Figure 1

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers for item 6.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2011.13312

Contemporary organ donation and transplantation social representations are the result of a socio-historic evolution that emerged in the late 1960s and consolidated in the late 1980s, as the advent of immunosuppressant drugs transformed transplantation as the therapy of choice to treat terminal organ failures. During these years, the key discourses to solicit organ donation to the next-of-kin changed from contributing to the development of the transplant medicine into the rhetoric of the gift of life [1].

With the increasing occurrence of organ shortage in the late 1990s, several authors thought that financial incentives would improve organ donation rates and, therefore, fill the unbalance between the demand and the organs available for transplant medicine [2–5]. This line of argument was criticised arguing that an exchange of money for organs would violate the ethical rules of altruism and gratuity, decrease voluntary organ donation and increase the human body parts commodification phenomena [6–8].

The organ donation rates, in Switzerland, are different depending on the cultural and linguistic regions. In order to unify the legal framework and the practices from one county to another, a new Federal Act on transplantation came into force on the 1st of July 2007. The shift proved to be effective at improving transplantation procedures and the number of organs available for transplant medicine [9, 10].

In order to investigate the organ donation decision making process, a broad survey was lead from 2009 to 2010 in the French-speaking Vaud county. Questions about direct, indirect and non financial incentives, for both living and deceased organ donation, were addressed to inhabitants and physicians with the aim to assess peoples’ opinions and anticipate the further academic debate. The topics of altruism, commodification of body parts and the risk of exploitation of people in precarious financial conditions were also jointly explored.

Our main assumption is that there is room to promote organ donation whilst avoiding the exchange of money for body parts. In this context, incentives would be used to acknowledge the act of the organ donor.

In the next paragraphs, the methods used and the main results of this study will be presented following the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) guidelines [11].

Within this broad cross-sectional study we investigated organ donation and transplantation social perceptions of the French-speaking Vaud county inhabitants and physicians using a postal questionnaire. Among the different topics addressed, some questions investigated people’s opinions about the possibility to introduce incentives to acknowledge the organ donation act.

From 2007 to 2008, a multiple-choice questionnaire on organ donation and transplantation social perceptions was created jointly by the researchers of the Interdisciplinary Ethics Unit (Ethos) and the Health Psychology Research Centre (CerPSa) of the University of Lausanne. The form was designed on the basis of the literature review and with the help of collaborators from the Swiss foundation for research in social sciences (FORS). Its validity was checked using quantitative and qualitative procedures. Firstly, the questionnaire was administered to 123 students of the Faculty of Social and Political Sciences of the University of Lausanne during an academic class, and statistical analysis allowed us to check its reliability, stability and sensitivity. Secondly, ten people were invited to complete the questionnaire and participate in an interview during which they had the opportunity to make comments about it.

As a result of this process (Appendix 1 http://www.smw.ch/fileadmin/smw/pdf/Appendix/SMW.2011.13312_Appendix.pdf ), the questions 26 and 29 addressed the topic of living and deceased organ donation incentives, respectively. Their introduction was similar and seven possible answers were explained for each one of them. The incentive options proposed were determined on the basis of the literature review. Three categories were then defined during an inter-judges procedure (table 1 and 2). Respondents had to check “yes”, “no” or “I don't know” to each one of them.

Furthermore, in the second section of the questionnaire (Appendix 1), item 6 aimed at checking people’s opinions about the possibility to acknowledge the donors’ act in order to improve the organ donation rates (fig. 1). Items 11, 22 and 7 addressed the topics of altruism, commodification of the body parts and the exploitation of the poor, respectively (fig. 4, 5 and 6). For each item, respondents had to choose on a four point Likert scale from “I completely agree”, “I partially agree”, “I partially disagree” and “I completely disagree”. In an additional case, people could check “I don't know”.

In the last section of the survey, some questions concerned the socio-demographic situation of the respondents.

| Table 1: Categories of incentives to living organ donation (question 26, appendix 1). | |

| “If the government or a charity for the promotion of organ donation wished to reward the act of people donating a kidney or a part of their liver and you were one of them, which one of these options would you find appropriate to acknowledge your act?” | |

| a) I would like to have some additional days of holiday | Non financial |

| b) I would like the act of donation to be recalled during a formal occasion | |

| c) A waiting list exists in order to determine who will first receive an organ. I would like to be first on the list if ever I came to need an organ | |

| d) I would like some money to be given to a charity of my choice | |

| e) I would like to have my health insurance contributions reduced | Indirect financial incentives |

| f) I would like to have my taxes reduced | |

| g) I would like to receive some money | Direct financial incentives |

| Table 2: Categories of incentives to deceased organ donation (question 29, appendix 1): | |

| If the government or a charity for the promotion of organ donation wished to reward the act of people donating his organs after their death and you or your family were among them, which one of these options would you find appropriate to acknowledge your act? | |

| a) I would like the act of donation to be recalled during a formal occasion | Non financial |

| b) A waiting list exists in order to determine who will first receive an organ. I would like a member of my family to be first on the list if ever one of them came to need an organ | |

| c) I would like some money to be given to a charity of my choice or my families choice | |

| d) I would like to have my family health insurance contributions reduced | Indirect financial incentives |

| e) I would like to have my family taxes reduced | |

| f) I would like the burial expenses to be reimbursed | Direct financial incentives |

| g) I would like my family to receive some money | |

After the Institutional Review Board approval, the questionnaire was sent, together with a reply envelope, by post in early January 2010 to 3000 inhabitants and 1155 physicians of the Vaud French-speaking county. Lay people were chosen randomly from the lists given by the poll firm AZ Direct SA with respect to sex, age and the district inhabitant densities. Furthermore, the questionnaire was sent to physicians chosen from the members of the Vaud Society of Medicine (SVM) with regard to their specialised medical field. No reminders were sent subsequently to encourage people to answer.

Statistics were performed with the assistance of the Institute of Applied Mathematics and using PAW Statistics 18.0 software at the Health Psychology Research Centre (CerPSa) of the University of Lausanne. As the response-scales were mainly nominal and ordinal, the Chi-square test was used to make between-group comparisons. The Kolmogoroff-Smirnov test was used to determine when distributions were normal and the T-test or Mann-Whitney test were performed in consequence. The confidence interval (CI) was established at 95%.

From the 8th of January to the 26th of February 2010, we received 999 questionnaires. A total of 67 of them were removed from the pool because they were not complete. The final response rates of 19% (N = 556) for the inhabitants and of 33% (N = 376) for the physicians were considered satisfactory with regard to Swiss tendencies and to the method of administration [12, 13]. With regard to the socio-demographic characteristics (table 3), the two groups differed significantly on age (χ2(6) = 110.912, p <0.05), gender (Fischer’s exact test: p <0.05), number of adults and children in the family (respectively: χ2(5) = 21.948, p <0.05 and χ2(10) = 237.821, p <0.05) and on the total annual gross incomes (χ2(10) = 237.821, p <0.05).

Figure 1

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers for item 6.

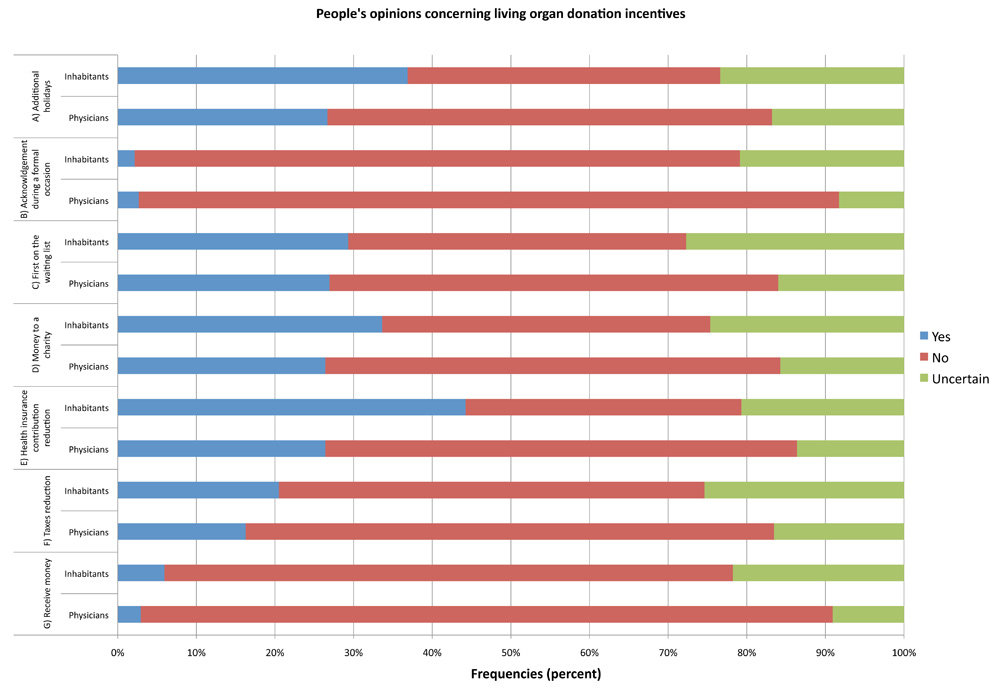

Figure 2

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers to the different living organ donation incentive propositions.

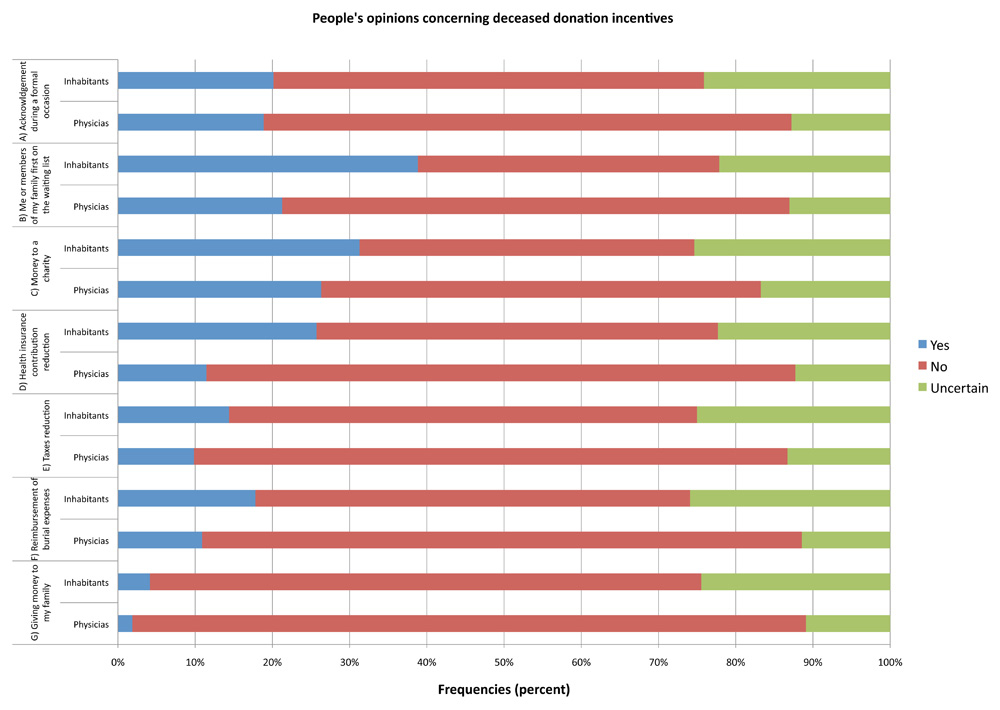

Figure 3

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers to the different deceased organ donation incentive propositions.

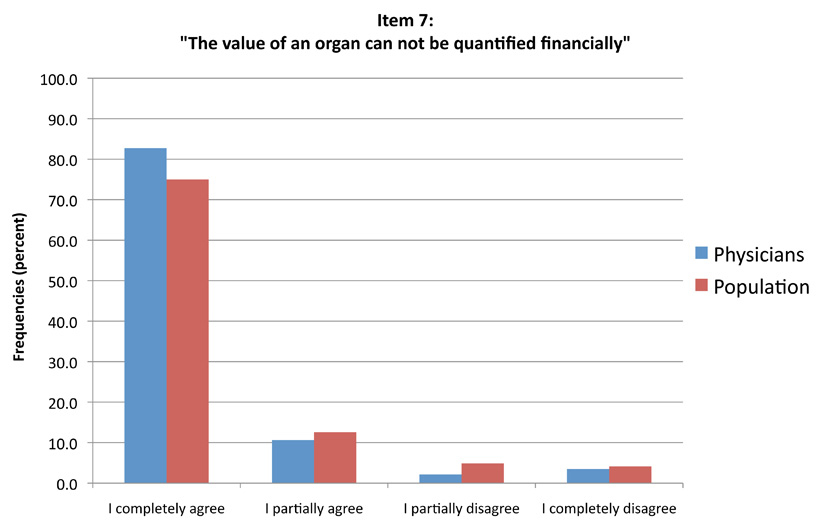

Figure 4

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers for item 7.

As the respondents represented 0.1% of the inhabitants and 13.9% of the physicians of the Vaud county and because we cannot guarantee the representativeness of the sample, all the results displayed below should be interpreted and generalised with caution.

Item 6: “Acknowledging the act of organ donors could increase organ donation rates” got a consensus from the two populations under investigation (fig. 1). Respondents from both populations agreed with it, without significant differences detected by the Chi-square (χ2(3) = 2.331, p = 0.507).

Nevertheless, for each incentive option displayed for living and deceased organ donation, the highest frequencies were observed on the answers “no”. In addition, 25% of the respondents declined to comment on this issue (they checked “I don't know” or did not check any case) (fig. 2 and 3). These findings suggest that the Vaud population as a whole does not consider the options to acknowledge the act of the living organ donors or, at best, they are ambivalent on this issue.

The answers recorded for items 7 (fig. 4) and 11 (fig. 5) allow us to make assumptions about the possible reasons of their reluctance: on the one hand, inhabitants agree with the fact that the value of an organ can’t be quantified financially (Mann-Whitney test: U = 93759.000, p <0.05). On the other hand, physicians unanimously considered that the organ donation is an altruistic act (χ2(3) = 26.097, p <0.05).

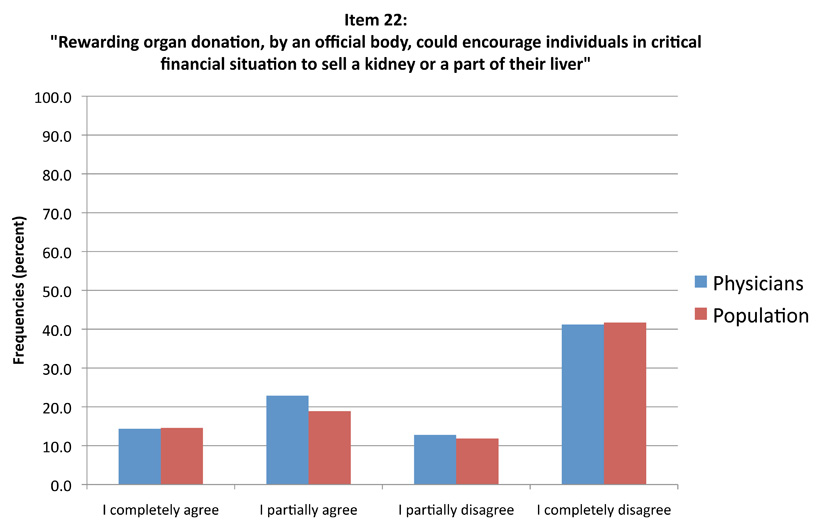

The statistical between-groups comparisons of the positive answers observed for question 26 about living donation (fig. 2) show that inhabitants more frequently chose the items A, C, D, E, F, and G than physicians (in all the cases, Fisher's exact test: p <0.05). Furthermore, the Chi-square test revealed that item B “I would like my action to be recalled in a formal occasion” seemed more attractive to physicians earning between 61’000 and 70’000 CHF than to physicians belonging to other salary classes (χ2(10) = 40.248, p <0.05). In opposition, the inhabitants of the same salary class preferred item E: “I would like my health insurance contributions to be reduced" (χ2(10) = 38.962, p <0.05). This trend was confirmed when comparing the households without children (χ2(10) = 30.038, p <0.05) and with just one child (χ2(10) = 21.744, p <0.05). Finally, inhabitants earning less than 40’000 CHF per year more frequently chose item G than others: “I would like to receive some money” (χ2(10) = 20.582, p <0.05), This result was confirmed when comparing the households with a child (χ2(10) = 30.124, p <0.05). Thus, with regard to the frequencies recorded for item 22 (fig. 6), with which both groups disagree (χ2(3) = 1.455, p = 0.693), we assume that the risk that people in precarious financial situations consider selling a kidney is underestimated by the respondents of both groups.

The second question about financial incentives concerned deceased organ donation (fig. 3). The statistical comparison of the distributions of the positive answers highlighted that differences exist with regard to the items B, C, D, E, F and G (in all the cases, Fisher’s exact test: p <0.05). The gap analysis to independence showed that inhabitants are more in favour than physicians of acknowledging the gesture of people donating their organs after their death.

Once more, the analysis of the total annual gross household incomes showed that people earning between 61’000 and 70’000 CHF preferred item D: “I would like my family health insurance contributions to be reduced” (χ2(10) = 22.362, p <0.05). This trend is confirmed when comparing households that have one or two children (respectively: χ2(9) = 20.728, p <0.05; and χ2(10) = 20.212, p <0.05). Furthermore, people earning less than 40’000 CHF or between 61’000 and 70’000 CHF per year more frequently chose items B: “I would like my family members to be first on the waiting list if ever one of them came to need an organ” (χ2(10) = 26.784, p <0.05) and F: “I would like the burial expenses to be reimbursed”(χ2(10) = 29.651, p <0.05). The influence of the number of children was tested with no significant results.

| Table 3: Socio-demographic characteristics of the sample. | ||

| Inhabitants | Physicians | |

| Age | 52.6 ± 15.9 years | 56.5 ± 10.6 years |

| Men in the sample | 50.5% | 76.5% |

| Native French-speakers | 86.2% | 91.2% |

| Family members | 1.9 ± 0.8 adults 0.7 ± 1 children | 1.9 ± 0.8 adults 1.4 ± 1.3 children |

| Average annual gross incomes | ||

| Less than 30000 | 5.20% | 0.30% |

| From 30000 to less than 50000 | 6.30% | 0.50% |

| From 41000 to less than 50000 | 6.30% | 1.10% |

| From 50000 to less than 60000 | 6.10% | 0.50% |

| From 60000 to less than 71000 | 9.00% | 1.90% |

| From 71000 to less than 80000 | 8.50% | 2.40% |

| From 80000 to less than 92000 | 8.50% | 4.00% |

| From 92000 to less than 107000 | 15.50% | 8.20% |

| From 107000 to less than 134000 | 11.20% | 18.10% |

| More than 134000 | 16.40% | 56.90% |

These results are interesting in several respects. It was shown that the respondents of both groups agreed with the need to acknowledge the act of donating organs in order to increase the national organ donation rates. Despite this fact, physicians and inhabitants are globally unfavourable of the incentives suggested for this questionnaire. These data are consistent with studies showing that a reward for organ donation is perceived as shocking or non pertinent by people [14, 15]. The reason for this reluctance could be the following: on the one hand, physicians seem to consider that organ donation is a selfless act. On the other hand, inhabitants do not think that the value of an organ can be quantified. The fact that physicians do not have unanimous opinions on this issue does not necessarily mean that they think that organs have an exchange value: it is possible that in the current Swiss context, where health costs are the subject of heated debates, physicians are more sensitive than inhabitants to the costs inherent to the transplant medicine.

Figure 5

Distribution of the physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers for item 11.

Figure 6

Physicians’ and inhabitants’ answers for item 22.

The analysis of the positive answers showed that indirect financial and non financial rewards were considered by both populations as the most pertinent way to reward living and deceased organ donation. People with modest incomes made an exception: the results showed that in fact they would prefer the direct financial ones. Thus, the suspicions of some experts suggesting that direct financial reward would attract the most needy people seem to be confirmed for this pool [16–19]. With regard to the frequencies recorded for item 22, this risk seems to be underestimated by both groups, The data analysis also highlighted that among people with incomes between 61,000 and 70,000 CHF the reduction in health insurance contributions is considered the most selected reward for both living and deceased donation. These results could be interpreted as a consequence of the increase in Switzerland, over the last few years, of health insurance contributions.

Nevertheless, because we cannot guarantee the representativeness of the sample, these results should be considered with caution.

The data collected by this survey suggest that the Vaud French-speaking population is opposed to a reward for living and deceased organ donation. The analysis of the positive answers in both groups suggests that indirect financial and non financial incentives are considered to be the most appropriate to encourage both living and deceased organ donation. The introduction of this kind of reward could avoid the commodification of body parts and the risk of exploitation of the poor. However, as altruism and gratuity seems to be key-values of organ donation, it is possible that the introduction of any kind of reward in the Swiss current context could tarnish the image of transplantation medicine. Yet, further studies are needed to evaluate if the introduction of indirect and non financial rewards would increase the organ donation rates or decrease voluntarism in the Vaud French-speaking province.

Acknowledgements: We thank the University of Lausanne and the 450th Foundation for funding the survey. We are also grateful to Prof. Jean-Philippe Antonietti, Prof. Boris Wernli, Mr. Oliver Lipps and Prof. Manuel Pascual for their advice during the creation of the questionnaire and its statistical analysis.

1 Moloney G, Walker I. Messiahs, pariahs, and donors: The development of social representations of organ transplants. J Theo Soc Behaviour. 2000;30(2):203–27.

2 Erin CA, Harris J. An ethical market in human organs. J Med Ethics. 2003;29(3):137–8.

3 Matas A, Schnitzler M. Payment for living donor (vendor) kidneys: a cost effectiveness analysis. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(2):216–21.

4 Matas A. The case for living kidney sales: rationale, objections and concerns. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(12):2007–17.

5 Daar AS. Paid organ procurement: Pragmatic and ethical viewpoints. Transplant Proc. 2004;36(7):1876–7.

6 Byrne MM, Thompson P. A positive analysis of financial incentives for organ donation. J Health Econ. 2001;20(1):69–83.

7 Delmonico FL, Arnold R, Scheper-Hughes N, Siminoff LA, Kahn J, Youngner, SJ. Ethical Incentives – not Payment – for organ donation. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(25):2002–5.

8 Joralemon D. Shifting ethics: Debating the incentives question in organ transplantation. J Med Ethics. 2001;27(1):30–5.

9 Uehelinger NB, Beyeler F, Weiss, J, Marti HP, Immer, FF. Organ transplantation in Switzerland: impact of the new transplantation law on cold ischemia time and organ transport. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(15-16):222–7.

10 Otth M, Rödder S, Immer FF, Marti HP. Organ donation in Switzerland: a survey on marginal or extended criteria donors (ECD) from 1998 to 2009. Swiss Med Wkly. 2011;141:w13230. doi: 10.4414/smw.2011.13230.

11 The STROBE checklist used in this paper is freely available on the websites of the Annals of Internal Medicine at http://www.annals.org/.

12 Bowling A. Mode of questionnaire administration can have serious effects on data quality. J Public Health. 2005;27(3):281–91.

13 Melkhop G, Becker R. Zur Wirkung monetärer Anreize auf die Rücklaufquote in postalischen Befragungen zu kriminellen Handlungen. Theoretische Überlegungen und empirische Befunde eines Methodenexperiments. Gesis. 2007;1(1):5–24.

14 Mayrhofer-Reinhartshuber D, Fitzgerald A, Benetka G, Fitzgerald R. Effects of financial incentives on the intention to consent to organ donation: A questionnaire survey. Transplant Proc. 2006;38(9):2756–60.

15 Schweda M, Schicktanz S. Public ideas and values concerning the commercialization of organ donation in European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(6):1129–36.

16 Rothman DJ, Rose E, Awaya T, et al. The Bellagio Task Force report on transplantation, bodily integrity, and the international traffic in organs. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(6):2739–45.

17 Brahams D. Kidney for sale by live donor. Lancet. 1989;1(8632):285–6.

18 Boulware LE, Troll MU, Wang NY, Powe NR. Public attitudes toward incentives for organ donation: a national study of different racial/ethnic and income groups. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(11):2774–85.

19 Kranenburg L, Schram A, Zuidema W, Weimar W, Hilhorst M, Hessing E, et al. Public survey of financial incentives for kidney donation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2008;23(3):1039–42.

Funding / potential competing interests: The University of Lausanne and the Foundation for the 450th birthday of the University of Lausanne founded this survey. The authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this paper.