The quality of public communication during COVID-19: symptoms of a wider malaise

Annegret Hannawa

We like accurate weather forecasts. We purchase insurance plans that use certainty as a currency. We want to be able to predict the next turn of events. If we can’t have that, then we experience discomforting stress that we want to escape at any cost [1, 2].

Tolerating uncertainty goes against our human nature. At the same time, the past three years have kept us hostage in an uncertainty roller-coaster that seems to have gotten caught up in a loop. Strike words like “climate change,” “COVID” and “energy crisis” sneak up on us at each corner, again and again startling us back into constant states of distress.

How do we react to this?

“Uncertainty reduction” is a well-researched paradigm in communication science that predicts and explains our reactions [1, 2]. Numerous studies have shown that states of uncertainty drive us into information-seeking behaviour, through which we want to reestablish a comforting degree of certainty – be it through passive observation, by active communication with others, or by extracting information from online resources [3]. In other words, our communication is a critically important process in uncertainty-ridden situations, as it operates the switch that will make things either stay on track or derail.

Although this communication phenomenon has been well-studied and understood for many years, all that knowledge suddenly seems to have “vanished” from Earth during COVID-19. Our communication with each other ran astray as if it went on autopilot. People started to aggress against each other [4], mobilising emotional hurricanes with pointed fingers that instantly froze discussions into ice. Marriages broke. Friendships fell apart. The ever-widening chasm between “compliers” and “deniers” ripped anyone in between into a merciless abyss.

No one seemed to understand why this was happening. We had lost control over our communication – over the one thing that is most characteristic of our human nature [5].

Sadly, the driving force that feeds into this destructive social pattern continues until today, and it remains uninterrupted by any scientific interventions. While conspiratorial storytelling continues to seize the power of digital pathways to harvest successes by focusing on certainty-establishing relief, messages by governments and the news media keep pouring salt into the “uncertainty” wound, keeping us trapped there. In the meantime, many more chasms have ripped open. The greatest of all is the one between communication science and our real-life communication with each other. Many studies have now loudly proclaimed the “do-nots” that could guard us against further conspiratorial inflammations and societal fragmentation [6–9], but exactly those kinds of practices continue to dominate our communications about uncertainty-inducing events. We are now even witnessing spill-over effects into newly emerging uncertainty situations, such as the global energy crisis that hovers over our heads like a dark cloud that is ready to burst at any moment.

This chasm needs to close – rapidly.

COVID-19 has hit us like a tsunami, with recurring waves of destruction leaving us with even more chaotic conditions each time. Governments and citizens were equally overwhelmed by the situation. Everyone did their best at the time, trying to keep their heads together and the crisis under control. No one could have known the ripping effect our communication was going to have on the crisis down the road. But now we know. It is for this reason that I decided to write this evidence-based op-ed piece as a communication science recipe for how to engage in safer communication in similar future crises.

Closing the chasm: Five lessons learned from COVID-19

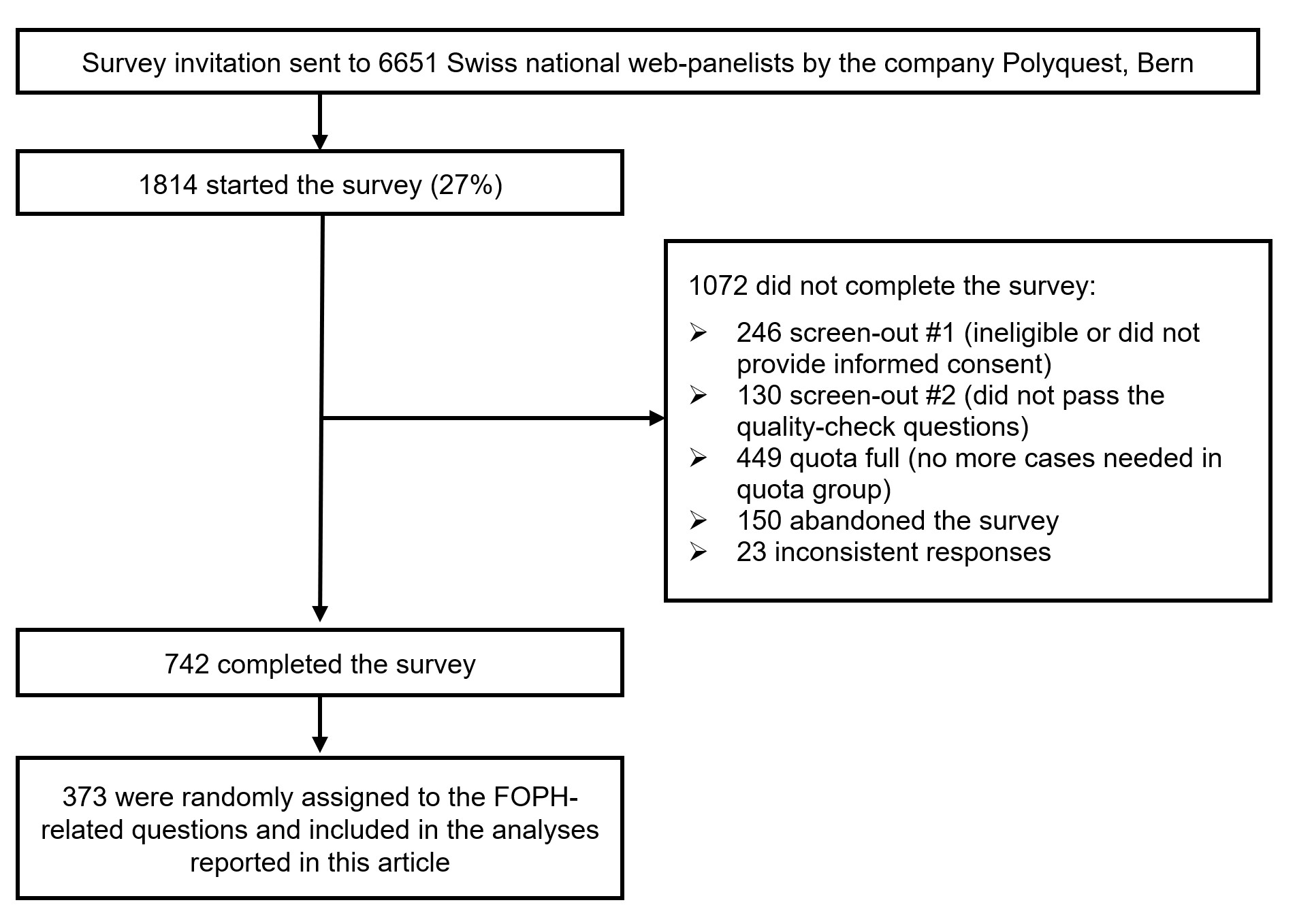

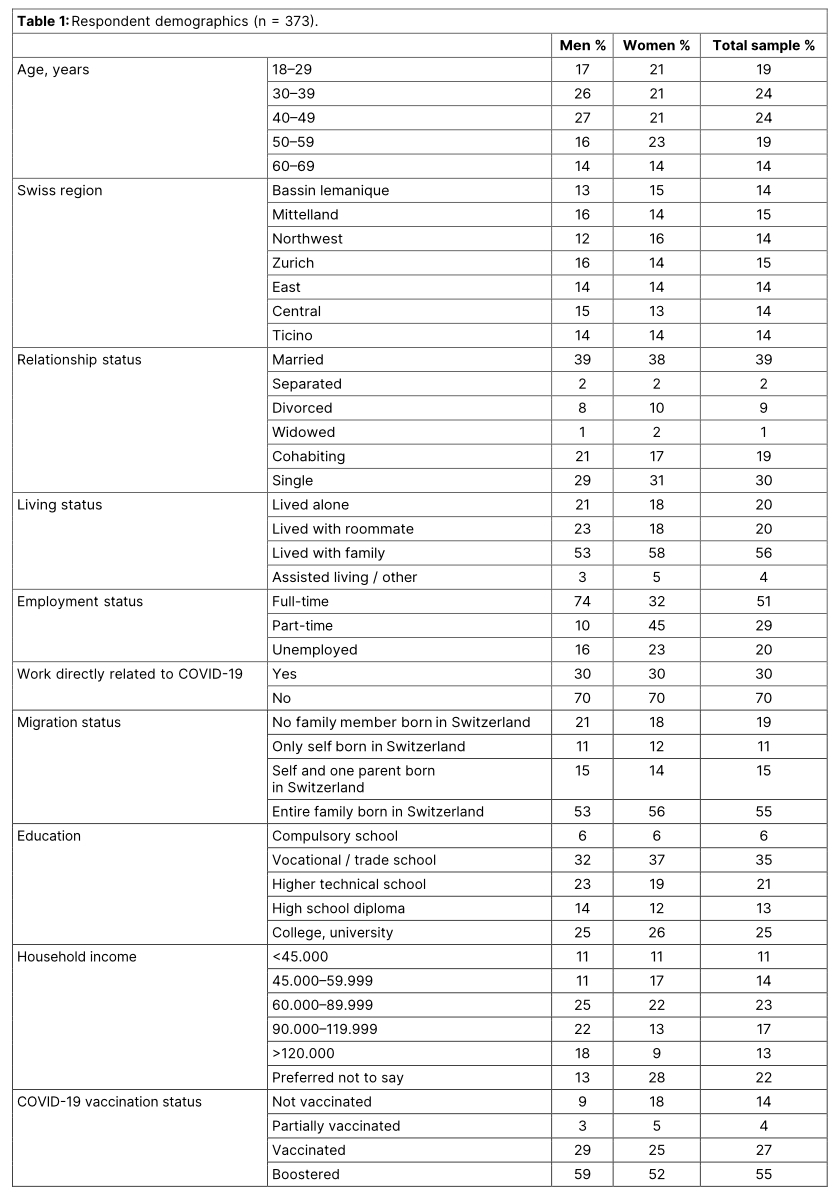

In February 2022, I led a national “COM-COVID” investigation [10] in Switzerland to measure how communication by the Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH) about COVID-19 affected the Swiss population during the first two years of the pandemic (fig. 1, table 1).

Figure 1. Recruitment process for the COM-COVID survey.

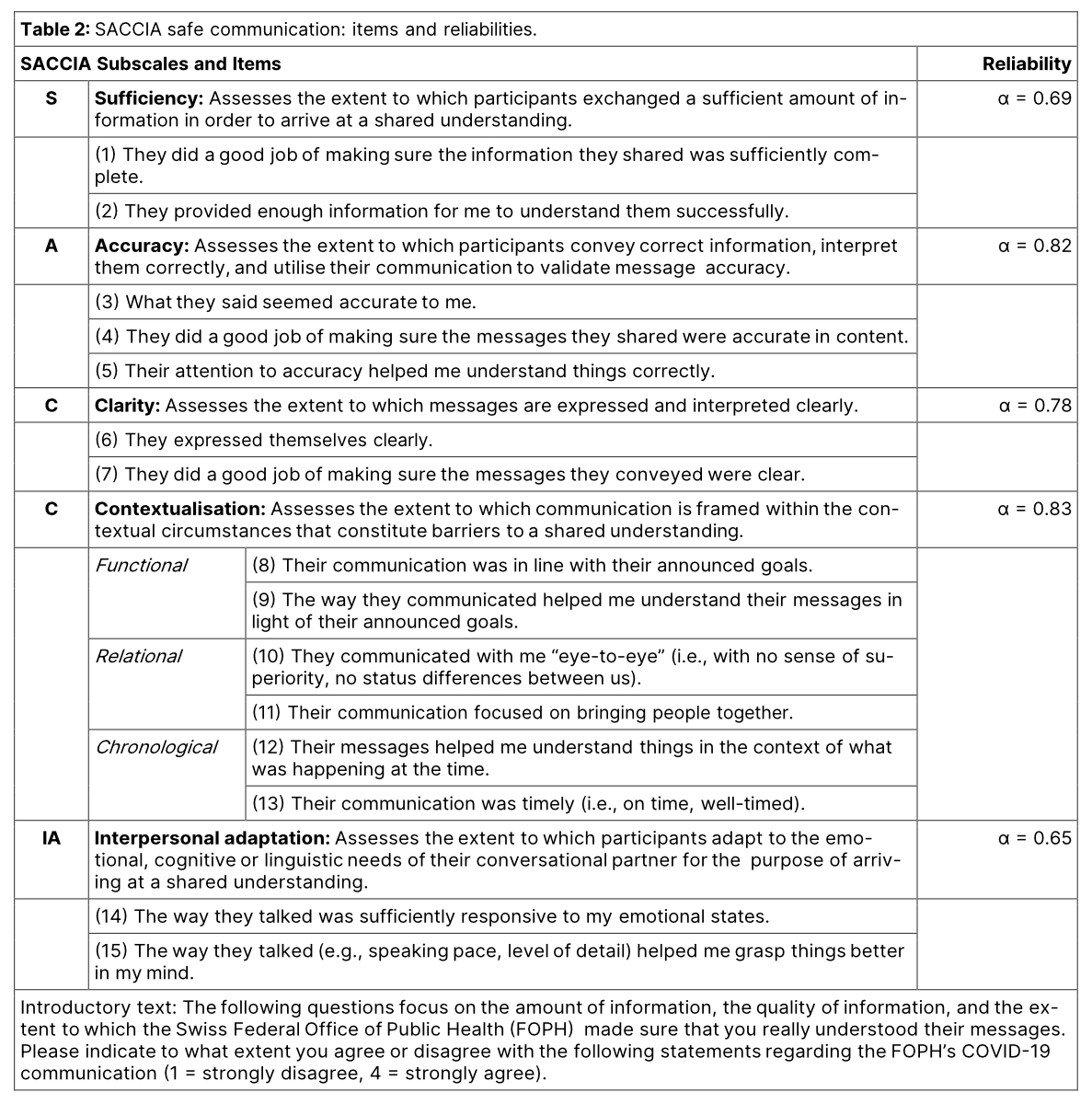

Among numerous communication measures, I used the “SACCIA safe communication” framework [11–15] for analysing the results (table 2).

The study showed that the way the FOPH communicated with the public impacted the Swiss population in critical ways. Every third respondent (38%) expressed dissatisfaction with the FOPH’s communication. Many people experienced symptoms of anxiety (34%) and depression (68%) in response to it. Numerous studies have evidenced a significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people’s mental health [16–20], and the findings of this study point at public health communication as an important source of such impact. In other words, it is not merely the fact, but rather the way in which the FOPH communicated about COVID-19 that impacted the Swiss population’s mental health.

The FOPH’s communication also severely affected people’s perceived ability to cope with the pandemic, which is an important resource for improving mental health [21]. Therefore, the COM-COVID study evidenced that safe public health communication during global crises is not a nice-to-have skill, but a serious public health matter, as it can turn people either into or away from mental health, depending on how it is conducted.

The following five lessons wrap up the key results of the COM-COVID investigation into scientifically informed “safe communication” guidelines to prepare us for similar future crises.

Lesson 1: contextualised communication serves positive pandemic outcomes

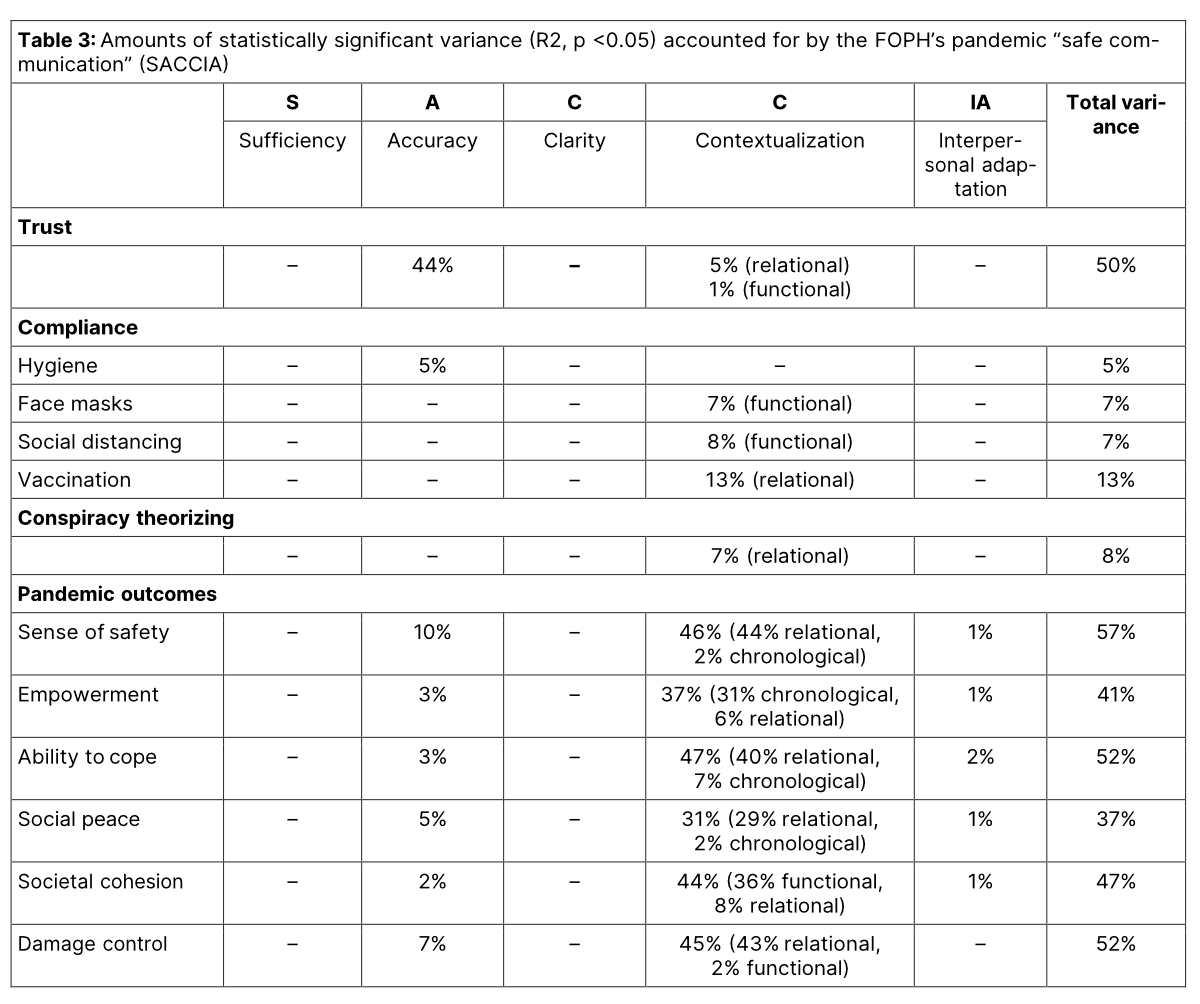

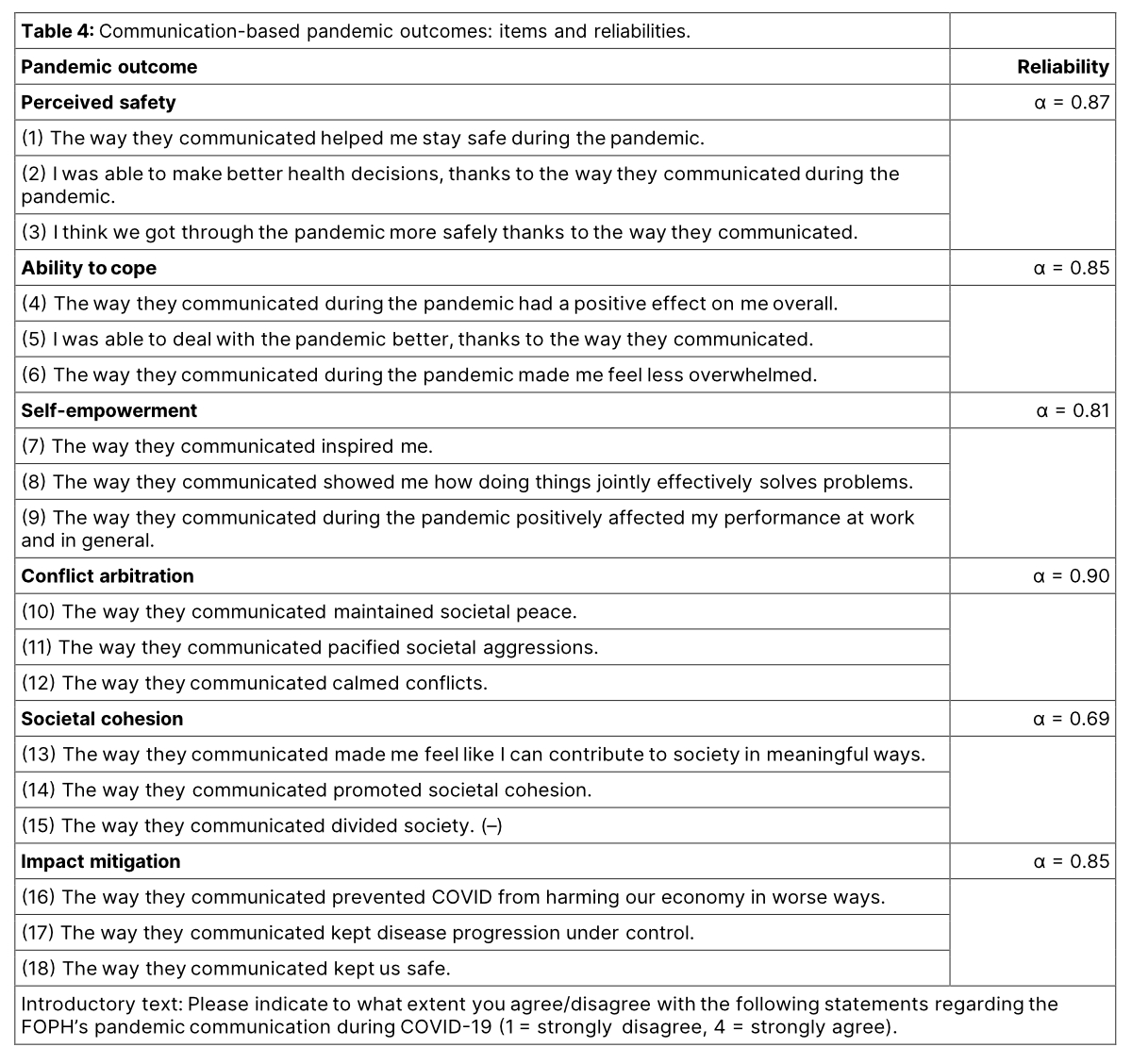

Specific “safe communication” practices stood out as particularly important in the COM-COVID study for a wide range of outcomes (table 3).

Contextualised communication, for example, in the sense of communicating in a way that comes across as a relationship-building effort, was critical for population compliance with vaccination and constituted an antidote against conspiratorial thinking. In other words, getting people to vaccinate and disengaging people from conspiracy theorising were found to be primarily a relationship-building effort. Relationally contextualised communication was also associated with a higher sense of safety, and it made people feel that the FOPH successfully maintained societal peace and mitigated worse pandemic outcomes (tables 3 and 4).

Chronologically contextualised (i.e., timely) communication was associated with an increased sense of self-empowerment in the Swiss population. This finding rhymes with existing research that has shown that timely dissemination of COVID-19-related health information from authorities increased people’s reassurance and reduced mentally disabling effects [17, 22].

Finally, functionally contextualised (i.e., goal-consistent) communication was associated with a higher sense of societal cohesion and greater compliance with wearing face masks and social distancing directives. This result is consistent with previous research that has indicated that consistent messages about required behaviours to prevent the spread of the virus, in contrast to mixed or contradictory messages, enable public understanding and elevate compliance [23].

Lesson 2: accuracy builds trust

In previous research, trust has been found to predict people’s uptake of prevention behaviours [24–28]. Conspiracy beliefs also appear to affect compliance only through levels of trust [29, 30]. Thus, trust constitutes both an opportunity and threat to public health [31]. Governmental communication can quickly swing the public from trust into distrust. Consistent with these previous findings, the COM-COVID results also speak of the importance of increasing trust through safe communication. As stated by a previous study, “without trust, there is no partnership and good communication,” and therefore trust is “essential for the path out of the COVID-19 crisis” [33].

The COM-COVID study delivered missing information as to what communication aspects are needed to establish and maintain population trust during global crises (table 3). The FOPH earned the Swiss population’s trust primarily through a form of communication that prioritised accuracy, relationship-building, and consistency with previously stated goals. Therefore, governments are well-advised to activate their communication with each other as a validation check to make sure they are conveying accurate information to the public, and to be transparent about their estimated accuracy of such information, particularly when unexpected changes arise. Failure to do so can quickly come at the expense of numerous negative outcomes, such as lower population compliance, higher conspiratorial theorising and lower public health [24–31].

Lesson 3: the truth and nothing but the truth

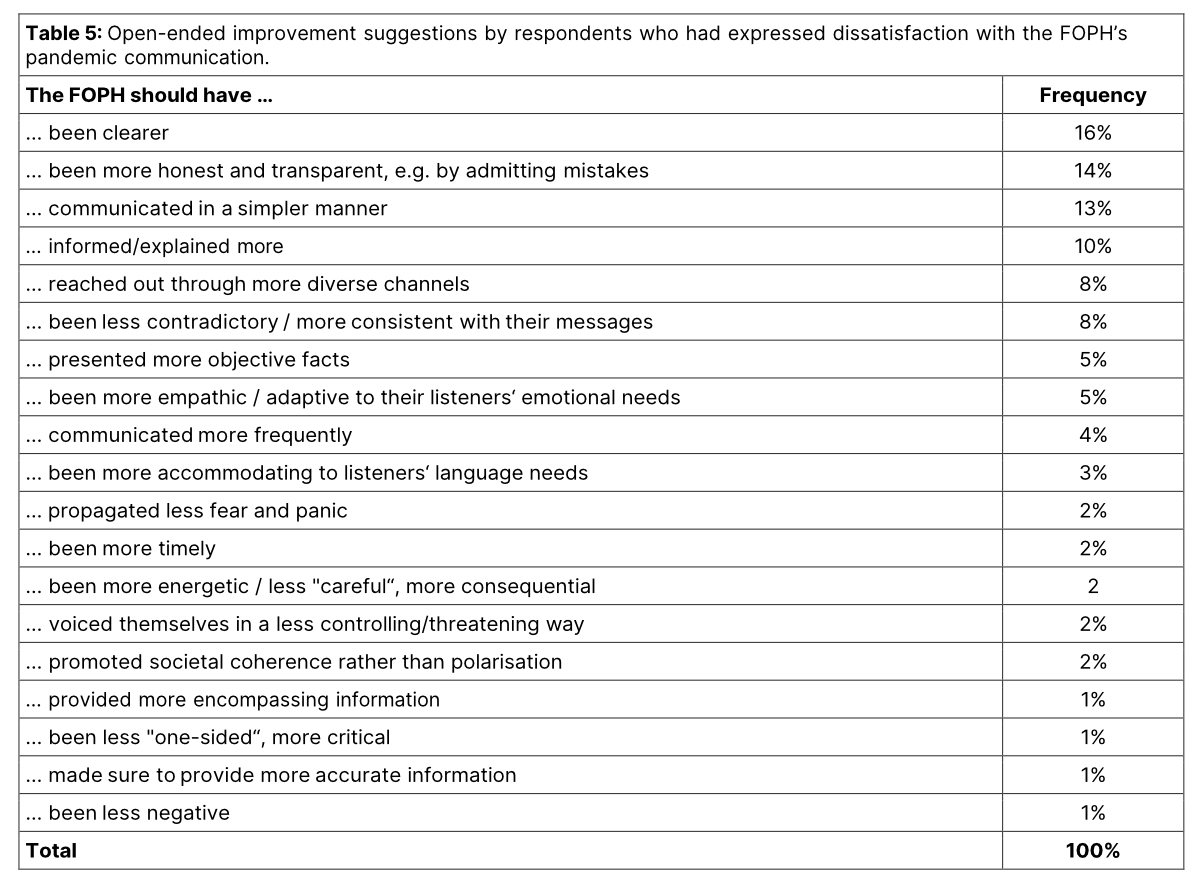

The COM-COVID data also showed that honest and transparent communication build trust in times of crisis (table 5). Respondents emphaised that earning people’s trust requires telling and standing by the truth, even if it means admitting mistakes. This finding resonates with previous studies that have found that a lack of transparency reduced trust in health authorities and facilitated the spread of conspiracy theories, limiting the government’s capabilities to maintain crisis control [34]. Indeed, prior research has even found that, while transparent communication of negative content might reduce vaccine acceptance, it still increases trust, whereas non-transparent positive communication does not increase vaccine acceptance either, but instead decreases trust and fertilises conspiracy theories [34].

Lesson 4: simplicity, clarity and understandable rationales – the “holy trinity” of success

The COM-COVID study further showed that, for the health of the Swiss population and more successful pandemic crisis management, public health offices are advised to communicate more clearly to prevent confusion (table 5). Respondents particularly desired more straightforward messages that are consistent with previously stated goals, get straight to the point and make use of visual aids for clarification, for example by showing clearly structured lists of what and what not to do, and by presenting more precise and better-structured communications. This evidence replicates previous research that has also pointed at “clarity” as an important element of effective pandemic communication, with the rationale that failing to do so contributes to the failure of containing the spread of the virus [23].

The COM-COVID study also showed that governments may benefit from simpler communication. In other words, from a form of communication that is less complicated, for example by avoiding jargon and using simpler sentence structures. Simplicity has also been suggested as a pandemic communication competence in previous studies, which have reported that the use of plain or simple language was positively associated with comprehension, recall, and message persuasion. Simpler language was also found to increase trust and public adherence to COVID-19 prevention measures in previous studies, evidencing that people tend to believe more in information that is easy for them to understand [35].

Finally, COM-COVID revealed that governments could benefit from providing more explanations, for example with respect to how the control measures protect people from infection, why changes to previous communications are made and so forth. This finding replicates previous research that has suggested that effective promotion of COVID-19 preventive behaviours requires a form of communication with the public that focuses on “not only what, but also why” [23].

Lesson 5: quality, not quantity

Among the measured SACCIA safe communication practices, “sufficiency” explained no variance in any of the measured constructs (table 3). Previous publications have hypothesised that people’s perceptions of governmental actions as “too little” or “too much” will affect their trust in the government [36]. The COM-COVID study, on the contrary, found no evidence that the quantity of communicated messages predicts any outcomes. In other words, the COM-COVID study revealed that it is not the quantity of communication, but rather the quality of communication that is critical for safeguarding public health in global crises.

Reclaiming control

Understanding how official communication can facilitate and hinder public health objectives is critical for successful crisis management. The COM-COVID study illuminated this process and gave evidence that pandemics involve much more than the spreading of a virus. COVID-19 also affected our social body, in similarly impactful ways. Like in no other situation, COVID-19 put our human communication to a test. The way we communicated affected measures of public safety and health. The next test will be: how much can we improve our communication for a safer future performance? It is yet another communication challenge for us, serving a long overdue lesson we must learn, and it may just repeat itself until we finally do. This challenge requires no rocket science or groundbreaking digital innovation. It rather requires a return to what makes us human – to what has helped our species survive, in many ways, up to this point: our highly advanced capability to communicate. The stakes are getting higher by the day. Global matters that affect entire humanity will increasingly challenge our communication skills, at levels of uncertainty that will rival with those of COVID-19. The bottom-line decisive question will be: will we reclaim control over our communication to get through these events together and grow stronger, or will we continue to allow these events to ruin what we have built up over centuries of existence? For the sake of humanity, I hope we will take this question seriously, as in the long run, only species that flock together have shown to survive.

Funding statement

The COM-COVID study was funded by the Swiss Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), Bern University of Applied Sciences (Health Division), Stefan Dräger, and Roche Diagnostics.

Prof. Annegret F. Hannawa, Ph.D., Centre for the Advancement of Healthcare Quality and Safety (CAHQS),

Faculty of Communication, Culture and Society, Università della Svizzera italiana (USI), Lugano, Switzerland

hannawaa[at]usi.ch

References

- Berger CR, Calabrese RJ. Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Hum Commun Res. 1975;1(2):99–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1975.tb00258.x.

- Gudykunst WB. Anxiety/Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory: cur- rent status. In RL Wiseman (Ed.), Intercultural communication theory (pp. 8-58). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1993.

- Berger CR. Inscrutable goals, uncertain plans, and the production of communicative action. In Berger CR, Burgoon M (eds.), Communica- tion and social influence processes (pp. 1-28). Michigan State University Press; 1995.

- Lam ME. United by the global COVID-19 pandemic: divided by our values and viral identities. Humanit Soc Sci Commun. 2021;8(1):31. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/s41599-020-00679-5.

- Traber M. Communication is inscribed in human nature. In Lee P (Ed.), Communicating peace. Penang: Southbound; 2008.

- Šrol J, Ballová Mikušková E, Čavojová V. When we are worried, what are we thinking? Anxiety, lack of control, and conspiracy beliefs amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2021 May- Jun;35(3):720–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/acp.3798.

- Hughes JP, Efstratiou A, Komer SR, Baxter LA, Vasiljevic M, Leite AC. The impact of risk perceptions and belief in conspiracy theories on COVID-19 pandemic-related behaviours. PLoS One. 2022 Feb;17(2):e0263716. http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0263716.

- Farias J, Pilati R. COVID-19 as an undesirable political issue: Conspiracy beliefs and intolerance of uncertainty predict adhesion to prevention measures. Curr Psych. 2020. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01416-0.

- Pfeffer B, Goreis A, Reichmann A, et al. Coping styles mediating the relationship between perceived chronic stress and conspiracy beliefs about COVID-19. Curr Psych. 2022. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03625-7.

- Safe Communication during COVID-19 (COM-COVID). Center for the Advancement of Healthcare Quality and Safety (CAHQS), accessed September 15, 2022, http://www.patientsafetycenter.org/ourwork

- Safe SA. Communication. Prof. Dr. Annegret Hannawa, accessed September 15, 2022, https://annegrethannawa.com/saccia-1

- Hannawa AF. SACCIA Safe Communication: five core competencies for safe and high-quality care. J Patient Saf Risk Manag. 2018;23(3):99–107. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/2516043518774445.

- Hannawa AF, Juhasz R, Wu A. New horizons in patient safety: understanding communication – case studies for physicians. Berlin/Boston: Walter deGruyter; 2017.

- Hannawa AF, Wendt A, Day L. New horizons in patient safety: safe communication – evidence-based core competencies with case studies from nursing practice. Berlin/Boston: Walter deGruyter; 2017.

- Pek JH, de Korne DF, Hannawa AF, Leong BS, Ng YY, Arulanan- dam S, et al. Dispatcher-assisted cardiopulmonary resuscitation for paediatric out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A structured evaluation of commu- nication issues using the SACCIA® safe communication typology. Resuscitation. 2019 Jun;139:144–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.resusci-tation.2019.04.009.

- Arendt F, Markiewitz A, Mestas M, Scherr S. COVID-19 pandemic, government responses, and public mental health: investigating consequences through crisis hotline calls in two countries. Soc Sci Med. 2020 Nov;265:113532. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113532.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general pop- ulation in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Mar;17(5):1729. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729.

- Alzueta E, Perrin P, Baker FC, Caffarra S, Ramos-Usuga D, Yuksel D, et al. How the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives: A study of psychological correlates across 59 countries. J Clin Psychol. 2021 Mar;77(3):556–70. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23082.

- Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, Wang Y, Jian L, Ji J, et al. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry. 2020 Jun;19(2):249–50. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1002/wps.20758.

- Torales J, Barrios I, O'Higgins M, Almirón-Santacruz J, Gonzalez-Urbi- eta I, García O, Rios-González C, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. COVID-19 infodemic and depressive symptoms: the impact of the expo- sure to news about COVID-19 on the general Paraguayan population. J Affect Disorders. 2022 Feb;298(Pt A):599-603.

- Chan AC, Piehler TF, Ho GW. Resilience and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from Minnesota and Hong Kong. J Affect Disord. 2021 Dec;295:771–80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.144.

- Xiong J, Lipsitz O, Nasri F, Lui LM, Gill H, Phan L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2020 Dec;277:55–64. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001.

- Noar SM, Austin L. (Mis)Communicating about COVID-19: insights from health and crisis communication. Health Commun. 2020 Dec;35(14):1735–9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1838093.

- McCarthy M, Murphy K, Sargeant E, Williamson H. Examining the re- lationship between conspiracy theories and COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy: a mediating role for perceived health threats, trust, and anomie? Anal Soc Issues Public Policy. 2022;22(1):106–29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/asap.12291.

- Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, Gostin LO, Larson HJ, Rabin K, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med. 2021;27(2):22–8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9.

- Larson H, Leask J, Aggett S, Sevdalis N, Thomson A. A multidisciplinary research agenda for understanding vaccine-related decisions. Vaccines (Basel). 2013 Jul;1(3):293–304. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/vaccines1030293.

- MacDonald NE; SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Vaccine hesitancy: Definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine. 2015 Aug;33(34):4161–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036.

- Latkin CA, Dayton L, Strickland JC, Colon B, Rimal R, Boodram B. An assessment of the rapid decline of trust in US sources of public information about COVID-19. J Health Commun. 2020 Oct;25(10):764–73. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2020.1865487.

- Plohl N, Musil B. Modeling compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: the critical role of trust in science. Psychol Health Med. 2021 Jan;26(1):1–12. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2020.1772988.

- Pavela Banai I, Banai B, Mikloušić I. Beliefs in COVID-19 conspiracy theories, compliance with the preventive measures, and trust in government medical officials. Curr Psychol. 2022;41(10):7448–58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01898-y.

- Jakovljevic M, Bjedov S, Mustac F, Jakovljevic I. COVID-19 infodemic and public trust from the perspective of public and global mental health. Psychiatr Danub. 2020;32(3-4):449–57. http://dx.doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2020.449.

- Newton K. Government communications, political trust and compliant social behaviour: the politics of Covid-19 in Britain. Polit Q. 2020 Jul-Sep;91(3):502–13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12901.

- Wirawan GB, Mahardani PN, Cahyani MR, Laksmi NL, Januraga PP. Conspiracy beliefs and trust as determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Bali, Indonesia: cross-sectional study. Pers Individ Dif. 2021 Oct;180:110995. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110995.

- Petersen MB, Bor A, Jørgensen F, Lindholt MF. Transparent communi- cation about negative features of COVID-19 vaccines decreases acceptance but increases trust. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021 Jul;118(29):e2024597118. http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2024597118.

- Schnepf J, Lux A, Jin Z, Formanowicz M. Left out – feelings of social exclusion incite individuals with high conspiracy mentality to reject complex scientific messages. J Lang Soc Psychol. 2021;40(5-6):627–52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0261927X211044789.

- Rieger MO, Wang M. Trust in Government Actions During the COVID-19 Crisis. Soc Indic Res. 2022;159(3):967–89. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1007/s11205-021-02772-x.