Clinical ethics during the COVID-19 pandemic in Switzerland

Caroline Brall, Rouven Porz, Ralf J. Jox

Introduction

Since March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has posed numerous challenges to healthcare systems worldwide. Debates on the use of contact tracing apps, development of and access to vaccines and management of limited resources in hospitals raised a wide range of ethical issues in the daily news. And in the daily routine of hospitals and nursing homes, diverse ethical matters – some familiar, some novel – were discussed. But what were the actual ethical challenges the COVID-19 pandemic posed to clinical ethics in Switzerland? What ethical issues were healthcare professionals confronted with? Were these the same issues that were being conveyed in the media, or did they have a different perception of the ethical challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic?

To answer these questions, we conducted a thematic content analysis of minutes of the COVID-19 video conferences on clinical ethics in Switzerland, which were held by healthcare professionals interested in clinical ethics, usually monthly. The minutes were provided for this purpose by the organisers of the video conferences.

With the analysis, we would like to elucidate which ethical issues occurred in the discourse during the COVID-19 pandemic in Swiss hospitals and how the participants of the video conferences perceived their professional ethical responsibilities during the pandemic situation. The findings from this analysis may further provide insights into whether and to what extent their perspective differs from that of the general population.

Background: The video conferences on clinical ethics issues during the pandemic

To respond to the challenges of the pandemic and to promote exchange among participants, regular video conferences were initiated at the beginning of the pandemic in March 2020, in which those working in or interested in clinical ethics in Switzerland could participate. The participants in the Zoom conferences represent a mixed collective of nurses, doctors, other health professionals such as speech therapists or physiotherapists, and ethicists from hospitals, universities and research institutions from all regions of Switzerland. In the following, we refer to the participants as healthcare professionals interested in clinical ethics. The aim of the video conferences was to promote mutual support between the participants, to exchange information and to anticipate emerging ethical challenges and initiate solutions. During the video conferences, some of the participants also reported on the status of their work in other national institutions tackling ethical issues in the pandemic response, such as the National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics (NCE), the Central Ethics Commission of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences and the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force advising the public authorities in the current COVID-19 crisis. Against this background, it is important to point out that the content of the video conferences does not represent actual clinical practice but provides valuable insight into how the participants perceived the challenges in their respective institutions. The number of participants varied between 14 and 47 people. The video conferences were recorded and minutes sent to participants. Between March 2020 and January 2022, 28 video conferences took place, mostly monthly. For our analysis, 27 sets of minutes were available. We analysed the available minutes using a qualitative, thematic content analysis according to Mayring (2000). For this purpose, the three authors read the minutes, summarised the mentioned topics, categorised them inductively and compared them. In this way, the central themes of the discourse could be identified and interpreted.

The central topics of the discourse on challenges in clinical ethics during the pandemic in Switzerland

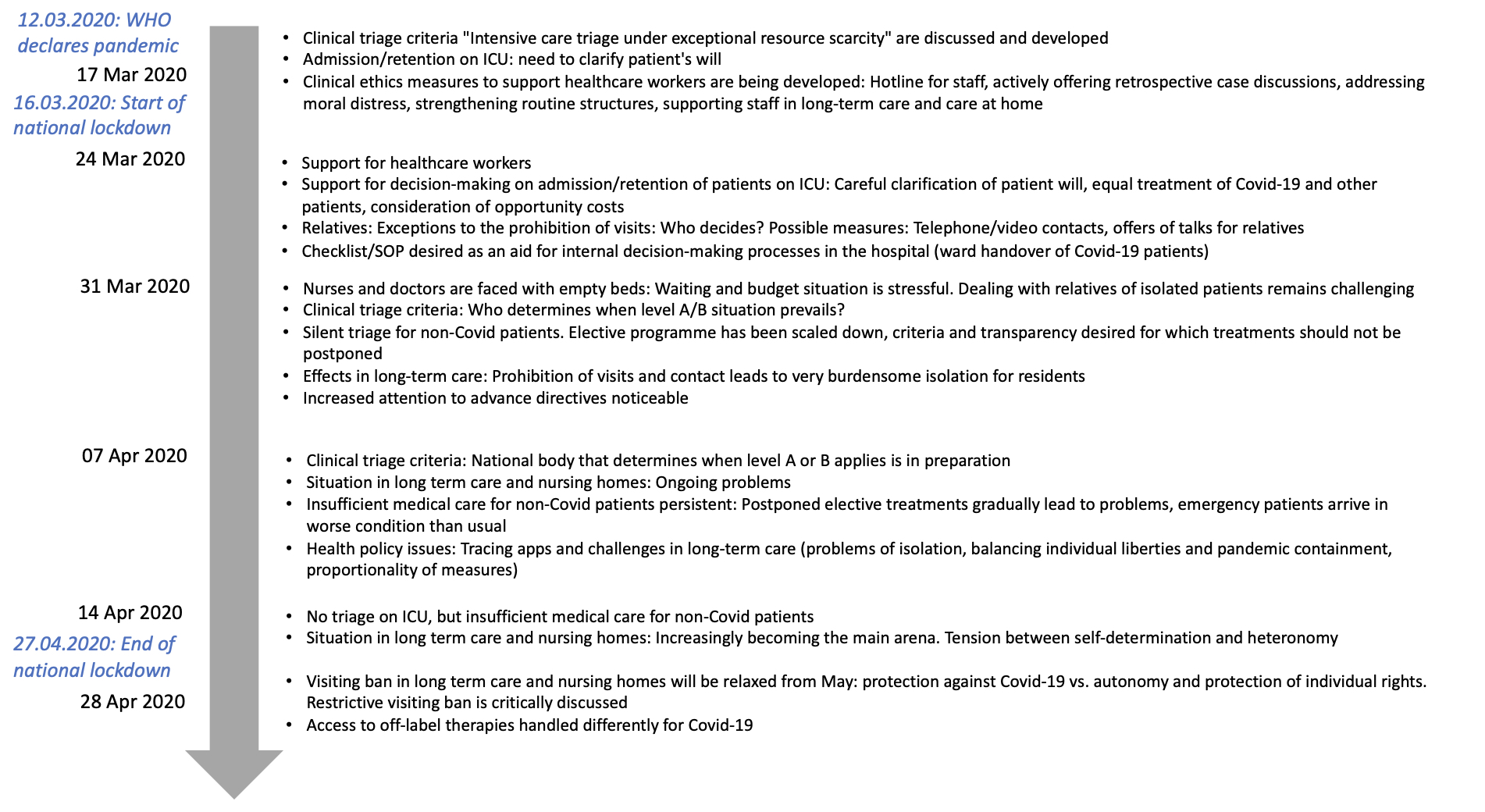

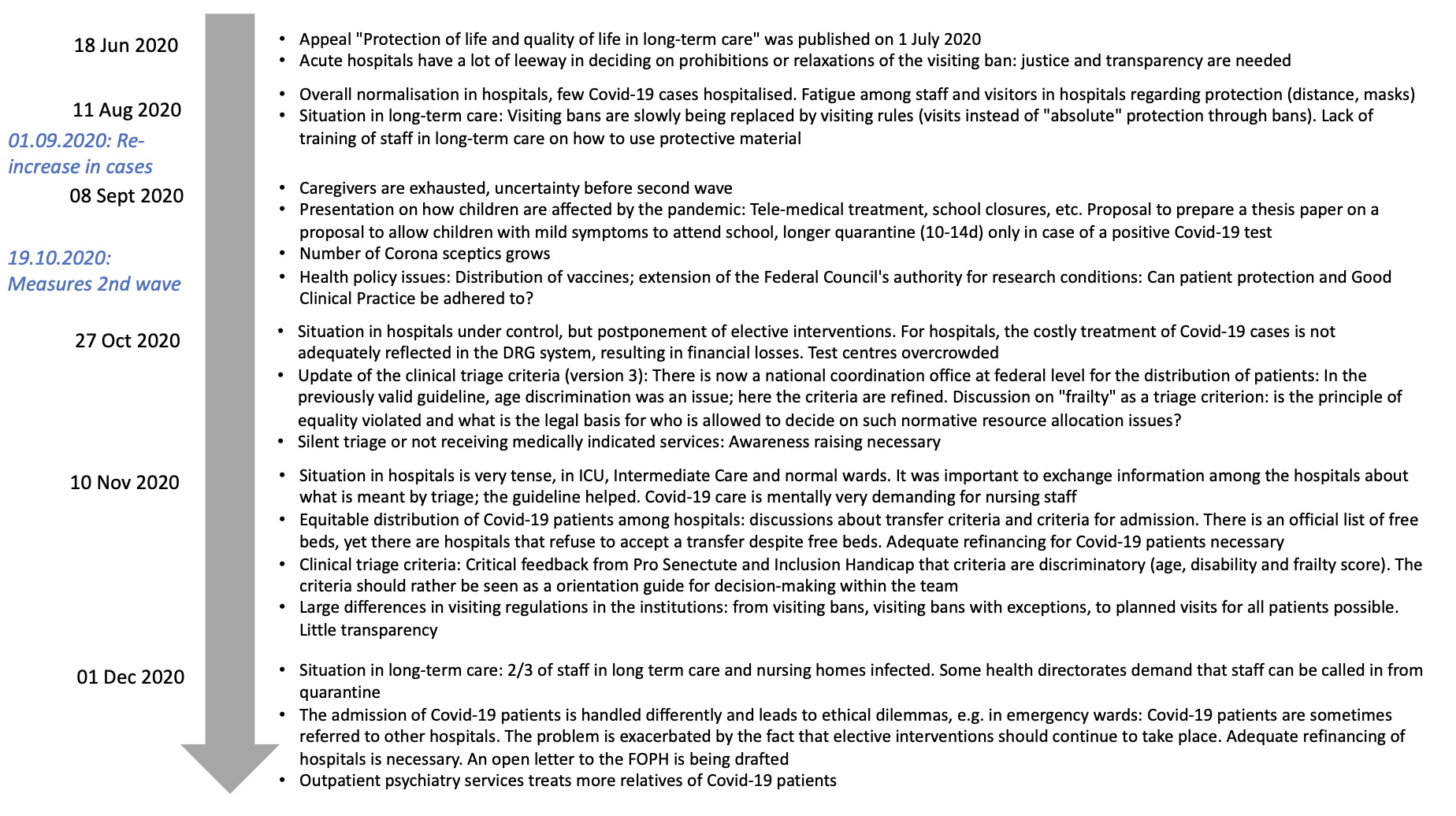

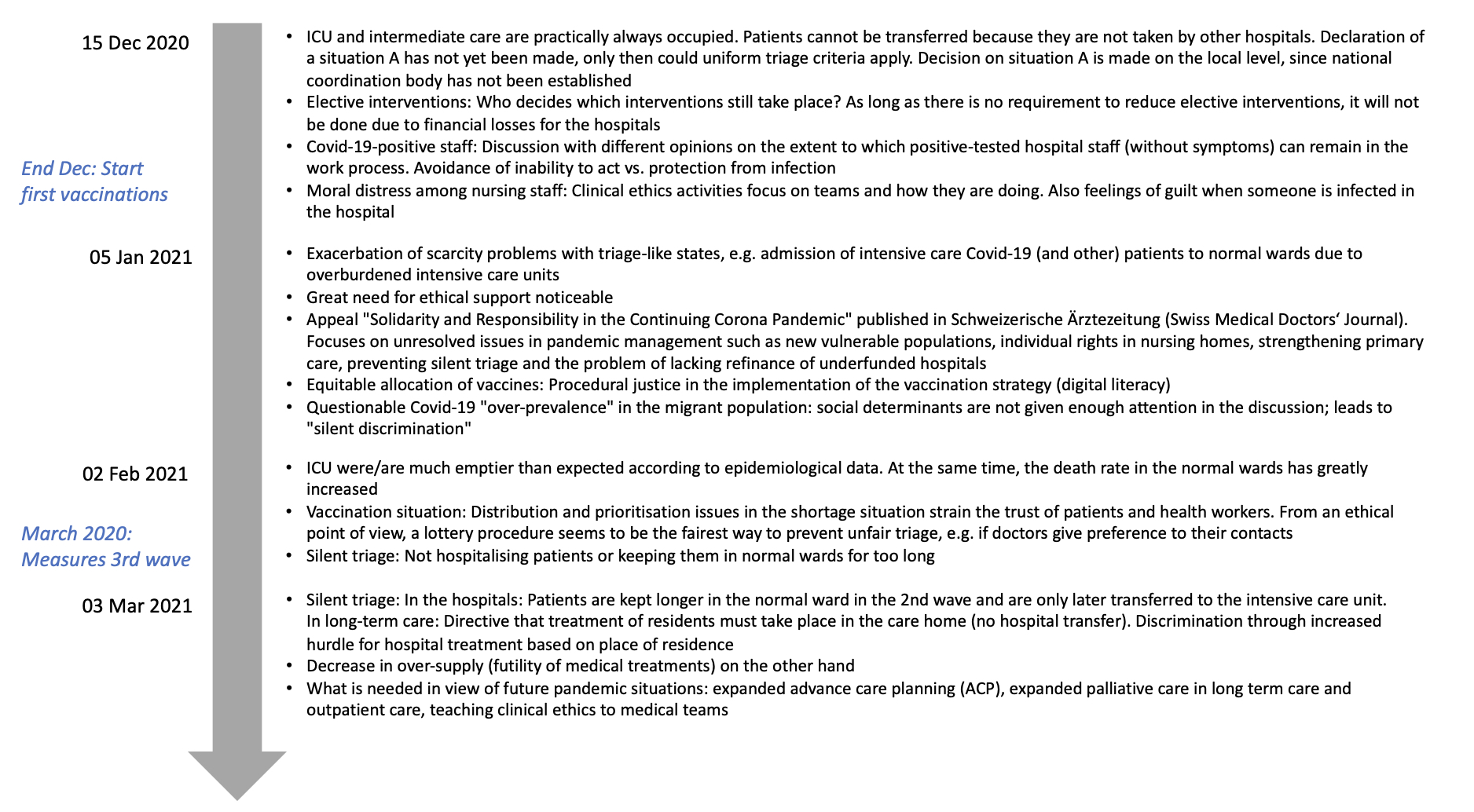

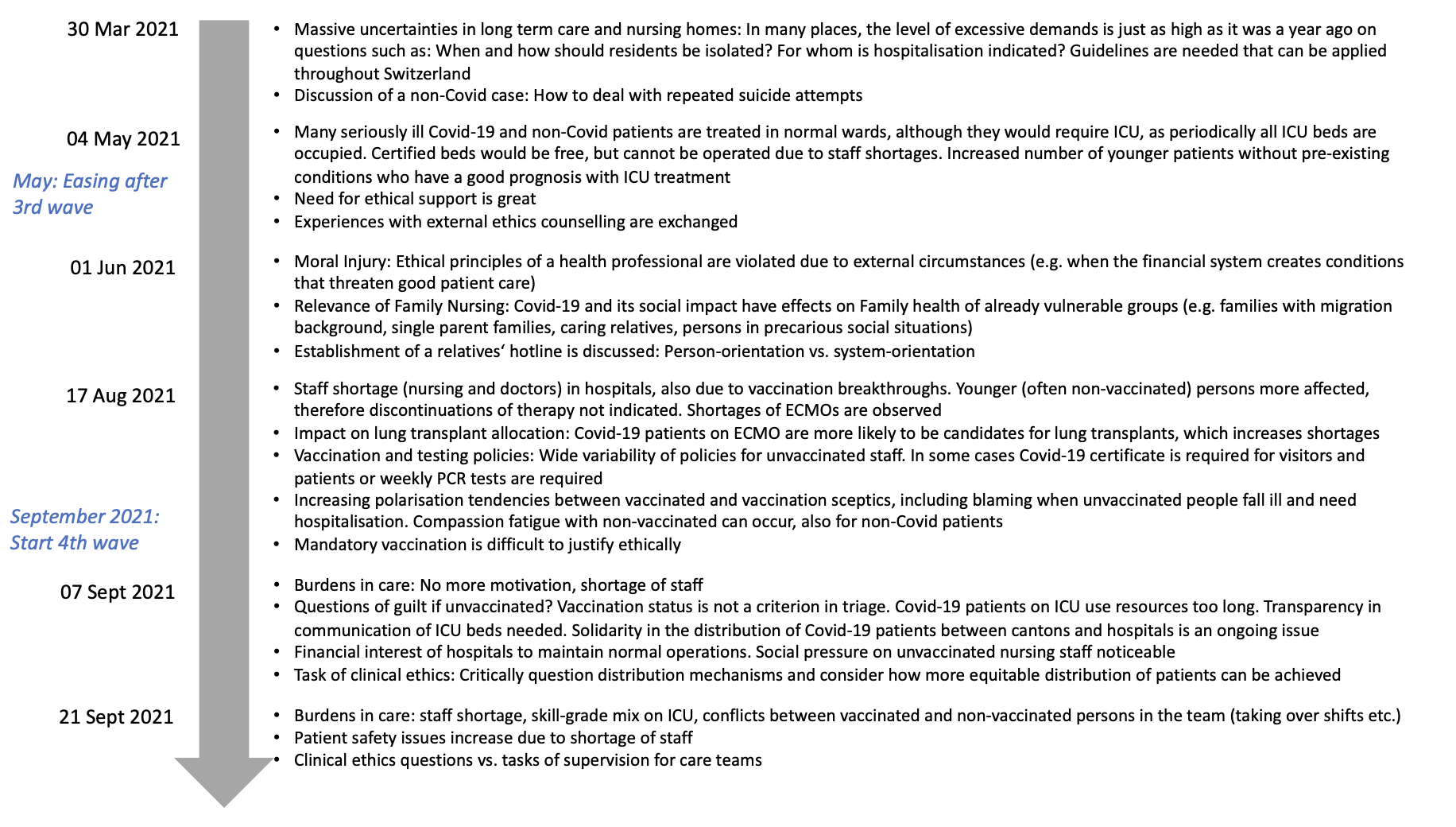

Certain topics were repeatedly discussed during the discourse of the video conferences on clinical ethics. Particular focus was placed on the triage guidelines of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences and the Swiss Society for Intensive Care Medicine, the continuing challenges in long-term care facilities and nursing homes, as well as distressing situations in medical care teams. Overall, the discussions during these video conferences drew attention to vulnerable groups. Health policy measures, such as closures or vaccination campaigns, were addressed and updates were exchanged by representatives of the respective national institutions on medical ethics issues and their ethical aspects were discussed when relevant. Figure 1 shows an overview of the topics discussed during the 27 video conferences held between March 2020 and January 2022. The central topics are outlined in the following sections.

Figure 1: Overview of the topics of the video conferences on clinical ethics in Switzerland, by date.

Discussions about possible triage and its criteria in Swiss hospitals

Discussions on possible triage were already considered important in mid-March 2020 to prepare for the potential upcoming shortages of beds and ventilators in Swiss hospitals. To this end, the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, together with the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine, developed an addendum to the existing guideline from 2013 on clinical criteria for triage for intensive care measures (chapter 9.3 of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences guideline on Intensive Care Measures). A challenge for implementation was that nobody had been formally designated to determine which guideline level (level A: places for intensive care are still available but very limited; level B: no places for intensive care are available) to assign to the prevailing critical capacity situation and thus activate/deactivate application of the guideline. Initially, the Swiss Academy of Medical Science and the Swiss Society of Intensive Care Medicine suggested that the determination should not be made at national level, as the critical capacity situation in the hospitals differed regionally. It was therefore advised to decide on the A/B situation on a regional or cantonal level. However, a national coordination body for the distribution of patients based at the federal level was established in October 2020. Even though the application of triage criteria had not been officially activated, “silent triage” of non-COVID-19 patients was an anticipated topic during the video conferences especially at the beginning of the pandemic. Here, the perceived risk was underuse or omission of necessary services for non-COVID-19 patients in the healthcare setting in general or in intensive care treatment. The reasons for this were complex: elective procedures were being postponed and in some cases outpatient consultations were closed at the beginning of the pandemic. During this phase, so-called “self-triage” by patients was also observed: patients did not attend follow-up appointments or avoided emergency consultations for fear of infection or in order to not burden the healthcare system. Regarding the postponement of elective procedures, greater transparency was desired from an ethical point of view as to which treatments were affected, and the development of applicable criteria for the postponement of elective procedures was identified as necessary. The Central Ethics Commission of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences has since published a corresponding statement. Due to the thematic proximity of the discussion recorded in the minutes and the contents of the Central Ethics Commission statement, it can be assumed that the discussions during the video conferences were taken up by the Central Ethics Commission members. In these discussions, the participants of the video conferences emphasised particularly that COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 patients must be treated equally.

Visiting and contact bans in long-term care and nursing homes

The impact of visiting and contact bans in long-term care was discussed during the video conferences over the course of four pandemic waves. The visiting and contact bans led to burdensome situations for the residents in many long-term care and nursing homes, which were still not adequately resolved in October 2021 and were handled individually by the institutions according to vastly different criteria and processes. The professionals interested in clinical ethics therefore pointed out that management teams of long-term care and nursing homes had to be made more aware of the imperative to ensure that the fundamental rights of residents were being respected. In addition, they emphasised the need to strike a fair balance between protecting against COVID-19 and preserving the right to social interaction. Assessing cases individually instead of sticking to inflexible policies was seen as preferable.

Distressing situations in medical care teams

The third central topic discussed by participants during the video conferences was the ongoing distressing situations in medical care teams during the entire pandemic period. At the end of March 2020 in the German-speaking regions the “wait for the wave” burdened the care teams. “Moral distress” gained increasing importance in the course of the pandemic. Moral distress describes the distress experienced in a situation, as a health worker for example, where one has clear moral obligations but cannot act on them due to institutional or other external constraints. An example of this is ensuring adequate care for patients when resources are limited, a situation exacerbated in pandemics. In addition, changes to treatment routines and greater difficulties in planning and caring for high-risk patients also led to interprofessional differences and team conflicts and had emotional, physical and professional repercussions on a personal level. The participants in the video conferences perceived it as a central task of clinical ethics to support nurses, physicians and other hospital staff in coping with stressful situations, e.g. by implementing a hotline for staff, actively offering retrospective case discussions and strengthening routine structures for new procedures.

Clinical ethics and its professionalisation in Switzerland

During the video conferences on clinical ethics, a question that came up repeatedly was which tasks the discipline of clinical ethics in Switzerland actually has in pandemic situations and how it should position and organise itself in the future. The regular video conferences of professionals interested in clinical ethics in Switzerland were seen as mutual support in everyday life, as a forum for the exchange of experiences across different institutions, as an interface between practice and other ethics advisory bodies (e.g. the National Advisory Commission on Biomedical Ethics, the Central Ethics Commission of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences, the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force, etc), as well as a forum for discussing how clinical ethics could be developed. Standardisation and certification of training in clinical ethics were identified as other key tasks for the future. The topics discussed during the video conferences corresponded partially with the issues highlighted in the media and by the general public but were analysed in depth during the video conferences on clinical ethics, where solutions were developed and proposed. The video conferences therefore contributed to directing attention to ethical topics that were relevant to practice but not (yet) the focus of public debate. The group’s publications drew public attention to relevant issues, such as on life protection and quality of life in long-term care or solidarity and responsibility during the pandemic. Overall, the pandemic represented an opportunity for clinical ethics to build national networks to discuss specific challenges, but also to transparently demonstrate how the discipline of ethics can provide support in hospitals, long-term care facilities and nursing homes. While clinical ethics were indispensable in overcoming the immense challenges of the pandemic, it remains crucial to assess how the lessons learned can be sustainably transferred to the post-pandemic period.

Limitations

The analysis of the minutes provides insight into the ethical challenges faced in Swiss hospitals and care facilities during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it also has limitations. Due to the heterogeneity of the participants in the video conferences and their different backgrounds (clinical ethicists working in hospitals, healthcare professionals from diverse disciplines interested in ethics, etc), the discussions encompassed a wide range of viewpoints. The discussions often involved more brainstorming and exchange of experiences than in-depth ethical deliberations, and this can be explained by the exceptional pandemic situation. Furthermore, the minutes were written by different participants and, depending on the topic and the participant, the discussion was documented in varying depth, sometimes only as key words or essential aspects. Chat messages between participants were only used by the participants during the videoconferences, but were not recorded and hence not included in the analysis. This analysis therefore does not seek to be representative yet it offers valuable insight into the participants’ discourse and into the clinical ethics challenges posed during the pandemic in Switzerland.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Sibylle Ackermann, Manya Hendriks, Tanja Krones, Settimio Monteverde and Tatjana Weidmann-Hügle (organisers of the video conferences on clinical ethics) for providing the minutes. We also thank them as well as Samia Hurst and Markus Hofer for their helpful comments on our draft.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The study is part of the research project “Ethics, pandemic preparedness and policy responses: novel viruses, novel challenges. The case of COVID-19 revisited — a pilot study”, which is funded by the Käthe-Zingg-Schwichtenberg-Fonds of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences.

Caroline Brall, Ethics and Policy Lab, Multidisciplinary Center for Infectious Diseases, University of Bern, Switzerland, and Institute of Philosophy, University of Bern, Switzerland

caroline.brall[at]unibe.ch

Rouven Porz, Medical Ethics, Medical Directorate, Inselspital, University Hospital of Bern, Insel Gruppe, Bern, Switzerland

Ralf J. Jox, Institute of Humanities in Medicine, Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland