Figure 1

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2012.13544

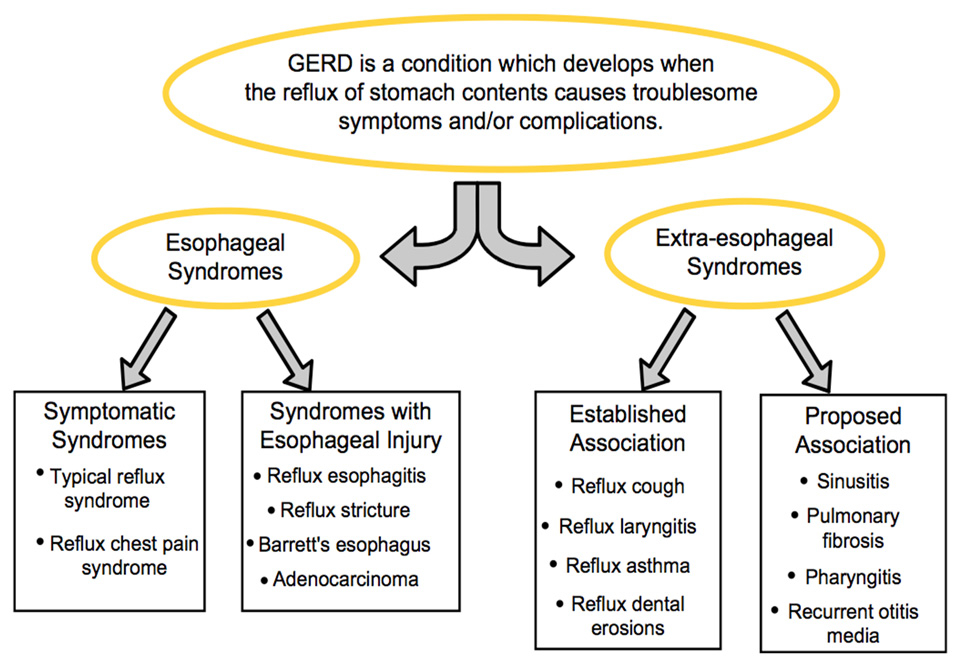

Extraesophageal reflux disease (EERD) represents a wide spectrum of manifestations mainly related with the upper and the lower respiratory system such as laryngitis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cough, hoarseness, postnasal drip disease-sinusitis, otitis media, recurrent pneumonia and laryngeal cancer. Non-cardiac chest pain is commonly grouped among the esophageal syndromes by the Montreal Classification [1] (fig. 1), but is not one of the common symptoms of typical gastroesophageal reflux (GER) which are heartburn and regurgitation [2]. The diagnosis and recommendations on initial empiric therapy for patients with suspected reflux related non-cardiac chest pain is similar to those of extraesophageal reflux which is why it is included in this chapter.

Figure 1

GER contributes to extraesophageal syndromes by two mechanisms: direct (aspiration) or indirect (vagally-mediated) mechanisms [1, 3–6]. Reflux of gastroduodenal contents into the esophagus and hypophayrnx may be classified as either “high” or “distal” [7]. The pathogenesis of “high” esophageal reflux involves reflux that traverses the esophagus and induces cough either by direct pharyngeal or laryngeal stimulation or aspiration and causes a tracheal or bronchial cough response. In “distal” esophageal reflux, cough can be produced by a vagally-mediated tracheal-bronchial reflex [7, 8]. Embryologic studies show that esophagus and bronchial tree share a common embryologic origin and neural innervation via the vagus nerve. Pressure gradient changes between the abdominal and thoracic cavities during the act of coughing, may lead to a cycle of cough and reflux [8, 9]. A disturbance in any of the normal protective mechanisms such as disruption of the mechanical barrier for reflux (lower esophageal sphincter) or esophageal dysmotility may allow direct contact of noxious gastroduodenal contents with the larynx or the airway [10, 11].

In this article we will discuss the latest knowledge of the association between extraesophageal manifestations of GER such as chronic cough, laryngitis and asthma as well as non-cardiac chest pain of esophageal origin. We will discuss the current recommendations on diagnosis and treatment options for this difficult group of patients.

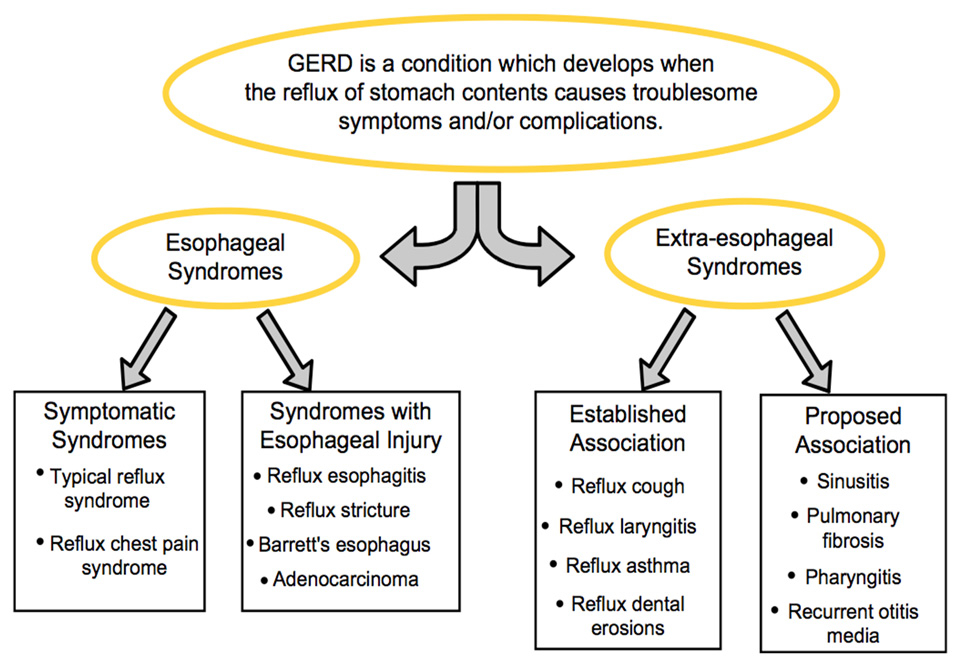

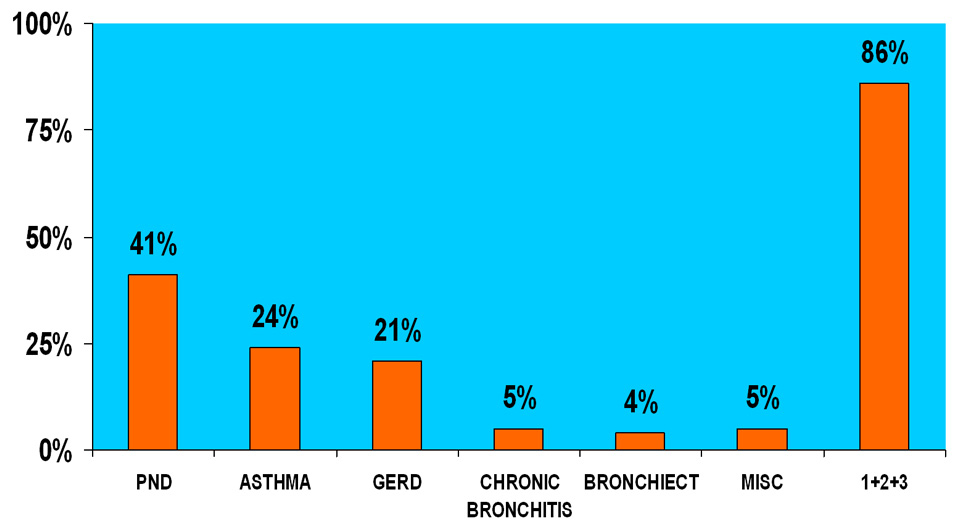

Chronic cough, defined as cough >8 weeks duration, is a common condition evaluated by physicians in the U.S. [12, 13]. In non-smoking patients with normal chest X-rays, who are not taking angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, the most common causes of cough include postnasal drip syndrome (PNDS), asthma, gastroesophageal reflux and chronic bronchitis, and these four conditions may account for up to 90% of cases of chronic cough [14] (fig. 2). Poe et al. found that GER alone accounted for cough in 13% of their study population, while in 56% of patients, it was a contributing factor to persistence of cough [8]. Evaluation of chronic cough generally begins with the diagnostic protocol developed by Irwin et al. [15]. This protocol evaluates the chronic cough patients who have normal chest X-rays and are not taking ACE inhibitors, for the three most common causes of cough: postnasal drip syndrome (PNDS), asthma, and GER. Once PNDS and asthma have been excluded, patients can then undergo evaluation for GER. It is important to recognise that chronic cough can occur by at least two mechanisms: 1) direct reflux of gastroduodenal contents in which case laryngitis may be evident by laryngeal evaluation. In this case patients may be diagnosed with laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) and appropriately treated. 2) Chronic cough may also occur indirectly via vagal mechanisms in which case laryngeal irritation may not be evident.

Figure 2

The diagnosis of GER associated chronic cough may be challenging, as many patients do not always exhibit typical reflux symptoms. It is estimated that up to 75% of patients with GER-associated cough do not display classic symptoms of reflux (i.e., heartburn and regurgitation) [4, 16]. Everett et al. found that only 63% of cough patients studied displayed the classic symptoms of reflux [17]. Patients with GER-associated cough may describe a cough that occurs primarily during the day, in the upright position, during phonation, when rising from bed or cough associated with eating. The process is further complicated by the fact that there is no diagnostic test that is definitive in identifying GER as a cause of chronic cough.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) and 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring have some inherent problems when employed to evaluate reflux as a cause of chronic cough. EGD is used to evaluate the presence of esophagitis and other mucosal abnormalities such as Barrett’s esophagus in suspected patients with GER. The difficulty in using this test as a diagnostic tool in reflux-associated cough is that there is often poor correlation between findings of esophagitis and patients’ cough. For example, Baldi et al. evaluated 45 patients suffering from chronic cough with EGD [14]. 55% of their study group complained of classic reflux symptoms; however, only 15% of the study population had endoscopy-proven esophagitis. Thus, there is low sensitivity for EGD in establishing a link between chronic cough and esophageal findings. Most patients with chronic cough will have normal endoscopy findings.

24-h esophageal pH monitoring has 90% sensitivity in diagnosing abnormal esophageal acid exposure in patients with GER; however, it has limitations in patients with chronic cough, and is shown to have specificity as low as 66% in this population [7, 9, 18–21]. One important utility of pH monitoring in chronic cough may be the ability to correlate esophageal reflux episodes with cough symptoms by employing the two most commonly used indices; symptom index (SI) or symptom association probability (SAP). However, a recent study by Slaughter et all concluded that both SI and SAP indices can be over-interpreted and are prone to mis-interpretation. They suggested that unless patients with GER refractory to PPI therapy have high rates of esophageal acid exposure both SI and SAP indices are essentially chance occurrences at best [22]. Baldi et al. employed 24-h pH monitoring in their study evaluating patients with reflux-associated chronic cough [14]. They found 53% of the patients had pathological reflux; however, when compared with other, less invasive tests, such as treatment with proton pump inhibitors, esophageal pH monitoring was felt to have a low diagnostic gain. This is supported in a study by Ours et al. which found that pH monitoring was not a “reliable predictor of acid reflux-induced chronic cough” because only 35% of patients in their study population with abnormal pH-metry responded to PPI therapy [12]. The authors concluded that the cost-effectiveness of using empiric PPI treatment for GER-associated cough was superior to other diagnostic modalities such 24-h pH monitoring [12, 18].

The use of empiric therapy of PPI’s to both diagnose and treat GER-associated chronic cough has also been studied by Poe et al. who were able to diagnose 79% of patients with cough secondary to GER with resolution of symptoms after empiric trial of PPI therapy [8]. Most experts recommend twice daily initial dosing for PPI use in chronic cough. However, a recent study by Baldi et al. suggested that once daily PPI therapy may be similar to twice daily therapy. They evaluated chronic cough patients who were treated with a 4-week open-label course of 30 mg lansoprazole bid and monitored for response [14]. Patients whose symptoms responded were then treated with either 30 mg lansoprazole once a day or 30 mg lansoprazole twice a day for 12 weeks. Results found no significant difference in symptom improvement between the two dosing regimens. Only 23% of patients who did not respond after the initial 4weeks of therapy obtained complete symptom relief. This study suggests that patients who are likely to achieve complete response are the ones with their symptoms being improved in a short period of time [14]. Additionally, we recently showed that the response to surgical intervention of patients with chronic cough may be dependent on concomitant baseline presence of typical symptoms of GERD (heartburn and regurgitation) [23].

In conclusion, the evaluation of chronic cough should begin with evaluation for other causes of chronic cough such as PNDS and asthma in patients having normal chest X-rays and no history of using ACE inhibitors. After these have been ruled out, an empiric trial of acid suppression with bid PPI therapy for 12–16 weeks will likely identify and treat the majority of patients with reflux-associated chronic cough. Those who remain unresponsive may have other tests to exclude large mechanical defect such as hiatal hernia causing volume regurgitation or evaluation for other lung related issues.

GER is implicated as an important cause of laryngeal inflammation [24]. Common reported symptoms of this condition, also termed laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) by the ENT physicians, include hoarseness, throat pain, sensation of a lump in the throat, cough, repetitive throat clearing, excessive phlegm, difficulty swallowing, pain with swallowing, heartburn, and voice fatigue (table 1). These symptoms are nonspecific and can also be seen in patients with postnasal drip, and environmental exposures to allergens, or other irritants such as smoke [25]. However, reflux is often implicated in many patients given chronicity of symptoms and laryngeal findings of erythema and edema. The most common laryngeal signs associated with LPR are listed in tables 2.

24 hour pH monitoring and laryngoscopy are the two common tests for the diagnosis of reflux associated laryngeal symptoms. Intraluminal impedance combined with pH testing is also recently employed in evaluation of this group of patients. The role of pH or impedance monitoring in establishing a relationship between gastroesophageal reflux and laryngopharyngeal reflux is still less than clear, and its application in the diagnosis of reflux laryngitis may not be as useful as once thought [24]. A recent review of studies evaluating pharyngeal reflux in healthy volunteers demonstrated that anywhere from 19% to 43% of normal people can be expected to have pharyngeal reflux events by hypopharyngeal pH monitoring [26]. There was no difference in the prevalence of pharyngeal reflux events in symptomatic patients versus normal volunteers. Intraluminal impedance testing is an ambulatory method used for detecting nonacid reflux, especially in those who continued to have symptoms despite PPI therapy. This test detects reflux events based on changes in resistance to electrical current flow between electrodes on the catheter placed in the esophagus. Outcome studies with this device are lacking and the clinical relevance of impedance findings in LPR patients who continue to have symptoms despite PPI therapy still remains uncertain. We recommend the use of pH monitoring off PPI therapy to provide baseline esophageal reflux parameters. Impedance monitoring must be conducted on PPI therapy and should be reserved for those who continue to have symptoms despite acid suppressive therapy. In the setting of moderate to severe baseline acid reflux off therapy and continued non-acid reflux on PPI therapy antireflux surgery may be entertained but with caution.

Laryngoscopy is one of the most common tests used to diagnose GER-related laryngitis; however, its specificity is not promising. The initial correlation between GER and laryngitis was established in the 1960’s, and involved laryngoscopy to visualise vocal cord ulcerations in the larynx in symptomatic patients with GER [27, 28]. Since that time other signs of laryngeal irritation, such as posterior cricoid erythema, vocal cord erythema/edema, and arytenoid erythema/edema have been used to diagnose and subsequently treat patient with GER-associated laryngitis [10] (table 2). However, due to the non-specific nature of the laryngeal signs for LPR, the utility of laryngoscopy in detecting GER-associated laryngitis, though common, remains uncertain [29, 30]. Milstein et al. who evaluated 52 non-smoker volunteers with no history of ENT abnormalities or GERD highlighted the non-specific nature of laryngeal evaluation. This group underwent both rigid and flexible video laryngoscopy. The authors found that in this asymptomatic normal population there was at least one sign of tissue irritation in 93% of flexible and 83% of rigid laryngoscopic evaluation. Additionally, the findings were dependent on the technique. Laryngeal signs were more commonly reported on flexible transnasal laryngoscopy than with the rigid transoral examination [30]. The high prevalence of laryngeal irritation in normal volunteers combined with the variability of the diagnosis based on methods employed highlights the uncertainty associated with laryngeal signs in LPR.

In 2007, Vavricka et al. evaluated the prevalence of specific laryngopharyngeal changes associated with GER in patients with known reflux disease (n = 132) versus normal subjects (n = 132) [31]. Ten specific hypopharyngeal and laryngeal sites were evaluated; including posterior pharyngeal wall, interarytenoid bar, posterior commissure, posterior cricoid wall, arytenoids complex, true vocal fords, false vocal cords, anterior commissure, epiglottis and aryepiglottic fold. Investigators found that the prevalence of laryngeal lesions once thought GER-related, was the same in both groups. Only posterior pharyngeal wall abnormalities including erythema, edema, and cobblestoning, showed a statistically significant higher prevalence in GER patients as compared to the control group. However, given the high level of variability in diagnosing subjective signs such as erythema and edema in the larynx it is not unusual that LPR is often over diagnosed in those with chronic throat symptoms.

Proton pump inhibitor therapy is also the standard of care if GER is suspected as the etiology for patients’ chronic throat symptoms. However, the most recent large scale multi center study of 145 patients suspected of having LPR did not show a benefit in those treated for 4months with esomeprazole 40 mg BID compared to placebo for a duration of 16 weeks [32]. The disappointing negative findings from this study and other controlled trials in LPR stems from the dilution effect of patients enrolled in these trials. Given lack of a gold standard diagnosis for GER in patients with LPR, many patients may not have had the disease for which they were being randomised. Otolaryngologists usually suspect GER-related laryngitis based on symptoms such as throat clearing, cough, and globus and signs such as laryngeal edema and erythema; which as previously eluted to as non-specific for reflux. The group of patients who are unresponsive to PPI therapy have either non-reflux related causes or may have functional component to their symptoms. The placebo response rate of around 40% in LPR studies seem similar to the ones in functional gastrointestinal disorders such as irritable bowel syndrome [33].

Thus, suspected LPR patients without warning symptoms or signs should initially be treated with empiric PPI therapy for a duration of one to two months. If symptoms improve the therapy may need to be prolonged up to 6 months to allow healing of laryngeal tissue after which the dose should be tapered to minimal acid suppression resulting in continued response. In unresponsive patients testing with impedance and/or pH monitoring on therapy may be the best alternative to rule out reflux as the cause and to move forward with considering other causes for patients’ continued symptoms.

| Table 1: Symptoms attributed to laryngopharyngeal reflux. |

| – Hoarseness |

| – Dysphonia |

| – Sore or burning throat |

| – Excessive throat clearing |

| – Chronic cough |

| – Globus |

| – Dysphagia |

| – Postnasal drip |

| – Laryngospasm |

| Table 2: Potential laryngopharyngeal signs associated with GER. |

| Edema and hyperemia of larynx |

| Hyperemia and lymphoid hyperplasia of posterior pharynx (cobblestoning) |

| Granuloma |

| Contact ulcers |

| Laryngeal polyps |

| Interarytenoid changes |

| Reinke’s edema |

| Tumors |

| Subglottic stenosis |

| Posterior glottic stenosi |

Asthma has a strong correlation with GER and the conditions seem to induce the other. GER can induce asthma by the vagally-mediated or microaspiration mechanisms described above. Asthma can induce reflux by several mechanisms. An asthma exacerbation results in negative intrathoracic pressure, which may cause reflux and the medications used to treat asthma (theophylline, beta-agonists, steroids) can reduce the lower esophageal sphincter. Patients with asthma whose symptoms are worse after meals, or those who do not respond to traditional asthma medications should be suspected of having GER. Patients who have heartburn and regurgitation before the onset of asthma symptoms may also be suspected of having reflux induced asthma symptoms.

There is an established association between asthma and gastroesophageal reflux based on both epidemiologic studies as well as physiologic testing with ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring [34, 35]. In a study evaluating the prevalence of GER in asthma patients, Kiljander et al. found that 35% of GER related patients did not express the typical reflux symptoms, but were found to have abnormal esophageal acid exposure by pH monitoring [34]. Similarly, Leggett et al conducted a study assessing GER in patients with difficult to control asthma using 24-hour ambulatory pH probes with both distal (5 cm above the lower esophageal sphincter) and proximal (15 cm above the lower probe) probes [36]. They reported an overall prevalence of reflux at the distal probe to be 55%, and that in the proximal probe to be 35% [36]. Thus, reflux is a common occurrence in patients with asthma.

There is controversy regarding the benefit of PPI use in patients suspected of having reflux-induced asthma. Studies have employed different endpoints regarding efficacy of acid suppressive therapy in this group. Some employ objective measurements such as improvement in FEV1 while others rely on patient reported questionnaires or decreasing need for asthma medications. Early trials reported improvements in pulmonary symptoms and pulmonary function in patients treated with acid suppressive therapy [37]. In 1994, Meier et al. conducted a double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study which evaluated pulmonary function of asthma patients treated with 20 mg of omeprazole twice a day for six weeks. This study found that 27% (4 of 15) patients with reflux had a > or = to 20% increase in FEV1 [38].

In another study, Sontag et al. [37] evaluated 62 patients with both GER and asthma and divided the group into three treatment arms: control, treatment of reflux with ranitidine 150 mg three times a day, or surgical treatment with Nissen fundoplication. After a two year follow up 75% of surgical patients had improvement in nocturnal asthma exacerbations, compared to 9.1% and 4.2% of patients on medical therapy and controls, respectively. Additionally, there was a statistically significant improvement in mean asthma symptom score, but no improvement in pulmonary function or reduction in the need for medication between the groups. Littner et al followed 207 patients with symptomatic reflux, who were treated with either placebo or a proton pump inhibitor twice a day for 24 weeks. The primary outcome of the study was daily asthma symptoms by patient diary, and secondary outcomes included the need for rescue albuterol inhaler use, pulmonary function, asthma quality of life, investigator assessed asthma symptoms and asthma exacerbations. The study showed that medical treatment of reflux did not reduce daily asthma symptoms or albuterol use and did not improve pulmonary function in this group of asthmatic patients [39]. Similarly, a recent study conducted by the American Lung Association Asthma Clinical Research Center [40] randomised 412 patients with poor asthma control to either esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily or placebo. After 24 weeks of follow up, the study found no treatment benefit to PPI therapy in asthma control. A Cochrane review of GER treatment for patients with asthma found only minimal improvement of asthma symptoms with reflux therapy [41]. Encouragingly, a recent controlled trial in asthmatics suggested therapeutic benefit with PPIs in the sub-group of asthmatics with both nocturnal respiratory and GER symptoms [42]. Thus, the issue of asthma control by treating reflux in patients who have asthma is not yet clear.

Therefore, the current recommendation in patients with asthma (with or without concomitant heartburn or regurgitation) is similar to those in patients with chronic cough and laryngitis, suggesting the initial empiric trial of twice daily PPI’s for 2–3 months. In those responsive to therapy for both heartburn and/or asthma symptoms, PPI’s should be tapered to the minimal dose necessary to control symptoms. In unresponsive patients, testing for reflux, by pH testing and/or impedance-pH monitoring may be needed to measure for continued reflux of acid or non-acid material, which could still be responsible for patients’ asthma exacerbation.

Non-cardiac chest pain is defined as recurring angina-like retrosternal chest pain in patients with negative cardiac evaluation [43, 44]. GER is recognised as the most common underlying cause of non-cardiac chest pain [43]. The diagnosis of esophageal related non-cardiac chest pain is often difficult. Clinically, cardiac chest pain and chest pain of esophageal origin often share a similar presentation. The pain of both may be similar in description (often described as burning, pressure-like, substernal or occurring with exercise) and may be improved with similar treatments (i.e., nitroglycerin) [43]. Pain that is post-prandial, continues for hours, is retrosternal without radiation, relieved with antacids, and pain that disturbs sleep makes the diagnosis of GER related chest pain more likely [45]. However, by definition non-cardiac chest pain implies that cardiac causes for patients have been ruled out.

Direct contact of the esophageal mucosa with gastroduodenal agents such as acid and pepsin, leading to vagal stimulation is the most likely cause of these symptoms [46, 47]. Esophageal motility disorders such as nutcracker esophagus or diffuse esophageal spasm can also cause non-cardiac chest pain. Thus, in patients with non-cardiac chest pain where GER is treated and patients continue to have symptoms, esophageal motility testing would be the next step in order to rule out motility disorders.

The differentiation of angina and non-cardiac chest pain can be difficult, as GER and coronary artery disease (CAD) often co-exist. Reflux can be worsened with exercise and can cause non-cardiac chest pain. Medications such as nitroglycerin and calcium channel blockers used to treat angina may also relieve symptoms caused by esophageal spasm. These medications can also relax the lower esophageal sphincter.

Obviously, classic reflux symptoms such as heartburn and regurgitation, in the absence of cardiac disease, make the diagnosis more likely. In fact, these symptoms have been found to be present in up to 83% of patients with chest pain related to an esophageal disorder [48]. In a study by Locke et al. non-cardiac chest pain was reported in 37% of patients with frequent heartburn symptoms, compared to 7.9% of patients reporting no GER symptoms [45].

Because the most common cause of non-cardiac chest pain is gastroesophageal reflux disease, several diagnostic tests used to diagnose GER may be employed in the evaluation of this group of patients [49]. 24-hour ambulatory pH testing is insufficient to be considered a gold standard for the diagnosis of GERD-related non-cardiac chest pain [50]. Its use in determining causality between reflux and noncardiac chest pain, however, is not as straight-forward [35]. Ahmed and Vaezi, examining the role of pH monitoring in non-cardiac chest pain found the overall prevalence of reflux by pH monitoring in non-cardiac chest pain patients was 41% [35]. Lacime et al. in a study of GERD-related non-cardiac chest pain, found abnormal pH parameters in 43% of their patient population, but only 17% of chest pain events were associated with reflux episodes [51]. Overall, pH monitoring has the capability to detect gastroesophageal reflux, but may not establish a link between chest pain episodes and reflux events [35].

Early studies on the role of EGD in patients with non-caridac chest pain found that only 10% to 25% of these patients had endoscopic evidence of esophagitis [52, 53]. Bautista et al. found that only 9.9% of patients with non-cardiac chest pain had evidence of mucosal erosions on endoscopy [54]. Dickman et al. compared endoscopic findings in patients with non-cardiac chest pain to the findings in patient with GER. 44.1% of patients in the non-cardiac chest pain group were found to have normal endoscopies, while 39% of the GER patients had a normal endoscopy. Overall, all GER-related mucosal findings were significantly less common in the non-cardiac chest pain group as compared to the GER group [55]. As in patients with extraesophageal reflux syndromes discussed above, there is limited role of EGD in patients with non-cardiac chest pain.

Empiric trial with proton pump inhibitor therapy has emerged as the first-line diagnostic tool in the evaluation of non-cardiac chest pain once cardiac etiology is ruled out. Achem et al. studied 36 patients who received 20 mg twice a day of omeprazole in a double-blind, placebo controlled study and found that 81% of treated patients reported symptom improvement when compared to 6% of patients receiving treatment with placebo [56]. Pandek et al. conducted a prospective, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study using high dose omeprazole treating patients with NCCP and found that 95% of patients with proven GER (positive results in 24-hour pH monitoring and/or esophagitis on endoscopy) responded [57]. In a study empirically treating patients with unexplained chest pain with omeprazole, Fass et al. found the sensitivity and specificity of empiric omeprazole to be 78% and 86% respectively [58]. In keeping with these results, Ofman et al. found that empiric omeprazole (when compared with traditional diagnostic procedures) resulted in an cost savings of $454 dollars per patient [59]. Thus, in patients without warning symptoms (such as dysphagia, weight loss or anemia), an empiric course of PPIs, used until symptoms remit, and then tapered to the lowest dose of proton pump inhibitor controls symptoms, is reasonable. Diagnostic testing with ambulatory pH or impedance monitoring and esophageal motility testing is usually reserved for those who continue to be symptomatic despite initial empiric trial of PPI therapy.

1 Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas P, Dent J, Jones R. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101(8):1900–20; quiz 43. Epub 2006/08/25.

2 Napierkowski J, Wong RK. Extraesophageal manifestations of GERD. Am J Med Sci. 2003;326(5):285–99. Epub 2003/11/15.

3 Field SK, Evans JA, Price LM. The effects of acid perfusion of the esophagus on ventilation and respiratory sensation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1058–62.

4 Ing AJ, Ngu MC, Breslin AB. Pathogenesis of chronic persistent cough associated with gastro-esophageal reflux. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994(99):2098–106.

5 Adhami T, Goldblum JR, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. The role of gastric and duodenal agents in laryngeal injury: an experimental canine model. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(11):2098–106. Epub 2004/11/24.

6 Tuchman DN, Boyle JT, Pack AI, Scwartz J, Kokonos M, Spitzer AR, et al. Comparison of airway responses following tracheal or esophageal acidification in the cat. Gastroenterology. 1984;87(4):872–81. Epub 1984/10/01.

7 Stanghellini V. Relationship between upper gastrointestinal symptoms and lifestyle, psychosocial factors and comorbidity in the general population: results from the Domestic/International Gastroenterology Surveillance Study (DIGEST). Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1999;231:29–37. Epub 1999/11/24.

8 Poe RH, Kallay MC. Chronic cough and gastroesophageal reflux disease: experience with specific therapy for diagnosis and treatment. Chest. 2003;123(3):679–84. Epub 2003/03/12.

9 Irwin RS. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux disease: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2006;129(1 Suppl):80S–94S. Epub 2006/01/24.

10 Johnson DA. Medical therapy of reflux laryngitis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(5):589–93. Epub 2008/04/23.

11 Vaezi MF. Extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5(4):32–8; discussion 9–40. Epub 2004/04/23.

12 Ours TM, Kavuru MS, Schilz RJ, Richter JE. A prospective evaluation of esophageal testing and a double-blind, randomized study of omeprazole in a diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm for chronic cough. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(11):3131–8. Epub 1999/11/24.

13 Schappert SM. National ambulatory medical care survey, 1991: Summary. Vitals and Health Statistics No 230 US Department of Health and Human Service. 1993:1–20.

14 Baldi F, Cappiello R, Cavoli C, Ghersi S, Torresan F, Roda E. Proton pump inhibitor treatment of patients with gastroesophageal reflux-related chronic cough: a comparison between two different daily doses of lansoprazole. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(1):82–8. Epub 2006/01/28.

15 Irwin RS, Corrao WM, Pratter MR. Chronic persistent cough in the adult: the spectrum and frequency of causes and successful outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1981;123(4 Pt 1):413–7. Epub 1981/04/01.

16 Laukka MA, Cameron AJ, Schei AJ. Gastroesophageal reflux and chronic cough: which comes first? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1994;19(2):100–4. Epub 1994/09/01.

17 Everett CF ea. Clinical history in gastroesophageal cough. Resp Med. 2007(101):991–7.

18 Chandra KM, Harding SM. Therapy Insight: treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in adults with chronic cough. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;4(11):604–13. Epub 2007/11/06.

19 Irwin RS, Curley FJ, French CL. Chronic cough. The spectrum and frequency of causes, key components of the diagnostic evaluation, and outcome of specific therapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1990;141(3):640–7. Epub 1990/03/01.

20 Irwin RS, French CL, Curley FJ, Zawacki JK, Bennett FM. Chronic cough due to gastroesophageal reflux. Clinical, diagnostic, and pathogenetic aspects. Chest. 1993;104(5):1511–7. Epub 1993/11/01.

21 McGarvey LP, Heaney LG, Lawson JT, Johnston BT, Scally CM, Ennis M, et al. Evaluation and outcome of patients with chronic non-productive cough using a comprehensive diagnostic protocol. Thorax. 1998;53(9):738–43. Epub 1999/05/13.

22 Slaughter JC, Goutte M, Rymer JA, Oranu AC, Schneider JA, Garrett CG, et al. Caution about overinterpretation of symptom indexes in reflux monitoring for refractory gastroesophageal reflux disease. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology: the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2011. Epub 2011/07/26.

23 Francis DO, Goutte M, Slaughter JC, Garrett CG, Hagaman D, Holzman MD, et al. Traditional reflux parameters and not impedance monitoring predict outcome after fundoplication in extraesophageal reflux. The Laryngoscope. 2011;121(9):1902–9. Epub 2011/10/26.

24 Vaezi MF. Laryngitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease: increasing prevalence or poor diagnostic tests? Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(5):786–8. Epub 2004/05/07.

25 Diamond L. Laryngopharyngeal reflux – it’s not GERD. JAAPA. 2005;18(8):50–3. Epub 2005/08/27.

26 Joniau S, Bradshaw A, Esterman A, Carney AS. Reflux and laryngitis: a systematic review. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(5):686–92. Epub 2007/05/05.

27 Vaezi MF. Are there specific laryngeal signs for gastroesophageal reflux disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):723–4. Epub 2007/04/03.

28 Delahunty JE, Cherry J. Experimentally produced vocal cord granulomas. Laryngoscope. 1968;78(11):1941–7. Epub 1968/11/01.

29 Hicks DM, Ours TM, Abelson TI, Vaezi MF, Richter JE. The prevalence of hypopharynx findings associated with gastroesophageal reflux in normal volunteers. J Voice. 2002;16(4):564–79. Epub 2003/01/07.

30 Milstein CF, Charbel S, Hicks DM, Abelson TI, Richter JE, Vaezi MF. Prevalence of laryngeal irritation signs associated with reflux in asymptomatic volunteers: impact of endoscopic technique (rigid vs. flexible laryngoscope). Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2256–61. Epub 2005/12/22.

31 Vavricka SR, Storck CA, Wildi SM, Tutuian R, Wiegand N, Rousson V, et al. Limited diagnostic value of laryngopharyngeal lesions in patients with gastroesophageal reflux during routine upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(4):716–22. Epub 2007/04/03.

32 Vaezi MF, Richter JE, Stasney CR, Spiegel JR, Iannuzzi RA, Crawley JA, et al. Treatment of chronic posterior laryngitis with esomeprazole. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(2):254–60. Epub 2006/02/10.

33 Patel SM, Stason WB, Legedza A. The placebo effect in irritable bowel syndrome trials: A meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterol Motil 2005(17):332–40.

34 Kiljander TO, Salomaa ER, Hietanen EK, Terho EO. Gastroesophageal reflux in asthmatics: A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study with omeprazole. Chest. 1999;116(5):1257–64. Epub 1999/11/13.

35 Ahmed T, Vaezi MF. The role of pH monitoring in extraesophageal gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2005;15(2):319–31. Epub 2005/02/22.

36 Leggett JJ, Johnston BT, Mills M, Gamble J, Heaney LG. Prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux in difficult asthma: relationship to asthma outcome. Chest. 2005;127(4):1227–31. Epub 2005/04/12.

37 Sontag SJ, O’Connell S, Khandelwal S, Greenlee H, Schnell T, Nemchausky B, et al. Asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux: long term results of a randomized trial of medical and surgical antireflux therapies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98(5):987–99. Epub 2003/06/18.

38 Meier JH, McNally PR, Punja M, Freeman SR, Sudduth RH, Stocker N, et al. Does omeprazole (Prilosec) improve respiratory function in asthmatics with gastroesophageal reflux? A double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Dig Dis Sci. 1994;39(10):2127–33. Epub 1994/10/01.

39 Littner MR, Leung FW, Ballard ED, 2nd, Huang B, Samra NK. Effects of 24 weeks of lansoprazole therapy on asthma symptoms, exacerbations, quality of life, and pulmonary function in adult asthmatic patients with acid reflux symptoms. Chest. 2005;128(3):1128–35. Epub 2005/09/16.

40 Mastronarde JG, Anthonisen NR, Castro M, Holbrook JT, Leone FT, Teague WG, et al. Efficacy of esomeprazole for treatment of poorly controlled asthma. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(15):1487–99. Epub 2009/04/10.

41 Gibson PG, Powell H, Coughlan J, Wilson AJ, Hensley MJ, Abramson M, et al. Limited (information only) patient education programs for adults with asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002(2):CD001005. Epub 2002/06/22.

42 Kiljander TO, Harding SM, Field SK, Stein MR, Nelson HS, Ekelund J, et al. Effects of esomeprazole 40 mg twice daily on asthma: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173(10):1091–7. Epub 2005/12/17.

43 Fass R, Navarro-Rodriguez T. Noncardiac chest pain. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42(5):636–46. Epub 2008/03/28.

44 Fang J, Bjorkman D. A critical approach to noncardiac chest pain: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(4):958–68. Epub 2001/04/24.

45 Locke GR, 3rd, Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ, 3rd. Prevalence and clinical spectrum of gastroesophageal reflux: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(5):1448–56. Epub 1997/05/01.

46 Richter JE. Chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30(3 Suppl):S39–41. Epub 2000/04/25.

47 Ockene IS, Shay MJ, Alpert JS, Weiner BH, Dalen JE. Unexplained chest pain in patients with normal coronary arteriograms: a follow-up study of functional status. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(22):1249–52. Epub 1980/11/27.

48 Davies HA, Jones DB, Rhodes J, Newcombe RG. Angina-like esophageal pain: differentiation from cardiac pain by history. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1985;7(6):477–81. Epub 1985/12/01.

49 Mousavi S, Tosi J, Eskandarian R, Zahmatkesh M. Role of clinical presentation in diagnosing reflux-related non-cardiac chest pain. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(2):218–21. Epub 2007/02/14.

50 Wang WH, Huang JQ, Zheng GF, Wong WM, Lam SK, Karlberg J, et al. Is proton pump inhibitor testing an effective approach to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux disease in patients with noncardiac chest pain?: a meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(11):1222–8. Epub 2005/06/16.

51 Lacima G, Grande L, Pera M, Francino A, Ros E. Utility of ambulatory 24-hour esophageal pH and motility monitoring in noncardiac chest pain: report of 90 patients and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 2003;48(5):952–61. Epub 2003/05/30.

52 Hsia PC, Maher KA, Lewis JH, Cattau EL, Jr., Fleischer DE, Benjamin SB. Utility of upper endoscopy in the evaluation of noncardiac chest pain. Gastrointest Endosc. 1991;37(1):22–6. Epub 1991/01/01.

53 Frobert O, Funch-Jensen P, Jacobsen NO, Kruse A, Bagger JP. Upper endoscopy in patients with angina and normal coronary angiograms. Endoscopy. 1995;27(5):365–70. Epub 1995/06/01.

54 Bautista J, Fullerton H, Briseno M, Cui H, Fass R. The effect of an empirical trial of high-dose lansoprazole on symptom response of patients with non-cardiac chest pain – a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(10):1123–30. Epub 2004/05/15.

55 Dickman R, Mattek N, Holub J, Peters D, Fass R. Prevalence of upper gastrointestinal tract findings in patients with noncardiac chest pain versus those with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)-related symptoms: results from a national endoscopic database. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(6):1173–9. Epub 2007/03/24.

56 Achem SR, Kolts BE, MacMath T, Richter J, Mohr D, Burton L, et al. Effects of omeprazole versus placebo in treatment of noncardiac chest pain and gastroesophageal reflux. Dig Dis Sci. 1997;42(10):2138–45. Epub 1997/11/19.

57 Pandak WM, Arezo S, Everett S, Jesse R, DeCosta G, Crofts T, et al. Short course of omeprazole: a better first diagnostic approach to noncardiac chest pain than endoscopy, manometry, or 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;35(4):307–14. Epub 2002/09/28.

58 Fass R, Fennerty MB, Ofman JJ, Gralnek IM, Johnson C, Camargo E, et al. The clinical and economic value of a short course of omeprazole in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Gastroenterology. 1998;115(1):42–9. Epub 1998/07/03.

59 Ofman JJ, Gralnek IM, Udani J, Fennerty MB, Fass R. The cost-effectiveness of the omeprazole test in patients with noncardiac chest pain. Am J Med. 1999;107(3):219–27. Epub 1999/09/24.

Funding / potential competing interests: No financial support and no other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.