Airborne transmission of respiratory viruses – Recognised in the 1940s, but then forgotten?

Kaspar Staub

In May 2022, an interesting article was published in the journal Indoor Air. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, authorities and experts had taken a relatively long time to recognise airborne transmission, especially via aerosols, as an important mode for the spread of this disease (and other infectious respiratory diseases). Valuable time may have been lost. In this article, the authors looked back in history to better understand this rejection of airborne transmission in general. Using a selected corpus, they showed that airborne transmission was thought for most of human history to be dominant but that, since the early 20th century, resistance has emerged to accepting that diseases are transmitted through the air. In their figure 2, the acceptance of airborne transmission of infectious diseases (including influenza) was at its lowest in the mid-20th century.

In response to that article, I would like to highlight a single example that suggests that even in the middle of the 20th century, the low point of acceptance of airborne transmission, public professional voices advocated precisely this view. When the number of influenza cases increased sharply internationally in late 1943 and early 1944, the Swiss health authorities expected an increase in cases in Switzerland. On January 8, 1944 (several months before the strong seasonal wave of influenza hit Switzerland), the federal authorities felt compelled to print a reminder about the nature of influenza in number 1 of their weekly bulletin for the attention of physicians, cantonal health authorities and the public (Löffler W. Grippe-Merkblatt. Bull des Eidgenössischen Gesundheitsamtes. 1944;1:4–9). This five-page factsheet was written by Professor Wilhelm Löffler (1887–1972), then Director of the Medical Clinic at the University Hospital in Zurich, and covered various aspects of the influenza virus and disease.

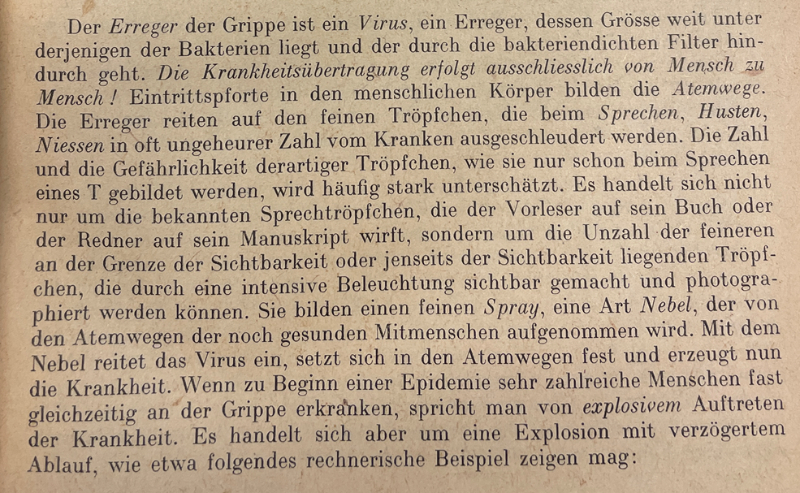

Regarding the pathogen and its transmission, the 1944 factsheet (figure 1, here translated into English) states on page 5: "The point of entry into the human body is the respiratory tract. The pathogens ride on the fine droplets expelled by the sick person when he speaks, coughs or sneezes, often in enormous numbers. The number and danger of these droplets is often underestimated. It is not only the well-known droplets that the reader throws on his book or the speaker on his manuscript, but also the countless finer droplets that lie on the border of visibility or beyond visibility and can be made visible and photographed by intensive illumination. They form a fine spray, a kind of fog, which is absorbed by the respiratory tract of healthy people.” On one hand, this represents the concept of droplets. On the other hand, it refers to additionally dangerous and much smaller, invisible and fog-like units. From today's viewpoint, this can be interpreted as suggesting aerosols and airborne transmission.

Figure 1: Extract from the influenza factsheet in bulletin number 1 of the Swiss Federal Health Office of 8 January 1944, reporting the pathogen and its airborne transmission, among other things.

With this example, I mean in no way to reject what I consider the generally correct conclusion of Jimenez et al., who followed general lines rather than individual opinions. I only want to note that the picture, especially in the mid-20th century, may have been more complex. Other opinions obviously accepted airborne transmission, but perhaps they have been simply forgotten over time. This forgetting of experiences over generations is precisely what seems to be a general problem in pandemic preparedness. Considering other strands of discourse on 20th-century airborne transmission, e.g. from authorities, daily newspapers or texts in other languages, may be worthwhile to better reflect the full variation of prevailing professional and public opinions at the time. Hopefully, someone will take the time and effort to deepen this important analysis to better understand the changes and nuances in this discussion.

PD Dr. Kaspar Staub, Institute of Evolutionary Medicine, University of Zurich, Winterthurerstrasse 190, CH-8057 Zurich, kaspar.staub[at]iem.uzh.ch