 |

| Mechanical ventilatory support | 0.89 | 0.95 | 4.1 ± 5.7 | 3.8 ± 5.6 |

| Supplementary ventilatory care | 0.79 | 0.90 | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.8 ± 1.5 |

| Single vasoactive medication | 0.78 | 0.90 | 2.4 ± 3.3 | 2.6 ± 3.4 |

| Multiple vasoactive medication | NA | 0.97 | 1.0 ± 3.3 | 1.0 ± 3.4 |

| a Mean weighted Kappa of the 529 nurse registered NEMS scores vs. reference value. b Mean proportions of agreement of the nurses vs. reference value. c Mean points (±SD) of categorical values. NA not applicable; no reliable Kappa statistics (≤20% of results differ from norm). * 22% of results differ from reference value. | ||||

| Table 4: Agreement of nurse assessed NEMS sum-scores according to the ICU site. | |||||

| ICC | Δ NEMS | SD | Dispersion | ||

| Centre | RV – nurses | minimum | maximum | ||

| A | 0.90 | –0.27 | 4.6 | –13 | 15 |

| B | 0.75 | –1.20 | 5.5 | –18 | 15 |

| C | 0.81 | –0.49 | 4.8 | –23 | 16 |

| D | 0.79 | –1.57 | 5.2 | –25 | 16 |

| All | 0.83 | –0.84 | 5.0 | –25 | 16 |

| ICC Intraclass Correlation Coefficient Δ NEMS difference in NEMS scores between reference value (RV) and nurses SD standard deviation | |||||

Our multicentre study shows that nurse-registered NEMS scores are highly accurate, even without a specific and regular training programme, thus reflecting our real life situation. Intravenous medication and specific interventions in the ICUwere the most error-prone items and mistaken assessment was not associated with the nurses’ characteristics assessed.

Astonishingly, the agreement on the item intravenous medication – although apparently simple – was lowest for both nurses and reviewers. With this retrospective audit we were unable to disclose the mechanisms by which nurses made mistakes in assessing NEMS scores. However, we could show that professional experience and certification had no impact on the occurrence of errors, neither was there a general centre effect. The analysis of the three reviewers’ most frequent problems in defining the reference value might give some insight (table 2). In this sense, negligence was the most common source of reviewers’ erroneous assessment, and many such disagreements were readily clarified by chart re-examination. Problems related to definition of the variables as well as lack of interest in scoring should also be considered. It is important to emphasize that our nurse-registered NEMS scores are based on manual acquisition of data. The nurses rely on previously registered data from the daily patient survey charts and eventually insert manually the items in the electronic medical record. Fully automatic calculation of the NEMS using a Patient Data Management System (PDMS) database has shown itself feasible and accurate [16]. The integration of item definitions in the automatic data acquisition system could help to lessen misclassification problems by switching the responsibility of appropriate scoring from the nurses to the PDMS. Moreover, failure in notifying resource use – such as mechanical ventilation or intravenous vasotropic agents – could be prevented thanks to a direct linkage between electronic devices. Besides these benefits, such a measurement tool could also diminish the time spent in administrative activity. Nevertheless, some kinds of neglicence (specific interventions in/outside the ICU) were still hard to avoid, as they must be specifically declared by the nurse.

On average, lower NEMS scores (≤29 points) were rather overestimated and higher scores underestimated. Thus, nurses might have erroneously attributed resource use in mild cases (e.g., due to a problem of definition) or forgotten to score items in severely ill patients (e.g., due to negligence and/or a problem of definition). Exclusion of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures may thus seriously affect the NEMS score. As the systematic underestimation of high NEMS scores might considerably diminish the overall degree of hospital reimbursement, suitable countermeasures are imperatively required. As already mentioned above, automatic retrieval of variables is highly accurate [16] and might theoretically increase scores through a smaller number of missing components and a correct interpretation of data. Exact acquisition and correct transmission of related data are definitely essential, but without fine knowledge of the definitions and their exact application, NEMS scores will hardly become more accurate. Thus, a structured training programme will be implemented in our department to increase understanding and motivation.

A strength of our study is probably the conception of a multidisciplinary reference value (nurse and intensivists) that served for comparison with the nurse assessed NEMS scores. Ultimately there was excellent agreement among reviewers regarding the different items and the sum-scores. In addition, the multicentre design of this study probably permits a certain generalization of our results, although the retrospective execution may somewhat lessen its extent. However, as the major problem in assessing was omission of items (leading to an underscoring of higher and more rewarded NEMS scores), we do not believe that a prospective audit would have strikingly changed our results. Among the limitations we should stress that we examined multiple NEMS scores (up to 6) for every patient randomly chosen. Some particular characteristics of a given patient could have influenced the results, even if, due to the number of patients included, to a limited extent.

In conclusion, our study suggests that nurse-registered NEMS scores are highly accurate and not influenced by different backgrounds, levels of training and gender. Higher (and more rewarded) NEMS scores tended to be underestimated. A multifaceted improvement intervention, based on automatic (computer-based) retrieval of the items and implementation of a structured training programme, is warranted.

| Appendix 1: The nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS). | ||

| Action | Points | Explications |

| Basic monitoring | 9 | Hourly vital signs, regular record and calculation of fluid balance. |

| Intravenous medication | 6 | Bolus or continuously, not including vasoactive/inotropic drugs. |

| Mechanical ventilatory support | 12 | Any form of mechanical/assisted ventilation for ≥2 hrs/shift (excludes supplementary ventilatory care). |

| Supplementary ventilatory care | 3 | Breathing spontaneously through endotracheal tube; supplementary oxygen any method. |

| Single vasoactive medication | 7 | Any vasoactive/inotropic drug, continuously intravenous. |

| Multiple vasoactive medication | 12 | More than one vasoactive/inotropic drug, regardless of type and dose, continuously intravenous. |

| Dialysis techniques | 6 | All |

| Specific interventions in the ICU | 5 | Such as endotracheal intubation, introduction of pacemaker, cardioversion, endoscopy, emergency operation, in the past 24 h, gastric lavage. Routine interventions such as X-rays, echocardiography, electrocardiography, dressings, introduction of venous or arterial lines, are not included. |

| Specific interventions outside the ICU | 6 | Such as surgical intervention or diagnostic procedure; the intervention/procedure is related to the severity of the patient’s illness and makes an extra demand upon manpower efforts in the ICU. |

| NEMS scoring system used by the members of the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine (slightly adapted from [8]). | ||

| Appendix 2: Structured form for the evaluation of the NEMS scores. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rilevamento NEMS | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monit (9) | Medi (6) | Emo (6) | AI (5) | AE (6) | Vent (12) | AR (3) | 1 va (7) | >1 va (12) | Totale | ||||||||||||||

| Osp | No.paz. | Turno | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | Rev | Nurse | |

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monitor: tutti parametri ogni ora, incl. bilancio. Medicamenti: medi endovena (bolo ò infusione picc.); non infusione di base / per tener aperta la via. Atti interni: non sono, ECG, Rx, CVC, cat. art. Atti esterni: OP, TAC, RMI. Ventilazione: ogni forma invasiva o non invasiva; ≥2 ore. Assistenza respiratoria: O2 supplementare; respiro spontaneo al tubo / tracheostoma. 1 vasoattivo: ogni vasoattivo/inotropico se di continuo endovenoso. >1 vasoattivo: come sopra, ma >1 vasoattivo/cardiotropico in contemporanea. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the local quality managers (Adriana De Giorgi, Moreno Doninelli, Paola Buletti, Angela Greco, Mario Lazzaro) for their collaboration and helpful advice.

1 Needleman J, Buerhaus P, Mattke S, Stewart M, Zelevinsky K. Nurse-staffing levels and the quality of care in hospitals. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1715–22.

2 Thorens JB, Kaelin RM, Jolliet P, Chevrolet JC. Influence of the quality of nursing on the duration of weaning from mechanical ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Crit Care Med. 1995;23:1807–15.

3 Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM, Sochalski J, Silber JH. Hospital nurse staffing and patient mortality, nurse burnout, and job dissatisfaction. JAMA. 2002;288:1987–93.

4 Noseworthy TW, Konopad E, Shustack A, Johnston R, Grace M. Cost accounting of adult intensive care: methods and human and capital inputs. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1168–72.

5 Cullen DJ, Civetta JM, Briggs BA, Ferrara LC. Therapeutic intervention scoring system: a method for quantitative comparison of patient care. Crit Care Med. 1974;2:57–60.

6 Keene AR, Cullen DJ. Therapeutic intervention scoring system: update 1983. Crit Care Med. 1983;11:1–3.

7 Miranda DR, de Rijk A, Schaufeli W. Simplified therapeutic intervention scoring system: the TISS-28 items results from a multicenter study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:64–73.

8 Reis Miranda D, Moreno R, Iapichino G. Nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS). Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:760–5.

9 Le Gall J-R, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F. A new simplified acute physiology score (SAPS II) based on a European / North American multicenter study. JAMA. 1993;270:2957–63.

10 Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information. OPS Version 2011, Kapitel 8 Nichtoperative Therapeutische Massnahmen 8-98. Available via http://www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassi/prozeduren/ops301/opshtml2011/block-8-97...8-98.htm Accessed June 23, 2011.

11 SwissDRG, Schweizerische Operationsklassifikation (CHOP), Systematisches Verzeichnis, Vers 2011 – 2. November 2010; Publikation komplett: p 280–281. Available from: http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/news/publikationen.html?publicationID=4096 Accessed June 23, 2011.

12 Schuetz P, Albrich WC, Suter I, Hug BL, Christ-Crain M, Holler T, et al. Quality of care delivered by fee-for-service and DRG hospitals in Switzerland in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13228. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13228.

13 Frutiger A. Qualitätssicherung in der Intensivmedizin: die Situation in der Schweiz. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1999;129:1592–9.

14 Sim J, Wright CC. The kappa statistic in reliability studies: use, interpretation, and sample size requirements. Phys Ther. 2005;85:257–68.

15 Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10.

16 Junger A, Brenck F, Hartmann B, Klasen J, Quinzio L, Benson M, et al. Automatic calculation of the nine equivalents of nursing manpower use score (NEMS) using a patient data management system. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:1487–90.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.