Figure 1

Professional satisfaction of radiologists in Switzerland.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2011.13271

Professional satisfaction is a crucial factor for high quality medical service and patient care, for work motivation, for career choice, and for staying within the specialty. Furthermore, it can affect the radiologists’ personal health. There have been several studies on job and career satisfaction in physicians across various specialties [1–3], but only a few surveys have been published on radiologists’ professional satisfaction [4–6]. Recently, there were two papers published on professional satisfaction of radiologists in Europe, one of radiologists working in Germany [7] and the other of radiologists working in Italy [8]. Despite high levels of current satisfaction reported in all these studies, almost half the respondents claimed that they were less satisfied in their job than 5 years previously. The main factors for decreasing professional satisfaction were high workload, financial and time pressure. Therefore, it was reported that a relevant number of radiologists would not choose the specialty again. As reported in various studies [9–11], there is a tendency towards a shortage of radiologists in several countries, also in Switzerland. To keep or to enhance the attractiveness of radiology as a specialty, factors with an influence on professional satisfaction have to be identified and evaluated. In order to get more insight into the professional situation of radiology and radiologists, the Swiss Society of Radiology (SGR-SSR) supported the 2010 survey of their members.

The purpose of this study was (1) to evaluate the professional satisfaction of radiologists in Switzerland depending on person- and workplace-related factors, (2) to assess determinants of radiologists’ professional satisfaction, and (3) to explore the current level of enjoyment of radiology relative to the level of enjoyment five years previously.

The present study was part of the 2010 SGR-SSR survey. The professional characteristics of radiologists in Switzerland and factors on how to enhance the attractiveness of radiology for medical graduates as a specialty have been described in a previous paper [11]. In 2010, a questionnaire written in English (to have the same wording for all addressees) was mailed to 689 SGR-SSR members currently working in radiology in Switzerland. A total of 270 of the 689 radiologists took part in the study and returned the questionnaire, resulting in a response rate of 39.2%. Of the questionnaires returned, 8 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria for the study analyses (professionally active radiologist in Switzerland), and a further 8 respondents were excluded because they were 66 years and older and only worked part-time (less than 50%).

Ethical approval for the study was given by the board of the Swiss Society of Radiology.

Finally, the study sample comprised of 192 (75.6%) men and 62 (24.4%) women. Of the total number of SGR-SSR members (n = 729, including members currently working abroad), there are 545 (74.8%) male radiologists and 184 (25.2%) female radiologists. The mean age of the respondents was 45.9 years (SD 8.7 years, range 29–65 years). The distribution of the age ranges in our sample (<35 years: 13.3%, 36–45 years: 33.9%, 46–55 years: 37.8%, 56–65 years: 15.0%) was similar to the age ranges in the SGR-SSR members (<35 years: 16.0%, 36–45 years: 32.0%, 46–55 years: 34.2%, 56–65 years: 17.8%). In our sample, 70% came from the German-speaking part, 27% from the French-speaking part, and 3% from the Italian- and Roman-speaking part of Switzerland. In the SGR-SSR, there is only a distinction between German-speaking (546; 74.9%) and French-speaking (183; 25.1%) members.

The questionnaire used in this study, containing self-assessment scales, had already been used in the SwissMedCareer Survey [12], apart from items specifically for radiologists. The questionnaire proved to be a valid instrument in the previous assessments. The present survey included questions regarding the following topics:

Statistical analyses, including bivariate descriptive and inference statistics (t-test, F-test) as well as multivariate logistical regression, were carried out with SPSS for Windows, release 18 (PASW 18).

Outcome criterion: General job satisfaction during the past 4 weeks, originally rated on a 5- point Likert scale, was used as the outcome criterion in our logistic regression model, assigning persons not satisfied, rather unsatisfied, and rather satisfied to “low job satisfaction” (i.e. a negative outcome), and persons quite or very satisfied to “high job satisfaction”, and therefore a positive outcome.

Determinants: Table 1 lists those variables, which entered the logistic regression model as determinants, with the exception of partnership, children and grade of employment, which were not introduced into the model. Gender and language region are dichotomous variables per se, with female sex as well as French/Italian-speaking region (with respect to workplace) being treated as risk exposure (i.e. male sex and German-speaking region being protective exposures according to our definition). The 5-point categorical variable of workplace was dichotomised by defining private practice as no-risk exposition, against which each of the remaining work places (defined as risk expositions) were tested within the same logistic regression model. The majority of determinants are derived from continuous variables which, for their use in the logistic regression model, were dichotomised at the median, with 50% of participants rating lower than median being defined as at risk for low job satisfaction (bad outcome) and 50% of participants rating higher than median being “at risk” for high job satisfaction (good outcome). Table 1 shows the distributions (means and standard deviations) of professional satisfaction for the variables used as determinants in the logistic regression model as well as of those three variables that did not enter the model, as well as the results of bivariate group comparisons, and the logistical regression.

Results are expressed in terms of partial odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals, the contribution of the variables to the model being tested with Wald statistic and interpretation of very and highly significant results only. Our model correctly classifies 82.6% of the cases.

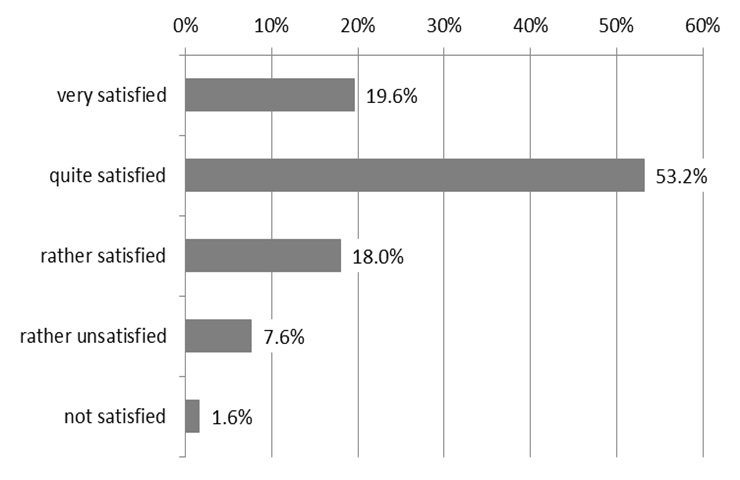

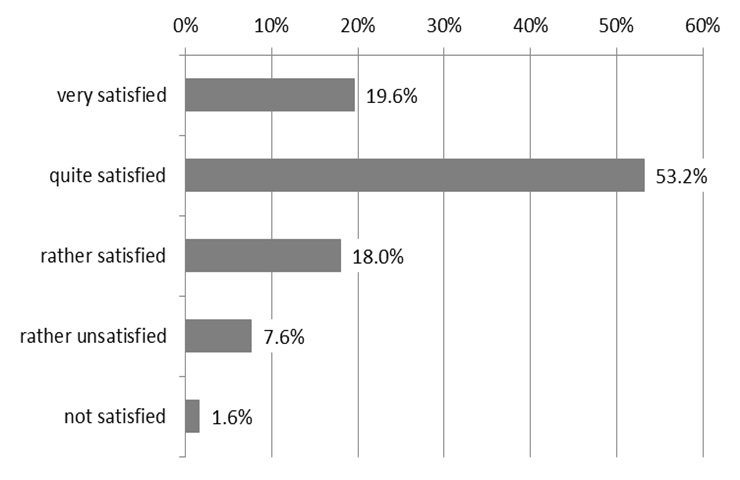

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the dependent outcome variable in its original form of a 5-point Likert scale.

Figure 1

Professional satisfaction of radiologists in Switzerland.

Figure 2

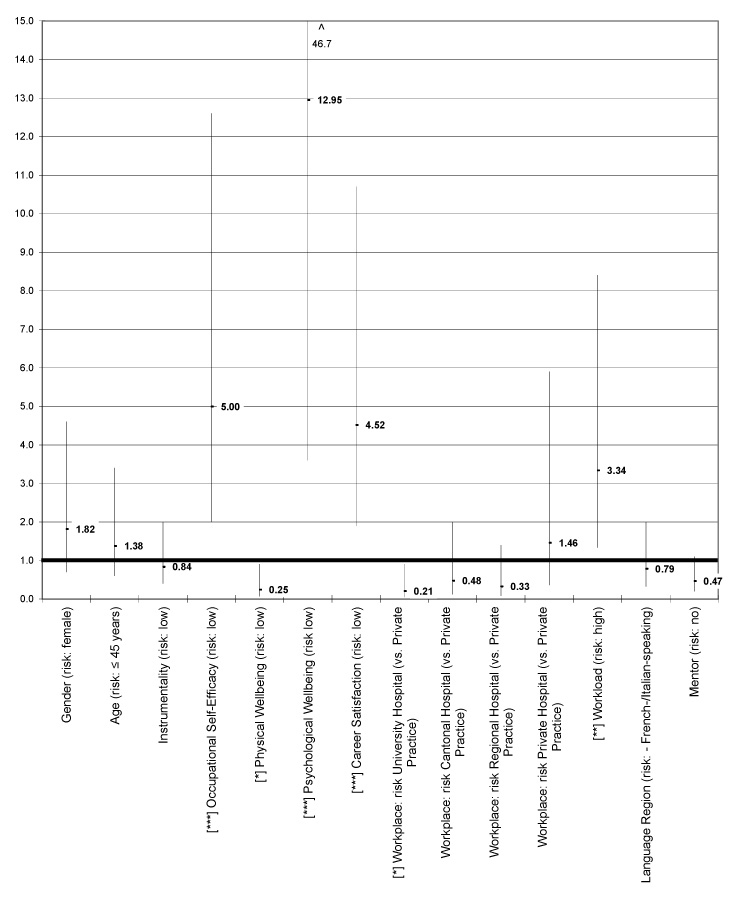

Logistic regression analysis of determinants of radiologists’ professional satisfaction.

Legend: Level of significance: *** p <0.001; ** p <0.01; * p <0.05 (Wald statistics). ^ The upper value of the confidence interval being 46.7 has been cut off.

One in five of the respondents were ‘very satisfied’, more than half of the participants were ‘quite satisfied’, less than twenty percent were ‘rather satisfied’, and less than ten percent were ‘rather or not satisfied’ in their job.

Bivariate group comparisons: Significantly higher professional satisfaction was reported by males, younger radiologists, and those with children. In terms of person-related factors, participants with high instrumentality, high occupational self-efficacy, high physical and psychological wellbeing showed higher job satisfaction. In terms of workplace-related factors, only career satisfaction and workload turned out to be significant factors. There was no significant difference in job satisfaction between radiologists with respect to workplace. Full-time or part-time employment, language region or mentoring did also not reveal significant differences in terms of job satisfaction.

A total of 68 (26.8%) of 254 respondents assessed their professional satisfaction as low, and 182 (71.7%) as high. Results of the logistic regression are shown in the right column of table 1 and illustrated in figure 2. The minority of the supposed risk factors for low job satisfaction turned out to be significant within the proposed regression model. Participants with low occupational self-efficacy were 5 times more at risk for low job satisfaction than participants with high occupational self-efficacy. Rather unexpected, low physical wellbeing turned out to be a significant protective factor against low job satisfaction, while low mental wellbeing, low career satisfaction and high workload increased the risk of low job satisfaction to a larger or smaller extent. Working in a university hospital turned out to be a significant protection factor against low job satisfaction when tested against private practice, while other types of medical workplace were neither risk nor protection factors. Gender, age, language region, and having or not having had a mentor during medical training turned out to be no determinants of job satisfaction within the model.

The participants reported whether they enjoyed radiology ‘much more’/’somewhat more’, ‘about the same’, ‘somewhat less’/’much less’ than five years ago. In table 2, the radiologists’ ratings depending on person- and workplace-related factors were listed.

Enjoyment of radiology relative to 5 years previously increased in 42.4% of the participants, in 39.1% it stayed about the same, and in 18.5% it decreased. The highest percentage of increased enjoyment was assessed in radiologists older than 45 years and in radiologists working at cantonal hospitals: over 50% enjoyed radiology more compared to five years previously. Remarkably, a quarter of participants working in private hospitals reported a decrease in enjoyment. Those radiologists who rated their person-related factors at a low level assessed lower levels of professional enjoyment relative to 5 years ago. In terms of career satisfaction, 80% of those who were highly satisfied declared to enjoy radiology more or about the same, however, one third of those with low career satisfaction reported that they enjoy radiology less than 5 years previously.

| Table 1: Professional satisfaction dependent on person- and workplace-related factors. | |||

| Professional satisfaction Mean (SD) | p (t-test) | OR (CI) Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Interval) | |

| Determinants in logistic regression model | |||

| Gender | 1.82 (0.72/4.61) | ||

| - Males | 3.88 (0.86) | 0.047 | |

| - Females | 3.62 (0.96) | ||

| Age | 1.38 (0.57/3.37) | ||

| - ≤45 years | 3.68 (0.86) | 0.023 | |

| - >45 years | 3.94 (0.90) | ||

| Instrumentality | 0.84 (0.36/1.96) | ||

| - High | 3.97 (0.87) | 0.007 | |

| - Low | 3.66 (0.89) | ||

| Occupational Self-Efficacy | 5.01 (2.0/12.57) | ||

| - High | 4.09 (0.79) | 0.000 | |

| - Low | 3.59 (0.91) | ||

| Physical Wellbeing | 0.25 (0.07/0.88) | ||

| - High | 3.93 (0.86) | 0.018 | |

| - Low | 3.65 (0.92) | ||

| Mental Wellbeing | 12.95 (3.59/46.67) | ||

| - High | 4.09 (0.76) | 0.000 | |

| - Low | 3.44 (0.93) | ||

| Career Satisfaction | 4.52 (1.91/10.71) | ||

| - High | 4.05 (0.73) | 0.000 | |

| - Low | 3.39 (1.00) | ||

| Workplace | |||

| - University Hospital | 3.73 (0.87) | 0.241 (F-test) | 0.21 (0.05/0.94) |

| - Cantonal Hospital | 3.80 (0.90) | 0.48 (0.12/1.96) | |

| - Regional Hospital | 3.73 (0.94) | 0.33 (0.08/1.44) | |

| - Private Hospital | 3.74 (0.91) | 1.46 (0.36/5.93) | |

| - Private Practice | 4.09 (0.84) | ||

| Workload | 3.34 (1.34/8.37) | ||

| - High | 3.72 (0.92) | 0.040 | |

| - Low | 3.97 (0.81) | ||

| Language Region | 0.79 (0.32/1.95) | ||

| - German-speaking | 3.78 (0.91) | 0.445 | |

| - French-/Italian-speaking | 3.87 (0.84) | ||

| Mentor | 0.47 (0.20/1.11) | ||

| - Yes | 3.77 (0.90) | 0.351 | |

| - No | 3.88 (0.88) | ||

| Further variables not in logistic regression | |||

| Partnership | |||

| - Yes | 3.85 (0.88) | 0.080 | |

| - No | 3.54 (1.00) | ||

| Children | |||

| - Yes | 3.90 (0.89) | 0.039 | |

| - No | 3.65 (0.87) | ||

| Employment | |||

| - Full-time | 3.83 (0.90) | 0.569 | |

| - Part-time | 3.76 (0.89) | ||

| Table 2: Level of enjoyment of radiology relative to 5 years previously dependent on person- and workplace-related factors (n = 238: 181 males, 57 females)1. | |||

| Enjoyment of radiology relative to 5 years previously | |||

| Much / somewhat more | About the same | Somewhat / much less | |

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| - Males | 76 (42.0) | 70 (38.7) | 35 (19.3) |

| - Females | 25 (43.9) | 23 (40.4) | 9 (15.8) |

| Age | |||

| - ≤45 years | 47 (35.6) | 57 (43.2) | 28 (21.2) |

| - >45 years | 54 (50.9) | 36 (34.0) | 16 (15.1) |

| Partnership | |||

| - yes | 91 (43.1) | 83 (39.3) | 37 (17.5) |

| - no | 10 (40.0) | 9 (36.0) | 6 (24.0) |

| Children | |||

| - yes | 68 (41.2) | 68 (41.2) | 29 (17.6) |

| - no | 32 (44.4) | 25 (34.7) | 15 (20.8) |

| Instrumentality | |||

| - high | 51 (43.2) | 48 (40.7) | 19 (16.1) |

| - low | 49 (41.5) | 45 (38.1) | 24 (20.3) |

| Occupational Self-Efficacy | |||

| - high | 48 (45.3) | 44 (41.5) | 14 (13.2) |

| - low | 52 (40.6) | 47 (35.7) | 29 (22.7) |

| Physical Wellbeing | |||

| - high | 56 (40.0) | 64 (45.7) | 20 (14.3) |

| - low | 44 (46.3) | 28 (29.5) | 23 (24.2) |

| Mental Wellbeing | |||

| - high | 63 (48.1) | 55 (42.0) | 13 (9.9) |

| - low | 36 (35.3) | 36 (35.3) | 30 (29.4) |

| Career Satisfaction | |||

| - high | 73 (47.1) | 67 (43.2) | 15 (9.7) |

| - low | 27 (32.9) | 26 (31.7) | 29 (35.4) |

| Workplace | |||

| - University Hospital | 22 (45.8) | 18 (37.5) | 8 (16.7) |

| - Cantonal Hospital | 28 (53.8) | 16 (30.8) | 8 (15.4) |

| - Regional Hospital | 19 (38.0) | 23 (46.0) | 8 (16.0) |

| - Private Hospital | 15 (37.5) | 15 (37.5) | 10 (25.0) |

| - Private Practice | 17 (37.0) | 19 (41.3) | 10 (21.7) |

| Workload | |||

| - high | 54 (46.2) | 43 (36.8) | 20 (17.1) |

| - low | 38 (45.8) | 30 (36.1) | 15 (18.1) |

| Employment | |||

| - Full-time | 71 (41.3) | 70 (40.7) | 31 (18.0) |

| - Part-time | 30 (46.9) | 21 (32.8) | 13 (20.3) |

| Language Region | |||

| - German-speaking | 72 (44.7) | 61 (37.9) | 28 (17.4) |

| - French-/Italian-speaking | 28 (38.4) | 29 (39.7) | 16 (21.9) |

| Mentor | |||

| - yes | 60 (43.5) | 56 (40.6) | 22 (15.9) |

| - no | 41 (41.0) | 37 (37.0) | 22 (22.0) |

| 1 N = 254 were included in the regression analysis. Only 238 participants answered the question on enjoyment of radiology relative to 5 years previously; 16 could not answer this question because they did not work in radiology 5 years ago | |||

The 2010 SGR-SSR survey aimed to assess the situation of radiology and the professional satisfaction of radiologists in Switzerland. As described in a previous paper [11], there is a tendency towards a shortage of radiologists in the forthcoming years. Firstly, a considerable number of radiologists are about to retire; secondly, although more women than men graduate from medical school, not as many women choose radiology as a specialty; and thirdly, the massive growth in the application of radiological imaging and image-guided interventions needs an increase in trained radiologists. The specialty choice of medical graduates depends on several factors. When actively working radiologists emanate high professional satisfaction, they serve as role models for the younger physician generation and might attract them to choose radiology. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to get more insight into the determinants of radiologists’ professional satisfaction.

Of the actively working radiologists in Switzerland participating in this study, 73% were assessed to be very/quite satisfied in their profession. In a recent German survey [7], 82% rated their job satisfaction at this level. In the 2003 US survey [4], 93% of the responding radiologists declared to be very/quite professionally satisfied. However, a survey conducted in Italy [8] revealed only 49% of the radiologists to be satisfied in their profession. The lower job satisfaction of radiologists in Switzerland compared to their colleagues in Germany and the U.S. may have several reasons. Possible reasons may be uncertainty with future reimbursement rates of insurances for radiological examinations as well as limited access to licenses for private practice. The restriction with regard to new licenses for private practice has lead to the fact that more radiologists working in private practice are now employees rather than partners. However, compared to the job satisfaction of physicians overall [2, 17], radiologists have higher levels of professional satisfaction. Reasons mentioned are a controllable lifestyle, the technology factor and the financial attractiveness [18, 19]. In a literature overview on job satisfaction among doctors [17], job satisfaction was reported to be highly influenced by the perceived professional autonomy defined as autonomy in terms of choice of diagnostic and therapeutic procedures. It can be assumed that radiologists rate this kind of professional autonomy as being high. Although most of the studies report a high percentage of professionally very satisfied radiologists, 72% of the German respondents would not choose radiology as a specialty any more [7]. The main reasons for this appraisal were the high workload, which was assessed as being much too high by two thirds of the study participants. In our study this issue was not addressed.

As far as we know, studies comparing job satisfaction of radiologists with other medical specialists are not reported in the literature. There are instead comparisons between physicians working in different institutions, of different career levels, and of different countries with different health care systems [3, 20, 21]. As job satisfaction is measured by different instruments, it is difficult to compare the reported results of the various studies.

Most studies have focused on work-related determinants of professional satisfaction [1, 3, 4, 7, 8]. High workload, inconvenient working hours, unsatisfying career perspectives, and time pressure were mentioned as main factors affecting job satisfaction. These factors contribute to perceived work-life conflicts which have a negative impact on professional satisfaction and health [22]. In our study we investigated person- as well as work-related determinants. High workload was a risk factor for low satisfaction. The two personal determinants ‘occupational self-efficacy’ and ‘psychological wellbeing’, however, were much stronger risk factors. Physicians who are self-confident can manage and cope with high demands and difficulties in their job. They are more efficient and thus more satisfied in their professional activities. Due to higher efficiency they might conduct more procedures per time. Furthermore, it is well-known that physicians who are in a good psychological condition are efficient at work and establish a good doctor-patient relationship. Both determinants contribute to job satisfaction. Another determinant that greatly affected the professional satisfaction in our regression model was the satisfaction with one’s career. As reported in our previous paper [11], female radiologists received less career support and mentoring, and rated their career satisfaction significantly lower than their male colleagues. It has been well described that mentoring and career support are key factors not only for career success, but also for career satisfaction [23, 24]. Taking the result of the regression model into account, training institutions and key radiologist-educators should provide structured and continuous career support and mentoring for the upcoming radiologist generation, but also for post-training radiologists.

Despite the objectively high workload and time pressure increasing in the last years [11, 25], 42% of our study participants were professionally more satisfied than five years previously, and only 19% enjoyed radiology less. The high percentage of radiologists assessing professional satisfaction as being higher than in previous years has to be interpreted cautiously. The phenomenon of socially desirable response behaviour might have played a role. The distribution of radiologists enjoying their profession more (37.5%) and those enjoying it less (24.8%) was similar in the German survey [7] to our study. In the US survey [4], 32% enjoyed radiology more, but 41% said they enjoyed it less. Medico-legal climate, workload, and reimbursement and financial pressures were the three most common reasons for decreased satisfaction. The reason for this increasing satisfaction of Swiss radiologists may be explained by the better recognition of radiologists among clinicians. Whereas radiologists were considered as “photographers” in previous years, today radiologists play a pivotal role in the diagnostic algorithms of most disease entities.

Concerns arise, however, that self-employed radiologists in private practice claim decreasing professional satisfaction, mainly due to high economic pressure. Radiology is a service oriented speciality. Time pressure is a crucial issue in modern radiology meeting the patients’ and the referring physicians’ needs as well as coping with economic factors: running a profitable practice within the given reimbursement rates. The main difference between working in a radiology institute affiliated to a hospital compared to working in private practice is the personal interaction between clinicians and radiologists. In private practice, there are usually less personal interactions between radiologists and clinicians. Most of the private radiology practices are separated from their referring physicians with regard to location. Radiology institutes in hospitals, situated within the health care institution, enable better communication between referring physicians, patients and radiologists.

Furthermore, the entrepreneurship risk of private radiologists may have an influence on professional satisfaction. Running a private radiology practice needs high financial investments. The unforeseeable future of reimbursement rates for medical services increases the financial pressure on private radiologists. These two factors (less personal interaction and increasing risk of entrepreneurship) are the most likely reasons for the lower satisfaction scores of radiologists working in private practice.

We acknowledge the following limitations. As the study was performed on the basis of data from the Swiss Society of Radiology, only radiologists belonging to the Society were included in the survey. However, it is estimated that nearly 95% of radiologists working in Switzerland are associated with this professional organisation. Another limitation refers to the response rate of the survey of 39% of all radiologists who had received the questionnaire. Reasons given by some of the addressed members of the SGR-SSR were not being sure about the anonymity of their answers because of requested report of gender, age, and working place. Our response rate, however, is typical of national survey studies of the members of physician societies [26]. As gender, age and language distribution of participants were not different from those of all SGR-SSR members, the results of this survey may be considered as representative.

Despite high workloads and time pressures, the radiologists’ professional satisfaction was relatively high. The majority even admitted an increase in enjoyment of radiology. As shown, person-related factors such as occupational self-efficacy played an important role for job satisfaction. Radiologists working in university hospitals assessed higher professional satisfaction compared to their colleagues in private practice. Considering the increasing interdisciplinary cooperation in diagnostic and therapeutic procedures established particularly in highly specialised hospitals such as university hospitals, radiologists get more recognition and acknowledgement by their clinical colleagues and also by patients. This, in combination with better career possibilities, might contribute to higher professional satisfaction of university hospital affiliated radiologists.

Acknowledgement: We thank the board of the SGR-SSR and in particular its secretary Christoph Luessi for their support in performing the study.

1 Hojat M, Kowitt B, Doria C, Gonnella JS. Career satisfaction and professional accomplishments. Med Educ. 2010;44:969–76.

2 Leigh J, Kravitz R, Schembri M, Samuels S, Mobley S. Physician career satisfaction across specialties. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1577–84.

3 Rosta J, Nylenna M, Aasland O. Job satisfaction among hospital doctors in Norway and Germany. A comparative study on national samples. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37(5):503–8.

4 Zafar HM, Lewis RS, Sunshine JH. Satisfaction of radiologists in the United States: a comparison between 2003 and 1995. Radiology. 2007;244(1):223–31.

5 Graham J, Ramirez A, Field S, Richards M. Job stress and satisfaction among clinical radiologists. Clinical Radiology. 2000;55(3):182–5.

6 Lim R, Pinto C. Work stress, satisfaction and burnout in New Zealnd radiologists: comparison of public and private practice in New Zealand. J Med Imaging Radiat Oncol. 2009;53(2):194–9.

7 Beitzel KI, Ertl L, Grosse C, Reiser M, Ertl-Wagner B. Berufszufriedenheit von Radiologen in Deutschland – aktueller Stand (Job Satisfaction of Radiologists in Germany – Status Quo). Fortschr Röntgenstr RöFo (Fortschritte auf dem Gebiet der Röntgenstrahlen und der bildgebenden Verfahren) 2011.

8 Magnavita N, Fileni A, Bergamaschi A. Satisfaction at work among radiologists. Radiol Med. 2009;114:1330–44.

9 Sunshine JH, Cypel YS, Schepps B. Diagnostic radiologists in 2000: basic characteristics, practices, and issues related to the radiologist shortage. AJR. 2002;178(2):291–301.

10 Sunshine JH, Maynard CD, Paros J, Forman HP. Update on the diagnostic radiologist shortage. AJR. 2004;182:301–5.

11 Buddeberg-Fischer B, Hoffmann A, Christen S, Weishaupt D, Kubik-Huch R. Specialising in radiology in Switzerland: Still attractive for medical school graduates? Eur J Radiology. 2011.

12 Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. How do physicians and their partners coordinate their careers and private lives? Swiss Med Wkly. 2011.

13 Alfermann D, Reigber D, Turan J. Androgynie, soziale Einstellungen und psychische Gesundheit: Zwei Untersuchungen an Frauen im Zeitvergleich. In Androgynie Vielfalt und Möglichkeiten. Eds Bock U, Alfermann D. Stuttgart: Metzler; 1999:142–55.

14 Abele AE, Stief M, Andrä MS. Zur ökonomischen Erfassung beruflicher Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen – Neukonstruktion einer BSW-Skala. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie. 2000;44:145–51.

15 Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Buddeberg C, Bauer G, Hämmig O, Knecht M, et al. The impact of gender and parenthood on physicians’ careers – professional and personal situation seven years after graduation. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10(40).

16 Daig I, Herschbach P, Lehmann A, Knoll N, Decker O. Gender and age differences in domain-specific life satisfaction and the impact of depressive and anxiety symptoms: a general population survey from Germany. Qual Life Res. 2009.

17 Gothe H, Köster AD, Storz P, et al. Arbeits- und Berufszufriedenheit von Ärzten. Eine Übersicht der internationalen Literatur. Dtsch Arztebl. 2007;104:A1394–A1399.

18 Dorsey ER, Jarjoura D, Rutecki GW. The influence of controllable lifestyle and sex on the specialty choices of graduating U.S. medical students, 1996–2003. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):791–6.

19 Gjerberg E. Gender differences in doctors’ preference – and gender differences in final specialisation. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:591–605.

20 O’Neill S, Thompson C, Kapp J, Worthington J, Graves K, Madlensky L. Job satisfaction in cancer prevention and control: a survey of the American Society of Preventive Oncology. Cancer Epidmiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19(8):2110–2.

21 Sabharwal M, Corle E. Faculty job satisfaction across gender and discipline. Soc Sci J. 2009;46:539–56.

22 Knecht M, Bauer G, Klaghofer R, Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Hämmig O. Work-life conflict and health among Swiss physicians – in comparison with other university graduates and with the general Swiss working population. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(w13063).

23 Stamm M, Buddeberg-Fischer B. The impact of mentoring during postgraduate training on doctors’ career success. Med Educ. 2011;45:488–96.

24 Buddeberg-Fischer B, Stamm M, Klaghofer R. Career paths in physicians’ postgraduate training – an eight-year follow-up study. Swiss Med Wkly. 2010;140(w13056).

25 Bhargavan M, Kaye AH, Forman HP, Sunshine JH. Workload of radiologists in United States in 2006–2007 and trends since 1991–1992. Radiology. 2009;252(2):458–67.

26 Kuerer HM, Eberlein TJ, Pollok RE, et al. Career satisfaction, practice patterns and burnout among surgical oncologists: report on the quality of life of members of the Society of Surgical Oncology. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3043–53.

Funding / potential competing interests: The study was supported in part by an unrestricted research grant by Bracco Switzerland.